Animated Films That Completely Changed At The Last Minute

All movies go through changes between the point that they're first conceived and the day they come out. By nature, animated movies are especially likely to go through big changes, whether it's tweaking the artwork/effects or re-doing voice recordings to match what's happening on the screen. But just because it's technically more doable than in live-action filmmaking, that doesn't mean making such changes is easy with animated movies, especially when it comes down to the wire — the more work that has already been finished, the harder it is to dramatically reimagine.

The following animated films were still making significant changes anywhere from two years to two weeks before release. Considering these movies often take four or more years to make (one entry took a whopping 29 years!), that's awfully late in the day for the scale of the changes being made. Whether such changes are worth it varies, both in terms of the quality of the finished product and in the ethics of putting the animators through these revisions on such a tight schedule. Read on to find out which animated films were completely changed at the last minute.

The Black Cauldron

1985's "The Black Cauldron" had an unusually long development cycle. Disney bought the rights to Lloyd Alexander's "The Chronicles of Prydain" books in 1971 and hyped it up throughout the next decade as having the potential to be the next "Snow White" in terms of artistic ambition. The project burned through different directors and artists — perhaps the biggest missed opportunity was not using any of Tim Burton's concept art. After much tinkering, the movie was finally nearing its planned release in 1984, but there were some sudden changes at the top and new studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg requested even more major alterations.

"The Black Cauldron" was the first Disney animated movie to earn a PG rating from the Motion Picture Association of America due to its violence and horror — and the original cut of the film was even scarier. Katzenberg hated it so much that he even edited some of it himself! 12 minutes of footage — including much of the climactic sequence with the Cauldron-Born zombies and some gruesome scenes in which henchmen are melted down to skeletons — were reportedly axed and the release date was pushed to the following summer to allow for continuity adjustments. The film ended up being such a massive flop that it put the future of Disney's animation studio in question for a time.

Beauty and the Beast

The 1991 version of "Beauty and the Beast" that became an instant classic and the first animated best picture nominee at the Oscars had an unusually short production time of only two years, as opposed to the typical four or more for a Disney animated feature. That's because Disney had already spent two years producing a completely different version, only for studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg to scrap it and restart production from the ground up with a different crew in a different country. "Beauty and the Beast" was originally to be helmed by the British husband-and-wife directing team Richard and Jill Purdum. Their version of the fairy tale had a very different art style, was not a musical, and included an evil aunt for Belle similar to the stepmother in "Cinderella."

The Purdums left the project shortly after Katzenberg's demand for a rewrite, with Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale replacing them as directors. Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, the duo behind the music of "The Little Mermaid," were brought on as songwriters. The production left London and moved back and forth between Los Angeles and New York to accommodate Ashman's failing health — he died from heart failure caused by the AIDS virus before the film hit cinemas, though a press screening took place four days before his passing and he was informed that his final project was set to become a big success.

Aladdin

Alan Menken and Howard Ashman were initially reluctant to take the "Beauty and the Beast" job because their real passion project was 1992's "Aladdin." Ashman wrote the original treatment for the film, originally pitching it as a campy throwback to '30s musicals. Co-directors John Clements and Ron Musker (who co-penned and co-helmed "The Little Mermaid" for the Mouse House) were given the task of padding out the story, though the direction they took didn't sit right with Jeffrey Katzenberg. When they showed the studio chairman what they had in April 1991, he asked them to start over.

"Aladdin was the least interesting person in the movie," Katzenberg told the Los Angeles Times. "Whenever he was in a scene with Jasmine she so overwhelmed him with her personality and intelligence, it was like he wasn't even in the scene. He was transparent. You didn't care about him. Now, how do you have a movie called 'Aladdin' where Aladdin isn't worth caring about?" Changes were made to the script and the titular character was redesigned to look less like Michael J. Fox, as animator Glen Keane had envisioned, and more like Tom Cruise, who had impressed Katzenberg in "Top Gun."

Katzenberg was finally satisfied with the script by October 1991, but he still tinkered with the film deep into production, requesting that some jokes be removed the month before the film was due to hit cineplexes. "Jeffrey believes that until the paint is dry, changes can always be made," Musker said.

The Thief and the Cobbler

"The Thief and the Cobbler" is seen as the film that inspired "Aladdin" — in fact, the Disney classic "sometimes comes perilously close to ripping off 'The Thief and the Cobbler,'" says The Verge. "Both movies feature an evil vizier with a pet bird, and a rotund king with a beautiful daughter. And Aladdin and his pet monkey share characteristics with both [Robin] Williams' thief and cobbler. There's an uncanny similarity in visual design between the two films — and the two viziers in particular." The main difference is that you've probably never heard of "The Thief and the Cobbler."

Development began in 1964, but the film wasn't released until 1993. For the first eight years of production, it was an adaptation of Idries Shah's books about Mulla Nasrudin, a folkloric figure from the 13th century. Director Richard Williams (who created the illustrations for the books) and his team animated three hours of footage for this version of the movie, but it played more like a series of shorts than a cohesive feature. Williams lost the rights to the Nasrudin material after a falling out with the Shah family in the 1970s, but he kept the rights to his thief character and worked his scenes into an original story.

In the 1980s, Warner Bros. acquired "The Thief and the Cobbler," but execs later got cold feet when they realized that it differed greatly from Disney's smash-hit musicals and eventually backed out. The 1993 Australian release "The Princess and the Cobbler" added musical numbers with worse animation and dubbed dialogue over the previously mute protagonists. Miramax butchered it even further as 1995's "Arabian Knight."

Toy Story

Like "Beauty and the Beast" and "Aladdin," John Lasseter's seminal computer animated comedy "Toy Story" had to be completely reworked. However, where Jeffrey Katzenberg's notes ended up improving those two Disney Renaissance films, this time it was Katzenberg who was responsible for the mess Pixar's first feature had gotten into. Fearful a movie about toys would be seen as kids' stuff, Katzenberg pushed for more sarcastic and adult humor, but this quickly turned Woody into an unlikable character. According to Walter Isaacson's Steve Jobs biography (via /Film), when Katzenberg asked fellow executive Thomas Schumacher why Pixar's reels were so bad, Schumacher answered, "Because it's not their movie anymore. It's completely not the movie John set out to make."

The plug was pulled on the production, despite the fact that they "had done almost an entire version of the full film, which they had then gone off and done a lot of the animatics and storyboards to," lead voice actor Tom Hanks told Yahoo! Movies UK. Lasseter went to Katzenberg to ask for another chance. Remarkably, he was given just two weeks to fix the issues, but his team pulled it off. Katzenberg approved this new version, which re-entered production in February 1994. Further tweaks were made to the ending following a mixed test screening in July 1995, only five months before the groundbreaking film's wildly successful theatrical release.

South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut

The makers of "South Park" are used to working on a tight schedule. The adult cartoon's simplistic animation style makes it possible to crank out an episode in less than a week, allowing an unusual level of timeliness for its topical satire. Of course, theatrical features can't be made so last-minute, but the final cut of 1999's "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut" came awfully close due to a protracted battle with the MPAA.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone were already pushing things by aiming for an R rating rather than the studio-preferred PG-13. However, even Parker and Stone realized that an NC-17 rating — the one above R in the ranking — was too much. It meant that nobody under the age of 17 would be permitted to see the film, which would have severely hurt its chances of succeeding. "We submitted it seven times to the MPAA," Stone revealed at the time. "The last submission we got back was NC-17, two weeks before release." After a series of angry phone calls between producer Scott Rudin, Paramount execs, and the MPAA, the rating was downgraded to R.

What's funny is that some of the jokes actually got dirtier in the editing process. The film was originally supposed to be called "South Park: All Hell Breaks Loose," but execs didn't want the word "hell" in the name. Parker and Stone instead proposed "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut," a clear penis joke. Apparently, it went over the heads of the higher-ups at the studio.

Toy Story 2

The first "Toy Story" proved that Pixar could rework a bad movie into a great one in a limited amount of time, and the staff had to pull off similar miracles for 1999's "Toy Story 2." The sequel was originally conceived as a cheaper direct-to-video release directed by up-and-coming talent Ash Brannon and handled by the crew that animated the "Toy Story" CD-ROM games. Disney execs liked what they were seeing enough to bump it up to a theatrical release, but the Pixar brain trust was dissatisfied with how the film was turning out and wanted to start over.

The majority of the already-in-progress version of "Toy Story 2" was scrapped (only the Al's Toy Barn sequence remained generally intact) and a new version, with John Lasseter and Lee Unkrich joining Brannon as co-directors, was made in just nine months. "Effectively all animation was tossed," Pixar's former Chief Technical Officer Oren Jacob told The Next Web. "That was probably one of the biggest tests of what Pixar was as a company and a culture we ever went through." Though Pixar tried to limit overtime hours, the rushed production schedule led to long days and a third of the staff getting repetitive strain injuries.

The Emperor's New Groove

If you ever wondered how Disney ended up making a movie as wacky as 2000's "The Emperor's New Groove," it's basically because they needed to get any movie they could salvage from the ruins of a more traditional Disney musical titled "Kingdom of the Sun." Conceived of in 1994 by "The Lion King" director Roger Allers as an Incan twist on "The Prisoner of Zenda," "Kingdom of the Sun" had a slow development cycle, and by 1998 — with one third of the animation complete but still having story problems — it became clear the film wouldn't be able to make its planned summer 2000 release.

Mark Dindal, who had originally joined as a co-director, ended up pitching an alternate version of the film as a pure comedy, which pleased the studio heads. "The Emperor's New Groove" got made quickly with only a slight delay to a December 2000 release. Only two songs by Sting, who had been hired to write the music for "Kingdom of the Sun," made it into the film — the opening and closing numbers. However, his deal with Disney included allowing his wife Trudie Styler to film a documentary about the production. Given the unflatteringly candid look at the troubled process that the film presented, Styler and co-director John Paul Davidson's "The Sweatbox" has never been released by Disney outside of a brief awards-qualifying engagement in 2002.

Shrek

When it first went into development, 2001's "Shrek" was nearly unrecognizable from the movie people love and meme about today. Originally, "Saturday Night Live" star Chris Farley was going to lead the line as the ogre protagonist via motion capture in a live-action/animation hybrid. The production was troubled, with animators considering working on "Shrek" to be a punishment. "It was known as the Gulag," one animator revealed (via the New York Post). "If you failed on 'Prince of Egypt' [a DreamWorks movie that later flopped], you were sent to the dungeons to work on 'Shrek.'"

Things only got more difficult following Farley's tragic death in 1997. When Mike Myers was cast as Shrek, he requested a complete rewrite of the script for the now purely animated film. Then, after a rough cut was complete in February 2000, Myers insisted on yet another huge change: Re-recording all of his dialogue with a Scottish accent. It reportedly cost an additional $4-5 million to redo the lip sync animation, but this relatively last minute change ended up working extremely well.

Lilo & Stitch

If you've ever watched "Lilo & Stitch" and noticed that the characters suddenly appear a little off-model when they're getting into Jumba's spaceship for the big third act chase sequence, there's an explanation: The scene had to be animated at the last minute after the climax to the story was completely changed. Why the changes? Because, originally, the characters weren't flying in a spaceship through the mountains, but in a hijacked Boeing 747 between buildings in a busy city.

Animation on the Disney film was already nearly complete as of September 2001, but the terrorist attacks on September 11 suddenly made the original climax unusable for obvious reasons. Because the vehicles and most of the backgrounds in the sequence were CGI, it was possible to replace the computer models and get the reworked version together in time for the June 2002 release date. They needed to draw an additional scene of the characters getting into the ship, but most of the other hand-drawn character animation could be reused.

Hotel Transylvania

Sony's 2012 Adam Sandler vehicle "Hotel Transylvania" was in production for six years, and it went through six directors in that time. Originally, Anthony Stacchi and "Cow and Chicken" creator David Feiss were directing as a team. They were replaced by "Open Season" director Jill Culton, who was then replaced by Chris Jenkins and Todd Wilderman. In February 2011, Genndy Tartakovsky — the creator of "Dexter's Laboratory" and "Samurai Jack" — ended up taking the reins with just 18 months to make a complete film.

"They'd done the designs and backgrounds, so my challenge was to give it a tone and direction and have it make sense with all these existing different assets," Tartakovsky told Variety, adding that Sandler was initially skeptical when he was given the job. "Adam's used to working with his regular team, so I had to prove myself." Adding the father-daughter dynamic as the film's emotional core was one of Tartakovsky's ideas, which paid off big time.

Dracula's daughter Mavis also went through some big changes: She was going to be voiced by Miley Cyrus at first, but the character was recast with Selena Gomez in the role. Why? It was apparently due to a photo of Cyrus with a NSFW cake she bought for her then-boyfriend Liam Hemsworth. "I got kicked off 'Hotel Transylvania' for buying Liam a penis cake for his birthday and licking it," Cyrus claimed in a tweet.

Frozen

Based on Hans Christian Andersen's "The Snow Queen," the film that ultimately became "Frozen" was proposed by director Chris Buck in 2008. A former Disney man, Buck was working for Sony at the time, but John Lasseter wanted him to return to the Mouse House fold. "I pitched several ideas to John, and 'The Snow Queen' was one that he'd been interested in for a while," Buck said (via The Art of Frozen). "I pitched a musical version of it that he seemed excited by. So we started developing that project."

The film was put on hold in 2010, and when it went back into development in 2011, it was changed from a hand-drawn feature to a computer-animated one. Jennifer Lee came aboard in March 2012 to help with the screenplay, which was still struggling to make the characters work. Elsa was originally presented as more of a villain, and Olaf was apparently so obnoxious that Lee wanted to kill him. Lee got promoted to co-director in August 2012 due to her extensive involvement in the film's successful rewrites, which ultimately continued until June 2013 — just five months before the film's release!

Figuring out the songs was key to getting the film to work, with "Let It Go" solidifying Elsa as a sympathetic character. "Up until then, Elsa was pretty much a straightforward villain," Lee told the Pasadena Star News. "We wanted to know more about her, what she would be like if she could be herself without fear. After that, she was much more complex, more interesting and sympathetic."

Raya and the Last Dragon

Lots of Disney films have switched directors, but "Raya and the Last Dragon" might take the record for the latest announcement for such a change. Don Hall and Carlos López Estrada were confirmed as the film's new directors, replacing Paul Briggs and Dean Wellins, in August 2020 — only seven months before the film's hybrid theatrical/Disney+ release (Briggs retained a co-director credit). On top of that, the heroine Raya was recast, with Kelly Marie Tran replacing Cassie Steele. Qui Nguyen ("Crazy Rich Asians") also came aboard to perform some rewrites.

The reasons for these changes had a lot to do with reworking Raya's personality from a stoic type to a more light-hearted character. Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter, Hall revealed that they wanted her to be more like "Star-Lord from 'Guardians of the Galaxy' in terms of having a little of that swagger." The film also used to be a lot darker: Namaari was a more traditional villain; there were discussions over whether or not the dragons should come back to life; and the action was way more intense. "There may have been some things that if we were to include [them] would give us an R rating for violence," Estrada told Empire magazine (via The Disinsider). "There is a cut of the movie with broken bones and stuff."

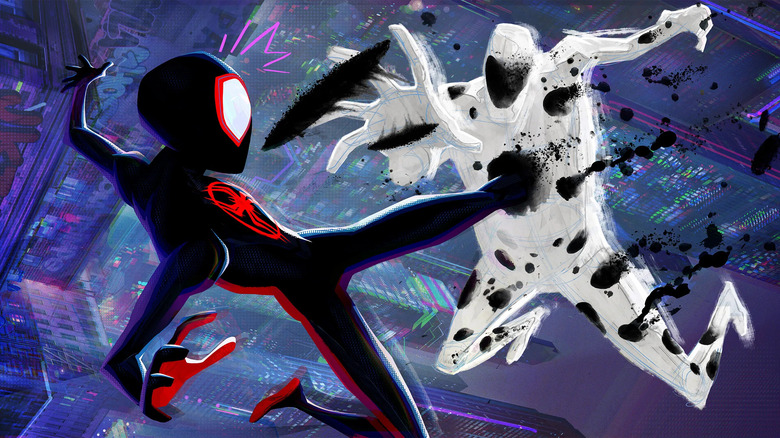

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

The quality of the animation in Sony's critically acclaimed sequel "Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse" is astounding, but the story of how this amazing film was produced has cast a shadow over it. According to several anonymous sources interviewed by Vulture, the movie remained incomplete weeks before its release, with producer Phil Lord being extremely indecisive and requesting that fully-rendered shots be redone over and over.

This process of constantly revising up until the last minute is part of Lord and creative partner Christopher Miller's general working practice according to the insiders that Vulture spoke with. "They'd come in and start to rewrite lines, throw out entire sequences, throw out animations all over the place, everywhere," the animator said. "And this is animation that people have been working on for a long time."

While animated films are often subject to big last-minute changes, the animators who contributed to the Vulture piece specifically objected to the fact that these changes were being requested on finished animation rather than during storyboards or animatics. In the end, around 100 animators ended up quitting the project due to feeling overworked.