Films That Replaced Their Directors And Still Turned Out Great

When it comes to movies, we tend to think of the director as the one in charge, but pretty much every boss has his own bosses to report to, and in the studio system, filmmakers are definitely no different. Directors, even great ones, can be replaced, whether through creative differences, corporate interference, or personal fallout. And sure, sometimes those replacements end up making something forgettable — or even downright lame — but there have definitely been times when a change in directors has benefited the film in question. Just like at any job, there are those wonderful moments in Hollywood when someone new steps in to helm a project — whether they take over in pre-production, walk onto the set, or step into the editing bay — and it all comes together beautifully. With that in mind, here's a look at some of the most memorable movies that switched directors partway through — and still ended up turning out great.

You're gonna need a different director

It seems impossible that anyone but Steven Spielberg could have made Jaws — and technically, in terms of actively shooting the movie, no one else was ever at the helm. That doesn't mean other directors didn't get a shot at the film before Spielberg climbed on board his breakthrough blockbuster, however.

Producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown first turned to Dick Richards, an acclaimed commercial director who'd just broken through to feature films with The Culpepper Cattle Company in 1972. While he might have been their first choice, Zanuck and Brown quickly realized they needed a Plan B after Richards entered talks to direct — whenever he discussed the picture's centerpiece creature, he'd refer to it as a "whale." After correcting their would-be director repeatedly, the producers understandably grew irritated, dismissed Richards, and hired Spielberg. The picture endured a troubled production process that ballooned the film's budget and made the young and relatively untested Spielberg doubt his future as a feature filmmaker, but he weathered those storms, Jaws took a major bite out of the box office, and the rest was history.

Changing size and changing filmmakers

For eight years between 2006 and 2014, Ant-Man was going to be the Edgar Wright Marvel movie. While the Marvel Cinematic Universe expanded and evolved, Wright kept quietly developing his film — until 2014, when after finally entering pre-production on the project, he departed, citing creative differences with the studio.

"I was the writer-director on it and then they wanted to do a draft without me, and having written all my other movies, that's a tough thing to move forward, Wright said. "Suddenly becoming a director for hire on it, you're sort of less emotionally invested and you start to wonder why you're there, really."

Fans were devastated and worried that a potentially unique Marvel project from the director of Shaun of the Dead would now be reduced to a movie essentially made by a committee of producers. Then Peyton Reed (Down with Love) joined the film and reworked it with the help of writer Adam McKay (Anchorman) and star Paul Rudd. Reed's version kept the mentoring relationship between original Ant-Man Hank Pym (Michael Douglas) and new Ant-Man Scott Lang (Rudd), but added elements like the Quantum Realm, which would end up playing a key role in the film's 2018 sequel, Ant-Man and the Wasp. Despite the director change, things worked out for this little corner of the MCU.

Apocalypse Now...in a galaxy far, far away

As with Steven Spielberg and Jaws, it's a hard to imagine Apocalypse Now in the hands of anyone but Francis Ford Coppola. After delivering three masterpieces in The Godfather, The Conversation, and The Godfather Part II, Coppola somehow produced a fourth through Apocalypse Now's "nightmare" production process, and the film remains an essential piece of anti-war cinema. A decade before Coppola's version was released, though, the film almost became something very different.

Back then, the film was called The Psychedelic Soldier, and it was to be directed by...George Lucas. That's right: before Star Wars or American Graffiti, Lucas was going to direct the film from a script by his USC classmate John Milius, and Coppola would serve as producer under the American Zoetrope banner he'd co-founded with Lucas. Lucas planned to shoot the film documentary-style, and he wanted to do it in Vietnam, while the war still raged. Ultimately, Warner Bros. ended its production deal with American Zoetrope, Coppola went on to work on The Godfather to ease the company's financial woes, and The Psychedelic Soldier went into development hell. When it finally re-emerged as Apocalypse Now, Coppola was in the director's chair, and after a journey into darkness, we ended up with a classic.

Fear and Loathing at Hunter S. Thompson's house

The twisted literary sensibilities of a legend like Hunter S. Thompson require the twisted cinematic sensibilities of a filmmaking legend to best adapt them for the screen, and Thompson's iconic book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas ultimately found the perfect match in Terry Gilliam, the Monty Python performer and animator turned feature film director.

Gilliam's Fear and Loathing is a classic, but before he signed on, another cult favorite director almost made his own version. Alex Cox, who helmed Repo Man, was originally hired, and set to work on the screenplay with his wife Tod Davies. Things seemed to be moving along, until Cox and Davies paid a visit to Thompson at his home. That's when the legendary and eccentric writer started to get a bad feeling about the people put in charge of bringing his work to the screen.

Thompson's grievances with Cox included everything from the director's refusal to enjoy American football with him to Cox turning down Thompson's meal of sausage because he was a vegetarian. The real issue, though, was that Thompson didn't like Cox's script. "Here in my house comes this adder, this asp. And he just persisted to insult and soil the best parts of the book," he later said.

Cox and Davies do still wield influence over the final film — they received screenplay credit after a Writer's Guild of America dispute over the film, despite Gilliam's heavy rewrites.

The Four Directors of Oz

Some films change directors once during production and come out the other side feeling muddled and disjointed. The Wizard of Oz, on the other hand, went through three directors and still managed to come out an unassailable classic.

The original director, Richard Thorpe, was fired by producer Mervyn LeRoy because he didn't know how to "think like a kid." Victor Fleming was hired as a replacement, but before he could come on board, George Cukor stepped in to keep shooting going for a week. During his time with the film, Cukor influenced the character of Dorothy (Judy Garland) tremendously, getting rid of her blonde wig, removing some of her makeup, and naturalizing Garland's performance. Fleming then arrived and shot most of the film before heading off to serve as a replacement on another future classic being made that year, Gone with the Wind. In his absence, King Vidor stepped in to shoot the sepia-toned Kansas sequences, including the scene in which Garland sings the film's signature song, "Over the Rainbow." In the end, each director added his own touch, and the result is one of the most beloved movies ever made.

Hacking into the director's chair

Some films change directors during pre-production. With others, the replacement only happens after the studio sees some footage, and WarGames is a case of the latter. Martin Brest (Going in Style) was originally hired to direct the film, and had only been shooting for a matter of days when word came down that the studio was unhappy with his footage. Brest, who'd also clashed with the film's writers over the tone of WarGames, was aiming for pure thriller territory, and missing some of the lightheartedness originally intended for the film. According to the documentary Loading WarGames about the making of the film, Brest took stars Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy for a walk, told them he would be leaving the film, and then was gone. Soon after, John Badham (Saturday Night Fever) joined the production, began working from a new draft of the script from original writers Lawrence Lasker and Walter F. Parkes, and established a sense of fun in the film that endures more than three decades after its release. On his director's commentary for WarGames, Badham noted that some footage shot by Brest is still in the film, including the scene when David visits a pair of hacker friends to consult with them.

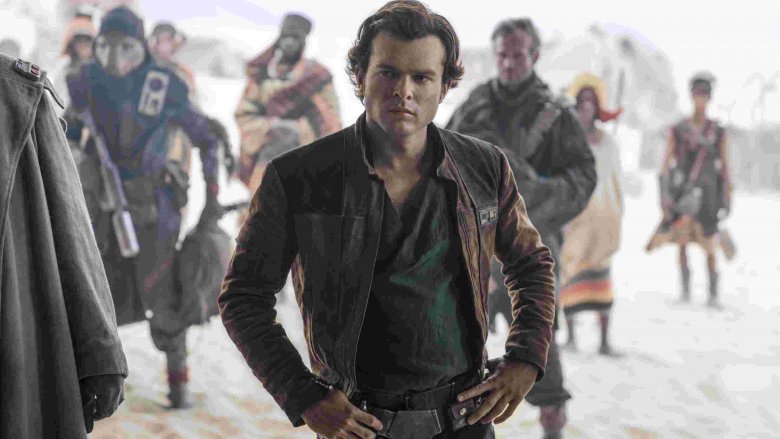

Reshoots: A Star Wars Story

Director replacements, particularly those that take place in the middle of shooting, are never easy, but Solo is a particularly extreme example. Original directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller had been shooting for months when Lucasfilm head Kathleen Kennedy fired them over creative differences in June of 2017. Just days later, Oscar-winning director Ron Howard was brought in to finish the movie — and despite months of work done by Lord and Miller, Howard was tasked with reshooting almost the entire film, so much so that he earned a sole director's credit while Lord and Miller were listed as executive producers. Ultimately, approximately 70 percent of the finished film is Howard's work, including key action sequences and the decision to recast the role of Dryden Vos with Paul Bettany, who replaced Michael K. Williams after the latter was unable to return for reshoots. It's still too early to tell just how kind time will be to Solo. The film underperformed at the box office, but it also managed to gain plenty of staunch defenders and acclaim along the way. However we may see it a decade from now, it's definitely the polished work of a veteran director, and in some ways it's a miracle that it's as cohesive and engaging as it is at all.

Bringing in a reliever to play Moneyball

Moneyball was supposed to be a high-profile collaboration between a major movie star (Brad Pitt) and an Oscar-winning director (Steven Soderbergh) teaming up to tell an unconventional sports story. It seemed to have all the ingredients for success, including Pitt and Soderbergh's experience working together on the Ocean's films, but in June of 2009 everything fell apart. Soderbergh wanted to shoot the film in a documentary style and reworked the script, but executives at Sony didn't see his vision for Moneyball as the version they wanted to make. Citing "honest creative differences," Sony gave Pitt and Soderbergh the chance to shop the film around to other studios. When no one picked it up, Pitt and producer Amy Pascal decided to go to bat for the film again, enlisting Aaron Sorkin to add new scenes to Steven Zaillian's original script; at the urging of his friend Catherine Keener, Pitt asked director Bennett Miller to consider helming the new approach. Miller liked Pitt's idea that the film could be a kind of "Trojan horse" to talk about something more than baseball, and ultimately agreed.

Under Miller's direction, Moneyball became one of the best films of 2011, just two years after it crumbled before the eyes of its producers into something that seemingly couldn't be made at all.

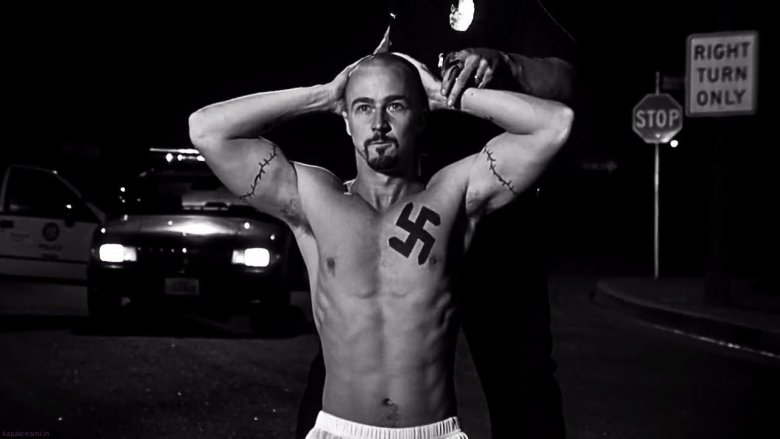

Revisionist American History X

Sometimes, director replacements even happen after filming is finished and the movie is in the editing room. That's the case with American History X, an explosive film with an explosive behind-the-scenes story. Director Tony Kaye, who made his feature debut on the film, claims the shoot went smoothly, but when he turned in a cut that ran just over 90 minutes, things started to go wrong. The studio came back to Kaye with numerous notes — as did star Edward Norton, who Kaye had only begrudgingly hired in the first place.

Writing about the post-production of the film in 2002, Kaye described having a "hissy fit" over those suggestions, to the point that New Line locked him out and essentially made Norton the director in the editing bay. When Kaye did actually get to work on editing, he claimed to find "a whole new film," but New Line never allowed him to complete a new cut. The drama went on beyond the editing bay, to the point that Kaye took out ads denouncing New Line, asked to have the directing credit changed to "Humpty Dumpty," and shut down a Toronto International Film Festival screening of the film. Through it all, American History X remains potent and compelling — on the screen as well as off.