Whistle While You Read These Facts About Snow White

If you've ever enjoyed any Disney movie – or really, a movie from any American animation studio — you have "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" to thank. After decades as a sideshow, Walt Disney's ambitious production proved animation was ready to become the main attraction. For good and for bad, "Snow White" set the formula Disney and its imitators would return to hundreds of times with its story of a beautiful princess, an evil stepmother, cute animals, and feats of magic. But no matter how many animators return to the same well, few of them have ever created a world as fully realized as Snow White's fairy-tale kingdom. And very few have haunted nearly a century's generations of children the same way with iconic images as beautiful as the seven dwarfs marching home in the sunset or as nightmarish as the horrible creatures of the dark forest.

Adapting this simple story became the most complicated project Disney had ever undertaken. The studio had to be rebuilt nearly from the ground up to make something more technically and artistically accomplished than they'd ever tried before. It was a long, hard process, and it's full of stories the Brothers Grimm would have killed for. Here are just a few.

Some of the biggest names in entertainment suggested ideas for Disney's first feature

Even before "Snow White," the success of Walt Disney's "Mickey Mouse" and "Silly Symphonies" cartoons had made him the most, and possibly only, famous animation producer of his time. This made him a lot of famous friends, and Neal Gabler's biography "Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination" describes how some of them got involved in the project that would eventually become "Snow White."

Walt's first idea was an even bigger undertaking that would have returned him to one of his earliest projects. His silent "Alice in Cartoonland" series had put a live actress in an animated world, and he planned to take the same approach to a full adaptation of Lewis Carroll's "Alice" novels. One of the biggest stars of the silent era and the co-founder of Disney's then-distributor United Artists, Mary Pickford, was already pushing for the starring role as Alice until Paramount scooped them with their 1933 adaptation. Given what a huge technical challenge "Snow White" turned out to be, Disney was probably grateful to have the excuse not to add the challenge of combining live action and animation to his plate.

Other friends and fans offered other intriguing possibilities. The original action hero and United Artists producer Douglas Fairbanks wanted to play the title role in "Gulliver's Travels," and the legendary author and cartoonist James Thurber suggested Disney take on more adult material by adapting Homer's "Iliad" or "Odyssey."

Snow White was based on the first movie Walt Disney had ever seen

The story Disney eventually settled on for their big coming out party as a feature studio couldn't have been more personal to the studio's founder. In fact, there probably wouldn't be a studio without it. Neal Gabler describes the first movie Walt ever saw as a young newsboy in Kansas City. The local paper had rented out the Kansas City Convention Hall to house a special screening for their delivery boys. To accommodate the 67,000 kids who showed up, the convention hall set up four screens, all showing a silent film of "Snow White." The primitive hand-cranked projectors were slightly out of sync, but to young Walt, that was a feature, not a bug. Able to see them all from the balcony, he had a truly magical experience outside of time, where he could look on one screen to see what was about to happen on another.

This moment obviously made a big impression on Walt Disney, and you can see its influence in both "Snow White" and another massive undertaking decades later, Disneyland. Ever since it opened in 1955, the park has included a recreation of Disney's turn-of-the-century childhood in Main Street USA, including the Main Street Cinema, where you can watch Disney's earliest "Mickey Mouse" shorts in the same four-screen format that introduced Walt to the movies.

Walt Disney told the story so expressively he almost got arrested for assault

While most producers keep out of the day-to-day business of movie storytelling, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was a vitally important to Walt Disney, and he took it so seriously he wasn't afraid to look silly. While his brother and co-producer Roy Disney was away in New York in 1933, one staffer, quoted in Gabler's book, caught him up on business in Burbank, saying Walt held "a business meeting ... for no good reason" before going on to describe what may have been the most important meeting in the studio's history. This was where Walt introduced "Snow White" to his staff, and he didn't just talk about it — he got all into it. "The way that boy can tell a story is nobody's business," the staffer said. "I was practically in tears during some of it."

Walt continued to sell his friends and collaborators on the story this way, and occasionally, he may have gotten a little too enthusiastic for his own good. Visiting his old friend Walt Pfeiffer in Chicago, Disney acted out the whole story on their way through the Field Museum of Natural History. By the time he demonstrated how the vultures would swoop on the old witch, Disney had attracted so much attention a security guard came in to "rescue" Pfeiffer, and the two men had to sneak out before the guard could throw them out.

Snow White could have had a long, strange trip to the dwarfs' cottage

Feature filmmaking didn't just push the Disney studio to new levels of craftsmanship — it demanded a complete change in approach. Most of their shorts up to this point had used bare-bones stories to set up loose collections of gags, but a 90-minute movie needed a stronger structure. Compared to the studio's later, more polished work, it's easy to see the growing pains: scenes like the animals cleaning the dwarfs' cottage or the dwarfs washing up could easily be chopped up and released as "Silly Symphonies" shorts.

But you can see the movie's roots even more clearly when you look at the versions of it that didn't make it to the screen. In "The Art of Walt Disney," Christopher Finch shares some early, even more episodic versions of "Snow White." The sequence of Snow White running through the dark woods to escape the Queen is so iconic it's hard to believe it lasts just over a minute. It's even harder to imagine it could have had the same impact if Disney had stretched it out as long as they planned to in the first plot outline.

This version would have taken Snow White on a whole Odyssey's worth of journeys through strange locations before she even met the dwarfs, including the Morass of Monsters, the Valley of Dragons, Sleep Valley, Upsidedownland, and Backwardland. The story team got as far as developing possible gags for these locations like birds flying tail-first and trees growing roots-up before they realized a movie called "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" could only drag its feet so long before it got to the dwarfs.

Lucille LaVerne could switch from the beautiful young queen and the ugly old witch by taking out her teeth

Snow White's stepmother set the template for hundreds of animated and fantasy villains to come, partly because she offered two characters for the price of one. There's the elegant queen who was "the fairest in the land" until Snow White reached maturity, and the unforgettably ugly old hag she disguises herself as to kill her stepdaughter. The disguise requires her to be completely unrecognizable, and she is, right down to her voice — but one actress embodied both roles.

In their article "Who Was Lucille LaVerne?" Cartoon Research examines the woman behind the witch, quoting sequence director Bill Cottrell: "When the voices were brought in, there were radio shows that had witches in them, old crones. They all had a pattern that was a cliché ... After seeing a bunch of these, they all seemed rather uninteresting because you'd heard the same thing on radio for so many years." But that changed when LaVerne shook him awake — "It rang over the soundstage," he said of her cackle. "It was blood curdling."

Disney had originally planned to cast separate actors as the Queen and her false face, but LaVerne was too good at both to play just one. At first, Cottrell wasn't impressed with LaVerne's peddler, but then she excused herself and came back to the recording booth with a perfect take. Her secret? "I just took out my teeth," she explained. Walt was impressed. When asked about a script rewrite for the witch, he just said, "All the dialogue sounded bad to me until she read it."

Snow White gave Disney a bigger canvas — literally

"Snow White" was orders of magnitude bigger than anything the Disney studio had done before. This meant growing, both in terms of real estate and in terms of staff taking it up. It meant the animators had to grow as artists, turning Disney into a combination studio and art school. It meant new technologies, like the massive multiplane camera that allowed the backgrounds to move in perspective.

Disney had to change in subtler ways, too. Christopher Finch describes the methods and material Disney had used up until then, including the 9 ½ by 12-inch sheets of paper all the animators drew on. This was more than adequate for the shorts, with their small casts going through simple actions. But to cram Snow White, all seven dwarfs, and who even knows how many of their animal friends into that space would have been impossible, especially while doing all the complex camera moves the movie required.

So the studio had to overhaul its whole process, designing and building not just drawing paper but painting boards and celluloid sheets and frames in bigger dimensions. This still wasn't enough to draw the characters in detail against the long, narrow backgrounds needed for tracking shots, so the technicians developed a way of reproducing drawings at a smaller scale — no small feat over a decade before Xerox even existed.

Snow White's wearing real rouge

"Snow White" no longer seems as revolutionary as it did in 1937, now that later films have taken its innovations for granted and frequently left them in the dust. But the movie still has some advantages over its more sophisticated successors, especially in its textures, which somehow approach photorealism while retaining a painterly, storybook quality. Most animated movies since then have used simple, flat colors, but "Snow White" embraces the full spectrum with its beautiful watercolors.

Even that medium wasn't subtle enough for all the effects the animators wanted, and Christopher Finch quotes animator Frank Thomas on his woes with Snow White's complexion. Her "skin white as snow" came back from the ink and paint department looking sickly pale, and every attempt to put a little healthy color in her cheeks "made her look like a clown." Finally, an anonymous ink-and-paint girl suggested that instead of trying to simulate it, they just paint rouge straight on the celluloid. When Walt didn't understand what she meant, she pulled out her makeup kit and demonstrated then and there.

The producer still had some reservations, though: "Walt said, 'Yeah, but how the hell are you going to get it in the same place every day? And on each drawing?' And the girl said, 'What do you think we've been doing all our lives?'"

Disney divided the production up by emotion

All this technical improvement wasn't just to show off — Walt Disney believed it was essential to make his cartoon characters real enough to genuinely move audiences. Up until that point, the studio had rarely attempted to get any emotional reaction other than laughs, so the learning curve was steep. It took over two years after the first story conference before Walt decided his animators were ready, and even then, he introduced a deliberate schedule that would allow them to learn on the job. The gag scenes were the same old thing the studio had always done, give or take some added polish, so that's where they started. After that, they moved on to the scary scenes — and based on how many kids have been scarred by the faces of the old peddler or the hungry trees, they were more than up to it. Finally, they tackled the most emotionally challenging scenes — Snow White's apparent death, funeral, and so on.

You could infer that much from the schedule, but Neal Gabler makes it explicit with a memo from Walt on his prize animator, Hamilton "Ham" Luske: "It is possible that with the experience Ham will gain by his work, plus his native ingenuity and ability, he will be able to handle all the Snow White action." And by the end of production, the animators were able to handle her just fine and move on from there to the even more sophisticated characterization in later movies like "Fantasia" and "Bambi."

The story department introduced some passive-aggressive signage

Anyone who's ever had to collaborate with anyone else, especially on the dreaded school group project, knows how challenging it can be. Everyone has different ideas on what the result should look like, and even when they agree, they can still clash over how to get there. So you can only imagine the stress of working with the hundreds of conflicting visions you'd get from a production this size.

With the pressure on to complete "Snow White" in the home stretch, interdepartmental tensions couldn't help but rise. Intimidated by Walt's demanding perfectionism, the animators fussed over every frame. But perfection and comedy don't always go together, and two factions developed: the new, "arty" animators who had gone through the life drawing courses, and the old guard who didn't care about anything but the laughs.

The story department apparently chose a side, based on the sign they posted on their door during production: "It was funny when it left here!"

The budget was stretched so thin the animators had to do their own advertising

The Disney studio spared no expense in bringing "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" to the screen. Unfortunately, that didn't leave much time and money for it once it got there. The documentary "Disney's First Feature: The Making of 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'" (streaming on Disney+) discusses how the artists were still finishing their animation with the premiere just two weeks away. Art director Ken Anderson recalls, "Because we had no money to advertise the picture, we got these little placards about a foot and a half high, and it was our job to go through Hollywood. All of us in the studio went and taped these on the telephone poles. It was the only way people knew about it."

That's certainly a long way from the inescapable multimedia marketing campaigns Disney has undertaken for its more recent features. But this was their first one, so it's no surprise they were still figuring it out. And it paid off — advertising or no advertising, "Snow White" was a smash hit, finishing as the top grosser of the year.

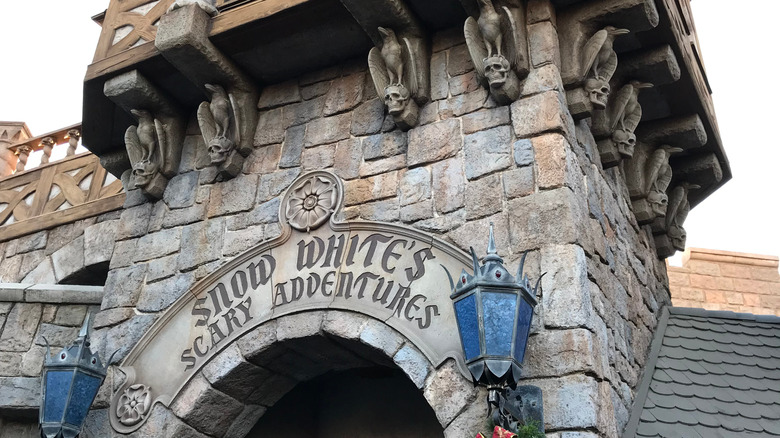

Disneyland needed a high tech solution to get people to quit stealing the witch's apple

Disney proved the viability of a new medium with "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," and they did it again when they opened Disneyland in 1955. Amusement parks had been around for centuries, but Disneyland combined thrill rides with a meticulously constructed fantasy environment, creating possibly the first true theme park, and certainly the most ambitious up to then. Disney couldn't mark this new milestone without paying tribute to the other, and "Snow White and Her Adventures" has taken guests inside the story ever since opening day. It's undergone a lot of remodels and rebrandings since then, turning into "Snow White's Scary Adventures" and finally "Snow White's Enchanted Wish."

Some of these were big, high-tech changes that arrived with all the hype the Disney machine could manage, but one is almost invisible. While the ride still uses three-dimensional figures much like the ones that have been there since 1955, the apple the witch offers to guests is holographic. According to "The Disneyland Encyclopedia," this was a strictly pragmatic choice. Before the "Scary Adventures" incarnations opened in 1983, the apple was a popular souvenir for guests to steal, and the Imagineers apparently figured the then-state-of-the-art technology was more cost-effective than having to replace it over and over. Now, if you try to grab the witch's apple, your hand will go right through it.

Disney's Imagineers had to be creative to make Snow White's Grotto usable

In 1961, Disneyland welcomed a second "Snow White" attraction with "Snow White's Grotto." "The Disneyland Encyclopedia" explains that the themed area came to be after an anonymous Italian sculptor gifted the studio a set of statues of the movie's cast. They were a natural fit for Disneyland, but they presented a problem: all eight statues were the same height, making Snow White dwarf-sized.

Disneyland Imagineer John Hench was able to solve the problem with a little bit of optical trickery. First, he made sure Snow White wasn't displayed next to the dwarfs. Second, he placed her at the top of the grotto, using forced perspective: Since Snow White is farther away than the dwarfs, she appears to be taller. It probably helped that the Disneyland team already had experience with these tricks — it's the same method they used to make Sleeping Beauty's Castle and Main Street USA seem to be built at human scale all the way up instead of just the levels open to guests by making the upper levels progressively smaller, seeming to recede into the distance.