The Most Expensive Movie Scenes Ever Filmed

Forget the traditional motto; money makes the reel — not the world — go round. Hollywood is a money-making machine, capable of drawing in huge audiences and generating massive profits. In 2019, the North American box office dropped by 4.8 percent over the previous year, but still generated more than $11 billion in revenue. But such alluring entertainment isn't cheap to make — releases from that year include "Avengers: Endgame" and the "Lion King" live-action film, which accumulated costs of $356 million and $260 million, respectively.

With huge competition, each movie needs a unique attraction. All of which requires lots of money and lavish budgets. Naturally, this means the cost-per-minute ratio of feature films can be excessively high. Whether emptying the streets of Times Square, wrecking state-of-the-art sports cars for fun, creating monumental sets, replacing problematic actors or building 300-ton replicas of colossal cruise ships, the movies on this list have invested heavily in certain key scenes. Lasting mere minutes, these sequences have cost millions of dollars, making them the most expensive movie moments ever filmed.

Vanilla Sky's Times Square scene

"Open your eyes ..." "Vanilla Sky" sets the tone of surreal, reality-questioning confusion from the opening scene. Perfectly groomed, grey-hair-plucking playboy millionaire David Aames (Tom Cruise) wakes as Radiohead's "Everything In Its Right Place" aptly lyricizes David's life — immaculate, flawless, perfected. Yet, as David drives his vintage Ferrari through the streets of New York, the first cracks in this illusion appear.

He drives to Times Square, "The Crossroads of the World" with approximately 330,000 daily visitors. It's completely empty, not even the faintest hint of the usual hustle and bustle. David wakes, abruptly. It was all a dream, a false awakening, interpreted by his therapist as a metaphor for loneliness. At only 30 seconds of screentime, the scene provides a fundamental function in the narrative, questioning the nature of reality, and humankind's relationship to dreams.

Surprisingly, no CGI was used. Instead, director Cameron Crowe struck a deal with the NYPD to close off the area between 5AM and 8AM on a Sunday in November of 2000. The result was a spectacular sequence with a spectacular price tag: over $1 million for 30 seconds of footage. Was it worth it? Absolutely. Combining Cruise's enigmatic star power with the desolate backdrop helps to create a poignancy lacking in the 1997 Spanish-language original, "Open Your Eyes"; it would, without a doubt, become the best-remembered visual from the Crowe remake.

I Am Legend's bridge collapse

Will Smith roams the post-apocalyptic streets of New York City as Dr. Robert Neville, a virologist attempting to find a cure for the vampire-producing Krippin Virus. To create the feeling of desperate isolation, Francis Lawrence's "I Am Legend," like "Vanilla Sky," has empty streets to match Warner Bros.' empty wallets. A substantial chunk of its $150 million budget was allocated to a single scene, capturing Neville's tragic separation from his wife and child.

Shown in flashback form as Neville fights loneliness with his canine companion, Samantha, New York City was evacuated and placed under quarantine. In a race against time, his family board a helicopter to escape. Then comes a breathtaking moment of tragedy: the military bomb the Brooklyn Bridge. Amidst the chaos, the blazing bridge collapses into the water below, and Neville's family tragically die in the ensuing accident, sparking the catalyst in his quest for redemption.

A fair share of digital magic was used to capture the missile's impact. Still, the surrounding evacuation was shot on location across six nights, requiring the co-operation of 1,000 extras, 14 different government agencies, an expansive lighting rig and a crew of 250. Increased bureaucracy post-9/11 made acquiring the greenlight on the project a "Sisyphean" task, one costing a cool $5 million.

Spectre's Rome car chase

Think of Bond, and what's the first thing that comes to mind? Aside from a cat-stroking evil genius, cool gadgets, and Bond girls, the answer is more than likely luxurious cars. After all, what would 007 be without an Aston Martin DB5 for company, a car featuring in seven different installments? Snazzy automobiles are largely part of the agent's mythology, and the most recent addition, "Spectre," continued that tradition by placing Daniel Craig in the front seat of the stylish Aston Martin DB10, a car which was never put into production and only exists in that one film (or does it?).

Illustrative of the multi-millions Hollywood has to play with (the budget was rumored to be between $300 and $350 million), production of the 24th Bond set a new record — £24 million ($32 million) of the budget was spent destroying cars. The biggest expenditure came from totaling seven of the ten aforementioned DB10s, a fact that will no doubt cause car enthusiasts to shed a tear. "In Rome, we wrecked millions of pounds' worth," chief stunt coordinator Gary Powell told The Daily Mail.

The DB10 sped through the narrow streets of the Vatican "at top speeds of 110mph" in a cat-and-mouse chase with a henchman in a Jaguar C-X75. A set amount for this singular scene hasn't been confirmed, but the number of destroyed DB10s were "shot one entire night for four seconds of film," making its cost-per-footage ratio astronomically high.

Superman Returns' return to Krypton

Smashing DB10s to smithereens is frugal when compared to Bryan Singer's "Superman Returns." Resurrecting Kal-El onscreen nearly two decades after "Superman IV: The Quest For Peace," one particular scene depicted Superman returning to Krypton. Abstract, atmospheric, and visually striking, the CGI-heavy sequence is intriguing, channeling elements of thoughtful, slow-paced sci-fi. However, that tone is such a stark contrast to the rest of the film — a fun superhero movie — that Warner Bros. chose to cut it out of the final cut.

It was a bold decision, not least from a financial perspective; creating Superman's homeworld cost an estimated $10 million, making it one of the most expensive scenes in history, and most likely the costliest deleted scene ever. At least "Superman Returns" earned favorable reviews, although it failed to capture the imagination of audiences, illustrated by an underwhelming worldwide box office of $391 million. (Maybe that Krypton scene would've helped.)

The Matrix Reloaded's freeway chase

Four years after Neo (Keanu Reeves) swallowed the red pill and unveiled the true nature of reality in "The Matrix," the philosophical cyberpunk sensation returned in 2003 with the second installment in the trilogy. This time, the Wachowskis had over double the budget; safe to say they spent it wisely. Ignoring the adage "don't play with traffic," they rejected digital effects and instead constructed a fake freeway at a disused naval base in Alameda, California.

Stretching a-mile-and-a-half, the set was the backdrop for a white-knuckle chase between Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), The Twins (Neil and Adrian Rayment), and a host of agents. Surprisingly, the Wachowskis also opted for real-life stunts. "They needed to have the best stunt people in the world," Carrie-Anne Moss, who overcame a "major fear" of motorcycles shooting the scene, told IGN. "It was dangerous. You could really feel that everyday that you went out there."

The final result is 20 minutes of mind-blowing, physics-defying carnage — and one of the most memorable car chases in cinematic history. As for the total cost? That had the blue pill treatment, never to be revealed publicly. However, the freeway alone cost $2.5 million. Throw in over one hundred destroyed cars, practical effects and CGI, and a significant percentage of the $150 million budget will have been spent on this single sequence.

Saving Private Ryan's D-Day landing

The six-year Second World War was the deadliest conflict in history, with casualties estimated to be 56.4 million. One of the most bone-chilling, unfathomably brutal battles, the D-Day landing, was the largest seaborne invasion in history. Those who weren't there will never truly know what it was like, yet Steven Spielberg's acclaimed portrayal in 1998's "Saving Private Ryan" put audiences as close to it as they will ever come. Most notable is its depiction of the Allies' arrival on Omaha Beach, a tense sequence Empire Magazine ranked as the "greatest battle" in cinema.

An unforgettable opening 25 minutes depict Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) facing impossible odds, marching through blood-soaked sand, outmaneuvering explosions, and dodging bullets, leading the way for the Allies' eventual victory at the German-occupied shore. It's filmmaking at its finest — realistic, immersive, heartbreaking — and earned Spielberg the Oscar for Best Director. Shot over the course of four weeks, a cast of 750 captured the horror of the fateful day on June 6, 1944.

Unable to shoot at Omaha Beach, Spielberg shot on location on the east coast of Ireland, at Curracloe Strand. With minimal direction in the original script, a testament to the director's skill, most shots were "spur of the moment," unplanned ahead of time. "It helped make things a little more chaotic and unpredictable," Spielberg told DGA Quarterly. Considering the magnitude of the scene and its lasting cultural impact, its $12 million budget represents value for money.

Transformers: The Last Knight's junkyard scene

Michael Bay is renowned for larger-than-life spectacles brimming with huge explosions and bombastic set pieces, epitomized by his live-action "Transformers" franchise. Clearly, there's a thirst for big robots that turn into things, with the series earning a total worldwide box office of $4.48 billion.

"The Last Knight" was the most poorly reviewed in the series, receiving a measly 15 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, but that wasn't due to a lack of investment. Its budget was a whopping $217 million, with a large chunk of that spent on location for one particular scene. As previous "Transformers" installment "Age of Extinction" concluded in a junkyard, producers were keen to maintain continuity. "The (movie's) art director was probably just doing a Google image search for a junkyard," Phoenix film Commissioner Phil Bradstock wryly remarked to Phoenix Business Journal. "And they came across this junkyard just north of the Deer Valley Airport."

Arizona's authorities won't be complaining about the fortuitous Google image search, though — it led to a hefty investment in the area. In rare, detailed insight, Bradstock revealed that over the 10-day shoot, producers hired 40 locals to work behind the scenes, as well as 50 local vendors, and 3,000 cumulative hotel nights. Two months on location equated to an investment of $15 million ... before factoring in CGI and other cost-increasing factors.

Speed 2: Cruise Control's cruise ship crash

The premise of 1994's "Speed" was ingenious: LAPD officer Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves) is tasked with safely disarming a runaway bus, rigged to explode if its travels below 50mph. Traven is assisted by unsuspecting civilian, Annie Porter (Sandra Bullock), who is responsible for keeping the speedometer in the safety zone. Bullock reprised her role for "Speed 2: Cruise Control," contending for the unluckiest movie character in the world award. As Porter enjoys a relaxing break aboard the "Seaborne Legend," fellow passenger John Geiger (Willem Dafoe) hacks the system and programs the ship to collide with an oil rig.

The pièce de résistance of Jan de Bont's sequel is a scene of absolute chaos, as the ship collides destructively into an idyllic, tranquil town on the island of Saint Martin. De Bont wrote the screenplay around the sequence, based upon a recurring nightmare. Its conception rivals "Matrix Reloaded" for practical effects; De Bont "wanted [the scene] to be real for the actors," so production designer Joseph Nemec III oversaw the construction of a 300-tonne replica of the ship, maneuvered via a 1,000-foot track, stretching 60 feet deep into the ocean.

Back in 1997, computer effects were in their infancy and extremely costly. "If we'd shot this all on C.G.I., it would have cost us $500 million," Nemec told The New York Times at the time. Instead, the production team built a replica of two thirds of the cruise ship, while the rest was created digitally by George Lucas' Industrial Light and Magic. That didn't prevent the final scene becoming one of Hollywood's most exorbitant, though. The five-minute scene cost $25 million ($83,000 per second), almost matching the entire $30 million budget of its predecessor.

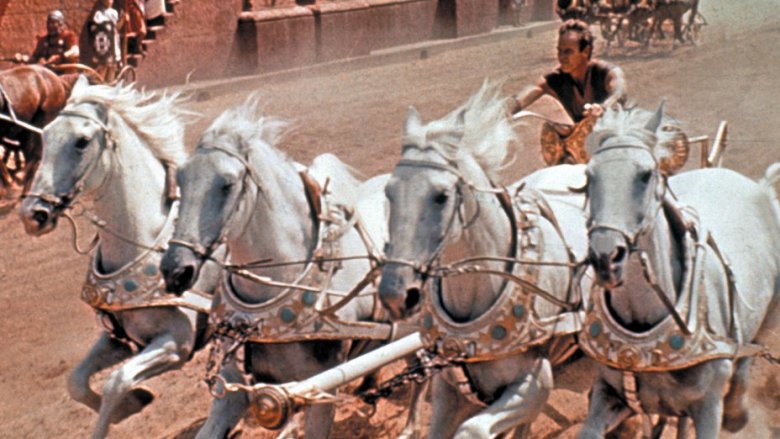

Ben-Hur's Chariot Race

It's almost impossible to imagine the magnitude of the production behind "Ben-Hur." The 1959 adaptation of Lew Wallace's novel, and remake of the 1925 silent film of the same name, is memorable for its extravagance. A stunning nine-minute chariot race is the crux of Wallace's story and William Wyler's feature aptly gravitates around the same centerpiece, underpinning the thrill of the theatrical experience, and highlighting the ability of motion picture to provide audiences with a gateway to another world.

Enduring acclaim is a deserving accomplishment. Following five years of preparation, the production was tireless and demanding, including 300 sets covering 148 acres, nine sound stages, and thousands of extras. Set at Cinceitta Studios in Italy, it was the largest film set of its era. The arena alone — set in the ancient city Antioch — was built by a construction team of 750 workers, created to capture the race between Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and Messala (Stephen Boyd).

Shot over 10 weeks, the singular scene cost $4 million. In today's money that's over $34 million, around $3.7 million for each minute of footage. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer wanted the experience to lure audiences into theatres, though, and it worked. To this day, Ben-Hur is one of the highest-grossing films ever (adjusting for inflation), proving sometimes hefty investment pays off.

War and Peace's Battle of Borodino

Freeways, cruise ships, biblical arenas ... all of the above pale in comparison to Sergei Bondarchuk's faithful adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's 1869 novel, "War and Peace." The four-part, Oscar-winning series was released between 1966 and 1967. It was the most expensive film made in the Soviet Union, costing a whopping $100 million at the time, which is over $700 million in today's money.

The director's biggest challenge was portraying the Battle of Borodino, which took place during Napoleon's invasion of Russia in September 1812. Napoleon's army of 130,000 faced Russia's resistance of 120,000 troops, with around 75,000 casualties in total. Decades away from the type of CGI used to create the "Lord of the Rings" 200,000-heavy scene, Bondarchuk had to rely on practical methods to capture the magnitude of this bloody battle.

The resulting battle scene lasts for an hour, and includes an abundance of pyrotechnics, props, costumes, and over 100,000 Red Army troops, who were drafted in as extras. No amount has ever been revealed for this particular sequence, but divide the total budget by its seven hour runtime, and this hour alone would cost $100 million after inflation.

The Krypton scenes in Superman

Marlon Brando was widely regarded as one of the finest actors of his generation — if not any generation — when he won his second Academy Award for his captivating portrayal of Don Corleone in 1972's "The Godfather." That film was also a blockbuster, and if the producers of the first big-budget "Superman" movie wanted to secure the great Brando to play Superman's father, Jor-El, they were certainly going to have to dig deep and pay up.

Brando ultimately appears in the 1978 "Superman: The Movie" for about 10 minutes out of the film's 143-minute running time. And yet he received top billing, over both Academy Award winner Gene Hackman (as Lex Luthor) and relative newcomer Christopher Reeve (actually portraying the character after whom the film is named). In addition to an appearance fee of $3.7 million, Brando was also contractually obligated to take home 12 percent of the film's profits. The former Godfather's take: $19 million. (In 2020 dollars, that's about $75 million.) And this doesn't even count the expensive-looking Krypton sets that filmmakers had to build for Brando's brief scenes.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor in Pearl Harbor

In 2001, director Michael Bay, at the time best known for "Armageddon," took his penchant for big explosions and dazzling effects shots and applied them to a story set against the backdrop of actual historical events. The result: "Pearl Harbor," an epic action movie that takes place primarily during the events leading up to the Japanese military bombing of the titular U.S. base in Hawaii in 1941. Bay went all out to realistically and graphically depict the bombing of Pearl Harbor, one of the most famous and destructive acts in American history.

This is no computer-generated mayhem and bloodshed — Bay employed practical effects, and a lot of them. The crew employed the use of 700 sticks of dynamite and 4,000 gallons of gasoline to properly blow up six inactive ships from the Navy. It took around a month to set everything up, and the director certainly didn't want to miss anything, so he set up 12 cameras to film it all. In all, this one scene in "Pearl Harbor" (which cost about $140 million to make) ate up approximately $5.5 million.

All the Money in the World

Director Ridley Scott was preparing to release his drama "All the Money in the World" in late 2017 when he was faced with a dilemma: Multiple allegations of sexual misconduct had been levied against actor Kevin Spacey, who played wealthy industrialist J. Paul Getty in the film, which, as Variety noted, had the potential to sink its prospects at the box office and for awards season. With a slated release date of December 22, 2017, Scott made the decision to fire Spacey and not only replace him with Oscar-winning actor Christopher Plummer, but reshoot all of Spacey's scenes with Plummer in the role.

Scott did not enter into the decision lightly; the reshoots carried the potential for exorbitant costs, including fees for not only Plummer but co-stars Michelle Williams and Mark Wahlberg, who would be required to appear in the reshoots. According to Variety, costs for new promotional and advertising material would also require additional fees to rush them to print and screen.

The estimated total for the reshoots, according to Variety, was $10 million, a substantial chunk of the film's $50 million productions costs. "All the Money in the World" ultimately recouped its costs but barely turned a profit; the international box office take was approximately $57 million.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Bad Boys II

In a career built on outrageous action setpieces, director Michael Bay's destruction of a multi-million-dollar mansion in "Bad Boys II" stands out as one of his most astonishing pieces of over-the-top moviemaking, as well as one of the most expensive. The scene concludes the movie with an assault on the palatial home of narcotics dealer Johnny Tapia (Jordi Molia) by Miami detectives Mike Lowery (Will Smith) and Marcus Burnett (Martin Lawrence), as well as dozens of fellow cops and federal agents. The attack results in the total leveling of Tapia's home, in a series of seismic explosions.

Visual effects weren't needed to create the jaw-dropping explosion, because the mansion itself — a 40,000–square-foot oceanfront home in Delray, Florida — was actually destroyed. According to the Tampa Bay Times, the property was initially built for and owned by Coca-Cola heir Michael Bird for $7.3 million. An attempted kidnapping of Bird's son in 1996 caused him to cut ties with the home before it was completed; Boca Raton luxury home builder Mark Pulte then bought the property for $16.5 million, divided it into three parcels, and sold one each to businessman Eric Cherry and industrialist Harold Pontius. The trio agreed that the land was more valuable than the house, so Cherry took out an ad in Variety offering the mansion to a Hollywood production to rent for use as either a location or a prop to destroy. Bay and Sony Pictures took him up on the latter idea.

Thousands of gallons of gasoline and explosives were used to bring down most of the $16.5 million house for the climactic scene in "Bad Boys." The rest was bulldozed after the completion of filming, then replaced with oceanfront homes.

Little Shop of Horrors

Prior to its release in 1986, director Frank Oz's update of the 1960 Roger Corman classic-turned-musical went the route of so many studio movies, with a test screening for an advance audience. According to Oz, the preview audience in San Jose was enthusiastic — up to a point. "For every musical number there was applause, they loved it, it was just fantastic," he told Entertainment Weekly in 2012. "Until we killed our two leads."

The original ending of "Little Shop" echoed the finales of its source material — Corman's 1960 feature — and the Broadway musical, which featured music by Alan Menken and lyrics and book by Howard Ashman (who later collaborated on Disney's "Little Mermaid" and "Beauty and the Beast"). In both versions, the monster plant, Audrey II, devours romantic leads Seymour and Audrey, while the musical infers through a song that Audrey II has the rest of the world slated for its next meal. The Oz movie version takes that scenario to a "Godzilla"-level extreme, with multiple monster plants smashing bridges, devouring trains, and standing triumphant on the Statue of Liberty, impervious to an assault by soldiers milling below it.

Despite stellar puppet and miniature work by Richard Conway, audiences were horrified by the death of Seymour and Audrey, played by Rick Moranis and Ellen Greene. Oz and Ashmun created a new finale where Seymour and Audrey not only defeat Audrey II, but also live happily ever after. The cost of this new end note? Sources vary, with some citing a $1 million price tag, while others note a tally of up to $5 million — either way, a substantial portion of the film's $25 million budget for a single scene.

World War Z

Reshoots are a common occurrence in film production, but in the case of "World War Z," reshoots turned into a total overhaul of the film's final act, sending budget costs skyrocketing. The adaptation of Max Brooks' zombie epic — a joint effort between Paramount Pictures, Skydance Productions, and leading man Brad Pitt's own Plan B Entertainment — drew notices in the entertainment media for an allegedly troubled production and an early edit that Pitt described to USA Today as "atrocious." Reshoots were required, and "Lost" creator Damon Lindelof was called in to rework the entire final third of the script.

With the help of longtime collaborator Drew Goddard, Lindelof added a reported 60 additional pages to the script, which required weeks of reshoots and an additional $20 million expenditure from Paramount. The final tally for bringing "World War Z" to the screen was $190 million — a staggering amount for any production, and according to Deadline, a figure compounded exponentially by the cost of global promotion and Pitt's own share of the box office revenue. "World War Z" eventually netted more than $500 million in worldwide ticket sales, which Deadline claimed allowed the film to "barely break even."

Ghostbusters: Answer the Call

The 2016 "Ghostbusters" (dubbed by the studio "Ghostbusters: Answer the Call" to differentiate from the 1984 classic) had more than its share of problems before, during, and after production, including reshoots that executive producer Dan Aykroyd claimed were upwards of $30 to $40 million (Sony countered the claim in a statement which insisted they were in the neighborhood of $3 to $4 million). But a scene deleted from the original running time generated an inordinate amount of coverage in the press, as well as a reportedly sizable sticker price.

The scene involves Kevin, the Ghostbusters' hapless receptionist, played by Marvel fave Chris Hemsworth. Possessed by the film's main antagonist — Neil Casey's occult Rowan North — Kevin uses his newfound supernatural powers to command an assembled team of NYPD detectives, officers, soldiers, and federal agents to perform in a dance number set to the tune of the Bee Gees' hit "You Should Be Dancing." Though it's an amusing moment and impressively performed by Hemsworth and the actors, Feig told Vulture that the dance number simply didn't work with the rest of the picture. "It was making the rhythm a little too goofy, in a weird way, and it was hurting our story a little bit."

Citing an unnamed source, the Hollywood Reporter reported that it was also an expensive scene, with costs in the low seven figures (Sony again refuted the claim in a comment issued to the Reporter), so its removal would have to have been a major consideration for Feig, the producers, and the studio. Feig said as much in the Vulture interview: "This was the biggest decision of my life," he explained. The solution: Move the scene to the end credits, and add the complete scene to the extended cut of the film on home video.