22 Lightning Fast Facts About Shazam!

With a single magic word, Billy Batson transforms into Shazam: a hero who possesses the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles and the speed of Mercury! It's one of the best premises in the history of superhero comics, and arguably the first major improvement on the archetype pioneered by Superman.

But things haven't always been easy for the superhero known affectionately as the Big Red Cheese. Despite overwhelming popularity in his early days, he was absent from the comics page for over two decades, had difficulty finding an audience when he returned, and had a 77-year journey back to the big screen. From the lawsuit that took him out of comics to his status as one of the most highly anticipated movie heroes of the decade, here's the untold truth behind Captain Ma — er, Shazam!

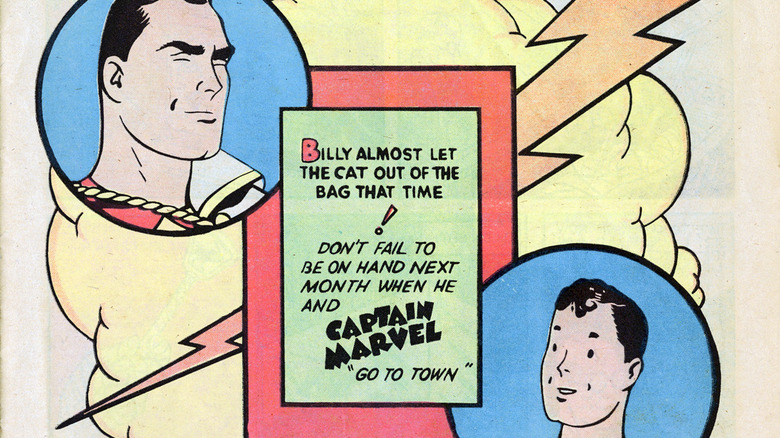

The Golden Age debut of Captain Marvel

We probably don't need to tell you that after his debut in 1938, Superman was a huge success. So successful, in fact, that by the time the '40s rolled around, he had inspired a massive boom for the brand-new superhero genre, including a huge wave of imitators and ripoffs. Dozens of new titles hoped to create the next Superman, and while most of them are justifiably forgotten today, Fawcett Publications was one publisher that actually managed to do it.

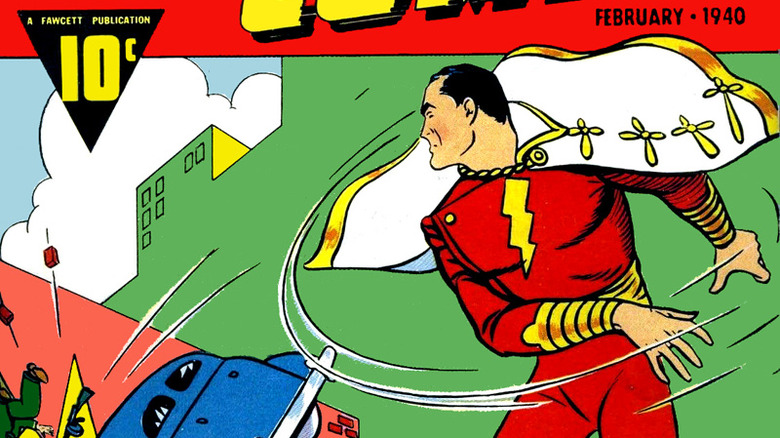

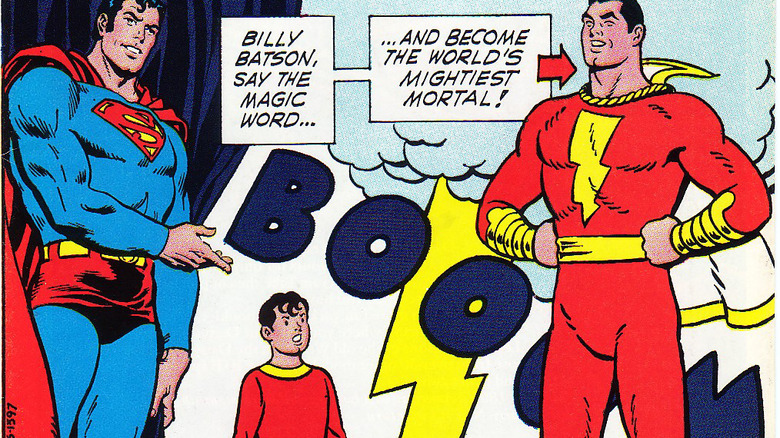

In February of 1940, writer Bill Parker and artist C.C. Beck introduced the world to Captain Marvel, a character who had all of Superman's powers, but with two key differences. First, while Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had rooted their character in sci-fi — and even gone so far as to provide "realistic" explanations for his powers in "Action Comics" #2 by comparing them to the proportionate strength and leaping abilities of grasshoppers and ants — Captain Marvel's origins were drawn from a more magical, mythological source.

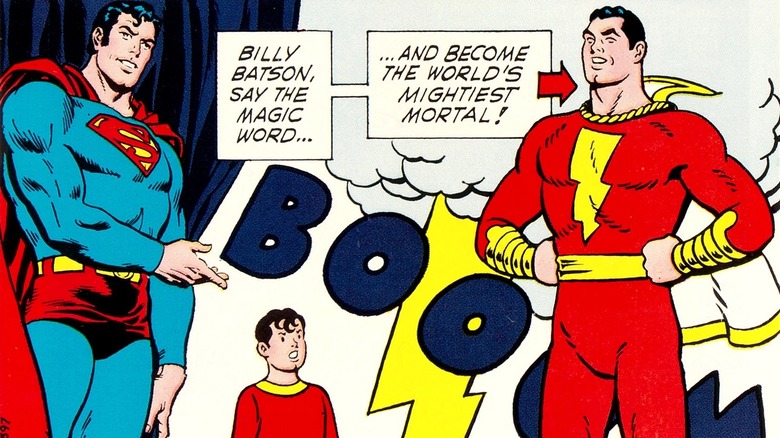

Secondly, and far more importantly, their mild-mannered secret identity was a kid. Billy Batson, a homeless ten-year-old newsboy who'd been cheated out of his inheritance, was chosen by the wizard Shazam. With a single magic word, he could transform into an adult who wielded the powers of six mythological heroes, turning him into the World's Mightiest Mortal.

In other words, every kid who wished they were Superman could now read the adventures of a kid who could become Superman whenever he wanted. With that idea — and beautiful, action-packed artwork from Beck that was genuinely better than anything else on the stands at the time — Captain Marvel was an instant success.

Number One?

If you've got a good memory for trivia, you might already know that Billy Batson and his magical alter-ego made their debuts in the very first issue of "Whiz Comics." Which, of course, was "Whiz Comics" #2.

That might seem confusing, but that's only because it is. Before debuting a new title, publishers would often create "ashcan" editions — cheap, low-quality versions with low print runs that they could use as proof-of-concept to attract potential advertisers and secure a copyright. They'd done the same with Parker and Beck's new character, then called Captain Thunder, but still hadn't settled on a title, publishing it as both "Thrill Comics" and "Flash Comics," a title that was already in use for another hero in a red costume with a lightning bolt on his chest.

By the time they got to publication, they'd decided to go with "Whiz," as a reference to what was then Fawcett's best-known publication: an adult comedy magazine originally meant for a military audience called "Captain Billy's Whiz-Bang." Since they'd already published the story in the ashcan, "Whiz" started at #2 ... even though they'd technically printed it twice already.

It all worked out, though. For reasons unknown, Whiz had two different issues labeled #3, so even if it started with #2, the numbering actually matched up after #4.

Captain Marvel crushes the competition

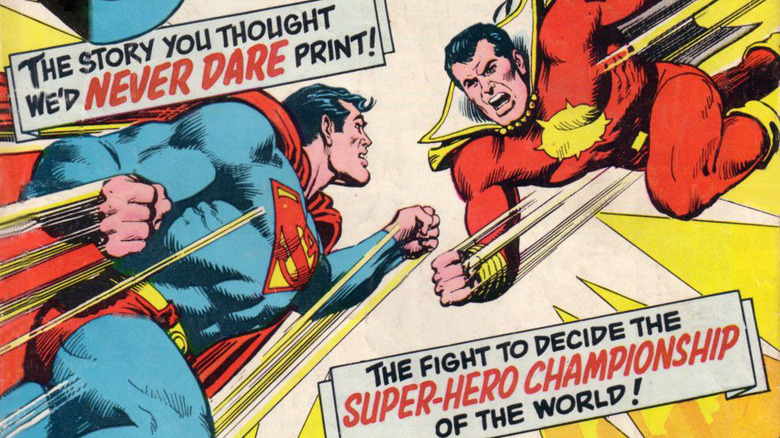

Superman might've been the OG, but as the '40s went on, Captain Marvel quickly became the most popular superhero of the decade by outselling "Superman" and "Action Comics."

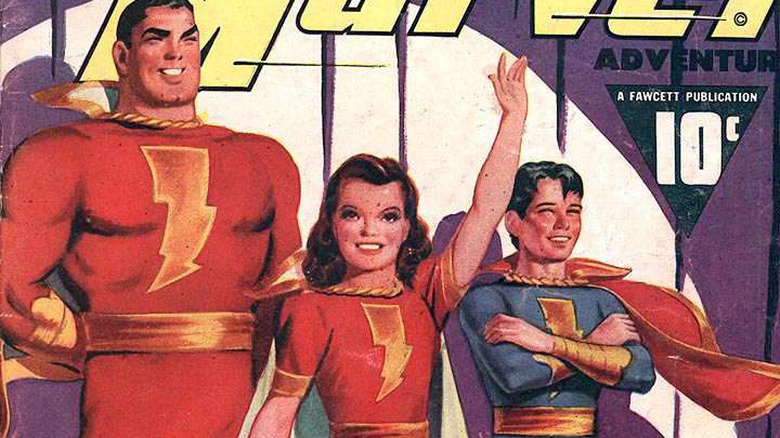

"Captain Marvel Adventures" — a biweekly solo title launched in 1941 that became the flagship of Fawcett's line — eventually hit a high point of 1.3 million sales per month. That's an impressive figure under any circumstances, but consider that over the course of those same years, Captain Marvel and his sidekicks were also appearing in "Whiz Comics," "Wow Comics," "Master Comics," "Captain Marvel Jr.," "Mary Marvel," and "The Marvel Family." In fact, he was so popular that Hoppy the Marvel Bunny, a Bugs Bunny-esque rabbit version of Captain Marvel created for Fawcett's line of funny-animal comics, was headlining not one, but two titles every month.

For comparison, Superman and Batman each had three — and one of them was "World's Finest Comics," the series they appeared in together.

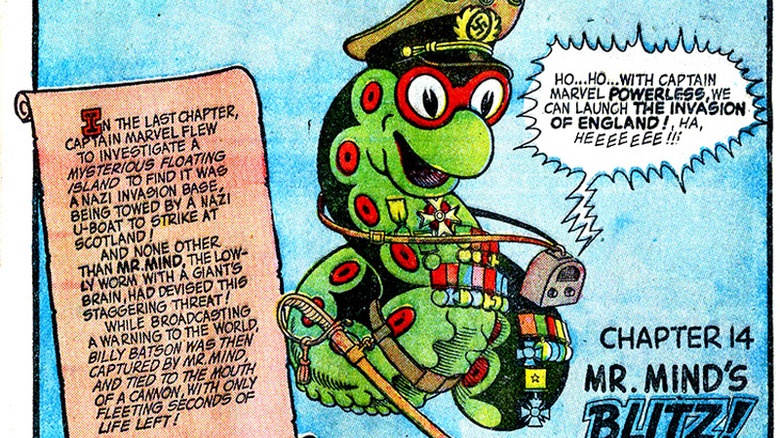

The Monster Society of Evil

If you ever go back and read any comics from the '40s, it's not difficult to figure out the secret of their success: they're actually good. While a lot of Golden Age creators struggled with figuring out the rules of the new medium and the superhero genre, the Captain Marvel stories presented fun, straightforward, and well-constructed adventures. C.C. Beck's art had always been fantastic, and Mac Raboy's art on Captain Marvel Jr. would go on to inspire Elvis Presley's signature style, but the arrival of writer Otto Binder was the final ingredient needed to make Captain Marvel great.

Binder and Beck would become the team most identified with the character, and in 1943, they created what is generally considered to be one of the most important stories of the Golden Age: "The Monster Society of Evil." It was an epic story that ran through a full 25 issues of Captain Marvel Adventures, the first long-form, multi-part superhero story in comics. It was also the first story to feature a villainous super-team made up of pre-existing villains who united to take down the heroes, paving the way for the modern-day event comic and, according to many Golden Age Captain Marvel fans, featuring some of Binder and Beck's best work.

Unfortunately, while Fawcett instituted a "Code of Ethics" for creators that prohibited stories that "indicate ridicule or intolerance of racial groups" in 1942, it's also full of extremely racist elements (via CBR). Japanese people are presented in a particularly negative light, to the point of being drawn with pointed fangs, a common trope in comics published during World War II.

It also features Billy Batson's assistant, a relatively obscure black character named Steamboat who was drawn as a Minstrel Show-style caricature and spoke with an over-the-top "southern" accent, and who wouldn't be dropped from the comics until 1945.

Despite the story's historical significance, those regrettable choices were offensive enough that for decades after acquiring the rights to the character, DC opted to avoid reprinting it, with the only modern version being a limited print run from 1989, published by a different company. In 2018, DC announced plans to collect the saga in a hardcover of their own — but quickly canceled them after a backlash.

Captain Marvel's greatest foe: copyright law

As you might've already guessed, National Comics, the company that would later become DC, was not happy about Captain Marvel outselling Superman. So unhappy, in fact, that they filed a lawsuit against Fawcett that made it to court in 1948, alleging that they'd violated the copyright on Superman by ripping him off wholesale for their own character (via The Irish Times).

Unfortunately for Fawcett, that actually is what happened. In a much later interview, Roscoe Fawcett would recall telling his staff "Give me a Superman," with his only other specification being that his secret identity should be a kid. Even beyond that, the similarities were impossible to ignore.

Superman didn't have the market cornered on super-strength and invulnerability, but Captain Marvel did spend most of his time battling his arch-nemesis, an evil bald scientist, and the cover to "Whiz" #2 featured him tossing a car, much like Superman on the cover of "Action Comics" #1. In 1954, the courts ruled against Fawcett, and they lost the rights to continue publishing Captain Marvel stories.

The spirit of Shazam did live on, though, in a pretty ironic way. After the suit, Otto Binder would take a job at DC and become one of the primary architects of Superman in the Silver Age. Not only did he bring the same kind of stories to Superman that he'd been doing for Captain Marvel, he wound up introducing some of the most famous pieces of the Superman mythos, including the Bottle City of Kandor, and a very Mary Marvel-esque character you might've heard of called Supergirl.

The Lost Years

After the infamous lawsuit, Captain Marvel's adventures ended in 1954, and while he wouldn't be seen on the comics page again for almost two decades, a character that was selling over a million copies a month doesn't just vanish from pop culture. Plenty of readers had fond memories of the Big Red Cheese, and plenty of publishers were eager to recreate that level of success.

In the United Kingdom, a publisher called L. Miller and Son drafted artist Mick Anglo to create an unofficial continuation of the series. The character was renamed Marvelman (with Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel recreated as Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman, respectively), and the magic word was changed to "Kimota."

Since the British printings of "Captain Marvel" had ended at #24, "Marvelman" picked up at #25. It ran from 1954 to 1963, but in 1982, the strip was revived in the pages of "Warrior," where it was rebooted in a much darker direction by Alan Moore and Gary Leach, and served to pave the way for later Moore projects like "Watchmen."

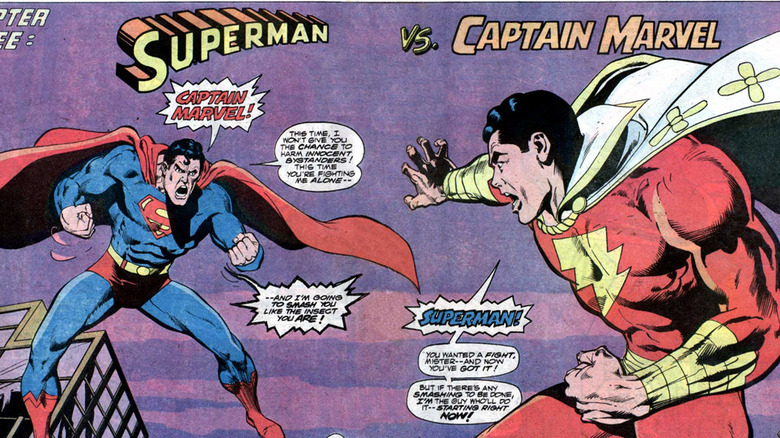

Eventually, readers even got to see a comic book version of the lawsuit when Superman finally took on Captain Marvel in a fight ... sort of. In 1974, a story introduced the Man of Steel to Willie Fawcett, a youngster who could rub his magic belt buckle and say a magic word to transform into Captain Thunder — with the strength of a Tornado, the speed of a Hare, and ... well, you get the idea.

A traveler from another dimension, he fought Superman thanks to the influence of the "Monster League," but was eventually defeated. It's a fun story, but it left many readers disappointed that Superman slugged it out with a knockoff rather than the genuine article. Especially since DC was already publishing a new "Shazam" comic.

The Return of Shazam!

In 1972, DC publisher Carmine Infantino, who had broken into comics as a teenager in the Golden Age, decided that Captain Marvel had been absent long enough. With that, DC licensed the characters from Fawcett, and began publishing all-new adventures of "the original Captain Marvel" in the pages of "Shazam!"

The first issue was drawn by C.C. Beck, and featured Otto Binder — who had left DC in 1969 to focus on sci-fi novels — as a character in the first issue. The series would run for 35 issues, bringing the Marvel Family to a new generation of readers and incorporating them into the DC Multiverse. Readers weren't just reintroduced to the good guys, though. In "Shazam!" #28, E. Nelson Bridwell and Kurt Schaffenberger revived Black Adam, an evil version of Captain Marvel, who had made his only appearance 32 years earlier. While he lost that first fight, he'd go on to become one of DC's most prominent villains — and an occasional hero.

Whatever happened to Captain Marvel?

When DC revived the Big Red Cheese in 1972, it was in a series called "Shazam!," and by 1974, they'd been prohibited from referring to their lead character as "Captain Marvel" on the cover at all. The reason? An upstart superhero publisher had snatched up the copyright on that name for a new character they'd introduced in 1967. It made sense that they would, too. After all, their company was called Marvel Comics.

Their Captain Marvel was a spacefaring soldier of the Kree race named Mar-Vell who had come to Earth on a mission of conquest and decided to become a cosmic hero instead. In an interesting twist, Mar-Vell was revamped in 1969 by Gil Kane and Roy Thomas, a noted fan of the Golden Age in general and Fawcett's Billy Batson in particular. In this new direction, Mar-Vell had a new red costume with a big yellow insignia on the chest and a young sidekick, Rick Jones, with whom he switched bodies in a flash of light whenever a hero was needed. Weirdly enough, nobody ever launched a lawsuit on that one.

Needless to say, the fact that both DC and Marvel were publishing superheroes named "Captain Marvel" — let alone the fact that there would be multiple Captains Marvel at Marvel Comics over the years —caused no end of confusion. Eventually, when the DC Universe was rebooted with the "New 52" in 2011, the name change became official for the character, and Billy Batson's alter ego was rechristened as Shazam.

The Power of Shazam!

When they revived Captain Marvel in the 1970s, DC licensed the character from Fawcett Publications. Over the next 20 years, there would be multiple attempts at reviving the character, including incorporating him into the DC Universe proper — rather than his own setting of "Earth-S" — after "Crisis On Infinite Earths." None of them managed to stick around, though.

In 1991, however, DC made the Shazam Family a permanent part of their universe, acquiring the rights to the character outright. At the same time, veteran creator Jerry Ordway was assigned to reboot the character yet again in the pages of a fully-painted graphic novel called "The Power of Shazam!" In addition to re-telling Billy Batson's origin, this story also tied him more closely to Black Adam, who had his own civilian identity: Theo Adam, a greedy archaeologist who murdered Billy's parents while on a dig.

Released in 1994, "The Power of Shazam" was an unqualified success, and led to the launch of a monthly title of the same name the next year. Ordway wrote and provided covers for the series, and draw a fair bit of it, too. With 48 issues (including a "#1,000,000" special that revealed Billy would take the role of the wizard Shazam in the distant future), it was, and is, the longest-running Shazam series since 1954.

The New 52

After the DC Universe was rebooted for "The New 52," "Shazam" started appearing as a backup story in the pages of "Justice League." In addition to a new costume and a new origin for Dr. Sivana, this version's Billy Batson wasn't quite the wholesome, good-natured kid he'd been in the past. Instead, Geoff Johns and Gary Frank reimagined him as far more bitter and cynical than readers had seen before.

His first act upon meeting the wizard Shazam, for example, was to accuse him of being a child molester, and after getting his powers, he asked a woman for $20 in return for saving her from a mugging. The idea, of course, was that much like Peter Parker, his initial suspicion and self-interest would give way to a genuine heroism and an affection for his adopted family.

There was one other big twist, though. In the pages of "Flashpoint," the universe-ending event that led to the New 52 reboot, readers got a glimpse of a version of Shazam who had split his powers among six kids. This in itself wasn't a completely new idea — Mary Batson and Freddy Freeman had been turned into Mary Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr. the same way, as had a few other characters all the way back in the Golden Age. This time, though, Billy decided to split his powers not just with Mary and Freddy, but with his foster siblings Darla, Pedro, and Eugene.

The result is a whole team of heroes with a much more diverse cast than previous versions of the Shazam Family, who will all be appearing alongside each other in the pages of the next "Shazam" title.

The original plan for Captain Thunder was much closer to the modern Shazamily

Shazam's most recent incarnations in both comics and film have expanded the Marvel Family from the original four to include all six of Billy's foster brothers and sisters. To most fans, this may seem like a radical new twist, but in fact, it goes back to the very oldest version of the character. Who knows? Maybe Fawcett could have avoided all their legal troubles if they'd stuck with this early idea in the first place.

In 1939, Bill Parker's original plan for Captain Marvel was to have a team of six superheroes with one power each, rather than have one kid empowered by six legendary heroes. But his boss, Ralph Daigh, perhaps felt this was too radical of an idea. The first true super team, the Justice Society of America, wouldn't appear until the year's end, and Batman hadn't even teamed up with Robin yet, so Daigh nixed the idea and asked Parker to concentrate all of these powers into one character. It's too bad, since it certainly would have done a lot to distinguish Captain Marvel's adventures from Superman's.

Sorry, that should say Captain Thunder — the hero's name also took a while to hammer into shape. And that goes for the name of the book as well, which may explain why the first issue of "Whiz Comics" says "#2" on the cover. The first issue was an "ashcan" that never left the Fawcett offices and had the name "Flash Comics." But since DC released their own "Flash Comics" #1 at the same time, Fawcett had to pivot. Inspired by their flagship humor magazine "Captain Billy's Whiz-Bang," Fawcett threw together the title for its February 1940 premiere.

Shazam! flew before Superman

The main contention of the DC lawsuit was based on the similarities between Superman and Captain Marvel, and at first glance, it seems undeniable. Here we have two black-haired, square-jawed superhumans flying around in tights, capes, and boots. There was one small problem though: Captain Marvel couldn't have copied the flying from Superman, because Superman had not yet flown when the World's Mightiest Mortal premiered.

Supes' first appearance in "Action Comics" #1 explained his power came from his alien biology, adapted for much higher gravity than earth's. Borrowing a trick from Edgar Rice Burroughs' John Carter of Mars, this meant he could jump around like a grasshopper — but not fly using his own power. Captain Marvel, meanwhile, was flying all over the place as early as his fourth adventure.

While CBR's Brian Cronin finds a few earlier examples of Superman flying in the comics and on the radio, Superman up in the sky wasn't solidified visually until the Fleischer Brothers produced their first animated adaptation over a year after Captain Marvel's first appearance. Even though the cartoons featured the iconic spiel that Superman can "leap tall buildings in a single bound," the Fleischers couldn't find any way to animate it that didn't look silly. So, they got official permission from DC to add flying to Superman's powers, and the rest is history.

Fawcett hated their most popular villain

One of Captain Marvel's secret weapons is his archnemesis. Before Superman had Lex Luthor or Batman had the Joker, Captain Marvel had Dr. Thaddeus Bodog Sivana. It's no wonder the Fawcett crew kept returning to this character — he's just too much fun to leave on the shelf for more than a couple issues at a time.

The ultimate egotist, he never stops insisting he is the rightful ruler of the universe, and even keeps a helpfully labeled throne in his lab. He is no tragic villain — he just plain loves being evil, and his joy is as infectious as his trademark dirty laugh — "Heh heh heh!"

While Dr. Sivana may be beloved by fans, some of the comics' creators weren't so enthusiastic. Released in 1982, "The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics" collected selections of beloved stories with insight from their creators. Speaking about one of Sivana's finest moments in "Captain Marvel Battles the Plot Against the Universe," C.C. Beck offered a surprising description of the mad scientist as "everyone's favorite villain (except Fawcett's; they always thought he was too comical and they would have preferred a more deadly, menacing villain)." It just goes to show that just because a business is successful doesn't mean the bosses know why.

Captain Marvel stood out from nearly everything else on the stands with its skillful combination of action and comedy. Take that away, and you've got, well, just a Superman ripoff.

One writer used a secret signature to prove his involvement in court

In "The Great Comic Book Heroes," Jules Feiffer describes the atmosphere of the comic industry in the '40s: It was a stepping stone on the way to a "real" career. And for many people, it worked — "The Talented Mr. Ripley" author Patricia Highsmith started there, and so did the "Mike Hammer" detective series' novelist Mickey Spillane. Many of the greatest comic book artists of that era like Frank Frazetta and Jack Davis went on to become the greatest commercial illustrators of the next.

"Captain Marvel Adventures" had its own success story with Manley Wade Wellman, who later became a major genre author, combining cosmic horror and Southern Gothic in his stories about rustic monster hunters like John the Balladeer and Judge Purvuisant. But the thing about these future famous authors is that the practice of the time was not to directly credit writers. It's hard to be sure what they even worked on.

As Newsarama reports in their exhaustive oral history of "Shazam!," this became a major issue when Wellman testified in court that his editors asked him to copy "Superman." While typically, Fawcett could have relied on that whole absence of credit thing, which would have meant there wasn't proof that Wellman worked on the comics, he had secretly found his own way to make his mark: Wellman pointed prosecutors to his initials, which he had hidden in word balloons from his stories.

Shazam!'s writer was shocked to learn that comic fandom existed

It took dozens of writers to get new Marvel Family adventures on the stands every week. But one man stands head and shoulders above them all, and that's Otto Binder. He invented most of the supporting cast, and his restless imagination defined the series in its peak years. His work on both Captain Marvel and Superman earned him millions of fans — but it took decades before he even realized it.

"Alter Ego" #147 quotes Binder's reaction to the first fans to reach out to him in 1960: "It just never occurred to me that there could be such a thing as comics fans. ... I just assumed people read the comics, enjoyed them for what they were, and threw them away. I was astounded when Dick Lupoff called me up and invited me to a meeting of comics fans at his house. They all knew Captain Marvel backwards and forwards." To be fair, he wasn't so easy to track down: Ever since his days collaborating on pulp fiction with his brother Earl, he'd used the pen name "Eando Binder," which comes from the combination of their initials, E and O.

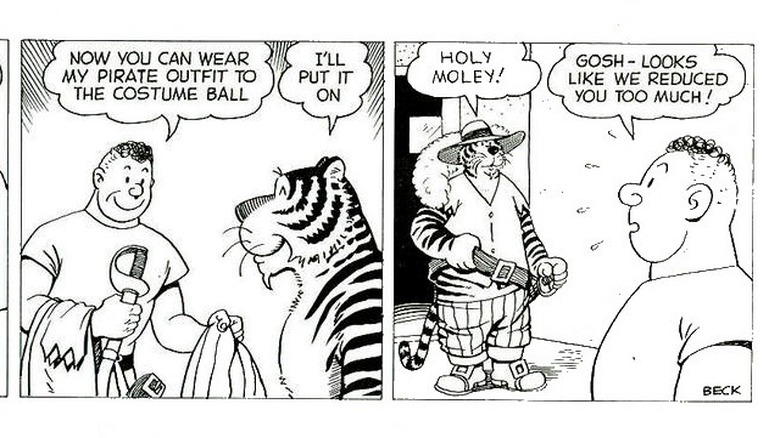

Mister Tawny was being groomed for a newspaper spinoff

"Captain Marvel Adventures" always straddled the action and humor genres, but as superheroes went out of fashion after the end of World War II, the series doubled down. Superheroes were losing market share to crime, horror, and "funny animal" books like "Donald Duck" and "Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies." Fortunately for Fawcett, they'd already marked out a spot in the genre with "Fawcett's Funny Animals," with a cast including Hoppy the Marvel Bunny.

Even more fortunately, the animal upswing coincided with the introduction of one of Captain Marvel's most beloved supporting players: Mister Tawky Tawny. At the height of his popularity, one story in every issue of "Captain Marvel Adventures" was a Captain Marvel adventure in name only, as he took a backseat to the outlandish Tawny's mundane adventures in weight loss and amateur sleuthing.

If it seems like Binder and Beck were setting up Tawny to replace Captain Marvel as their main character, they were. As Fawcett was shuttering its comics department in 1953, Tawny's creators were hoping to land on their feet with a "Mister Tawny" newspaper comic. They chopped up "Mr. Tawny's Diet Dangers" into strip size and replaced Captain Marvel with a new character named Joe.

Unfortunately, they soon found that Tawny was as unfashionable as Cap. By 1953, gag strips were out and soap opera and adventure strips were in, so Mr. Tawny quietly went into hibernation along with his big red pal.

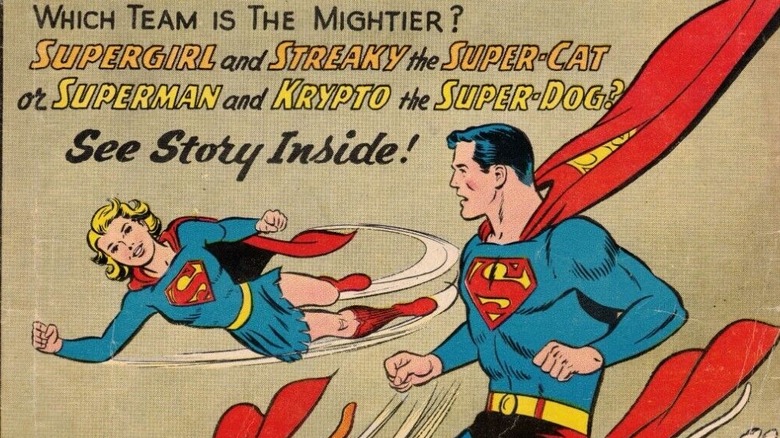

The same man created the Superman and Marvel Families

The great irony of the DC vs. Fawcett lawsuit is that as soon as DC was done arguing that Captain Marvel was too much like Superman, they hired Otto Binder to make Superman more like Captain Marvel. So many of the Superman comics of the '50s and '60s' defining elements — the sharp turns into surrealism, the army of lookalikes, the bizarre transformations — are the same things that defined Captain Marvel in the '40s.

Since Binder couldn't write the Marvel Family any more, he decided to build a new one around Superman, beginning with his introduction of Supergirl in 1959. And he combined his interest in a superhero "family" with his love for whimsical animal characters like Tawky Tawny and Mister Mind, as he expanded Superman and Supergirl's circle with Krypto the Super-Dog, Streaky the Super-Cat, Beppo the Super-Monkey, and Titano the Super-Ape.

He also introduced another (arguably) human Super-family member with the failed clone Bizarro, whose insistence on doing everything backwards was perfect for Binder's absurdist sense of humor. So was red kryptonite, which Binder created as an all-purpose explanation for whatever strange transformation Superman needed to weather that month.

Binder expanded the Superman family beyond his wildest dreams for the Marvel Family with the Legion of Super-Heroes, a team of teen heroes from the future whose membership would eventually extend into the triple digits, and Kandor, a whole city of tiny Supermans bottled up by one of Binder's most enduring creations, Brainiac.

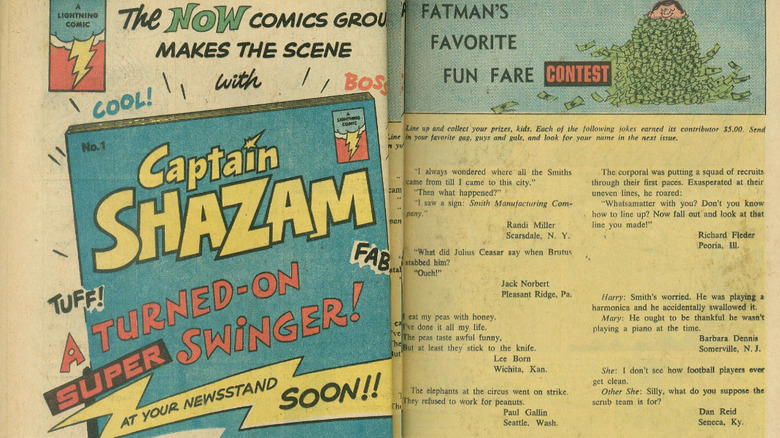

Binder and Beck tried to revive Captain Shazam in the '60s

"Shazam!" spent almost two decades in limbo, but that doesn't mean his creators had forgotten about him. Newsarama reports in their oral history of "Captain Marvel" that Binder and Beck got together with their old editor Wendell Crowley to form Lightning Comics. If that name sounds suspiciously similar to the magic lightning that gave Billy Batson his powers, their first title has even more connections.

"Fatman the Human Flying Saucer" stars Van Crawford, who one ups Billy: He can change into two different superheroes, Fatman and a living UFO, thanks to a friendly alien's chocolate drink. The connection is even more obvious when you see the costume. Fatman could have taken the yellow boots and sash and the gilt-trimmed, high-collared white cape straight out of Captain Marvel's closet. He even has a kid sidekick, who looks suspiciously like Billy Batson.

Their next intended project would have been an even clearer continuation of the trio's past work. They got out ahead of DC's eventual rebranding with "Captain Shazam," but this was a Captain Marvel for the modern age, "a turned-on super-swinger" according to the hilariously '60s-tastic house ad. "Captain Shazam" would also have taken Cap back to his roots in the first Bill Parker proposal: He would have come from the combined powers of six murdered super-secret agents whose initials, of course, spelled out "SHAZAM."

Perhaps predictably, though, "Fatman" didn't set the world on fire the way "Captain Marvel" had. It folded after just three issues, and so did Lightning Comics before readers could ever see what Binder and Beck had in mind for Captain Shazam.

DC started Shazam! to help save Superman

By any name, Captain Marvel is a true hero. If you don't believe us, consider the fact that he was a big enough mensch to pitch in and help the man who ended his career. In the early '70s, DC was beginning to get some of its mojo back from Marvel thanks in no small part to an influx of the competition's talent, including writer Denny O'Neill and artist Neal Adams.

The team saved the floundering "Batman," "Green Arrow," and "Green Lantern" books (those last two getting merged in the process) with an unprecedented willingness to inject real-world darkness into these fantastical characters. Unfortunately, lightning couldn't strike four times: O'Neill attempted similar revamps of Wonder Woman — as a superpower-less secret agent — and Superman.

O'Neill's story "Kryptonite Nevermore" didn't ditch all Superman's powers, but it brought him considerably down to earth after his planet-juggling days of the '60s. At least he got kryptonite immunity as a consolation prize.

The gambit failed, so DC looked elsewhere to make up the losses. "Batman" producer Michael Uslan tells Newsarama that the Superman squeeze led the publisher to strange bedfellows: The same company they'd run out of the comics business 20 years earlier. It was an "I-scratch-your-back" situation: The terms of the court settlement meant Fawcett couldn't publish their own Captain Marvel comics, but nothing was stopping them from making a pretty penny licensing the characters to DC before selling them outright in the '90s to the comic book giant. And who was there to reintroduce Captain Marvel to readers on the first cover? Superman himself. Time (and money) really does heal all wounds.

The original Billy Batson got onto the Shazam! TV show by accident

"The Fawcett Companion" describes Frank Coghlan Jr.'s long and distinguished career that led to playing the screen's first Billy Batson. While Coghlan became indelibly tied to the image of Billy in "The Adventures of Captain Marvel" serial in 1941, he'd gotten started early as a child actor for silent film pioneer D.W. Griffith.

He had a prolific career on-screen from then on, appearing in over 100 projects with legendary stars like Charlie Chaplin and Shirley Temple. And he had a full life outside of acting too, with a career in the Navy that began with flying planes in World War II and lasted almost 25 years.

By then, he was ready to settle down with a nice, quiet job as director of public relations for the Los Angeles Zoo, but he still couldn't escape Billy Batson. One day, a producer from the 1974 "Shazam!" TV show dropped by his office to discuss filming an episode in the zoo. The producer had no idea who Coghlan was, but then he mentioned his past work as Billy Batson. You don't fall backwards into a chance to connect to your series' legacy and leave it alone, and by the time the episode aired, it had a role for Coghlan as the zookeeper.

The DC lawsuit inspired Alan Moore to change comics forever

The DC/Fawcett lawsuit was one of the biggest moments in comics history, even if some of its impact takes a little digging to uncover. It inspired one of the first megahits for "Mad" in "Superduperman!" where Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood reimagined the legal battle as a violent one between Superduperman and Captain Marbles.

After the publishers settled, British publisher L. Miller & Son realized that left them without new Captain Marvel stories to reprint, so they enlisted Mick Anglo to come up with a replacement. "Shazam!" became "Kimota!," Billy Batson became Mickey Moran, and Captain Marvel became Marvelman.

Come the '80s, a maverick young writer named Alan Moore took over "Marvelman" and brought it in a much more adult direction. It was a pattern he continued with future projects like "Watchmen," changing the whole face of the genre on his way. And both were inspired by "Superduperman."

Discovering Kurtzman's work as a child inspired Moore to create a "Mad"-style "Marvelman" parody. That eventually evolved into his published "Marvelman" series, but by then Moore found the implications of infusing reality into comics harder to laugh off. He told George Khoury in "Kimota! The Miracleman Companion" that "It struck me that if you just turn the dial to the same degree in the other direction, by applying real-life logic to a superhero, you could make something that was quite startling, sort of dramatic and powerful" (via Slate).

The same vision led to "Watchmen," with obvious parallels to Superduperman's slovenly, pathetic alter ego Clark Bent in Rorschach and Captain Marbles' sellout turn in Ozymandias.

Alan Moore pitched a dark future for the Marvel Family in Twilight of the Superheroes

Despite his long run on Marvelman, Alan Moore never got to write the original Captain Marvel outside of a one-panel cameo in "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" He did have big plans, though, in his ambitious pitch for "Twilight of the Superheroes." Inspired by "Crisis on Infinite Earths," Moore wanted to make his own universe-spanning mega-crossover. Of course, Moore being Moore, he came up with something much less crowd-pleasing.

"Twilight" takes place in a dystopian near future. American civilization has collapsed, aliens have been banned, and what's left of the country is carved up by "Houses" of superheroes and supervillains. The most influential factions are Superman's House of Steel and Captain Marvel's House of Thunder, who are planning a royal marriage to consolidate power.

It's hard to imagine DC ever being able to touch the World's Mightiest Mortal again if they'd said yes. Just to start with, he's in an incestuous marriage with his sister Mary Marvel. There's also the subplot of the Question investigating a dead body in a brothel, who turns out to be Billy Batson.

Captain Marvel uses his human form of Billy Batson to go incognito in the world and experience it from a less lofty place. But he's still got his adult mind in this young boy's body, so as Billy, he experiments with more mature and risky experiences like S&M. This gives the Martian Manhunter an opening to pose as a call girl, take Billy out, and take his place in the House of Thunder to set the stage for an alien invasion. That's a long way from adventures with gnomes and talking tigers.