The Most Embarrassing CGI Moments In The Flash

Contains spoilers for "The Flash"

"The Flash" might be the speediest of DC Comics' superhero characters, but it certainly took its time getting a Barry Allen solo film to the big screen. Warner Bros. had been toying with the idea since the 1980s, and the DCEU's version took nearly a decade to come to fruition. All that time could've been an indication that the studio and ever-changing creative team were doing what they needed to do to get "The Flash" just right. Prolonged development limbo can, however, also be a sign that a production is doomed from the start. Early buzz out of CinemaCon — particularly the vocal opinions of Warner Bros. Discovery head honcho David Zaslav and recently appointed steerer of the DC ship, James Gunn — made it seem like the movie was worth the wait. Then, real critics' and audience reactions began to hit the internet, and while they weren't roundly negative, folks didn't agree that "The Flash" was the best superhero movie ever made.

Unfortunately, what everyone can agree on is that the computer-generated visual effects in "The Flash" are some of the worst in recent memory. Even the kindest reviews single out the poor state of the CGI. Director Andy Muschietti attempted to explain the film's appearance by suggesting to Gizmodo that it's all by design. Various people have been trying to make "The Flash" in earnest since roughly 2004, but that's no excuse for the graphics of a tentpole movie with a budget north of $200 million to look like they come from the early 2000s. These are the most embarrassing examples.

Running

In truth, there are only so many ways a hero can be super. One of these is the ability to run really, really fast. While there are dozens of speedsters in DC and Marvel canon alone, two of the most famous are Quicksilver and Flash. Super speed is a cool and useful power, but it's a difficult one to depict on screen. To make the point that someone like Barry Allen can accomplish a minute's worth of tasks in a millisecond, a movie basically has to show the opposite of what's really going on. The action slows down almost to a freeze so that the audience can catch everything that's going on.

We can't blame Muschietti for continuing a longstanding visual tradition with these Flash-in-action scenes. The problem is, reverse speed sequences have been done before, to much more impressive effect. One standout example is the scene in which Evan Peters' Quicksilver saves Magneto and Professor X in "X-Men: Days of Future Past." Ezra Miller's Flash has been deployed as an effective visual in the DCEU already, but a film that's wholly about the character should've featured the best fast-running set pieces yet. Instead, Barry Allen looks like a cartoon, both when he's shown in full speed-of-light sprint and when events play out in slow-motion. The most memorable running moment is the gag when Barry jogs at a normal pace and realizes he's lost his powers.

Planes and spaceships

The Flash is so efficient on foot, he doesn't need a ride to get from point A to point B, as we see in the opening sequence in which he travels from Central City to Gotham City in less than half the time it takes to make a breakfast sandwich. But Batman does, as do aliens seeking to terraform Earth, so "The Flash" includes its fair share of souped-up and otherworldly modes of transportation. To be fair, Ben Affleck's Batcycle and his daytime chase through the crowded streets of Gotham are believable enough. The same can't be said about the vehicles that take to the air.

These elements often look so disconnected from the rest of the frame that they almost read like stickers. Planes and spaceships — even digitally rendered ones — weigh many tons and should have an effect on their passengers and surroundings. But when Affleck's Batplane hovers over city blocks or when Michael Keaton's Batplane enters the snowy atmosphere of Siberia, there's an uncanny weightlessness and ease to their movement, even if animators put the shadows in the correct places. The aerial combat in the final battle feels especially cut-and-paste. And, to go along with the slight but noticeable lack of realism, there's also a slight lack of design interest. These aren't the ugliest transports ever to appear in a superhero movie, but they aren't anything special.

Falling into the abyss

When alternate Barry Allen, newly imbued with Speed Force powers, first enters the Batcave, he quips that he nearly fell to his death into an abyss. Characters go on to tumble downward multiple times in the second half of "The Flash," and in every instance, the effect is that of a video game character missing a jump and wasting a life. During the scene in which the two Barrys and Bruce Wayne try to break who they think is Superman out of a top-secret Russian facility, our heroes descend (and ascend) through various shafts and tunnels. The spaces themselves are illustrated as poorly as the action. Bodies and backgrounds are a blur until Flash or Batman land with a heroic thud, at which point it's clear an actor is taking over for the pixels.

In subsequent battles, characters fly, eject themselves from planes, or dive to the surface of the Earth. But Flash, alternate Flash, Batman, and Supergirl never really feel like part of their environment and as a result, the audience gets no rush from what should be exciting moments. The only passable fights take place firmly on the ground, like when the two Barrys take on an unkempt Bruce Wayne in his kitchen (and even that scene has some sketchy CGI flourishes). We don't know to what extent VFX (or doubles) were used to enhance the physical prowess of the 71-year-old Keaton (most of his stunts are fine-to-good), but that scrappy scuffle feels of more consequence than anything else in the movie.

Grappling hooks

As we learn from Keaton's Bruce Wayne thanks to a metaphorical bowl of spaghetti, there are certain inevitable intersections that connect the multiverse. That Batmen have (or at least had) Alfreds is one of them. Another appears to be the Dark Knight's affinity for grappling hooks. Ben Affleck's Batman uses one to apprehend the terrorist bank thieves and save the day in the opening scene, and Keaton's Batman is outfitted with one later in the film. His lookalike toy even comes with a grappling hook gun.

But what's cool on an action figure isn't always as cool in live-action ... or at least in VFX animation that's meant to pass for live-action. Any time a Batman is suspended from a grappling hook's line in "The Flash," the image quality of the black cowled and caped figure immediately reduces to that of a Y2K era blockbuster whenever filmmakers had to render something that couldn't be performed as a practical effect. The way Affleck's and Keaton's bodies move eerily smoothly through the air calls to mind, say, the worst shots of Harry Potter on a broomstick. If you're going to have not one but two (and arguably four) Batmen in your Flash movie, you'd better make sure you do justice to one of his most essential accessories.

Zod's face

Michael Shannon is one of a mind-boggling number of actors who reprise their superhero roles in "The Flash." Shannon played Superman's nemesis, General Zod, in Zack Snyder's "Man of Steel." His character dies at the end of that film, but Zod is back in the alternate timeline that comes to be when Barry places that can of tomatoes in his mother's shopping cart. It seems Shannon had a better experience playing the villain the first time around. "I'm not gonna lie, it wasn't quite satisfying for me, as an actor," he told Collider. "These multiverse movies are like somebody playing with action figures."

Though played by an actual human, Zod's design was heavily reliant on CGI in "Man of Steel." The 2013 Superman origin story received mixed reviews overall but general praise for its use of Zod's armored suit and fighting style. 10 years later, the rogue Kryptonian is as much of an afterthought visually as he is narratively. Shannon lamented that Zod is used as a mere obstacle rather than a true supervillain in "The Flash." His costume and his movement (as video game-y as two Flashes falling down an abyss) reflect that. But the most egregious thing about this alternate Zod, 10 years in the making, is his face. On occasion, Shannon appears to be completely rendered in CGI. It's bad when Supergirl is landing a punch, but it's worse when Zod is just standing there, staring. These shots read just as artificial as the hastily rendered action.

Worlds collide

"The Flash" isn't the first movie to try to visualize the multiverse. In the last year or so alone, there have been at least four major multiverse releases, including this year's Academy Award winner for best picture. While "Everything Everywhere All at Once" settled on mid-budget editing tricks and a bagel, and Marvel usually represents diverging realities with a blue branching timeline in everything from "Loki" to "Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse," Keaton's Batman crosses two dry pieces of spaghetti to explain how the butterfly effect changes the past and the future. That's a great use of an extremely low-cost prop. Less great is what audiences see, as the tagline for "The Flash" promises, worlds actually collide.

In the wake of the climactic battle, when Dark Flash (who we learn is actually alternate Flash) refuses to stop trying to change the outcome, giant colored orbs begin to crash into each other and tear apart what Prime Flash calls the "fabric of everything." These orbs contain images and brief video clips of DC Comic characters through the ages, and they vaguely resemble a cross between an infographic and a bunch of film cells. Not only is their form unexplored, their aesthetic feels much more like a fan service delivery system rather than the impending end of infinite worlds. The Crayola-colored spheres of existence cap off a disappointing third act in which the story and the special effects start to feel as though the creative team ran out of time and ideas.

The team-up shot

A major trope of the superhero movie genre is the team-up shot. This typically occurs just before the final battle, when the heroes have finally assembled and are ready to kick some serious butt. Often, the allied characters stroll confidently toward the camera in a straight line. Sometimes they even saunter in slow-motion, their stylized strutting set to a recognizable needle drop for effect. "The Guardians of the Galaxy" movies boast some of the best examples. But "The Flash" is saddled with one of the worst.

At the start of the fight against Zod's army, the two Flashes land after being dropped from the Batwing just as Supergirl makes contact with the dirt beneath her feet. All three had been (theoretically) moving so fast, they have to brace themselves before skidding to a stop in what was supposed to be a still-photo-worthy final formation. Everything about this team power walk falls short. The characters look like clip art against a screensaver. The lightning and smoke sizzling from their bodies look like the first draft of an effect that was supposed to be improved upon in post-production. The dual Ezra Millers and Sasha Calle move inorganically, although probably through no fault of their actors. And even if the VFX had served its purpose, the shot composition isn't that compelling. What should've been a marquee image is instead one of the most obvious CGI failures of the final product.

The Batcave

Just as Michael Keaton's Batman returns as a supporting player in "The Flash," the 1989 Tim Burton film's Wayne Manor becomes one of its most important settings, as does the Batcave. "Batman" may have been limited by the available technology of the time, but Burton and his production designers embraced those limitations and created a superhero movie that was as campy as it was gothic. Burton's "Batman" was so successful in this regard, it won the Oscar for what was then called best art direction and set decoration. Flash forward 34 years, and technological advancements have only cheapened the once-mythical Batcave.

This time, Bruce Wayne's secret lair is glaringly comprised of a physical set not-so-seamlessly blended together with a digital background. As prime Flash clicks away on Bruce's keyboards and alternate Flash explores the place, the waterfall that gives the Batcave its cover can be seen on the other side of a railing. While the rest of the Batcave is admirably real and looks that way on screen, the world on the other side of that railing gives off screensaver vibes. Throughout every subsequent scene that takes place at this location, water continues to fall generically, uniformly, and at a distance that makes it obvious that this waterfall isn't actually there. Though innovations such as LED volume screens should make these kinds of atmospheres more realistic, the quantity and the quality of the digital images make it harder than ever to suspend disbelief.

The final fight

We should cut DC and Warner Bros. a little slack here. "The Flash" has an especially messy-looking third act, but it's in good company. The film is simply the latest superhero installment that suffers from ever-deteriorating visual effects as it hurtles toward its climax. Comic book adaptations have been taking heat for bad CGI final battles for years, but we can only cut Muschietti and company so much slack. "The Flash" is an average movie with an awful final battle, not a great movie with some janky rhinos. From its underbaked stakes and uninteresting production design to its bland fight choreography and amateurish use of CGI, the militaristic confrontation between General Zod and Supergirl, with Batman and the Flashes on sidekick duty, just doesn't work.

There's a lot to pick apart — every crash, boom, bang, and character that emerges from a melee looks pretty fake — but let's focus on the ugliest of the ugly. When Kara and Zod engage each other in combat, their superhumanoid digital selves are so non-specifically realized, the viewer feels no force behind any of the punches and no gravity behind any of their acrobatics. Any pause in the action would reveal just how lazily done it all was. Just as visually unexciting is the hoard that makes up Zod's army, barely visible over the shoulder of the two Barrys who frame most of the battle in an uncomfortable close-up.

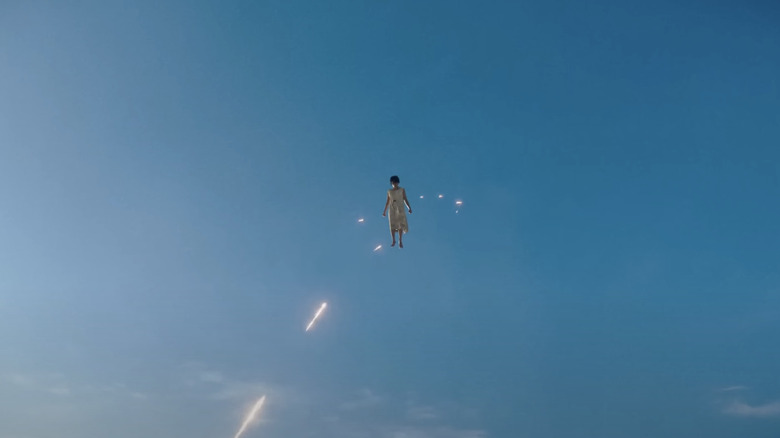

Kara's Russian flights

Sasha Calle has been getting good press for her portrayal of Kara Zor-El aka Supergirl, the Kryptonian who Batman and the Flashes journey to Russia to free in an effort to stop Zod from terraforming the planet. But surely those flattering reviews have more to do with her acting in between big set pieces. It's not Calle's fault that Kara and her fighting style account for some of the most embarrassing VFX in the movie: Filmmakers just didn't know how to digitally enhance Supergirl's skillset. This becomes painfully apparent the first time we see her in action. When she springs to life on the roof of her heavily guarded Siberian prison, we realize that this Kara isn't bound by even the laws of physics that would apply to Superman. Her figure darts about, knocking out Russian operatives, like a limp doll being played with by an overly enthusiastic child.

Anyone who complained about General Leia's Mary Poppins-esque flight through space in "The Last Jedi" should have a much bigger problem with Kara Zor-El's aimless zig-zagging across the sky in "The Flash." The second-rate use of CGI to animate Supergirl's movements is rivaled only by its efforts to make it appear as though bullets are bouncing off of her. Little gold flares, almost like a Snapchat filter, pepper her outfit. As strong as Calle's performance is, the weakness of her character's digital rendering make it seem like she isn't ever in any real danger.

The Speed Force time travel coliseum

The plot engine that drives "The Flash" is the point in the time-space continuum where Barry ends up when he runs fast enough to travel into the past. This is depicted as a series of circles folding in on themselves, with visual representations of his memories in each circle. Together, they make up what looks like a coliseum, and Barry is there like a gladiator fighting for his life. The Speed Force time coliseum isn't a very intuitive way to visually communicate the paradoxes that Barry creates when he goes back to the fateful day of his mother's death. But even if it was, the atrocious CGI that's used to bring the past to life would've drastically undercut it.

If you thought "Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania" was the equivalent of digital paint thrown meaninglessly on the screen in a misguided attempt at being artistic, wait until you see Henry Cavill's Superman and Jason Momoa's Aquaman (plus some babies in mortal peril) as if illustrated by barely functioning AI, as part of a collage of only semi-related DC Comics nonsense. Every time Barry goes back to this cursed place, it looks stupider and stupider. The rows of faces from Flash's past and future are, from a design perspective, no different than if Muschietti had purchased a few dozen life-sized cardboard standees from a novelty store, arranged them around the perimeter of a room, and lit them with a color-changing strobe light. Visually, the Speed Force time travel mechanism is too ridiculous and incompetently done to be taken seriously.

The Supermen cameos

This next use of CGI is ethically and aesthetically problematic. "The Flash" is overstuffed with cameos, some calling back to the DCEU's past, while others reference much earlier Warner Bros. and DC collaborations. Digital effects were used to make some of these cameos possible, and whether audiences think the reality tampering was worth it is up for debate.

During the worlds collide sequence near the end of the film, clips of George Reeves, Christopher Reeve, and Nicolas Cage are played in a montage (Helen Slater's Supergirl also appears). George Reeves played Superman in the "Adventures of Superman" TV series which ran from 1952-1958. Christopher Reeve, probably the actor most associated with the role, famously played the character in three feature films from 1978 to 1983. Nicolas Cage very nearly starred in a project called "Superman Lives," which would've been directed by Tim Burton. The Cage cameo is, depending on your perspective, a harmless Easter egg or an eye-roll-worthy bit of pandering that distracts from what's supposed to be an emotionally charged segment of the movie. Either way, it looks rough... like something an enterprising young fan would make on a phone and post to TikTok.

Potentially more divisive (and just as rough-looking) are the posthumous appearances by Reeves and Reeve. Though Muschietti may have intended the cameos to honor their legacy, some fans have argued that plopping deceased actors into a movie without their permission is disrespectful.

The baby in the microwave

"The Flash" could've been marginally better with even middle-of-the-road visual effects. But it's also possible that the movie's reputation never could've recovered from an almost too-absurd-to-be-believed early action scene that combines some of the most bizarre storytelling choices with some of the most bizarre computerized human creations in movie history. As Affleck's Batman pursues a carful of criminals, Flash is left to evacuate a collapsing hospital — and on an empty stomach no less. Eight babies, a neonatal nurse, and a service dog all begin to plummet to their deaths. To add an extra layer of absurdity, one of the babies is falling toward an array of knives, one is about to be splashed with acid, and one is about to be crushed by a heavy object.

After vandalizing a vending machine and heating up a burrito midair, Barry calculates the steps he'll need to take in order to save everybody's lives. This includes placing one of the babies in a microwave. Filmmakers definitely weren't going to drop a real baby from hundreds of feet in the air in a cooking appliance, but the CGI that's used to make it seem as though Flash has indeed put a baby in a microwave is every bit as disturbing as the act itself. The newborn's face is as unsettlingly inhuman as the kids from "The Polar Express" or the first "Toy Story." Sensitive audiences might be re-traumatized when microwave baby shows up as one of the hallucinatory images in the Speed Force's time travel coliseum.