Asteroid City Flips Wes Anderson's Meta Approach & Saves The Film

Long before "The Flash" would attempt to solve the last decade of chaos in Warner Bros.' DCEU, and even before Nick Fury would emerge from the shadows in Iron Man's mansion, there was a cinematic universe arguably more bizarre than any of those populated by superhumans in capes and tights. A universe of muted fantasy, of ordinary people moving through the banality of the extraordinary, and — above all else — a universe of storytellers. This was, and continues to be, the cinematic universe of Wes Anderson.

While films in a shared universe can be connected by plot events or lore (both of which are often changed even slightly to suit the needs of the present story being told), their concrete bonds come down to the characters that inhabit them. Rumblings of Quentin Tarantino's universe began largely with the creation of the Vega brothers, and even before that, Universal brought their horror catalog together when Frankenstein and Dracula met Abbott and Costello.

For Anderson's films, the one enigmatic character that connects the near entirety of his filmography is none other than the director himself.

Though we never see his body, he appears on screen through his unique use of color, his infamous planimetric staging, and the voices of his scripts' idiosyncratic characters — through choices so hyper-stylized and specific, they call unignorable attention to the man who conceived of them. In his films, Anderson is willfully alienated, his vivid specter surrounding and shaping the narrative like a gleefully omniscient puppet master. Yet in "Asteroid City," his new movie within a play about a play he wrote himself, Anderson plunges through several layers of metatext to join his cast and the audience at the center of this strange, intentionally confusing journey.

Wes Anderson is the master of meta

In "The Grand Budapest Hotel," arguably one of Wes Anderson's most conventional, straightforward films, the story is deliberately told through as many layers of perspective as possible. At the innermost narrative circle is Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) and Zero's (Tony Revolori) journey to prove their innocence after a longtime guest (Tilda Swinton) is murdered for the estate she leaves behind. As we witness it unfolding, the tale is told, 30 years later, by an older Zero (F. Murray Abraham) to a vacationing novelist (Jude Law); this is framed by that very novelist, decades later (now played by Tom Wilkinson), recording his account of how the story came to be — which is shown to the audience through the memory of a young girl visiting his grave with her own, cherished copy of "The Grand Budapest Hotel."

Similar narrative framing devices can be seen throughout Anderson's filmography. "Rushmore" and "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou" both feature variations on the play-within-a-play metatrope. "The Grand Budapest Hotel," "The French Dispatch," and "The Royal Tenenbaums" are all presented through meta-media that doesn't actually exist. And even when Anderson adapted someone else's story in "Fantastic Mr. Fox," he included a shot of the source material with the author's name and the title of the story clearly visible. There is no verisimilitude in the "Wes Anderson Universe." You're watching a movie, something that someone created — and he really doesn't want you to forget that.

An uncharitable viewer may dismiss these choices as egocentric, and there are admittedly moments in his films that ultimately separate the audience from the heart of the story being told. That is certainly the case for the first two acts of "Asteroid City" — until Anderson upends his tools of separation to enter the story himself.

Asteroid City's cast feel like storytellers of their own lives

Unlike his previous films — which use metatext mostly to question who tells these stories within stories, as well as why they're being told — "Asteroid City" endeavors to question why we engage with them at all.

The various characters of "Asteroid City" are — in their own ways — all of Anderson's ilk, which is to say they have a complete, confident understanding of the world. The children and teachers process it through academic study. The parents (including Tom Hank's Stanley Zak) filter it through their maturity and years of life experience. The three young witches weave it through their fully held (and admittedly unorthodox) religious beliefs. And Augie (Jason Schwartzman) and Midge (Scarlett Johansson) — perhaps most similarly to Anderson — turn it into art they can capture, contain, and dissect.

As they enter the story, they use these various strategies to create personal perceptions of a world that's every bit as intentional, organized, and understandable as the shots Anderson creates for them. Then, an alien played by Jeff Goldblum shows up to ruin everything.

By proving the existence of extraterrestrial life, the alien in Asteroid City changes the rules

The alien doesn't start killing humans or trying to communicate with them when it arrives. Sure, it takes something from the picturesque crater, but that bit of space rock isn't the most important thing it leaves with — rather, the alien's true theft is that it takes away the ensemble's sense of certainty about the world.

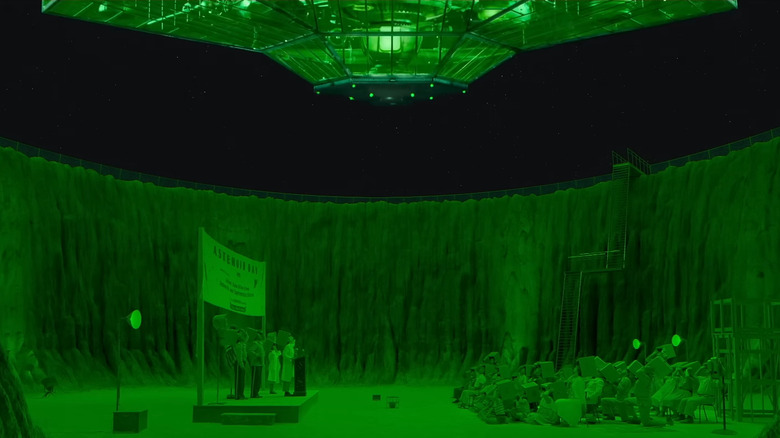

Suddenly, every disparate belief held by the cast is simultaneously upended by one moment, sparking a creeping sense of nihilism that spirals out of the film's central narrative into the outer edges of its meta-story. At the film's climax, in which the actor that plays Augie stakes his sanity on an attempt to "understand" an illogical moment in the fictional play "Asteroid City," it can't help but feel as though Anderson is descending from his own saucer-like plane of creativity to share something rarely vulnerable.

The actor's frantic search for meaning brings in blatant autobiographical tones that haven't been nearly as present in Anderson's work since "Rushmore." It's a scene so surprising in its impact that it manages to retroactively elevate a film that often felt aimless. For the majority of its runtime, audience members may feel as though they're pressing through the plot without any idea of what they're moving toward, a feeling almost identical to what the actor and Anderson are trying to process quietly throughout the story.

In Asteroid City, none of us have the answers -- not even the director

A psychologically nihilistic resolution like the one found in Anderson's new film risks appearing as confusing or pretentious. Given the fact that you arguably need to see "Asteroid City" twice to appreciate one of its central ideas may even count as a failure to some audience members. But it must be acknowledged that Anderson (a celebrated director who could easily coast on an unparalleled career) attempted to interrogate his own style in order to offer even his longtime fans a fresh idea — something intentionally and ambitiously unsure of itself.

In "Asteroid City," Wes Anderson proves that he can surrender himself into the audience as easily as he can separate himself from them as a director. It's a refreshing perspective coming from someone as meticulous as he, and it has the potential to evolve this film from a passingly amusing yet meandering stroll through a strange, fictional moment in time into a timely mediation on what we do when all our tools for understanding are taken from us.

Anderson is surely conscious that his audience has lived through a once-in-a-century pandemic; that they continue to see the growing threat of an ignored climate crisis; that they've witnessed a rise in political and social unrest as well as the first seeds of a culture potentially altered by technology moving faster than most can comprehend. Perhaps in all this chaos, cinema's most certain auteur wanted to comfort his audience with something universally uncertain, which offers the idea that — in life and in art — the attempt to make meaning is sometimes more human than meaning itself.