Why Aladdin 2 Only Got A Direct-To-Video Release & How It Changed Disney

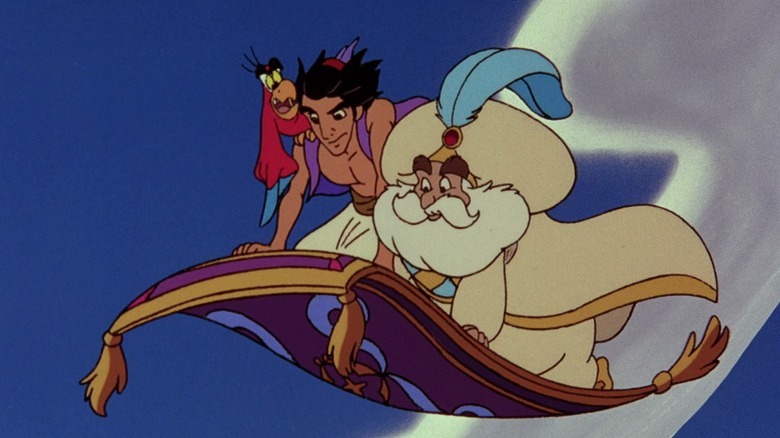

The cultural preponderance of the Disney Renaissance and its various era-defining animated films goes pretty much without saying nowadays. For evidence of how much these late-20th-century hits are ingrained in our collective cultural imagination, you needn't look any further than the ongoing wave of Disney's live-action remakes. Out of the 16 live-action and photorealistic reimaginings released by Walt Disney Pictures since 2014's "Maleficent," five have been based on Renaissance titles, including the three highest-grossing ones so far — Jon Favreau's "The Lion King," Bill Condon's "Beauty and the Beast," and Guy Ritchie's "Aladdin."

The 2019 "Aladdin" remake, in particular, is demonstrative of the staying power that these films have had over the past three decades; even though the original "Aladdin" wasn't a history-making box office phenomenon on the level of "The Lion King" or a Best Picture-nominated critical landmark like "Beauty and the Beast," its story still held a big enough place in audiences' hearts to carry it to a $1 billion-plus worldwide haul. Of course, it does bear noting that "Aladdin" was aided in its cultural consolidation by being the first Disney Renaissance film to get a sequel, and then the first one to get a threequel. For a variety of reasons, the sequel in question, 1994's "The Return of Jafar," was released directly to home video instead of playing in theaters like its predecessor — but it was still a watershed moment in Disney history that left the studio, its production pipeline, and its overall cultural standing forever changed.

Disney was historically resistant to making sequels

Not only was "Aladdin 2: The Return of Jafar" the first-ever sequel to a Disney Renaissance film, but it was also the second Disney animated feature sequel ever, following 1990's "The Rescuers Down Under." For a studio that had been making films since the silent era of Hollywood, Disney sure seemed to charge suddenly and rapidly into the business of franchise extensions. And the explanation for that dramatic change having come so late boils down to the fact that Walt Disney himself was notoriously resistant to the idea of making sequels to past hits.

Save for the Mickey Mouse crew and their recurring adventures, Walt personally didn't see much use in bringing successful characters back just for the sake of it; he personally preferred for hit films to be used as creative blueprints for brand-new stories. This philosophy extended even to the short films that Walt Disney Productions used to specialize in, as evidenced by the laborious behind-the-scenes strife it took to convince Walt to give the go-ahead on a sequel to 1933's "Three Little Pigs" (via Collider). As he used to put it, "You can't top pigs with pigs!"

This no-sequel mindset became foundational enough at Disney that, even after Walt's passing in 1966, the Mouse House continued to make strictly one-and-done animated features for the next two decades. It was only after Disney went through a massive crisis and a change in management in the 1980s that animated sequels started getting made.

Aladdin 2 came in the context of a business overhaul

Between the scattered leadership following Walt Disney's death, a general decline in American audiences' interest in animation, and a series of economic downturns, Walt Disney Productions faced its biggest crisis in history going into the 1980s. In 1984, that crisis prompted one of the most notable changes in management in American film history, in which Michael Eisner and Frank Wells were respectively appointed as Disney's new CEO and president.

Eisner and Wells' strategy for rescuing Disney from its ongoing slump involved re-shaping it from a dominant animation house that was also taking tentative steps into family-friendly live-action film production to a major movie studio and all-out media empire. Saving Disney Animation, the company's historical yet long-neglected crown jewel, was a particularly crucial task in that new plan, and it was overseen by Peter Schneider, who presided over Disney's animation department between 1985 and 1999. Under Schneider's more financially pragmatic management, the historical no-sequel custom was overturned for the first time, with a sequel to the studio's most successful recent film, 1977's "The Rescuers," being greenlit as a sure-thing way of testing the new Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) (via Collider).

Although "The Rescuers Down Under," released in 1990, didn't quite live up to economic expectations, it still served to break the animated feature sequel taboo at Disney, and the company would usher in a new, much more brand-extension-friendly era on its heels — which would eventually include "The Return of Jafar."

The Return of Jafar was originally intended as a TV series

Among the many tenets of the concentrated push for growth of the Eisner/Wells era, one was to explore other platforms beyond theatrical film more incisively, which led to the creation of a Disney Television Animation division in 1984. Where Disney had previously only dabbled in TV animation with interstitial short segments, the period from 1985 onward saw the company produce original animated series for the first time. Shows like "Adventures of the Gummi Bears," "DuckTales," and "Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers" quickly proved that the format was a potential economic goldmine.

It was in the TV division that Disney first tried out an extension of one of its Renaissance hits, with the "The Little Mermaid" prequel series that aired on CBS between 1992 and 1994. The project that would eventually become "Aladdin 2: The Return of Jafar" started out as another such TV-bound extension, with "Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers" creators Tad Stones and Alan Zaslove being enlisted to develop an "Aladdin" animated series. While planning out the series, Stones and Zaslove found themselves twisting into narrative knots to bridge the gap between the open-and-shut happy ending of "Aladdin'" and a new set of adventures. What new perils could befall Aladdin after marrying Jasmine and becoming the well-off prince of Agrabah? Why would the Genie come back after leaving? Eventually, the explanation they came up with became so complex as to call for feature length.

The film's success opened a new home video market for Disney

Even after the story of "The Return of Jafar" had ballooned beyond the length of a half-hour TV pilot, it was still intended to run on TV as a one-hour premiere event of sorts for the "Aladdin" series. Although Tad Stones saw potential in it for a direct-to-video film, Peter Schneider and Michael Eisner were initially resistant to the idea of releasing an all-out home video sequel, as they felt it might cheapen Disney's brand reputation. Eventually, though, Disney executives were so impressed by the quality of the animation and design work being done at a rapid pace on "Jafar" that they decided the film was worthy of its own standalone release. Due to the much faster pipeline enabled by the non-theatrical release and the enormous success of "Aladdin" on VHS, the sequel was kept as an incursion into the home media market.

As it turned out, that market was brimming with untapped potential: Budgeted at $3.5 million, "The Return of Jafar" is estimated to have made over $300 million in sales worldwide. From there on out, a door was opened at Disney. The company began to produce a nonstop barrage of direct-to-video sequels to beloved animated titles, with the division responsible for them eventually consolidating under the name DisneyToon Studios in 2003. And nothing was ever the same again for the House of Mouse.

Disney direct-to-video sequels became an institution unto itself

"The Return of Jafar" didn't curtail the original plans for the "Aladdin" animated series, which aired three seasons between 1994 and 1995. As a cap to the series' continuity and to the franchise in general, Disney then made what became its second direct-to-video sequel, titled "Aladdin and the King of Thieves," which was released in 1996.

Following the unexpected success of the "Aladdin" sequels, two follow-ups to "Beauty and the Beast" were released in 1997 and 1998, followed by sequels to "Pocahontas," "The Lion King," and "The Little Mermaid." By 2001, Disney was confident enough in that new business to look even further back in its catalog for inspiration; the early 2000s saw continuations of "Cinderella," "101 Dalmatians," "The Jungle Book," and "Peter Pan" — with the latter, 2002's "Return to Never Land," becoming the rare production from Disney's DTV wing to score a theatrical release.

The rest is, of course, history — any kid who grew up in the 2000s is likely to have vivid memories of the direct-to-video Disney sequels. It was not until John Lasseter became Disney Animation's new CCO following the buyout of Pixar in 2006 that the DTV sequel pipeline was closed down, as Lasseter felt that it was cheapening the legacy of the original films. DisneyToon Studios then pivoted to making "Tinker Bell" and "Planes" films, before finally closing down in 2018, nearly 30 years after "The Return of Jafar" began production. Talk about a street boy who made an impact.