Actors Who Were Forced To Take Over As A Movie's Director

Replacing a movie's director prior to production is a fairly common occurrence — filmmakers are courted, brought aboard a film, and drop out all the time — but to replace a director during production is a totally different manner. It's typically done because a problem with production has reached an untenable point. The director's vision might clash with that of their leads, producers, or studio, or a personal issue might befall the director. Whatever the case may be, replacing a director causes a huge and often costly break in the flow of production, one that producers hope to avoid. However, it's not an uncommon situation.

Many major filmmakers have been benched while actively directing a film: the list includes Bryan Singer on "Bohemian Rhapsody," Steven Soderbergh on "Moneyball," Edgar Wright on "Ant-Man," and Zach Snyder on "Justice League." In nearly all cases, a director is replaced by another filmmaker, but in a small number of cases, one of the film's actors steps in to complete the picture. The results have been mixed and controversial and involve huge stars being forced to take over as their own movie's director.

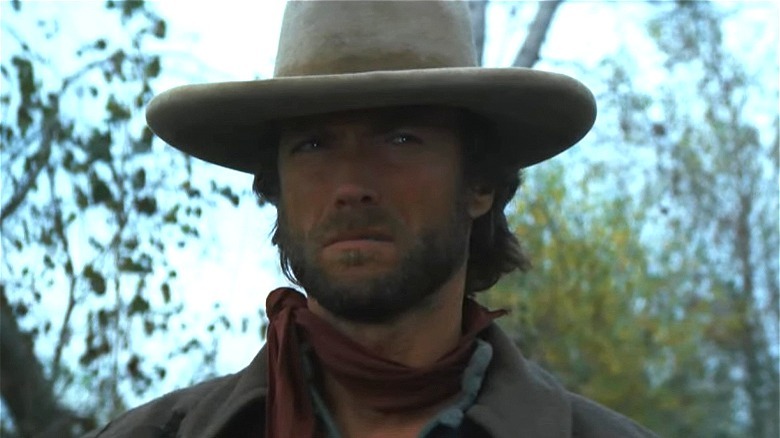

Clint Eastwood - The Outlaw Josey Wales

Actor-director Clint Eastwood is perhaps the actor most associated with taking over as director of a film after the original helmer stepped down or was let go. He's so linked with such a scenario that the Directors Guild of America (DGA) actually used his name for a ruling to address such changes. The Eastwood Rule, as it's known, was adopted after he convinced the producers of his 1976 western "The Outlaw Josey Wales" to remove director Philip Kaufman ("The Right Stuff").

Eastwood had grown frustrated with Kaufman's meticulous approach and sought to take over as director, despite the protestations of the DGA. After the film was completed, the guild established the Eastwood ruling, which imposed heavy penalties on any person associated with a film that dismissed a DGA member as director and took over in that capacity. Eastwood later found out how ironclad his namesake rule was during the making of 1984's "Tightrope."

The actor was again displeased with the pace established by that film's director, Richard Tuggle, who was making his directorial debut after writing "Escape from Alcatraz" for Eastwood. Though the actor couldn't remove Tuggle because of the Eastwood Rule, he reportedly went around it and directed much of the movie while allowing Tuggle to retain his credit. Eastwood also stepped in to direct "The Bridges of Madison County" after Bruce Beresford left the project, though his departure was due to creative differences with co-producer Steven Spielberg.

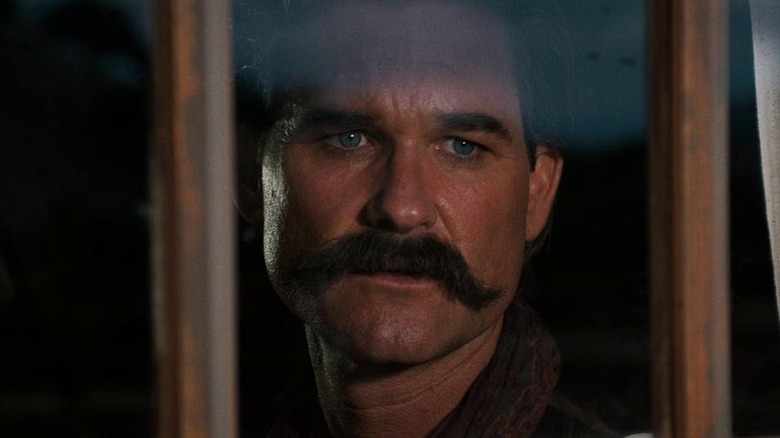

Kurt Russell - Tombstone

Though the 1993 western "Tombstone" remains a well-loved addition to the genre, the production itself was an incredibly difficult one, marked by crew departures, schedule conflicts, and script issues. Its biggest problem, however, was novice director Kevin Jarre, who according to a 1993 article in Entertainment Weekly, was unable to keep up with the film's breakneck schedule and was eventually fired by producers. According to many sources, star Kurt Russell stepped in to take the reins, reworking the script with producer James Jacks until journeyman filmmaker George P. Cosmatos ("Rambo: First Blood Part II") could take over.

How much behind-the-scenes work Russell put into the film was never well defined, In 2017, Val Kilmer, who memorably played Doc Holliday in the film, addressed (via Entertainment Weekly) longstanding questions about "Tombstone" on his website. "I'll be clear," he wrote. "Kurt is solely responsible for 'Tombstone's' success, no question." According to Kilmer's post, Hollywood Pictures, who co-produced the film, refused to give them more time to correct its many problems, forcing Russell to take over many production duties. "I watched Kurt sacrifice his own role and energy to devote himself as a storyteller, even going so far as to draw up shot lists to help our replacement director, George Cosmatos, who came in with only two days prep," the actor wrote. While Kilmer stops short of specifically crediting Russell with directing the film, it's clear that he rests the film's subsequent box office and critical success on its leading man's shoulders.

Robert De Niro - The Score

At first, Frank Oz seemed like a strange choice to direct the 2001 crime film "The Score," which features the powerhouse lineup of Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, and Angela Bassett as well as Marlon Brando in his final film role. Oz, a legendary puppeteer for "Sesame Street" and "The Muppet Show," had found success as a director on projects by his longtime friend, Jim Henson, but also displayed a talent for less family-friendly material, especially in comedies like "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" and "Bowfinger." Having directed such marquee performers as Steve Martin, Bill Murray, and Kevin Kline, Oz seemed more than prepared to guide his formidable cast in "The Score." However, he hadn't met Brando.

A mercurial presence throughout his career, Brando had earned a reputation for clashing with directors like Francis Ford Coppola, who struggled with the actor on "Apocalypse Now." The actor was on bad terms with Oz after he asked him to bring down the energy in his performance; the tension soon escalated to Brando calling Oz "Miss Piggy" and refusing to go to set while he was present. Eventually, De Niro was tapped to direct Brando's scenes, with Oz watching the scene through a video monitor and providing direction through an assistant.

In a 2007 interview for Ain't It Cool News, Oz graciously shouldered the burden of the conflict with Brando, claiming that he had been too hard on the actor. "My job was to nourish and support [the actors], and I was more confrontational because I thought I had to be tough with him," he said. "And I pushed him the wrong way."

Orson Welles - Black Magic

Despite having directed one of the most celebrated films in history — 1940's "Citizen Kane" – Orson Welles struggled throughout his career to complete his vision on many of his features against studio interference, funding problems, and a host of other production issues. Welles saw the completion of 14 films during his lifetime, with an additional two (1992's 'Don Quixote" and 2018's "The Other Side of the Wind") finally securing release long after the filmmaker died in 1985. Welles was also credited with having directed scenes or portions of a number of other films in which he appeared, including the 1960 costume drama "David and Goliath" and the thriller anthology "Three Cases of Murder," He's also frequently cited as the uncredited director of 1943's "Journey Into Fear," a thriller directed by Norman Foster, who had also co-directed much of Welles' uncompleted feature "It's All True."

Welles is also credited with serving as director for his own scenes in "Black Magic," a 1949 drama with the actor top-billed as hypnotist and con man Joseph Balsamo aka Count Caligostro. Several directors for the film, including Irving Pichel and Douglas Sirk, had come and gone before actor Gregory Ratoff took the helm; Ratoff was a friend of Welles' and a less experienced filmmaker, which has given rise to the notion that Welles handled his own scenes. Several sources point to the visual look of the film as evidence, most notably the use of light and certain angles, which were evocative of Welles' own directorial style. As a result, Welles is frequently cited as an "influence" on the film, if not an actual director.

Takeshi Kitano - Violent Cop

Japanese actor-director Takeshi Kitano has earned worldwide acclaim for violent, gritty thrillers like "Boiling Point" and "Hana-Bi," for which he served as star and director. These films served as an introduction to Kitano for most English-speaking audiences, but Japanese viewers had seen him as part of a comedy act, called Two Beat, which performed broad banter-based routines on television throughout the 1970s. In a conversation with The Hollywood Interview in 2001, Kitano said he knew his comedy career was short-lived and sought more serious roles, including a supporting turn in "Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence" with David Bowie. Audiences weren't ready for it and laughed when he appeared on the screen. "I was devastated," he said.

Kitano deliberately pursued serious roles in the years that followed, which led to his second career as a director. Cast as a ruthless, self-destructive police detective in 1989's "Violent Cop," Kitano was dismayed to find that the shooting schedule conflicted with his TV work. Production was halted as Kitano negotiated with the producers over his assignments, during which time the director, the legendary Kinji Fukasaku ("Battle Royale"), dropped out. The film's distributor then turned to Kitano to take over as director, who accepted the assignment and rewrote the film — initially intended as a comedy — into an uncompromisingly brutal thriller. "Violent Cop" transformed Kitano's career from a comedian to not only a dramatic actor but also a celebrated filmmaker, winning the esteemed Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for "Hana-Bi" aka "Fireworks" in 1997.

Johnny Depp - The Brave

How Johnny Depp came to direct the 1997 indie feature "The Brave" is a far more tragic story than the one depicted in the film itself. The film, based on a novel by "Fletch" author Gregory Mcdonald, stars Depp as a Native American man who agreed to die on camera as part of a snuff film to earn money to care for his desperately poor family. First-time producers Charles Evans Jr. and Carroll Kemp brought the film to Touchstone Pictures, which picked up the film for release. They also persuaded Touchstone to let Aziz Ghazal, a recent USC film school grad, direct the film. Shortly before the cameras rolled on "The Brave," Ghazal murdered his wife and daughter and then took his own life. Touchstone cut ties with the film soon after.

Though horrified by Ghazal's crimes, Evans and Kemp needed to complete the film, having sunk more than half a million dollars of their own money into the film. The pair brought the film to Depp, who eventually decided to not only star but also rewrite and direct the film. Though he brought significant star power, as well as high-profile friends like Marlon Brando and Iggy Pop to appear in it and do the music, respectively, and got the project an additional $2 million in funding, the film was dogged by negative reviews following its screening at Cannes. Pre-sales to international markets assured the film a release overseas, but "The Brave" never picked up a stateside distributor and was never formally released in the U.S.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Marlon Brando - One-Eyed Jacks

Marlon Brando has a history of butting heads with some of his directors. Among the filmmakers who fell afoul of his ego was Stanley Kubrick, whom Brando tapped to direct the 1966 western "One-Eyed Jacks." The actor had purchased the rights to the 1956 novel "The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones" intending to star in and produce the film and burned through an inordinate number of talented people to conceive a script, including Rod Serling and Sam Peckinpah. When it came to choosing a director, Brando sought out Stanley Kubrick, who had recently completed his powerful anti-war drama "Paths of Glory."

But according to an obit for producer Frank P. Rosenberg in the Los Angeles Times, creative meetings held at Brando's house quickly soured. Opposing visions, as well as Brando's personality quirks — according to Kubrick, Brando used a stopwatch to keep comments to under three minutes — led to Kubrick either being fired or walking off the picture, while Brando took up the helm for "One-Eyed Jacks." Production was two weeks behind schedule after only five days of shooting, and Brando left the editing of the four-plus hours of footage to others. Paramount, which released the film, delivered its own cut, which included a new ending. Brando disowned this version, though it did net an Oscar nomination for Charles Lang's gorgeous cinematography.

Prince - Under the Cherry Moon

The late Prince was a brilliant musical artist, creating some of the memorable and popular songs of the 1980s and '90s. He also possessed a magnetic stage presence that translated to film with his screen debut in "Purple Rain." However, his three attempts at directing a feature film showed that some creative pursuits were outside of his talents. The first of these was 1986's "Under the Cherry Moon," which starred Prince and Jerome Benton — the hype man for The Time — as brothers romancing wealthy women on the French Riviera. To direct the film, Prince tapped Mary Lambert, who had helmed stylish music videos for Madonna, Janet Jackson, and Eurythmics.

However, the creative differences between Lambert and Prince forced her to abandon the project after 16 days of shooting. Prince took over as director and, because the film was shot on location in France, avoided the DGA's "Eastwood Rule" that prevented actors from firing their directors and assuming the directorial role of their own films. As it stands, the rule might have helped "Cherry Moon," which drew dismal reviews and poor box office returns for its paper-thin plotting and cartoonish characters. Prince would direct three more films: the 1987 concert film "Sign O'the Times," which earned better reviews, and "Graffiti Bridge," a fantasy sequel to "Purple Rain" that took a critical beating in 1990. His final feature directorial credit came with 1994's "3 Chains O' Gold," which assembled videos for his album "Love Symbol" into a loosely connected plotline for a direct-to-video release.

George Clooney - Confessions of a Dangerous Mind

George Clooney took over as director of the 2002 film "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind" for one simple reason: he just wanted to get the film made. The comedy-drama-fantasy, adapted from "Gong Show" creator Chuck Barris' fantastical (and false) stories about serving as a CIA hitman, was stranded in development hell for more than a decade, passing through the hands of directors like David Fincher, Curtis Hanson, and Darren Aronofsky. George Clooney came aboard early on in the project's development, but production was halted over the budget, which was set at $35 million, and distribution rights. Eventually, Bryan Singer dropped out of the director's chair, leaving the spot empty.

Clooney made a bold pitch to Miramax, which had taken over funding the picture. "I thought, if I grabbed it and did it for scale, and got everybody else to do it for scale, we could get the film made for way under what it'd been budgeted at," he told the BBC in 2003. "That was important, I thought, as it wasn't a film designed to make a huge amount of money." Clooney sweetened the deal by bringing aboard Julia Roberts and Drew Barrymore to play the important women in Barris' life and added "Ocean's Eleven" pals Brad Pitt and Matt Damon as bachelors on an episode of "The Dating Game," which Barris produced. The gambit worked, to an extent: Clooney got the film made, and the project earned positive reviews, which helped to establish his career as a director on films like "Good Night, and Good Luck." The box office returns, however, were dismal, and barely covered production costs.

Warren Beatty - Ishtar

The 1987 comedy "Ishtar" has achieved that rare place in pop culture history where it has eclipsed its initial status as a colossal failure to beloved misfit status, revered for its willingness to embrace a ridiculous plot, the vain mugging of stars Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, and the (deliberately) atrocious musical numbers. That sea change may be cold comfort for Beatty (who also produced), and even chillier for Elaine May, the comedy legend saddled with directing the film. By nearly all accounts, there was nothing funny about making the film, which was plagued by clashes among May, Beatty, and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, spiraling budget costs, and location shooting in Morocco.

As Peter Biskind detailed in his book "Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America" (via Vanity Fair), the friendship between May and Beatty that led to her directing the film soon unraveled during production, and Beatty complained to Columbia's then-CEO Fay Vincent that May wasn't capable of finishing the picture. When she suggested that he step in, he refused, citing his support of women's rights, and offered a second proposal: Every scene would be shot twice, once by him and once by Beatty, who would then remove May's footage in the editing room.

An absurd solution generated even more absurd end results: Beatty, May, and Hoffman each worked on an edit of the film, sending the budget spiraling to an alleged $51 million (a massive sum in 1987). Word of mouth about the disastrous shoot helped to torpedo "Ishtar" upon arrival at theaters, where it netted just $14.3 million in North America in the wake of a savage critical drubbing.

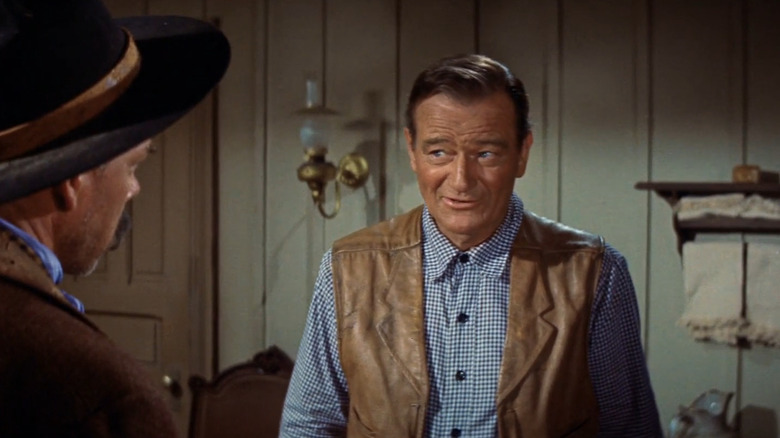

John Wayne - The Comancheros and Big Jake

John Wayne is perhaps best remembered as one of the leading stars of western movies during Hollywood's Golden Age, but the Oscar winner also directed four features. Two of his films — 1960's "The Alamo" and 1968's Vietnam War drama "The Green Berets" — were noted for their fast-and-loose approach to the facts behind those historical events, but Wayne also took over as helmer on two of his films when their directors fell ill.

Wayne had a big hand in shaping his 1961 western "The Comancheros," bringing aboard two longtime friends, George Sherman and Michael Curtiz, to serve as producer and director, respectively. Curtiz had emigrated from Hungary to Hollywood in the 1920s and directed such classics as "Casablanca," which earned him an Oscar. But Curtiz was in poor health — he had cancer, a diagnosis his family and physician had kept from him — and when he was hospitalized after a fall, Wayne took over as director, completing what co-star Stuart Whitman later said was about half the film. Wayne, however, refused to take credit for his work on the completed feature, which would be Curtiz's final credit before his death in 1962.

Wayne faced a similar situation a decade later with 1971's "Big Jake," for which Sherman served as director. Sherman had directed Wayne in B-westerns in the '30s, but by the early 1970s, was working on a sporadic basis, and primarily for television. Like Curtiz, he was also in poor health, which prompted Wayne to again step in as an uncredited director. "Big Jake" was also Sherman's last feature; he died two decades later in 1991.