Women Talking's Entire Journey From Novel To Big Screen Adaptation

This article discusses depictions of sexual abuse. If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

In one of the many evocative lines in "Women Talking," it's noted that the primary characters couldn't even comprehend their trauma and pain over the sexual abuse they've experienced because they haven't had the language or framework to communicate it. Growing up in a Mennonite colony, the women at the heart of "Women Talking" have been relentlessly abused and have only recently, as the film begins, realized that mortal men in their own community were responsible for tormenting them. To confront unspeakable horrors, you must give them a name. To talk about something is to rob it of some of its power. Writer-director Sarah Polley's feature film "Women Talking" and its source material of the same name by Miriam Towes confront the horrors of surviving sexual abuse and stifling societal conditions by creating a story where women can openly talk about their varying experiences and perspectives.

It's a heavy story, but also one as deeply moving as it is beautifully crafted. As if it weren't enough for "Women Talking" to be a great movie, it's also produced many great stories of how it made its way from bookshelves to movie theaters. The saga of its creation, from Sarah Polley's passion to the deep bond formed by the cast, speaks volumes to how much care went into a film that provides a framework for comprehending one's own past and conceiving of one's own future.

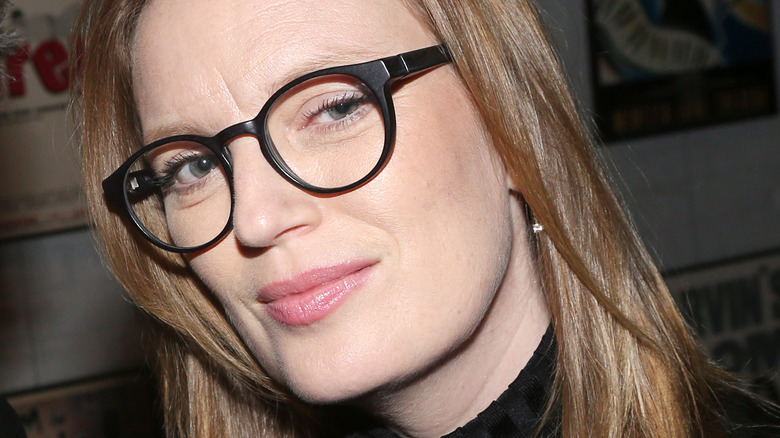

Women Talking brings Sarah Polley back from a long absence

After the 2012 release of Sarah Polley's documentary "Stories We Tell," a decade would pass without a follow-up feature. Polley largely stayed out of the limelight until returning as a filmmaker in 2022 with "Women Talking." Part of why she stayed away from directing for so long was because of an injury she sustained in 2015. As explained by The New Yorker, Polley experienced a concussion that impacted her for years and caused her to leave a project she was supposed to direct. As the filmmaker explained to IndieWire, both that injury and her dedication to her three children impacted her desire to take on any new projects. Filmmaking is a time-consuming process, and one that Polley didn't feel was more important than spending time with her family.

The combination of all these personal factors makes it apparent why Polley would've taken some time off as a director. But she explained to Toronto Life that when she got ahold of the book "Women Talking," it proved to be such an urgently important text (not to mention that her concussion-related injuries had grown more manageable over the years) that she decided to plunge into directing again. While it's exciting to see Polley lured back to filmmaking, it's also entirely understandable why she was gone for so long.

A new scale of filmmaking for Sarah Polley

While "Women Talking" isn't Sarah Polley's first directorial effort, it's a departure from her earlier works in terms of scale. Polley's initial films like "Take This Waltz" were anchored by recognizable actors, but were much smaller in focus and made independently of major studios. By contrast, "Women Talking" was financed and produced by MGM's Orion Pictures division, featuring a much bigger cast and more elaborate sets than her earlier work. Polley was going to be exploring a lot of new ground as an artist by taking on "Women Talking," and the prospect of exploring a grander canvas of storytelling was an exciting one.

Polley explained to The New Yorker that her experiences grappling with the aftermath of her concussion had made her much more open to seemingly daunting tasks than she had been earlier in her life. After all, if she could survive that medical emergency, what couldn't she do? Thus, Polley leaped at the opportunity to make a bigger movie than she ever had before, especially since she was cognizant that MGM offering up a notable budget for such a challenging feature was a remarkable occurrence. Rather than be petrified by the unfamiliar, Polley was enchanted by the challenge of taking on her most expansive movie ever with "Women Talking."

What attracted Sarah Polley to Women Talking

Even before she directed "Women Talking," Sarah Polley waws clearly open to directing movies based on pre-existing source material. For instance, her 2006 film "Away from Her" was an adaptation of Alice Munro's text "The Bear Came Over the Mountain." Where the filmmaker does get picky is in what kind of material she's interested in working with. Polley explained to Entertainment Weekly that what made the original "Women Talking" book by Miriam Toews so compelling to her was that it grappled with such weighty ideas in a manner that felt unprecedented to her. After reading it, she was left contemplating big concepts rather than having the book deliver any definitive answers to its own questions, which solidified in Polley's mind that Toews had written something extraordinary.

Polley was also entranced by Toew's depiction of democracy in action, specifically how it can manifest in matters far beyond electoral politics. The challenge of translating these concepts and the book's characters into a cinematic form kept stirring up Polley's imagination. Additionally, the director noted to IndieWire that she was compelled to adapt "Women Talking" so that she could create a movie for her children that could offer some guidance on how to improve a deeply flawed world. Weighty ideas and ambitions informed Polley's decision to adapt "Women Talking" into a motion picture, and they resulted in an equally towering work of cinema.

What Claire Foy loved about director Sarah Polley

Though she hasn't been appearing in movies long, Claire Foy has already worked with several incredible directors, including Steven Soderbergh and Damien Chazelle. With the role of Salome in "Women Talking," Foy can add Sarah Polley to her list of collaborators. The actress happily detailed to Moviefone that her experiences working under Polley's direction were nothing but positive. What especially stood out to Foy about Polley's filmmaking process was how inclusive it was. Rather than cutting herself off from everybody on the set in pursuit of her own vision, Polley openly encouraged everybody in the production to contribute their ideas. Opinions from any member of the cast or crew were applauded rather than drowned out.

Foy also felt that Polley did a great job setting an example of being a leader, the kind of diligent figure more filmmakers should be. Foy's comments about Polley paint a picture of the "Women Talking" director as very down-to-earth, while remaining boldly creative. Striking up that kind of personality ensured that Polley secured Foy's loyalty and artistic conviction. Even in a career that's found her working with so many famous names, Sarah Polley's unique style clearly struck a deep chord with Claire Foy.

What informed the casting process of Women Talking

"Women Talking" is an incredibly intimate affair leaning heavily on dialogue. Because of the priorities of the story, it was always going to be incredibly important to cast exactly the right actors. If the casting didn't click for "Women Talking," then the dialogue was going to ring hollow and the whole enterprise would sink. Casting director John Buchan explained to The Wrap that he dedicated six months to breaking down potential actors for each of the main roles, and that there was an emphasis on exploring individuals who had a lot of experience performing on stage. In those confines, performers get comfortable with handling lots of dialogue in long, intimate takes — a skill that would serve "Women Talking" cast members extremely well.

Polley further noted that casting "Women Talking" was also complicated by the fact that several characters are blood relatives of one another. This meant finding performers that not only fit their specific role, but could also be believable as family. This specific obstacle proved daunting to some of the actors. Judith Ivey, for instance, had to contend with playing the mother to modern silver screen legends like Rooney Mara and Claire Foy. Even with so many challenges, though, the casting process for "Women Talking" eventually yielded an outstanding cast who expertly handled all the finer nuances of such a harrowing narrative.

What inspired the look of Women Talking

Sarah Polley's directorial efforts have each incorporated a very distinctive and unique look — you really never know what you're going to get from her filmmaking exploits. Her 2012 documentary "Stories We Tell," for instance, employs a more realistic aesthetic stemming from the heavy use of vintage home video footage, while her 2011 motion picture "Take This Waltz" is peppered with vibrant colors evoking the production design of a Pedro Almodovar movie. For "Women Talking," Polley once again takes a unique visual direction, making the feature look unlike anything else in her filmography.

Polley explained to Entertainment Weekly that, unlike "Stories We Tell," "Women Talking" couldn't have a look that was rooted entirely in reality. Because Polley viewed the story more as a fable, with characters existing in a world rooted in a particular vision of the past, the director wanted a look that evoked yesteryear. Original plans to shoot the feature in black-and-white were scrapped once this approach lent the entire movie too grim a look. Instead, Polley and the crew embraced a muted color palette and constantly fiddled with the saturation of the images on-screen. These details nicely reinforced key elements of the themes of "Women Talking" and underscored Polley's visually audacious tendencies as an artist.

Ben Whishaw was honored to be in Women Talking

To absolutely nobody's surprise considering his terrific work in earlier movies like "Cloud Atlas" and "I'm Not There," Ben Whishaw delivers outstanding work in "Women Talking" as August, the schoolteacher tasked with recording the minutes of the discussions between the primary female characters. August is the most prominent man in the story of "Women Talking," and the only male who's even seen on screen for extended stretches of time, yet there's so much more to the character than this detail. His relationship with his now-deceased mom or his quiet pining for Ona (Rooney Mara) further add to the compelling nature of this figure, and Whishaw handles these nuances with finesse.

Whishaw explained to The Playlist that, even before he got to those specific details about August as a character, he was intrigued by "Women Talking" as soon as he received the script and saw it was a Sarah Polley screenplay adaptation of a Miriam Toews book. The actor also felt honored to be in a film where he could turn over the spotlight to a bevy of talented performers like Jessie Buckley and Rooney Mara. Realizing that this wasn't a movie about him just made Whishaw all the more grateful to be a part of such a special project. With this kind of thought process, it's no surprise that he adds another unforgettable performance to his stacked filmography with "Women Talking."

The accuracy of the Mennonite costumes

Costume designer Quita Alfred's personal history ended up heavily impacting her work on "Women Talking." Alfred explained to Variety that she grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which has a large Mennonite community. Having been around and adjacent to this world for so much of her life, Alfred knew she was uniquely qualified to work on the outfits for this production. Specifically, Alfred traveled to a Mennonite community and purchased fabrics and other items sold by its residents. The costumes in "Women Talking" are crafted from those very materials, used by actual members of Mennonite colonies.

In putting together the outfits themselves, Alfred and her costume team further drew from reality in hewing closely to styles informed by the ancestral history of many Mennonite communities. Floral prints came from history tied into Poland, for instance, while territories like Ukraine and Russia informed the kind of colors used in prayer covers. Mennonites are rooted in countries all over the planet, and being aware of that history helped to lend a sense of variety to the outfits seen in "Women Talking." With anyone else on costume duties, the film may have been deprived of so much rich authenticity.

Epic cinematography for an intimate film

On paper, the constrained scope of "Woman Talking" wouldn't seem to lend itself to cinematography that one would describe as "epic." But it's easy to forget about the minimal number of locations as one watches the film and gets so swept up in the performances, emotions, and themes. Cinematographer Luc Montpellier noted to Gold Derby that he was well aware of the weight of the script, and that informed his decision to give the feature a look as impactful as the concepts the central characters are grappling with.

This was especially apparent in the choice to frame "Women Talking" in a 2.76:1 aspect ratio, which lent each frame an especially wide look. Montpellier felt this detail allowed "Women Talking" to evoke the appearance of classic epics while making room for perspectives and thoughts that could've never been expressed in those vintage features. Even with these grandiose tendencies, Montpellier was very careful not to let the grand frame overwhelm the intimate performances driving the entire movie. In fact, the cinematographer would often let the choices of actors like Jessie Buckley and Rooney Mara dictate what his camera did, rather than bending the performers to the movements of the camera. These intricate decisions allowed Montpellier the chance to make "Women Talking" feel both as deeply personal and as visually grand as the idea of women finally taking control of their lives.

Judith Ivey leaned on indecisiveness to inform her Women Talking performance

The variety of female perspectives explored in "Women Talking" means that older voices are also given a lot of time to shine in the spotlight. Among those older voices is Agata (Judith Ivey). While some prominent characters in "Women Talking" are firmly determined to fight back or resist the status quo from the very start of the story, Ivey explained to RogerEbert.com that she played Agata as someone more indecisive at the beginning of the script. Agata relished the chance to hear a debate between the members of her community so that she could have more information on where she wanted to go in the future.

Because of this interest, Ivey saw Agata as someone who ensures that democracy endures, even in tense and brutal times. Her interest in the concept of democracy replaces a firm idea of how to handle the role of women in the Mennonite community going forward, at least at first. Ivey also leaned on Agata's age to make her somebody who could be a grandmother figure to even those who weren't blood relatives. There's an experienced and calming quality to Ivey's presence that makes her performance as Agata truly flourish and gives one of the older voices in "Women Talking" some incredible power.

The narration changed drastically in post-production

The original "Women Talking" novel presents its story through minutes recorded by August, making him ostensibly the point-of-view character. As explained in a Variety profile, Polley's initial script would've somewhat maintained this perspective by having the feature be narrated by August. Editor Christopher Donaldson noted that this consistency with the source material was present in the shooting script all the way through production. However, when he and Polley began to edit the movie, something didn't feel quite right. While August was integral to the original novel, it was decided that he shouldn't be the voice of the film version of "Women Talking."

In a major post-production change, Kate Hallett's 16-year-old character Autje became the narrator. Hallett was brought back in after photography wrapped to record brand new lines of narration, while an opening scene focused on August functioning as a teacher to some boys was brought later into the runtime. Overhauling the narration meant reconstituting certain pieces of footage or lines of dialogue into now being Autje's reflections on the past. An extraordinary amount of effort and creativity was needed to pull all this off, but Donaldson was ecstatic with his experience editing "Women Talking." Getting to overhaul a film in the edit while remaining true to its spirit isn't a challenge that comes along every day, but this complete reframing in narration offered up a unique opportunity.

Hildur Guðnadóttir's unique approach to the score

"Women Talking" is often a movie that remembers to keep things simple for maximum emotional impact. In the hands of this cast and Sarah Polley's screenplay, two human beings connecting can be enormously affecting. Composer Hildur Guðnadóttir took cues from this stripped-down intimacy in fashioning the score for the movie. Guðnadóttir explained to The Credits that her biggest guiding star creatively was making sure the music was streamlined and made use of instruments that the characters themselves would be familiar with.

This meant leaning heavily guitars and bells, with Guðnadóttir finding the latter instrument to be especially interesting, since it evoked the religious upbringing of the characters. She also wanted to communicate a claustrophobic quality with the music, a detail that subtly reinforced how urgently these characters need to change the status quo of their respective existences. Within the subdued nature of her score, Guðnadóttir proved vital in reinforcing the emotions that the "Women Talking" characters experience as they allow themselves to be vulnerable. It's just another aspect of the film that excels because of — rather than despite — its restrained qualities.

Women Talking was a breakthrough movie for Hildur Guðnadóttir

Gaze upon the filmography of composer Hildur Guðnadóttir and one will see an avalanche of impressive credits and artistic accomplishments in just a handful of years. However, Guðnadóttir noted to The Credits that one thing missing from her career before she worked on "Women Talking" was a feature-length collaboration with a woman director. Getting to artistically mix with writer-director Sarah Polley left Guðnadóttir feeling rejuvenated creatively, and she felt especially grateful to experience working within a predominately feminine artistic domain (other key crew members of "Women Talking" were also women) for the first time.

Not only that, but the central subject matter nd emphasis on a variety of ladies standing up to speak against injustices moved Guðnadóttir beyond just her exploits as a composer. After working on "Women Talking," Guðnadóttir was more determined than ever to cling to optimism and a fighting spirit for a better tomorrow. Talking about what she took away from being the experience, Guðnadóttir was upfront about how many hardships still endure in our world, but she was also candid about not giving up on the idea that the future could be better. Even given her extensive career as a composer, "Women Talking" clearly inspired unprecedented emotions and experiences for Hildur Guðnadóttir.

Sarah Polley worked diligently to create a safe environment on Women Talking

Sarah Polley has been open about her negative experiences as a child actor on the set of Terry Gilliam's "The Adventures of Baron Munchausen." In the pages of her book "Run Towards the Danger," Polley details how Gilliam's erratic filmmaking style resulted in significant lapses in safety on the film's set. This was especially true during a stunt gone haywire that left Polley shaken and Gilliam allegedly uninterested in the young performer's safety. It was a nightmarish experience that has impacted how Polley conducts the sets that she directs as an adult, including "Women Talking."

Polley elaborated to IndieWire that as a director, she endeavors to make sure her sets are incredibly safe. Not only that, but she also aims to have a demeanor that makes people feel comfortable to question her when they feel physically or emotionally unsafe. Whereas Polley felt a barrier between herself and Gilliam on the set of "Munchausen," she was conscious of leaving herself open to any kind of dialogue between herself and her cast and crew. There was also a doctor frequently on the set of "Women Talking" who could help members of the production navigate intense feelings surrounding the heavy material of sexual assault and its subsequent trauma. Her career in Hollywood began with traumatic experiences stemming from negligent filmmaking, but the "Women Talking" set demonstrated the measures Sarah Polley has taken to create more welcoming work environments.