Classic Movie Tropes That Are Horrifying Today

As our society evolves, the artifacts of the past become more noticeably dated, reflecting values and standards that are no longer the norm. Movies are a great example — the art form of narrative film is now more than a century old, leaving us with a long history of movies that were completely mainstream in their time but seem weirdly out of place today. As modern audiences continue to have complicated arguments over the kinds of content that we find acceptable in films, it can be instructive to look back at the past and see how many storytelling elements and character archetypes that were once common and viewed as normal have become glaring in contrast to the standards of today. With that spirit of edification in mind, here are some tropes that were quite common in classic films but modern audiences would find horrifying in their backwardness today.

Blackface

In the early 20th century, when black Americans were still openly oppressed by Jim Crow laws that mandated segregation, it was common practice for white performers to paint their skin black and perform styles of music — and act out stereotypes — that were associated with black culture. This practice, called blackface minstrelsy, had been popular since before the Civil War. It was a key part of early cinema, including the unsettlingly pro-KKK film Birth of a Nation. Perhaps the most famous example, however, was also the first feature film with synchronized sound: 1927's The Jazz Singer, in which Al Jolson plays a white Jewish man who pursues a career as a blackface minstrel singer. Despite the film's historical importance and Jolson's considerable talent, the pervasive use of blackface makes it extremely hard to watch for modern viewers who have a clearer understanding of how minstrel performers contributed to negative stereotypes of real African-American people.

Blackface has never fully gone away. Spike Lee used it extensively to make a point about ongoing racism in the entertainment industry in his 2000 joint Bamboozled, while the 2003 Bob Dylan film Masked and Anonymous put Ed Harris in blackface for reasons that were harder to understand. In general, however, any use of the practice in recent films will contain at least some acknowledgment that it's offensive, whereas older films often don't.

Cowboys vs Indians

Fights between white 19th century settlers of the American West and the indigenous native populations of the land were a central part of mid-20th century popular culture. Battles between cowboys and Indians weren't just a constant feature of Western movies and TV shows, they became a common source of play among young boys, whether through the use of small plastic figurines or just by chasing each other around with toy guns and bows. The problem with these stories is that the Native American characters are often portrayed as unthinking barbarians, or even an undifferentiated mob. The fact that they're most likely attacking the white people because those people have invaded their land and claimed it for themselves is generally glossed over. Even in a film like The Searchers, which presents the anti-Indian racism of John Wayne's character as a major flaw, the portrayal of the Native Americans in the movie still lacks nuance, and one woman in particular, who marries Jeffrey Hunter's character without him realizing it, is humiliated as nothing but comic relief.

The "Noble Savage"

On the other hand, sometimes older films try to portray Native Americans in a positive light, but that doesn't usually go much better. The result is often a stoic character lacking recognizable human emotions, who sometimes spouts clichéd "wisdom" and often exists to bring aid to white protagonists. Tonto, the Lone Ranger's sidekick, is probably the ultimate example of such a character. They're also common in more films of the last 30 years, such as Dances with Wolves and Last of the Mohicans.

Native Americans aren't the only population who are all too often portrayed as noble savages. Africans (The Gods Must Be Crazy), Aboriginal Australians (Walkabout), and basically any other group that white people has historically regarded as uncivilized can fall victim to the trope. Even space aliens in sci-fi movies, like the Na'vi in James Cameron's Avatar, often fall all too easily into the stereotype of the noble savage.

Grown men romancing teenage girls

Vincente Minelli's 1958 musical film Gigi begins with a 70ish Maurice Chevalier singing "Thank Heaven for Little Girls." The song fits, because the entire film is about the special appeal of the title character, a teenage courtesan in training, and how she excites an adult bachelor who's bored with his long string of adult female partners. In the past it was more common for men to have relationships with significantly younger women. Since women weren't commonly regarded as equal partners at any age, there was no expectation of equality. It's not surprising, then, that adult men dating surprisingly young and sometimes even underage women is far more normalized in old movies.

One of the most egregious examples is Woody Allen's 1979 film Manhattan, in which the 42-year-old character played by Allen is dating a 17-year-old Mariel Hemingway. Although the bulk of the film deals with him leaving her and attempting a relationship with a more age-appropriate woman (never mind that Diane Keaton, who played that part, was still a decade younger than Woody Allen), he ultimately runs back to the teenage girl at the end of the film, telling her how pure and perfect she is. There's simply no way around it — it's creepy.

Gay people being turned straight by the right partner

These days, a lot of people who watch Kevin Smith's Chasing Amy understand Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams) as a bisexual woman, but that's not actually the way the 1997 film presents her. When she meets the male lead, Holden McNeil (Ben Affleck), Alyssa is very clearly identified as a lesbian with no interest in men. It's only when Holden manages to be exceedingly charming that Alyssa eventually gives in and has a romantic and sexual relationship with him. The plot later reveals that she had previous sexual encounters with men in her youth, but the idea of bisexuality is still never discussed. The film's preferred idea is that she came out as a lesbian after unsatisfying experiences with men, but a guy as great as Holden is able to make her reconsider her sexuality. It's not a great message to send to men about lesbians they may encounter in their own lives.

Of course, the relationship in Chasing Amy is far less offensive than many similar encounters in earlier movies. In Goldfinger, James Bond converts the absurdly named lesbian Pussy Galore into his latest girlfriend by assaulting her in a barn.

When it comes to gay male characters, the conversion tends to be less simple. Some films based on the works of Tennessee Williams, such as Suddenly Last Summer and Cat On a Hot Tin Roof, feature men torn between their gay desires and their beautiful wives. Even in those instances, their sexuality is treated like a failure of will rather than a fundamental aspect of their identity.

Gender-bending as evil or laughable

From Milton Berle to Some Like It Hot to Monty Python, a lot of old comedy is built around the idea that there's nothing funnier than a man in a dress. Films like Tootsie and Mrs. Doubtfire are all about finding complicated reasons why a man has to pass himself off as a woman, and then embarrassing that man when the truth is revealed. From today's perspective, the problem with stories like these is not just that they can be inadvertently quite insulting to transgender people, it's that the humor to be found in men dressing as women is often dependent on the idea that he's lowering himself to do so, thus implying that women are essentially inferior to men.

There are other films, often by LGBTQ filmmakers, that treat crossdressing and gender-nonconformity with more nuance, such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Hedwig and the Angry Inch. Unfortunately, even films like these sometimes fall into the same tired old tropes of drag as a source of embarrassment and ridiculousness, but there still tends to be a lot more nuance along the way.

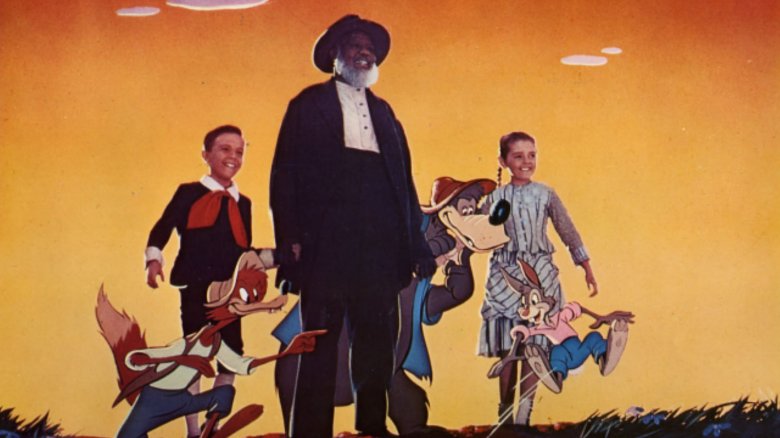

Doting and helpful black servants

Slavery is one of the absolute worst aspects of American history, and plenty of films, like Twelve Years a Slave, portray it that way. However, a lot of older films gloss over the horrific aspects of slavery in favor of smiling black servants who want nothing more than to take care of white children and their sometimes equally needy parents. Hattie McDaniel was a talented black actress who was pigeonholed into playing several such roles. Most notably she played the tellingly named Mammy in Gone with the Wind. She played a similar role in Disney's Song of the South, opposite James Baskett as Uncle Remus, a grinning gray-bearded black man who sings the extraordinarily upbeat "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" while cartoon animals frolic around him. Although Song of the South actually takes place after the Civil War and the outlawing of slavery, the distinction isn't always clear to viewers. Just like McDaniel's Mammy remained with Scarlett O'Hara after the end of slavery, the black characters in Song of the South still live on and around the plantation, seemingly lacking other ideas about where to go and what to do.

Mob justice portrayed in a positive light

Sometimes, particularly in Westerns, you have to get a posse together. Sometimes law enforcement can't be trusted, or simply doesn't exist if you're too far from civilization, and the people have to rise up to make their own justice. Sometimes there's nothing to do except shoot the bad guy yourself, or hang him in front of the entire town. In old movies this often works just fine. It's obvious who's guilty, and the people can judge for themselves what justice must be handed out. Unfortunately, in real life, an angry mob almost never leads to justice. It usually leads to the persecution, or even death, of someone who's an easy target due to class prejudices or racism. The romanticization of mob justice in Westerns and elsewhere only makes this problem worse, because it leaves people with the impression that the mob knows what it's doing.

A similar problem exists with movies about singular vigilantes, whether it's Death Wish or even some versions of Batman and the like. The portrayal of criminals in vigilante movies often reinforces the prejudices of the day, such as in Peppermint, in which a nice white lady avenges her family and protects the local community by killing evil Mexican criminals.

Men Spanking Women

If you've ever seen the 1963 John Wayne film McClintock!, you certainly remember the scene in which Wayne as the title character spanks his ex-wife, played by Maureen O'Hara. It's not just a memorable scene in that movie, it's the image used on the original poster and most other promotional art for the movie. Ten years earlier, the musical Kiss Me Kate also featured a man spanking the title character on the poster. Another John Wayne film, 1968's True Grit, also features a spanking, but this time it's Glenn Campbell who spanks young Kim Darby, and Wayne tells him to stop because he's "enjoying it too much."

No matter how sexual you think all of this spanking was meant to be, its certainly not respectful towards the women it happens to, or towards women in general. It promotes the same idea of women as infantilized and fundamentally beneath men that makes huge age differences seem normal and treats dressing like a woman as fundamentally shameful.

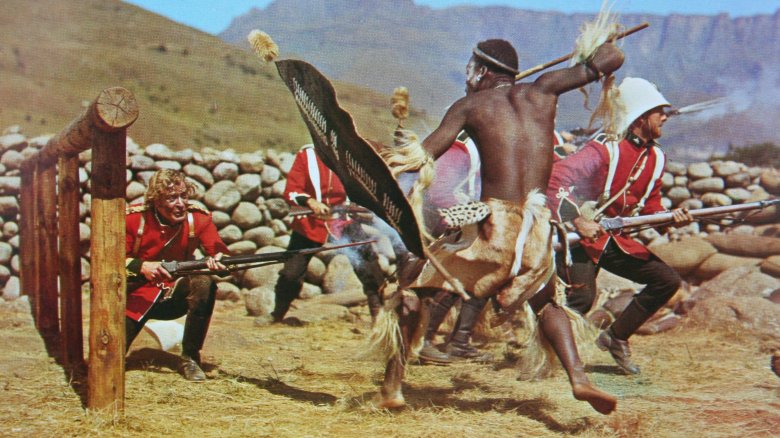

Colonial heroes

The heroic colonialist is a part of many cowboy and Indian stories, but it's much bigger than that. There's a long history of the white men who invaded other people's countries being treated as heroic for doing so. Take the 1964 British film Zulu, for example. It's all about the heroism of a small group of British soldiers who must defend themselves against thousands of African Zulu warriors. The Zulu army is treated as an invading force, which becomes a bit bizarre when you realize that the movie takes place in Africa. This is Zulu territory, and the British are only there to take it away from them and claim it for their own.

It's hard not to notice the unifying factor of all of these tropes — it used to be far more acceptable, in movies and elsewhere, to ignore the needs and concerns of whole swaths of humanity. People of color, women, and LGBT people were all portrayed in movies in ways that unconsciously reflected their oppression and prioritized the viewpoints of straight white male protagonists. This is a problem that hasn't entirely been conquered, and in fact continues to be the subject of arguments, but enough progress has occurred that the tropes of decades past have begun to look as ignorant as they really always were.