Grease: Rise Of The Pink Ladies Betrays Bad Girls For Girl Power (& Misunderstands Today's TV Landscape)

Contains spoilers for "Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies" Episodes 1 and 2.

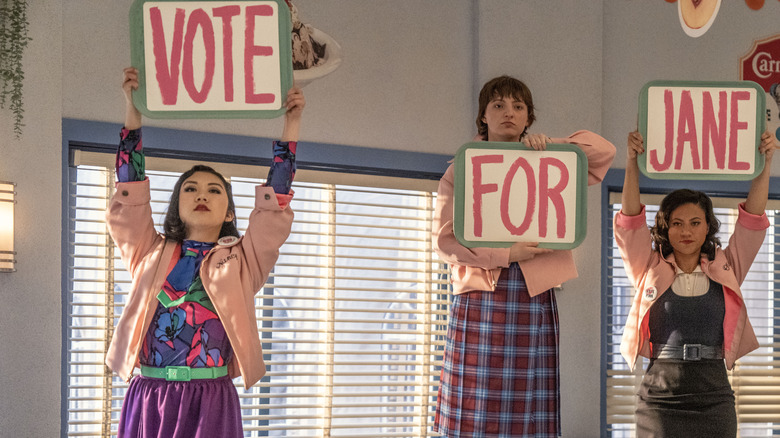

During the second episode of "Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies," our central protagonist, the nerdy Jane Facciano (Marisa Davila), explains her central goal during a campaign speech as she runs for student body president: to ensure Rydell High is a place where people can "be themselves."

Y'know, just like those virginity-shaming, gossipy, cliquey, fat-shaming, snarky, disaffected Pink Ladies who will rule Rydell four years after she graduates, right?

Oh boy, does "Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies" forget who the Pink Ladies are going to be in "Grease." It takes surface elements of their look, rebelliousness, and attitude to try to craft a proud feminist group. But the notion of this show's message — freedom and fun for everyone, forget tradition, screw racism and gender boundaries, and girls can fix cars too — sits at odds with what this group represents in the rest of the franchise. And it's absolutely not helped by the fact that this is allegedly a prequel, which requires a massive amount of social decay to occur for any of what happens in "Grease" and "Grease 2" to make sense.

It's hard to believe that in four short years this group, which includes a character that is heavily coded as asexual, will morph into a gang who will mock Sandy Olsson (Olivia Newton-John) for not putting out. This series misunderstands its central bad girls, falls victim to tropes, and incorrectly calculates how much the media landscape has changed over the past few years.

The Pink Ladies were never nice people

There's something "Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies" gets immediately wrong about "Grease." The original Pink Ladies are so-called outcasts from Rydell's social strata, sure. They're so-called "bad girls" with complexities all of their own, of course. However, they're also pretty terrible people, who are unwelcoming to outsiders.

One needs only to look at how most of the Pink Ladies treat Sandy. And that's also the problem with Sandy's ... I guess you could call it, uh, friendship, with everyone else in the clique but Frenchy (Didi Conn). They're all downright mean to Sandy, mocking her inability to fit in and for not being as cold as they are: that cruelty is only resolved by Sandy turning herself into a leather-wearing, cigarette-smoking bad girl. The kindest person in the group, Frenchy, is dumped on by the narrative, having her beauty school dreams stomped to death. Pretending this group represents a bunch of rah-rah, girl power, down-with-the-patriarchy rebels conflicts with the fact that Pink Ladies just a generation removed from the show's events will service the male gaze with glee. This disparity causes the viewer such cognitive whiplash that one's left wondering if the producers actually watched the original film, or just a YouTube highlight reel. The closest the original "Grease" gets to feminism is a brief shot of Rizzo looking thoughtful when Principal McGee (Eve Arden) suggests that among Rydell's class of 1959 there lies a possible president of the United States.

Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies serves up mixed messages

In "Rise of the Pink Ladies," every single proto-Pink is the object of class-wide scorn in a way that Rizzo only managed to achieve with her pregnancy scare. Aside from the accidentally scandalous Jane, Rydell's own Hester Prynne, the pugnacious Cynthia Zdunowski (Ari Notartomaso) is a tomboy type who yearns to be a T-Bird, but they scorn her. Ambitious Nancy Nakagawa (Tricia Fukuhara) dreams of fashion school far away, but her friend group is disintegrating and taking her college plans with them. And Olivia Valdovinos (Cheyenne Isabel Wells) is stuck dealing with the aftermath of a disastrous grooming situation with her English teacher, which has ruined her academic prospects and leaves her picking up the pieces when he blames her for the uproar. They end up in the principal's office together, and they form a bond to scorn the gossipers. It's just that simple.

The messages here are mixed: it's great to be different, but the biggest act of rebellion in the whole show involves the four girls mooning their class, a picture that ends up in the paper. And sometimes the lessons the series brings forth are arguably made worse by its connection to original film.

It's not that a show about the Pink Ladies couldn't work. See "Yellowjackets," for example, to see how complex female representation on TV can be more than just empowerment. However, the notion of using these characters for a "girl power" narrative simply falls apart under the contradictions with what the Pink Ladies represented in the original film.

Grease: The Rise of the Pink Ladies' status as a prequel makes it even worse

"Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies" values sisterhood and friendship to an extremely high degree. If the girls from the original "Grease" were good friends to one another, this might make sense, but as we covered above, they were as terrible to one another as they were to outsiders. Consider this painful example: Rizzo confesses to Marty that she thinks she's pregnant, and Marty nearly-immediately gossips about this to her own boyfriend, which in turn gets back to Kenickie (Jeff Conaway), the possible father-to-be. If the T-Birds captured by the movie are generally jerks, then so are their counterparts. That's not even getting into how the movie fat-shames Jan (Jamie Donnelly).

The show doesn't explain why there's such a huge switch in social norms between its setting and that of the original film. It sets up too many unanswerable questions. If the Pink Ladies were created as a form of rebellion against the T-Birds, why does it later become Pink Lady Lore that the two cliques must only inter-date, with no outsiders allowed to interlope? "Grease 2" has a specific subplot that bars the film's central couple from getting together because of this.

In fact, even "Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies" suffers from this dissonance, because it's hemmed in by what "Grease" will do with itself. Watching the show on its own merits, it's hard not to feel saddened by where this is going to end up, just four years later. By 1958, there are still no female T-Birds, most of the women of Rydell will not sport unique ambitions, and the Pink Ladies will exist as little more than supporters for the T-Birds' activities. Not quite a feminist ending.