Iconic Movies That Broke The Rules Of Storytelling

The story is an important aspect of any movie, and every Hollywood screenwriter who wants to make it in the business learns the rules of storytelling. Show, don't tell. Try not to give too much exposition all at once. Follow a clear, chronological structure. These rules may seem basic, but they've provided the blueprint for moviemaking since the art form existed.

Sometimes, however, a storyteller gets a burst of inspiration that requires them to break the established rules. It could be that the effect they're going for can only be accomplished by going against audience expectations. Perhaps they're frustrated with conventional storylines and want to make a statement. Or maybe they just want to take a creative risk and see how moviegoers will react.

Not all these risks pan out, and breaking the rules can sometimes result in a confusing and unintelligible story structure. Occasionally, however, a visionary filmmaker will construct an iconic film that defies traditional storytelling and the result is something quite spectacular. Here are 12 movies that challenged what audiences thought could be done, and made their marks on cinema history.

Psycho

Based on the novel by Robert Bloch, "Psycho" shocked movie audiences when the film was released in 1960 (per The Guardian). Although some might have read the book and knew the story's twists and turns, director Alfred Hitchcock played with audience expectations by casting screen legend Janet Leigh as Marion Crane. Given Leigh's popularity at the time, most viewers were sure she'd be the film's main protagonist. However, a huge shock comes early in the film when she is stabbed to death in the iconic shower scene.

This catches the audience completely off guard, and the story shifts its focus to Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), the owner of the hotel where Marion was murdered. In the book, Norman is presented as distinctly unlikeable and a more overtly sinister character (via Medium). By contrast, the film's version of Bates is more sympathetic and surprisingly charismatic — traits that cover up his true nature and are often synonymous with psychopaths (per Forbes).

These shifts in tone keep the audience off balance, and even today modern audiences find themselves completely blindsided by the events in "Psycho." It's highly effective and is one of the many reasons why the film is still so revered today. Hitchcock took a huge risk killing off his major star so early, but it was one that ultimately paid off.

Memento

Everyone knows that conventional stories have a beginning, middle, and end, and they're usually viewed in this order. However, for the 2000 film "Memento," director and screenwriter Christopher Nolan decided to show his film in reverse order. We start at the end and see the main character Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) kill a man. From here, things move backward in time to reveal how he got to that moment.

It is a gripping film noir-style mystery that absolutely benefits from being told end-to-beginning. Leonard suffers from amnesia that prevents him from making new memories. This causes him to lose his memory of recent events every few minutes, leaving him regularly disorientated. By telling his story in reverse order, audiences experience his confusion alongside him as he searches for the man who killed his wife.

Nolan's masterful use of non-linear storytelling has inspired much of his later filmography. The director frequently plays with mind-bending concepts in films like "Inception," "Interstellar," and "Tenet" (via Complex), giving audiences more incentive to pay close attention to his movies' intricate plots.

Forrest Gump

Exposition is a tricky thing to manage in storytelling. On the one hand, you need your audience to have enough crucial information in order to root for the characters and feel invested in the narrative. On the other hand, dumping too much exposition all at once can be considered lazy storytelling, as it doesn't give the audience the chance to work things out for themselves.

However, when the film itself is all about storytelling — and is being told by Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks) — excessive amounts of exposition prove to be a necessity. Forrest is a simple man whose obliviousness to social norms sees him sharing his life story with anyone and everyone while he waits for the bus. Bullied for his low intelligence, yet guided by unshakeable decency, Forrest wanders through three decades of American history. Along the way, he becomes a football star, a war hero, and a millionaire tycoon, all while inadvertently influencing multiple historical events.

Initially put off by Forrest's tendency to overshare, the bus passengers gradually become riveted to his tale. Movie audiences also found themselves charmed by his storytelling, and "Forrest Gump" received multiple Oscars — including best picture — at the 67th Academy Awards. The film is an undeniably odd look at American history, but also one that's compulsively watchable.

Frozen

Disney has a tried and tested formula that has worked for decades — particularly in their princess movies — however, "Frozen" is one that defies the rules. Up to this point, audiences accepted that the girl would get the guy, and Prince Charming would always be on hand to save the day with a true love's kiss. Not only does "Frozen" do away with this formula, but at times it actively ridicules it.

To begin with, Princess Anna (Kristen Bell) is the typical Disney princess — she longs to meet the one and be swept off her feet. At the same time, she wishes for the closeness that she had with her sister Elsa (Idina Menzel) when they were children. This leaves Anna lonely and vulnerable, and causes her to immediately fall for the first eligible bachelor she meets — Prince Hans (Santino Fontana) — something that Elsa dismisses telling her, "You can't marry a man you just met."

In any other Disney film, you'd think wedding bells would be on the cards, but "Frozen" takes a very different turn. After Elsa's ice powers are revealed, she retreats into the mountains and Anna tries to bring her home. This forces Anna to focus on rekindling the sisterly bond she has with Elsa, and ultimately it is the love between the two siblings that saves the day. The film's emphasis on non-romantic love and its self-awareness of overused Disney tropes proves refreshing, and it shows that sometimes you don't need the Prince to save the day, you just need your sister.

Casablanca

It's a classic story: Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, and then boy spends the rest of the story winning the girl back and earning their happy ending. Romantic movies have been following this formula for generations, and audiences never seem to get tired of it.

This is why 1942's "Casablanca" stands out as such an anomaly. Set during the early days of World War II, we're initially led to believe we're seeing a typical love story when Casablanca nightclub owner Rick (Humphrey Bogart) re-encounters his old flame Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman). Through flashbacks, we learn Rick and Ilsa fell in love in Paris, but she left him when she learned her husband — Czech Resistance leader Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) — was alive after escaping a concentration camp. At first cynical, Rick sympathizes with Ilsa after she confesses that she still loves him. He helps her husband leave German-occupied Casablanca, and it looks like Rick and Ilsa will get their happy ending.

At the last moment, however, Rick insists Ilsa leave with Victor, acknowledging that the two need each other more and that Ilsa will regret not going with her husband. While this denies the love story it's expected happy ending, it also provides Rick with a satisfying character arc as he goes from cynic to active war resistor. Giving up the woman you love might not be the way most romantic movies leave an audience, but in the case of "Casablanca," it offers one of cinema's most memorable endings.

Reservoir Dogs

Heist films typically show a group of criminals planning a robbery for the first half of the film and then committing the crime during the climax. Complications inevitably ensue, creating drama as the crew tries to pull off the heist. In the case of Quentin Tarantino's "Reservoir Dogs," however, both the planning and execution of the heist are glossed over, and the audience spends the majority of the movie watching the team deal with the aftermath of a botched jewelry heist. While this would normally leave audiences feeling cheated out of the best parts of a heist film, Tarantino still manages to fill it with plenty of tension.

None of the gangsters know each other and go by code names like Mr. Blonde, Mr. Orange, and Mr. Pink. This makes their actions and agendas unpredictable, as we discover when Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen) turns out to be a psychopath who sadistically tortures and kills a captured policeman. Meanwhile, Mr. Orange (Tim Roth) turns out to be an undercover police officer who was shot during the heist. None of the other crooks know this, however, leading them to turn on each other as they attempt to find the traitor amongst them.

All this creates a riveting series of events that leaves the audience constantly on edge as they attempt to piece together each man's true identity through flashback scenes and dialogue cues. The result is one of Tarantino's most tense and well-loved movies. Not bad for a heist film that doesn't show the heist.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Although regarded today as one of the British comedy group Monty Python's best films — not to mention one of the funniest comedies ever — "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" defies description upon initial viewings. Seemingly a comic retelling of the legend of King Arthur and his knights of the round table, the film sees the knights galloping horse-less across Britain, battling the man-killing Rabbit of Caerbannog, and escaping an animated cave monster after the animator suffers a sudden fatal heart attack. At the end of the film, a modern-day police squad appears to arrest King Arthur and break the movie camera — and the fourth wall — causing the movie to abruptly end.

Inane, random, and utterly bizarre, "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" nonetheless connected with many viewers who appreciated its wacky, irreverent sense of humor. The film was later adapted into the equally silly — and successful — musical "Spamalot" in 2005. Throughout their sketch series and movies, Monty Python proved time and again that there is a place for subversive comedy and irreverence, and taught audiences to always expect the unexpected.

Titanic

There are plenty of reasons why James Cameron's 1997 historical romance about the doomed ocean liner shouldn't work. For one thing, the story takes place on the water, making it notoriously difficult to shoot (per Empire). The audience all knew the Titanic would sink at the end so there's little chance of a surprise. And finally, the dramatic conclusion leaves little opening for a sequel — even though an ill-advised 2010 follow-up tried to prove otherwise. However, "Titanic" not only proved a hit with audiences but went on to become one of the highest-grossing films of all time and a winner of multiple Academy Awards, including best picture.

For his film, Cameron chose to put the film's historical elements in the background, focusing instead on a fictional love story between society girl Rose (Kate Winslet) and the penniless but virtuous vagabond Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio). This allowed the film to deal with universal themes like class struggles and love, and made it more like a retelling of "Romeo and Juliet," with that story's elements of tragedy intact. Meanwhile, the ship's impending doom offered a countdown that added to the dramatic tension, keeping audiences engrossed for the film's 195-minute runtime. Add in Cameron's expertise at crafting epic action scenes, a stirring score by James Horner, and Celine Dion's breakaway pop hit "My Heart Will Go On," and it almost seems inevitable that "Titanic" would become a cultural phenomenon.

Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino has regularly stated he will only make ten films before retiring as a director (per Independent). With many of his films using innovative storytelling techniques, it could be that the director is trying to cover all bases before he hangs up the camera for good. For "Pulp Fiction," Tarantino offered his take on dark crime thrillers by focusing on dialogue more than action.

Most movies try not to overload their stories with too much talking. Films are a visual medium, after all, and most viewers go to these sorts of movies for fight scenes, not lengthy monologues. Yet while Tarantino includes plenty of violence in his pulp novel-influenced story, it's the dialogue that makes the scenes particularly riveting. Few screenwriters would choose to use a conversation about cheeseburgers in an intimidation scene, but the sequence — which sees hitmen Jules (Samuel J. Jackson) and Vincent (John Travolta) invade the apartment of three young men and appropriate their breakfast before shooting them — stands out as one of the film's most unnerving scenes.

Tarantino's tendency to fill his film with dialogue also makes "Pulp Fiction" very quotable, and almost 30 years after its release, its script is still hugely influential (via The Take). Not all screenwriters can produce such memorable lines, but Tarantino seems to do this on a regular basis.

Adaptation

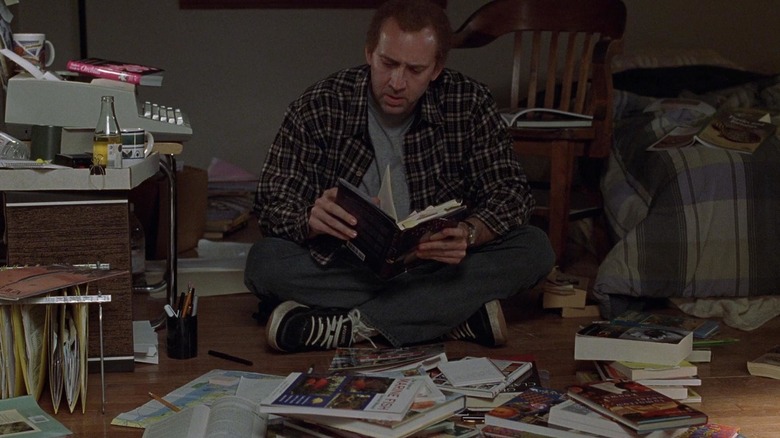

Metafiction has become increasingly popular, with mainstream movies like "Deadpool" making frequent use of tropes like fourth wall breaks and self-referential humor. However, Spike Jonze's 2002 meta-comedy drama "Adaptation" takes metafictional narratives to new extremes. It follows screenwriter Charlie Kaufman as he struggles to adapt Susan Orlean's novel "The Orchid Thief" into a usable screenplay and deal with his anxiety, depression, and social phobia.

Kaufman — and his fictional twin brother Donald — are both portrayed by Nicolas Cage. However, Charlie Kaufman is also a real-life screenwriter who wrote the script for "Adaptation," basing it on his own unsuccessful attempts to adapt Orlean's novel for Hollywood. Thus, "Adaptation" is essentially the fictional story of Kaufman's failure. The screenwriter even admitted he wrote it without pitching it to anyone since he was sure it wouldn't have been approved (per Variety).

Yet not only was "Adaptation" made, but it won multiple accolades, including a BAFTA for best adapted screenplay. Audiences found the movie's unexpected angle not only original and funny but also thought-provoking. It might seem like a ridiculous premise, but clearly, the unique exploration of failure in "Adaptation" struck a chord.

Night of the Living Dead

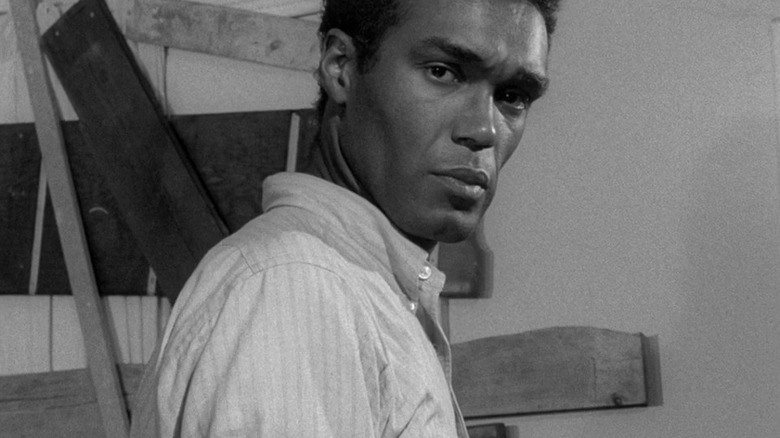

George A. Romero's 1968 independent horror film "Night of the Living Dead" continues to scare audiences today (per The Guardian), but when it was first released, the movie was notable for more than just its frightening elements. At the time, casting a Black stage actor like Duane Jones as the film's lead, Ben, was controversial. Jones also portrays Ben as a cool-headed leader who keeps a houseful of hysterical people alive when the dead rise from the graves and attack the living.

At the time of its premiere, the MPAA film rating system wasn't in place yet, so many young children came to see the movie and were horrified by scenes of "ghouls" — notably not referred to as zombies — eating their victims. After surviving the ghouls, the film ends on a shocking and surprising note with Ben killed by an armed posse who mistakes him for one of the creatures.

Variety notoriously called the film an "orgy of sadism" and "pornography of violence," but nevertheless, the film grossed millions, thanks to audiences who were intrigued and horrified by the gruesome images (per Forbes). Some film historians consider the film a critique of '60s American racism and politics (via The Village Voice), although Romero denies he cast Duane Jones specifically for his race, citing his acting talent instead (via The Wrap). Nevertheless, with prominent Black leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. assassinated only months before the film was released, it's easy to see how audiences could draw those connections.

Princess Mononoke

Almost all of Hayao Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli films have elements that challenge audiences and go against the expectations of animated films. Yet 1997's "Princess Mononoke" stands out due to its surprisingly gory imagery, and the way it uses this to showcase its themes of environmentalism.

Early in the film, a prince named Ashitaka (Yōji Matsuda) is cursed by a demon and contracts an infection that mutates his arm. He uses the superhuman strength the curse provides to battle soldiers — often by decapitating or impaling them with his arrows. The mystical Great Forest Spirit is also decapitated by the humans at one point, and the woman who takes his head gets her arm bitten off by a giant wolf god later on.

Unlike many animated fairy tales, there are no clear-cut villains in "Princess Mononoke" — only humans and forest spirits who find themselves in conflict with each other. The heroes, Ashitaka and San (Yuriko Ishida) — a woman raised by wolves — find themselves in between the conflict and must convince everyone to stop fighting for everyone to survive. It's a complex story with beautiful yet disturbing imagery that doesn't offer the clean-cut happy ending of a Disney-style fairy tale. Yet this uniqueness may be what made it so appealing to audiences across the world.