The Ending Of Asteroid City Explained

"Asteroid City" crash lands into theaters at a time when its writer and director, Wes Anderson, has suddenly become a pop cultural reference point, particularly for millennial and Gen Z users of TikTok. The 54-year-old auteur began trending because his aesthetic is so singular and recognizable, artificial intelligence — the existential panic topic of the moment — can attempt to duplicate it for the purposes of making amusing two-minute faux-trailers. "Asteroid City" (which is largely about existential panic) proves that, no matter how sophisticated AI gets, nobody and nothing will ever be able to Wes Anderson like Wes Anderson. His 11th feature film is his most self-referential to date, meticulously pieced together from every previous trick he's ever pulled out of his bag. There's a framing device, a gaggle of forlorn male protagonists, a teenage couple innocently falling in love, a conspiracy plot, wryly absurdist humor, stone-faced acting, and of course, hyper-stylized costumes, sets, props, and camera compositions.

It's also his most challenging film to date. That framing device and those references are so multilayered and, at times, confusing that viewers almost have to choose whether they want to figure "Asteroid City" out or just enjoy the trip. Those who go with the second option may want to revisit the complicated plot mechanics and dense themes after the fact, while those who go with the first option may have missed a key point along the way. In either case, "Asteroid City" shows that Wes Anderson and his work are much more substantial than memes about symmetry and whimsy suggest. Let's explain the ending of "Asteroid City."

What exactly am I watching?

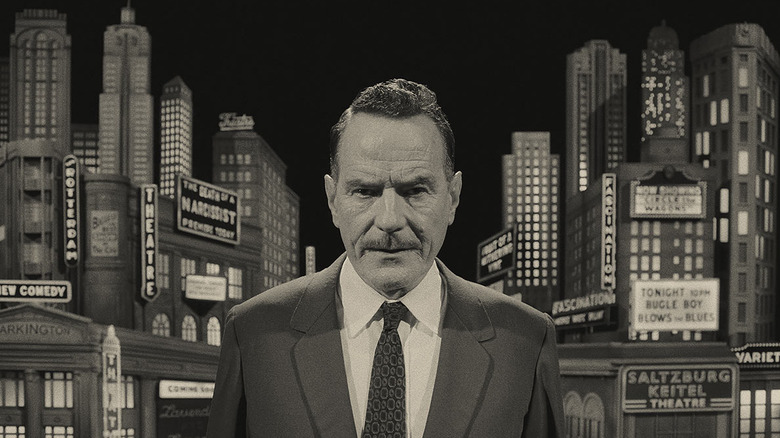

"Asteroid City" unfolds via a story-within-a-story structure, which, in and of itself, can create confusion. Anderson helps the audience out somewhat by introducing the film with a prologue and by distinguishing the narratives through the use of color and aspect ratio. But even then, he purposefully breaks his own rules on occasion to create more distance and artifice. Not to mention, that prologue informs viewers that nothing they are about to see is real. "Asteroid City does not exist," Bryan Cranston's TV host narrator says as the film opens. "It is an imaginary drama created expressly for the purposes of this broadcast. The characters are fictional, the text hypothetical, the events an apocryphal fabrication."

What moviegoers are watching is a fake TV special from 1995. That TV show is about the production of a fake play called "Asteroid City." So far, everything that falls under those umbrellas is presented in black-and-white and in 4:3 aspect ratio. The content of the fake play itself, which takes place in September of 1955, is shot in full-color widescreen. However, in one comedic moment, Cranston's host breaks the fourth wall of the technicolor narrative before realizing he's made a mistake.

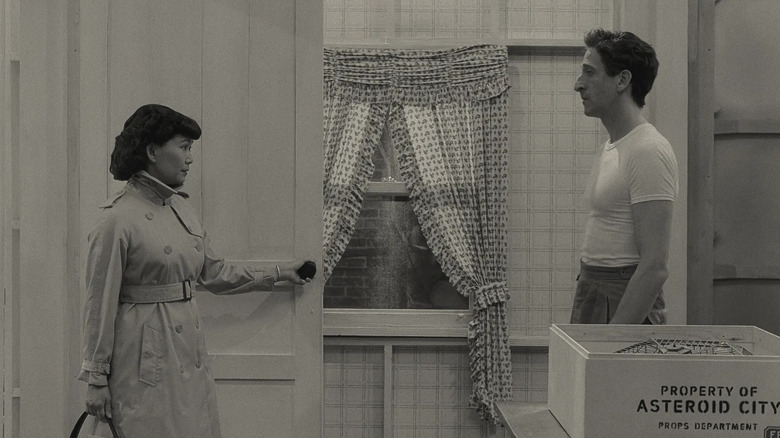

Who the real actors are playing is just as convoluted. Jason Schwartzman portrays both Jones Hall, a fake actor, and Augie Steenback, the protagonist of the fake play, while Scarlett Johansson is Mercedes Ford, the mistreated actress who returns to the role of Midge Campbell ... herself, a mistreated actress. With the exception of Edward Norton, Willem Dafoe, Adrien Brody, and Hong Chau (all of whom only appear in the black-and-white behind-the-scenes production), everyone is an actor as well as a character.

What's going on in the story?

In the black-and-white half of "Asteroid City" (it's actually quite a bit less than half of the runtime), a once-renowned but currently troubled and reclusive playwright named Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) is battling writer's block as he toils away at his latest project. Local actor Jones Hall shows up at his home to perform a monologue from the script in the hopes of landing the lead role. He stays, helps Earp refine the story and the character of Augie Steenback, and starts an implied affair with the eccentric scribe.

Meanwhile, hot-headed director Schubert Green (Adrien Brody) is living in the wings of the theater during the run of the play. His life is falling apart. His wife (Hong Chau) and seeming collaborator or muse is leaving him. His demeanor nearly causes his lead actress (Johansson as Ford) to quit. The understudy for the role of Woodrow Steenbeck (Jake Ryan) convinces her to return, and rehearsals for "Asteroid City" get back on track. As a result, the understudy is promoted.

Earp, Green, and the theater company with whom they collaborate, led by acting teacher Saltzburg Keitel (Willem Dafoe), are all searching for a deeper meaning in the play's resolution ... meaning that doesn't come easy. The supposed true story-style TV re-enactment is focused on following these "real-life" characters and exploring how their struggles conversely inform the text and subtext of the play, "Asteroid City."

What's going on in the story within the story?

In the fictional work of fiction that is "Asteroid City," a war photographer named Augie Steenbeck takes his teenage son, Woodrow, and his three young daughters to the Junior Stargazers astronomy convention held in the tiny western town that's sprung up around the site of a meteor's impact. Woodrow's invention (which casts an image of the American flag onto the moon) has been nominated for a scholarship. He's competing against four other Junior Stargazers, including Dinah (Grace Edwards), whose mother is actress Midge Campbell. Augie is possibly suffering from PTSD and the effects of shrapnel to the head, but worse, he must confess to his children that their mother died three weeks ago after a prolonged illness. His disapproving father-in-law, Stanley (Tom Hanks), arrives to hold him accountable.

Also in attendance are members of the U.S. military (Jeffrey Wright and Tony Revolori), an astrophysicist named Dr. Hickenlooper (Tilda Swinton), a teacher named June (Maya Hawke) and her grade school-aged students, and a small band of cowboys led by Montana (Rupert Friend). During the proceedings, Woodrow and Dinah form a bond, as do Augie and Midge and June and Montana. The announcement of the scholarship and the three budding romances are interrupted by an alien who descends from a flying saucer only to make off with the meteorite that is Asteroid City's only tourist attraction. Augie snaps a photo of it. The American government imposes a quarantine, and the participants are debriefed and subjected to psychological testing. They continue to form bonds as they try to figure out what happened and what it might mean for the future.

What happens to the cast and crew of Asteroid City?

The backstage production is definitely the B plot in "Asteroid City." Its narrative isn't as linear and isn't as cleanly resolved as the plot of the play. In some ways, the black-and-white portion is the emotional inverse of the colorful parts. Things start out with hope and romance and end with open questions and tragedy.

In one of the quirkiest ever Wes Anderson scenes (and that's saying something), the entire company of actors is instructed by Conrad Earp, Schubert Green, and Saltzburg Keitel to participate in an improv exercise. Earp wants to include a metaphorical scene in which everyone falls asleep. One actor spontaneously screams, "You can't wake up if you don't fall asleep," and the rest follow, chanting the line until it becomes a full-throated mantra.

Earp does complete his play (though his director and actors struggle to understand it), which enjoys a six-month run before he's tragically killed in a car accident. As far as we know, Director Green doesn't get his life together, but he does start to get through to his lead actor, Hall, who fears he hasn't gotten Augie "right." On the night in question, Hall wanders out to a balcony to have a smoke and happens upon the actress who had been cast in the role of Augie's wife (Margot Robbie) before her role was cut. She recites what was their dialogue with him in a scene that mirrors previous exchanges between Augie and Midge. The actor who plays the mechanic in "Asteroid City" (Matt Dillon) comes to fetch Hall, who's missed his cue, and he lingers awhile on the balcony to flirt with the actress before the TV program draws to a close.

What happens to the characters in Asteroid City?

Easier to follow (and to invest in) is what becomes of Augie, Woodrow, Midge, Dinah, and the rest of the visitors to Asteroid City. The Junior Stargazers scheme to get the truth out there by rigging an off-limits payphone and connecting to the editor of their school newspaper. When the alien becomes a national sensation, Asteroid City becomes a much more significant and kitschy tourist trap overnight. Dinah catches Augie and Midge about to go to bed together. The parents of the quarantined students are shipped in but held in a containment facility. June shares a dance with Montana. And just when the winner of the scholarship is about to be announced and the quarantine is about to be lifted, the alien returns to replace the meteorite it had taken and subsequently cataloged.

After another government-mandated quarantine, Augie wakes up to find that he and his family are the last people in Asteroid City. Everyone else has returned home. Stanley attempts to exhume his daughter's ashes, but the three girls insist upon keeping her Tupperware-bound remains in the ground where they put her, covered in a thin layer of dirt and wildflowers. Augie, Stanley, and the kids patronize the only local restaurant one last time, ordering the usual black coffee and flapjacks. The server gives Augie a slip of paper that contains Midge's P.O. Box. Stanley tells his son-in-law that he approves if Augie wants to pursue a relationship with the "gifted comedienne," and Woodrow reveals that he was the winner of the $5000 scholarship (which he plans to spend on his new girlfriend, Dinah).

Why does Augie burn his hand?

One other piece of business that happens near the end of the play is that, without warning, Augie purposefully burns his hand on a portable griddle while he's making a grilled cheese sandwich. This moment comes just after he and Midge are discussing whether they're at the beginning or the end of something, their dalliance having been found out by their kids. Augie's self-harm is foreshadowed several times throughout the film. Jones Hall, in his first meeting with Conrad Earp in his home, presses the playwright to explain Augie's motivation and later workshops the reason others are involved in the production. Various possible answers are given. He's processing the loss of his wife. It's just what's in the script. But the question looms over the entire movie like the first half of a thesis statement.

Obviously, the very specific wound that Augie inflicts upon himself is figurative, standing in for a larger idea that interests Anderson. That is, why do we do anything that we do? The nesting doll format provides one perspective: perhaps some actions are partially predetermined by previous actions. Augie burned his hand because the grill was there when he felt compelled to do something so extreme. Whether it was put there by life, a playwright, a director, or Augie himself is, in a way, beside the point. Similarly, there are myriad explanations as to why he may have felt compelled to do something so extreme. Augie's motivation could've been persistent grief or a passing impulse. People behave unpredictably for both reasons, and not everyone's actions are sensibly related to or in proportion to their thoughts and emotions.

What does the TV documentary mean?

"Asteroid City" boasts Wes Anderson's most stacked cast yet. Frequent collaborators Jason Schwartzman, Edward Norton, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Tilda Swinton, Jeffrey Wright, Jeff Goldblum, and Tony Revolori are all back, joined by first-time Anderson cast members Tom Hanks, Steve Carrell, Scarlett Johansson, Matt Dillon, Hong Chau, and Hope Davis. The writer-director and all those actors have a lot to say about the entertainment industry, the creative process, and their craft.

Schwartzman's actor character, Jones Hall, seems to be loosely based on Marlon Brando and James Dean, famed pupils of the Stanislavski System, sometimes referred to as method acting. Dafoe's Saltzburg Keitel is a Lee Strasberg-type. Strasberg was an influential acting teacher who expanded upon Stanislavski's method under whom Brando, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe studied. Both of Johansson's characters are modeled after Monroe, who, like Midge, had multiple husbands, endured cruel treatment by some of the men in her life, and whose talents (especially for comedy) went under-appreciated in her lifetime. Midge's grease paint black eyes harken back to this sad fact.

Norton's Conrad Earp isn't a Wes Anderson one-for-one, nor is Brody's Schubert Green, but the auteur is still speaking through both characters about his own experiences as a storyteller. Earp is a Tennessee Williams dupe, while Green is more like if Stanley Kowalski played Elia Kazan. "Asteroid City" simultaneously celebrates the rich history of and pokes fun at the pretentiousness of 20th-century American theater and film. In an even more meta way, it does the same to Anderson's own body of work.

What does the play mean?

More universal themes can be pulled from Earp's play. On a surface level, Anderson is referencing Shakespeare's "Macbeth" with Augie's three witchy daughters and Roswell with his space and alien-obsessed western town. A layer deeper, "Asteroid City" is critical of American patriotism, militarism, and capitalism. Woodrow's invention plants the stars and stripes on the moon 14 years before Neil Armstrong. The United States Military-Science division and a shady nonprofit sponsor the Junior Stargazers convention. The teens get medals and sashes, but the Pentagon gets to steal their research. When the general public is captivated rather than terrified by news of the alien, a whole cynical economy develops around the site where the modest meteorite once sat.

But at its deepest level, "Asteroid City" is about alienation and the existential dread of having to face the unknown. The attendees debate whether aliens exist. Anderson is substituting the question of whether we're alone in the universe for the question of whether we're alone in our lives. Augie, Woodrow, Midge, Dinah, June, Montana, Stanley, and even the motel manager are all dealing with loss, loneliness, or both. Augie considers temporarily abandoning his children, and Midge thinks she and Augie understand each other because they're both broken but reluctant to express their pain. Importantly, the characters and the audience never get definitive answers as to why the alien came or why Augie burned his hand. He reads doom into the alien's deer-in-headlights expression, and little mushroom clouds can be seen in the distance. Yet, even though everything isn't okay during and at the end of "Asteroid City" (there are clear parallels to COVID), everyone learns to cope and their lives go on.

What has Wes Anderson said about Asteroid City?

Wes Anderson movies have their author and director's potent signature on them (Anderson himself calls it "recognizable handwriting"), but they're also a pastiche of his many fascinations. Viewers might guess that a love of sci-fi was the starting point for "Asteroid City," and Anderson admits his own daughter prefers "Star Wars" to his films. But in reality, it was the New York theatre scene and Los Angeles film scene of which people like Brando and Kazan were a part that served as a launch point. He recently told Indiewire that the directors, actors, and films of the 1950s have been an age-old inspiration since he and longtime friend Owen Wilson discovered them in their teen years. He's also "susceptible to the mystique of a backstage story," which provides "Asteroid City" with half of its plot.

Anderson loves his actors and actors love working with him. His own ever-growing troupe now includes Tom Hanks, whom he calls "a full-on icon." He and Hanks share an interest in the American midcentury as well as a work ethic. Another seasoned performer, Steve Carell, stepped in to fill the role that had been written with Bill Murray in mind when Murray contracted COVID during production.

As for those AI-generated memes, Anderson has heard about them, but he hasn't seen them. It's not a matter of principle. "I've never seen a TikTok," he admitted to The Daily Beast's Obsessed.