The Untold Truth Of Good Omens

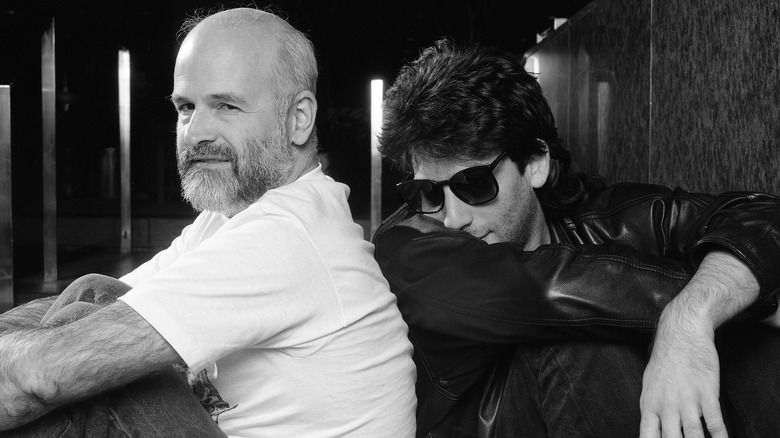

It was inevitable that a collaboration between authors Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett would become a cult classic, and that's exactly what happened with their 1990 comedic apocalypse novel "Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch." This wacky religious satire centers around the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley, who've formed a close relationship watching over humanity for millennia, working together to track down the Antichrist — an obliviously powerful boy named Adam — and prevent the end of the world.

In 2019, four years after Pratchett's death from Alzheimer's-related complications, Gaiman served as the writer and showrunner of a six-episode miniseries adaptation made as a co-production between Amazon Studios and the BBC. Starring Michael Sheen as Aziraphale and David Tennant as Crowley, the TV series was an instant fan favorite, retaining the book's sense of humor while expanding upon the world and character relationships in interesting ways. In 2023, the show's Season 2, co-written by Gaiman and John Finnemore, serves as an original sequel, and Gaiman has talked about making a third season if given the opportunity.

Whether you are familiar with "Good Omens" through the book, the series, or both, there is much more to learn about Gaiman and Pratchett's creation that you might not be aware of. Here are some of the most interesting behind-the-scenes stories and hidden details that shine a new light on this most ineffable story.

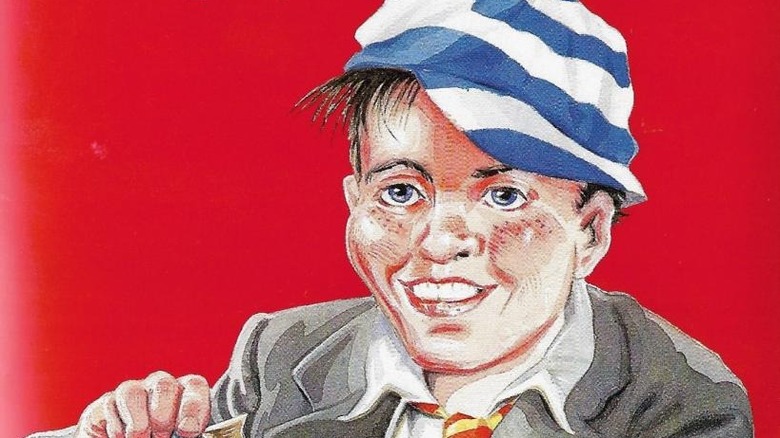

Good Omens originated as a parody of the Just William series

According to the afterword of the Harper paperback edition of "Good Omens," Gaiman and Pratchett's novel was initially conceived as "William the Antichrist," a parody of the "Just William" books by Richmal Crompton. Though it's relatively obscure stateside, the "Just William" series was incredibly successful in the world of British children's literature for nearly half a century, with the troublemaking but well-meaning 11-year-old boy William Brown and his friends appearing in 38 volumes between 1922 and 1970.

Gaiman and Pratchett originally were going to have William himself raised to become the Antichrist but ended up changing the character's name to Adam so they could control the copyright. Though the general concept behind the book moved beyond a direct parody, the influence of Crompton's writing is still there in the characterization of Adam and his gang, "the Them." The "Good Omens" TV series makes a direct callout to this important influence in the first season finale, with the "Just William" books being added to Aziraphale's bookshop after Adam restores the world.

Terry Pratchett wrote more than Neil Gaiman

When two authors are co-writing a book, how much work does each individual put into the process and who gets credit for what? Gaiman's and Pratchett's accounts of the "Good Omens" writing process are in alignment with each other, so we can get a general idea of who did what for the book. Gaiman estimated, "Terry probably wrote around 60,000 'raw' and I wrote 45,000 'raw' words," but they also said they'd regularly rewrite each other's work enough that it's hard to assign specific credit to different sections.

Pratchett seconded the claim that he did most of the physical writing because of three factors: Gaiman had deadlines for "Sandman," they'd agreed that Pratchett would serve as the book's editor, and, he said, "I'm a selfish bastard and tried to write ahead to get to the good bits before Neil." The two agreed that Pratchett wrote most of the Adam/Them material and created the character of Agnes Nutter, while Gaiman focused on the Four Horsemen and many of the tangential asides. Ultimately, their collaboration was so strong that Pratchett credited much of the book to "a composite creature called Terryandneil."

A bad review became great marketing

Upon publication in the United Kingdom in 1990, "Good Omens" was an instant hit, earning strong sales and positive reviews. In the United States, it took a bit more time to find an audience and struggled due to an extremely negative review in The New York Times. Workman, the first American publisher, dropped the book in response to the pan, not giving it promotion and heavily discounting the remaining copies.

In retrospect, this review was dreadfully wrong — and not just about "Good Omens." In it, critic Joe Queenan also dismissively described the band Queen as "a vaudevillian rock group whose hits are buried far in the past and should have been buried sooner" and said Douglas Adams' "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" is "a vastly overpraised book or radio program or industry or something that became quite popular in Britain a decade ago when it became apparent that Margaret Thatcher would be in office for some time and that laughs were going to be hard to come by."

Of course, outside the context of a critic disliking both, comparing "Good Omens" to a beloved classic of sci-fi comedy like "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" would sound flattering. Reissues of "Good Omens" have turned a review that initially hurt the book into a means of promoting it; the covers now quote The New York Times in calling it "a direct descendant of 'The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.'"

One interviewer thought it was real prophecy

Here's a request for any lost media hunters who might be reading this piece: Please try to find a recording of Gaiman and Pratchett's most ridiculous press interview from the 1990 "Good Omens" book tour. Based on Gaiman and Pratchett's many recollections of this interview with a New York ABC radio affiliate, it's almost certain to be as hilarious as any of the funniest bits in "Good Omens" itself.

The thing that made this interview so memorable — so much so that Pratchett could perfectly recall the details even when he was losing his memory from Alzheimer's — is that the interviewer had not actually read the book and did not realize it was a work of fiction. "He thought he'd been given two kooks who'd come across these old prophecies and were predicting that the world was going to be ending," Gaiman told the science fiction magazine Locus, to which Pratchett added, "Once we realized, it was great fun. We could take over the interview, since we knew he didn't know enough to stop us." The engineers, visible to the subjects but not the interviewer, were apparently falling over with laughter in the control room.

Two different movie versions failed to come about

Long before the Amazon Prime streaming series became a reality, Hollywood had its eyes on "Good Omens." Two different movie adaptations are known to have been in development but never came to be. The first, from 1992, had a script that was written by Gaiman but involved significant changes from the book at the behest of the studio, Sovereign Pictures. The worst of these changes, according to those who've read it, was that Crowley was much meaner to Aziraphale. When asked about this on Tumblr, Gaiman answered, "He was the Crowley that the studio wanted, in the story they wanted." Sovereign Pictures ultimately went bankrupt, putting the script in legal limbo.

The second Hollywood go-round in the early 2000s seemed more promising. Terry Gilliam, whose "Monty Python" humor and dark fantasy films were clear influences on Gaiman and Pratchett's sensibilities, was going to direct it. Robin Williams was rumored to be the top choice to play Aziraphale, with Johnny Depp talked about as a potential Crowley. Gilliam had big ideas for how to adapt the book that earned the authors' approval. Alas, the combination of budget and runtime restraints, discomfort with apocalyptic stories in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and Gilliam's generally busy schedule kept this adaptation from coming to fruition.

How Gaiman's Judaism influenced Crowley

As a Jewish person who went to a Christian school and has family in Scientology, Gaiman has a unique perspective on religion, to say the least. "Good Omens" is a story set firmly within a Christian mythos, but Gaiman's Jewishness still heavily influenced it. This is most notable in regard to the character of Crowley, whom he's called on Tumblr "the most Jewish character I've ever written."

Why is Crowley so widely interpreted through a Jewish lens? On the most basic level, it's because he's always questioning the operations of Heaven and Hell, and Judaism is a religion based on questioning (the Hebrew word "Israel" translates to "wrestles with God"). His perspective on his demonic duties is closer to the Jewish conception of Satan as testing humanity than the Christian conception of Satan as evil. "Good Omens" as a whole draws influence from the Jewish tradition of midrash — stories that elaborate upon the Bible in sometimes wild and conflicting directions. Gaiman wrote on Tumblr, "You can't be familiar with the midrash and also assume that anyone in the Bible has any idea what's actually going on."

The show had to change Crowley's car

In the book, Crowley drives a 1926 Bentley — a model neither Gaiman or Pratchett had ever actually seen. "It was in the days before Google," Gaiman explained to Business Insider. "[A] '26 Bentley, that sounds right." When it came time to visualize the car, however, the real 1926 model didn't actually fit with the image in Gaiman's head, so a 1933 Bentley ended up being used for the TV series instead.

Cars of this era had their limitations, so the stunt sequences where Crowley drives at 90 miles per hour couldn't be done with the real Bentley. As such, many scenes used CGI, constructed models, or rear projection effects instead of real driving. The scene where the car is set on fire and blows up, however, was done for real with practical effects. "Yeah, so, there were many Bentleys," director Douglas Mackinnon said of the scene.

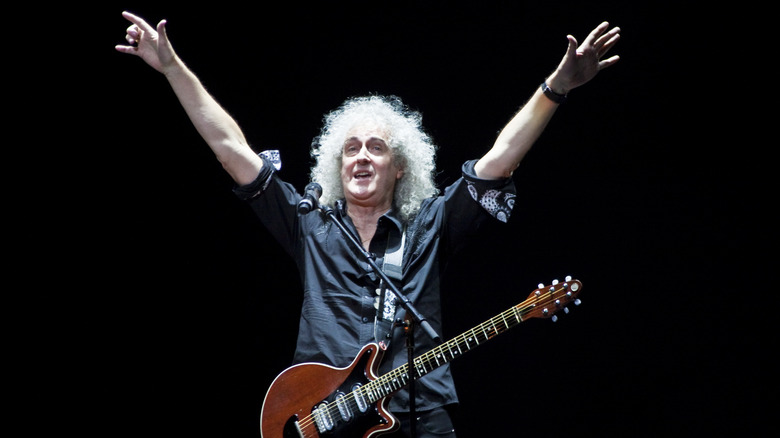

Brian May took convincing to license the music

In the novel, Crowley's introduction in the present day reads as such: "Nothing about him looked particularly demonic, at least by classical standards. No horns, no wings. Admittedly he was listening to a 'Best of Queen' tape, but no conclusions should be drawn from this because all tapes left in a car for more than about a fortnight metamorphose into 'Best of Queen' albums." The series doesn't extend this hypothesis quite so wide, but all music played in Crowley's Bentley at least does become "Best of Queen."

Queen's lead guitarist, Brian May, was initially skeptical about whether this joke was loving or mocking, and as such he refused to license the band's music for the BBC radio adaptation of "Good Omens." When it came time for the TV adaptation, however, this music had to be included, so Gaiman wrote May a letter, Gaiman said on Tumblr, explaining the origins of the book's cassette tape joke and how much he and everyone involved with the series loved Queen's music. May apologized for his initial reluctance and licensed the band's catalog to become the soundtrack to the show, though he took a little extra convincing to let them use "Bohemian Rhapsody" due to the biopic of the same title being made around the same time.

Lots of Pratchett Easter eggs

Though Pratchett sadly didn't live to see the "Good Omens" TV show get made, his presence is felt throughout the series. Not only does it faithfully adapt the spirit of his writing, but the production team included multiple Easter eggs in tribute to the beloved comedic fantasy writer. One notable such Easter egg is that Pratchett's signature fedora and scarf are on display in Aziraphale's bookshop. "We never focus on it," cinematographer Gavin Finney told SyFy Wire. "It's just there, and the camera goes past the hat and scarf. It was cool not to foreground it, but just to have it in the background." Pratchett's books are also included in the shop's extensive not-for-sale collection.

Pratchett himself was originally set to make a cameo, and there's still a voice cameo from someone playing Pratchett ... sort of. In Episode 4, the nuclear power PR person on the radio is voiced by "Game of Thrones" actor Paul Kaye, who played Pratchett in the reenactments for the BBC documentary "Terry Pratchett: Back in Black" and used the same vocal impression for "Good Omens." This is a fitting place to pay homage because before he began writing "Discworld," Pratchett had worked in the press office for the Central Electricity Generating Board in an area with multiple nuclear power plants.

Michael Sheen keeps up with fan art and fanfic

People who make TV shows don't typically pay attention to fan fiction. Some are uncomfortable with it, while others (including Gaiman himself) are supportive of people writing it but avoid reading it themselves for legal reasons. Occasionally, however, you'll find a creative who's a bit more involved with the sphere of fan works, and Aziraphale actor Michael Sheen is one such person.

Sheen has cited fan fiction as part of why he chose to play up Aziraphale's romantic attraction to Crowley. On "The Graham Norton Show" in 2021 (via Tumblr), Sheen said, "There's a lot of fan fiction going on out there. ... It's kind of amazing. I think it's a fantastic thing — the fact that people sort of were a bit weird about [fan fiction] ... I think it's wrong — [fan fiction is] such a love of the show, and it shows such commitment to it. I think it's wonderful." He's regularly shared and praised "Good Omens" fan art on Twitter, which has significantly endeared him to the fandom.

A petition asked Netflix to cancel the Prime series

Despite its highly irreverent attitude towards Christianity, the book "Good Omens" was met with shockingly little backlash from the religious right and was embraced by many progressive Christians. The TV series, however, had a bigger platform with more publicity, and with that mainstream presence came negative attention from the Catholic conservative group the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property. This organization got over 20,000 signatures on a petition to ban the "blasphemous" series — and addressed this petition to the wrong streaming service entirely.

The petition, which complained about everything from the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse being a biker gang to God being voiced by Frances McDormand, was wrongly addressed to Netflix. Netflix had nothing to do with the production or distribution of "Good Omens." Netflix's U.K. Twitter account humorously responded, "Ok we promise not to make any more," while Amazon Prime Video's Twitter joked, "Hey @netflix, we'll cancel 'Stranger Things' if you cancel 'Good Omens.'" The petition corrected its mistake after being widely mocked, but it certainly didn't stop Amazon from ordering a second season.

Season 3 could deliver on Pratchett's sequel plan

As of this writing, a third season of "Good Omens" has yet to be officially greenlit. However, Gaiman said that he's planning a potential Season 3 of the TV series to adapt the story for the book sequel he and Pratchett planned out but never got the chance to write. The book "Good Omens" was written just before Gaiman's "Sandman" and Pratchett's "Discworld" really took off as nerd culture phenomenons. The two had brainstormed ideas for a sequel, titled "668 — The Neighbour of the Beast," shortly after the first book's publication, but after Gaiman moved to the United States and they each became fully occupied with their increasingly popular personal series, finding time together to write "Neighbour of the Beast" became impossible.

Some ideas brainstormed for the book sequel were already present in Season 1 of the show, most notably the expanded roles for Gabriel and the other angels. Season 2, Gaiman explained on his Tumblr, "Exists to get us from the end of the first book to the beginning of the second book that we plotted. If we get to make a Season 3, that is the book that Terry and I plotted in 1989." This potential Season 3, Gaiman said on Tumblr, would be intended as the series' final season.