Renfield Seemingly Rounds Out A Trilogy Within Universal's Dark Universe

While the Rotten Tomatoes reviews for "Renfield" may show that it's on its way to becoming the horror-comedy hit of the spring, it was developed under arguably inauspicious circumstances. As some may remember, the cinematic universe gold rush was just beginning in the early 2010s, after Marvel Studios' "The Avengers" became an unprecedented critical and commercial success. Companies began scouring their back catalogs of intellectual property to see what iconic characters could one day share a highly lucrative world together. Marvel and Disney dramatically expanded their Infinity Saga, Warner Bros. fast-tracked Zack Snyder's DC projects, and Universal created the Dark Universe.

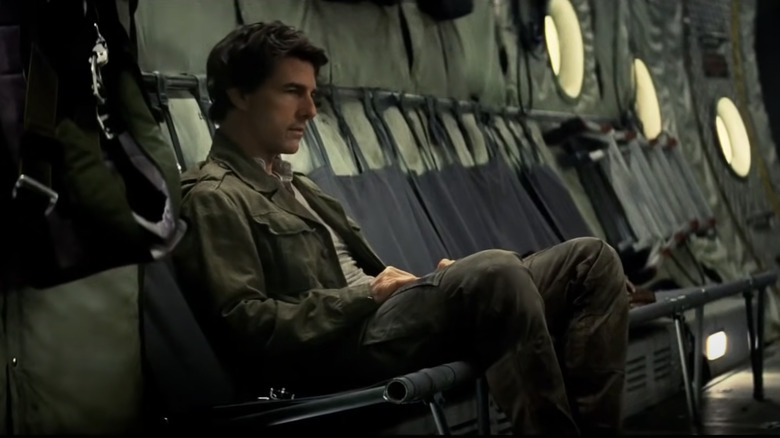

Marked by overconfidence and false starts, the Dark Universe is widely considered to have launched and crashed with Tom Cruise's reboot of "The Mummy" in 2017. Despite an opening sequence that sets up the story and a star-studded photo shoot (with all the gravitas of a high school yearbook ad), the film was considered a failure on all fronts.

While Universal still weighed the future of the Dark Universe, comic book writer Robert Kirkman approached the studio with his pitch for "Renfield," wanting to find some use for the character of Dracula within the franchise despite its toxicity following "Dracula Untold." In a weird way, this makes "Renfield" the final film in a protracted Dark Universe trilogy whose films have surprisingly harmonious themes.

A dark universe of relationship trauma

This very hypothetical Dark Universe trilogy — which consists of 2017's "The Mummy," 2020's "The Invisible Man," and "Renfield" — works in concert to examine toxic relationships. It's an interesting direction for the horror franchise to take considering its classic iteration consistently depicted various levels of romantic and sexual victimization. In taking such dangers seriously rather than employing them for mere shock value, this "trilogy" actually has something of note to say.

Both "The Invisible Man" and "Renfield" are open and conscious in their aims. In wildly different ways, they tell the stories of relatively powerless people trying to escape intimate relationships with supernaturally empowered men, dramatizing the power imbalance that keeps so many survivors trapped in abusive relationships. A key difference is that "The Invisible Man" explores the limited options for justice and liberation available to survivors — especially women — as well as the horrific personal sacrifices they may have to make in order to escape, whereas "Renfield" paints a more optimistic picture of how they can regain control of their life by finding strength through community.

How Tom Cruise's The Mummy fits into the trilogy

"The Mummy" is a bit more complicated as a piece of this puzzle, though it cannot escape consideration due to its clear (and often awkward) romantic and sexual underpinnings. From a certain perspective, however, it could be seen as the story of a manipulator being forced to reconcile with the pain he's inflicted upon others. U.S. Army Sergeant Nick Morton (Tom Cruise) seduces an archaeologist in order to steal a map that leads to ancient treasure — because of this act, Nick is cursed by an undead being who aims to seduce him into forfeiting his mortal body to the god of death.

This lens even clarifies the inclusion of Russell Crowe's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. During their battle, Hyde attempts to persuade Nick to his side through promises of power, arguably forcing the protagonist to confront his own duality — the swashbuckling "Jekyll" he sees himself as and the dark monster he's one stab away from becoming.

It might not be perfect, but it works

If you can look past the borderline exploitative sexualization of Ahmanet (Sofia Boutella) and the sexist stereotype of the siren luring men into danger, Nick's journey almost looks like one of genuine self-discovery. He learns what it's like to be on the other end of the emotional pain he's inflicted on others and succeeds by rejecting advances he may have once made himself ("I'm sorry. We are just never gonna happen. And it's not me. It's you"). After reviving the woman he mistreats at the start of the film, Nick admits that there is a darker side of him that he doesn't understand and must learn to control before he can trust himself around others.

Is it a perfect read of "The Mummy"? Not entirely. By this same logic, an argument could be made that his abusive nature (manifested in this theory through possession by the Egyptian god of death) is some sort of superpower — the same goes for Jekyll and Hyde. As much as they reiterate that these gifts are truly curses, the inevitable "Avengers"-style team-up would have surely undone such logic. However, those who watch "The Mummy" in the context of its two spiritual successors may find the viewing experience to be slightly richer and potentially more challenging.