Ben Affleck's Air: Do Historical Dramas Need To Be Factual To Be Good?

Everything from "Star Wars" to the Shakespearean workplace drama you relay to your roommate at the end of a rough day at the office is a distorted representation of truth. They are subjective compilations of singular perspectives, selected events, emotions, and occasionally the odd unreliable memory or two, all organized and presented in the service of communicating a clear narrative idea. It's this quasi-deceitful element of presentation, however, that makes stories so impactful in the first place.

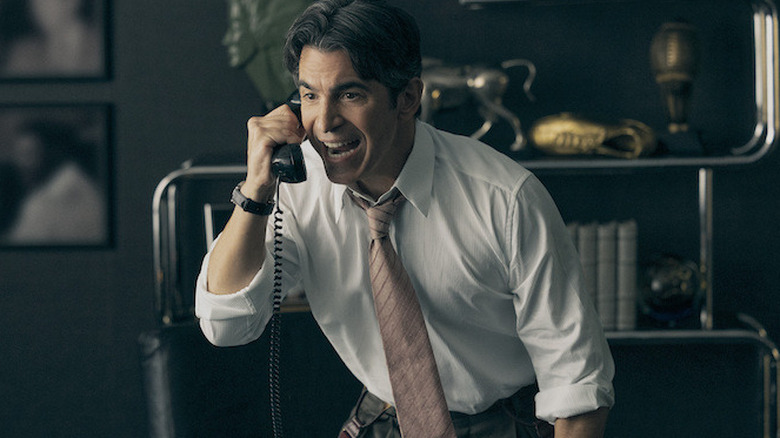

When Matt Damon, as real-life Nike marketing executive Sonny Vaccaro, delivers his climactic speech about legacy to Michael Jordan's family at the end of Ben Affleck's historical sports drama "Air," you feel as though you can understand exactly what it was like to be in the room with him that day — to understand with urgency the importance of believing in someone. In "Air," Sonny's speech changed the world. In real life, the words in that speech didn't exist until screenwriter Alex Convery made them up. Does that matter?

Does it matter that Vaccaro didn't actually study the tape of Michael Jordan's game-winning shot against Georgetown in the 1982 NCAA Division I men's basketball finals? Or that he was at home with his wife when the deal finally closed? Or that he met the future NBA star before he even spoke to his mother, Deloris? If "Air" altered these facts — and omitted other, more troubling ones — is it less effective as a film? Does it matter anymore if a "true story" isn't really true?

Air swaps accuracy for subjectivity

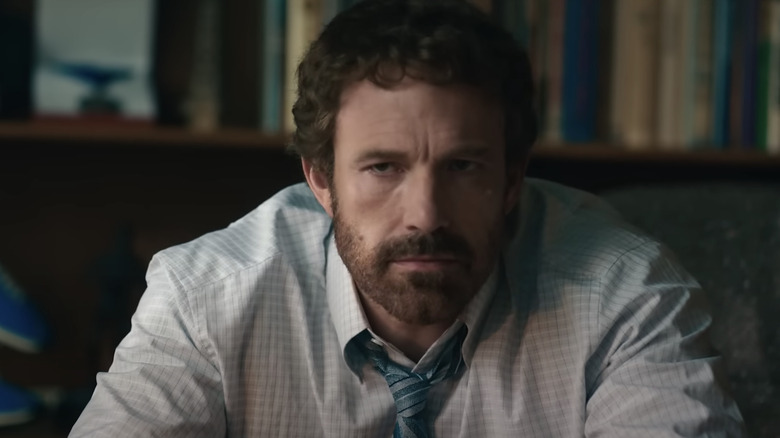

Charitably, it could be argued that "Air" makes changes to communicate the subjective truths experienced by historical figures. The original screenplay (titled "Air Jordan") only had one line for the character of Michael Jordan's mother, Deloris. It was only after director Ben Affleck met with Jordan himself that he understood how important she was to the athlete signing with Nike.

As seen in the film (and as stated by the real Sonny Vaccaro), the only way to convince Michael Jordan to take a chance on Nike was through his parents. To communicate this idea in a dramatic way, "Air" made Deloris' character (Viola Davis) a physical barrier between the shoe company and the star they were courting. This is a perfect example of how historical dramas can alter events while still depicting something real, often in a more effective or efficient way.

In reality, Vaccaro met with Michael Jordan at Tony Roma's with George Raveling (portrayed in "Air" by Marlon Wayans) before Vaccaro and Deloris Jordan began speaking over the phone. Portraying events as such would have been more factual, sure, but it would have undercut Deloris' importance to the story in a way that would arguably be unrealistic to the people actually involved.

"Air" consistently prioritizes placing the audience within the headspace of its subjects, rather than trying to show each and every event as it occurred. These efforts to dramatize the story manage to prevent the genuine emotional throughline of Sonny and Deloris' relationship from getting lost in the messiness of reality.

This subjectivity comes at the expense of meaningful education

As film analyst Patrick H. Willems once said, "movies are not math." This is to say, they are not meant to be repeatable equations that hold up in real life but works of art that can inspire emotional reactions within the audience. They're not education — they're entertainment. The implications of this statement become complicated when dealing with equally complicated historical figures.

Some may have preferred to see even a fictional Phil Knight being forced to reckon with (or at the very least acknowledge) Nike's alleged use of sweatshops — to have that be an inescapable aspect of an otherwise flattering biopic. Ultimately, however, it is difficult to imagine such discourse working within a film like "Air." In the story Ben Affleck and Alex Convery chose to tell from the perspective they chose to tell it from, the character of Phil Knight can't be the man he was to his workers or to the press, but the man he was to Sonny Vaccaro, Rob Strasser (Jason Bateman), and Michael Jordan. For all depicted within its runtime, "Air" doesn't pretend to share complete biographies, but snapshots of subjective truths — of how they saw each other and themselves.

To Sonny, David Falk (Chris Messina) was a loud obstacle in his mission to sign Nike's first star player — to that star player and many of his peers under Falk's purview, the sports agent was an invaluable partner. In his own mind, Sonny saw himself as standing alone against impossible odds — which may be why the film felt it prudent to omit his wife from the narrative, lest they distract the audience from the psychological truth of the moment in favor of a flat, objective recreation.

What are the moral and artistic consequences of this sacrifice?

When trying to examine how historical facts impact the actual entertainment value of a story, we must recognize that the line is often drawn according to one's own personal moral boundaries.

If a man, living in our real world, gets into a car accident at a mall parking lot while driving 88 miles per hour in a straight line during a misguided attempt at time travel, chances are "a movie said I could" wouldn't hold up as a defense strategy during the inevitable civil suit to follow. But what if instead of "lying" to us about the capabilities of a DeLorean, a film "lied" to us about a real person? What if it made them seem more noble, cruel, ineffectual, or successful than they were in real life — could that potentially be dangerous, if not physically, then morally?

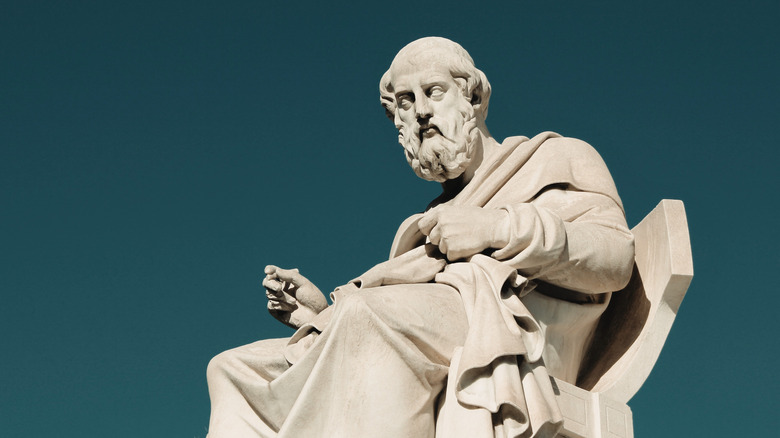

Film scholars, philosophers, and Friday morning pearl clutchers alike have been trying to wrestle with questions like this one quite literally since the conception of storytelling itself. If you left "Air" feeling like it was well made and passably entertaining but morally questionable in its historical omissions, you may find yourself aligned with one of the world's first art critics.

In 378 BCE, Plato (of "don't eat that no matter how good it smells" fame) wrote in "The Republic" that stories were so inherently misleading as to be a moral threat to the youth of his utopia — so much so that he stopped just short of banning them altogether. As a concession, he admitted that stories could be told so long as they were morally educational, depicting righteous men being rewarded for their good deeds while triumphing over those that would do society harm. Good guys win, bad guys lose — simple, right?

Can you tell a morally correct true story?

The trouble is, "Air" represents a sort of paradox in this line of thinking, especially when dealing with real-world figures (as stories often have even since the Biblical era). "Air," the story of principled men who succeed because they work hard and respect their client and his family, is a morally "correct" story, but an incomplete one — a lie of omission, some will surely argue. But a hypothetical, unflinching version of "Air," which depicts a company becoming successful despite accusations of sweatshop labor would be a morally "incorrect" truth. It would also lack the focus, style, and impact the real "Air" ultimately delivers.

Neither versions fit in Plato's Republic, but more importantly, their contrast forces the frustrating question at the heart of the matter: what is the morally correct way to approach history, when history is so often the story of men being rewarded for behaving immorally? And for our purposes, how do we engage with those stories as an audience?

Art reveals itself in what it asks us to believe

Luckily, one answer to this question will also help us determine whether or not these factual omissions and inaccuracies harm the story's entertainment value. Author, researcher, and art analyst Erich Hatala Matthes argues in his book "Drawing the Line" that when trying to assess a piece of art on an ethical level, it is beneficial to examine what the work is asking of its audience.

For example, "The Greatest Showman" was widely criticized for how it portrayed the story of the infamous businessman P.T. Barnum. It didn't merely ask the audience to empathize with a morally bankrupt character (many great stories do, after all) — it asked them to see his exploitative ambitions as fantastical or even admirable. For anyone with even vague knowledge of how circuses treat their animals, watching Hugh Jackman heroically riding in on an elephant at the end of the film is sure to be uncomfortable.

What does Air ask us to believe?

"Air" asks comparatively little of its audience, mostly that they believe that passion, effort, and carefully placed faith can overcome any obstacle. As such, its dreamy perspective is mostly innocuous and not likely to distract most viewers. However, as a direct consequence of taking such a sentimental approach to this story, the film's obligatory "where are they now?" ending rings hollow. David Falk's role in the controversial 1998-1999 NBA lockout was omitted, while Phil Knight is sent off into the sunset with a slyly saccharine sentence about his philanthropic endeavors — forget the fact that he once withdrew a $30 million donation to the University of Oregon because they backed the Workers Rights Consortium. In its closing moments, the film is no longer asking you to believe in its characters and themes — it's attempting to educate. It's the crossing of this boundary that may have some leaving the theater with a rock in their shoe.

Overall, "Air" soars when it sticks to the scope of its tightly composed narrative and avoids diverting the emotional investment of the audience to its complicated real-life subjects. However, as an audience, we must also learn to accept the phycological truths historical dramas can offer without uncritically internalizing the narrative as factually comprehensive or even accurate. Stories can spark real change, illuminate aspects of history you may have been ignorant to, or show you experiences you had never imagined — but the stories themselves are just stories.

Stories aren't real — what they inspire within us is.