Yellowstone Should End Soon, Actually (And Here's Why)

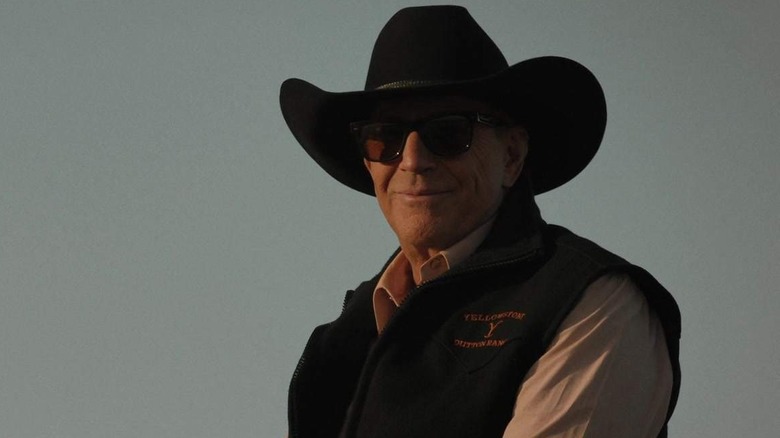

All hell broke loose on February 6 when Deadline reported that the record-breaking force that is Taylor Sheridan's "Yellowstone" was nearing its end, thanks in large part to its lead star, Kevin Costner (aka, the series' central patriarch and protagonist, John Dutton). Evidently, sources told the publication that disputes over Costner's schedule and the actor's desire to focus on his own projects have led to morale issues with the series' other stars, and created frustration for Sheridan. After rejecting Costner's recent time commitment proposal, these sources claimed, the network decided to shift its focus to a new series potentially led by none other than Matthew McConaughey.

In response, the network sought to quell fans fears: "We have no news to report," said a spokesperson for Paramount Network, adding "Kevin Costner is a big part of 'Yellowstone' and we hope that's the case for a long time to come." Though the spokesperson didn't officially confirm McConaughey's casting in any upcoming series, they did reference the franchise expansion and say, "Matthew McConaughey is a phenomenal talent with whom we'd love to partner" (via Entertainment Weekly).

Now, maybe it's just smoke, or maybe it's a big old "Yellowstone" bonfire, but whether you're a die-hard fan of the series, a serious series skeptic, or one of the many who tune-in because you simply can't look away (even if you aren't quite sure how to feel about the drama unfolding before you), it may be time to come together around a cold, hard truth: "Yellowstone" should end soon.

No, Yellowstone isn't too big to fail

If we've learned anything from the sprawling film and television universes populating our landscape today, it's that they can really only go one of two ways. They can either continually re-invent themselves, evolving to fit the needs, concerns, and cultures of each new generation while keeping an eye on the timeless ethos and stories that made them relevant in the first place (see: "Star Trek"), or, they can over-saturate a specific moment in time, cling desperately to their flagship series well after it has already taken on water, and subsequently force that series to devolve into a soggy, sinking, abandoned ghost ship (see: "The Walking Dead").

Like it or not, the "Yellowstone" universe is just as prone to this phenomenon as any other epic. And continuing to tether the entire world to a story that's gone on too long prevents those spin-offs from successfully .... well, spinning-off. But the more immediate argument for bringing "Yellowstone" to its natural conclusion has less to do with expansion (a point to which we'll return) and more to do with human nature: as "Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks" once sang, "How can I miss ['Yellowstone'] if you won't go away?"

If nothing gold can stay, it stands to reason that once something does stay, it's no longer gold. To drag "Yellowstone" out across seven or eight seasons (or, John forbid, nine or ten) would be to forget that transience is a necessary component of appreciation — an ironic breed of amnesia for storytellers, considering just how integral "the finite" is to creating a compelling narrative. Narrative tension requires stakes, and the longer the Duttons manage to survive their increasingly dramatic near demises, the less credible those stakes become.

Yellowstone sealed its fate early on

"Yellowstone" has never apologized for being the melodramatic western soap opera that it is. But suspension of disbelief notwithstanding, when you've either blown up, or nearly shot, or beaten to death ... well, every single one of your central characters by the end of Season 3, you've pretty much cemented yourself as a six-season series at most. "Yellowstone" started off at 10, and cranked things up to 11 pretty immediately. But in order to hang out at this decibel and not devolve into unbridled chaos (as opposed to the Duttons' usual, more bridled chaos), a series needs one of two things that "Yellowstone" doesn't possess: an episodic structure (see: everything Dick Wolf), or, a sprawling geographical or narrative universe that can introduce new landscapes and characters to further complicate and flesh-out the story (see: "Game of Thrones," or, "Vikings").

"Yellowstone" has sought to solve this problem by expanding its universe chronologically or geographically in spin-offs, but this doesn't change the main series' limitations. Couple this with an extraordinarily simplistic premise (a single family fights to keep its ranch, which we rarely leave) and you end up with a pretty specific shelf life — one that should already concern the more food-safety conscious among us.

Partway through Season 2, "Yellowstone" made a decision — one that would not only lock-in its viewership and alter the discourse surrounding it for every season to come, but limit the trajectory of the story as a whole.

For a show about a cattle ranch, Yellowstone's been stingy with the meat

For the first season-and-a-half (give or take a few episodes) of "Yellowstone," Sheridan stood by his intent to, as he told The Atlantic "[Shatter] the myth of the American Western." There was nuance, a variety of perspectives, and an attempt to thoroughly investigate and depict the ongoing consequences — and subvert the toxic mythology of — the so-called "winning" of The American West. However one feels about how successfully the series pulled these things off, there was a clear distinction between the series' intentions and ethos and those of the Dutton family. For whatever reason (ratings and the politics of the "Yellowstone" fandom, most likely), the prioritization of these themes fell away early on, and by Season 3, the Duttons' desires became the series' desires. Whether you loved or hated that shift, the reality is it makes for fairly redundant storytelling. There's only so many times Hero X can fight Shiny New (or Ongoing) Opponent Y for the same prize, to promote the same thesis, in the same location, before things start to curdle, and the story turns to cheese.

Consider, if you will, the B-roll from a Marlboro commercial that was most of "Yellowstone" Season 4. Audiences love the bunkhouse, but in what way, exactly, did all those various fist fights and sub-plots move the overarching story forward, or even flesh out its landscape? When a bunkhouse beef between side characters is the most called-upon through-line over the course of several episodes, you've officially crossed into the land of filler. As for the few new characters or stories we've seen in Seasons 4 and (thus far) 5, they've only served to further inhibit the narrative's ability to grow or surprise us.

Beth and Jamie have taken over Yellowstone, and the consequences are clear

If "Yellowstone" Season 5 had an honest tagline, it would probably be: "Come for views, stay for caricatures."

So far, the season has mostly comprised of Duttons waxing poetic about their worldview. Occasionally, we're treated to characters with differing stances, but they really only exist as sounding boards. These characters are either instantaneously won over by John Dutton (which is pretty easy when they start off as cartoonish, naive caricatures, like Piper Perabo's Summer), or, they're depicted as one-note stereotypes (like Dawn Olivieri's Femme Fatal Sarah, who at least has a mind of her own).

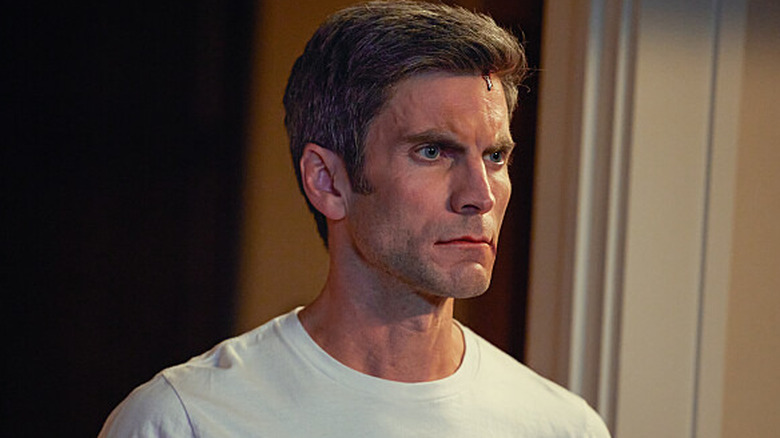

Season 5, Episode 8 finally did throw some storylines at us — e.g., Jamie (Wes Bentley), and Beth (Kelly Reilly) potentially attempting to murder the other. But frankly, that option has always been there, particularly for Beth. What's more, the outcome here is obvious given the set-up: Jamie has a baby and needs narrative redemption, while Beth wants a baby and needs narrative saving: want to place bets that Jamie dies valiantly (or horribly) and Beth adopts his baby?

And then what? By now, 80% of Beth's story is hating Jamie, and 98% percent of Jamie's story is being scared of Beth. If one of them dies, show's over. If they make up, show's over. Had something like this happened in, say, Season 2, the series could have recovered. But it's been relying on these two for so long that their resolution just has to be the series resolution, for any of this long-form storytelling to feel satisfying in the end. "Yellowstone" must decide whether to be The One that Got Away or The One That Hung Around Too Long, particularly as the spin-offs keep coming.

Yellowstone is an overbearing parent series

Sheridan excels at enveloping the viewer in a specific time and place, and using the actual history of that time and place to dictate his characters and character-driven stories. Combine that skill with the writer-director's penchant for sweeping, cinematic landscapes typically associated with a bygone era in film — or with folk horror, which Sheridan really should consider getting into — and it all translates to one thing: an artist who's tailer-made (no, we're not apologizing) for period pieces. Both "1886" and "1923" have far surpassed "Yellowstone" in terms of emotional and thematic resonance, thanks in large part to the fact that their melodrama doesn't feel like melodrama — it feels authentic. And it feels that way not in spite of its distance from the modern day, but because of it. Like fantasy films and series, period pieces allow us to embrace certain plot points and bits of dialogue and drama that, in contemporary narratives, feel anachronistic or over the top.

There's just one thing holding these expansions back, and that's "Yellowstone." Like a too-involved parent, the flagship series keeps popping up in their narratives in cringe-worthy ways. Having John Dutton's ancestors experience, shot for shot (sometimes quite literally), the exact same things John and his family members will experience in the flagship series ends up pushing the story into the supernatural. Did a wood witch put a curse on this family at some point in the old country, and doom them to forever survive or die from identical attacks? (Wait, maybe Sheridan's already doing folk horror ...)

Even without these overly contrived winks, the universe would still have the problem of being tethered to a sinking center — one whose very popularity is causing problems for Paramount Network as it is.

ViacomCBS can finish Yellowstone one of two ways

Like John Dutton, "Yellowstone" is a relic of the past, in that it was created before Paramount(ViacomCBS) had a streaming service of its own. The show's popularity is a thorn in ViacomCBS' side, namely because as demand for streaming "Yellowstone" increases, more money goes into Peacock's pocket (the service that actually owns the streaming rights), and that means less money for ViacomCBS (per CBR).

Here's the thing about entertainment conglomerates: they really, really like making money. A series that costs as much as "Yellowstone," but that isn't making the money it could be making for the network that birthed it, has little chance of lasting past a sixth season when its spin-offs could prove much better cash cows.

Put bluntly, even if "Yellowstone" didn't have a star ready to move on, ViacomCBS would already be looking to shift focus to spin-offs which they can actually host on Paramount+. And to move on without first resolving the series that started it all — to let it limp along indefinitely without receiving the creative and financial focus it needs to survive, while refusing to put it out of its misery — well, that would be cruel.

Capitalism notwithstanding, for those who really just don't want to say goodbye, consider this: while the over-the-top nature of "Yellowstone" was unarguably part of its initial appeal, there's only so far it can go before it crosses over into the unintentionally comedic. Sheridan knows that. What's next? Beth single-handedly fights off an entire pack of wolves while smoking a cigarette, acquiring and liquidating Goldman Sachs on her cell, stomping on Jamie's head, and carrying a near-death Rip on her back? If that sounds ridiculous to you, friends, then maybe you don't want "Yellowstone" to go on much longer, either.