The Ending Of Possum Explained

The following article discusses child abuse and sexual assault.

Matthew Holness' disturbing 2018 film "Possum" is hard to pin down. It's a horror movie, but with few of the jump scares or overtly supernatural elements that usually power that genre. It's a psychological thriller, but with few thrilling moments, preferring instead to creep along in a state of permanent dread. At times it feels like a British kitchen sink drama crossed with a creature feature, like some long-lost issue of "Tales from the Crypt" written by John Osborne or Harold Pinter. But as difficult as the film is to define, it is equally difficult to forget.

Based on Holness' own 2008 short story and informed by real-life stories of trauma and sexual abuse, "Possum" ends as mysteriously as it begins — what we see on screen is only part of the story. With its main character experiencing a mental breakdown, can we trust that the final confrontation between him and his wicked uncle happened the way it appears? Or that it happened at all? Or, for that matter, that any of it even happened? Could it be that every element of the film is nothing but the slow collapse of one man's fragile psyche?

Unsurprisingly, "Possum" fan theories have run rampant, with every detail — from the eerie to the mundane — combed over for clues that will unlock the mystery. Let's do a little digging of our own as we take a look at the ending of "Possum."

What you need to remember about the plot of Possum

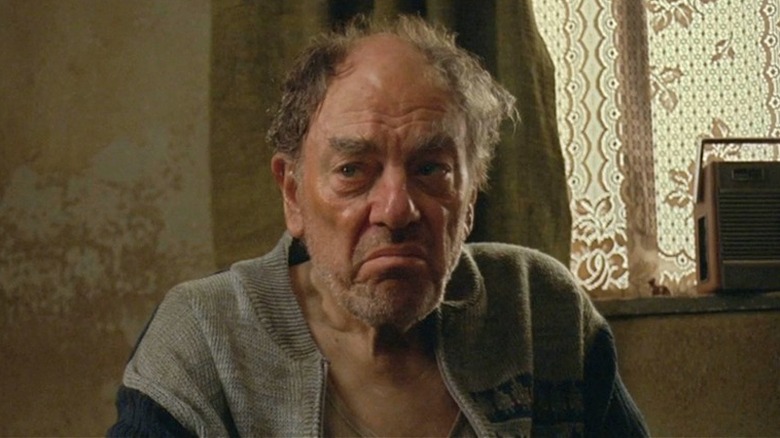

Sean Harris stars as Philip, a middle-aged puppeteer who has returned in disgrace to his Norfolk childhood home after some unnamed incident. We get scant details about what the incident might have been, things like visions of balloons choked with black smoke and a local man shouting "Pervert!" at him as he walks by. Philip's uncle Maurice (Alun Armstrong), who still lives in the filthy, dilapidated house, refers to it as a "scandal." Whatever the cause, Philip is traumatized and determined to destroy his life's work, the eponymous Possum: A hideous puppet made of thick spider-like legs and a blank plaster of Philip's own face.

The problem is that Possum doesn't want to be destroyed. Philip's attempts to abandon the puppet in the woods, or in a nearby creek, or to burn it, keep coming to naught. Possum just shows up the next day, sometimes in Philip's bed. Has the puppet somehow come to life, or is Philip in the throes of a psychotic episode? Meanwhile, Maurice taunts him nightly about incidents from his childhood, about the terrifying puppet (Maurice is also a puppeteer), and about a closed door in the house that Philip seems unwilling to enter. To make matters worse, a teenage boy (Charlie Eales) whom Philip tried to make friends with on the train home has reportedly gone missing. Philip fears not only that he might be blamed for the boy's disappearance, but that he might have unknowingly had something to do with it.

What happens at the end of Possum?

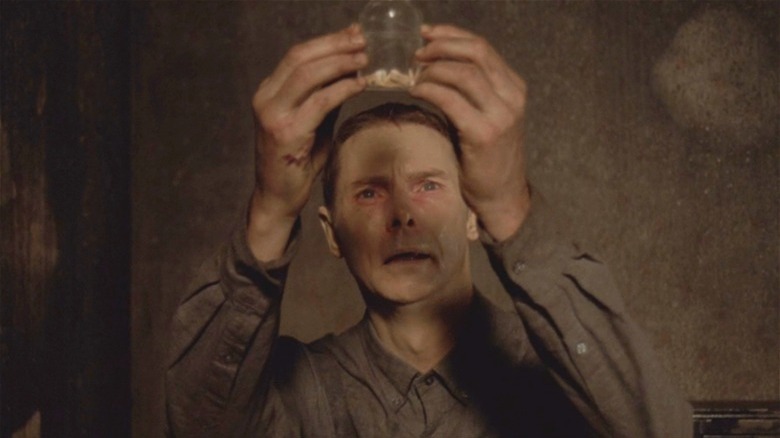

Philip retraces his steps around town to see if there are any clues about the boy's disappearance, including a frightening trip to an abandoned Army barracks where it appears that Possum is pursuing him. At home, he finally steps through the door he had been avoiding. On the other side is the remains of his parents' bedroom, still charred from the fire that killed them years ago. But while the room has gone unchanged since that awful night, it has not gone uninhabited. As Philip finds a jar full of pulled teeth, a hooded figure all in black attacks him. It's Maurice, who admits to being the boy's abductor and attempts to molest Philip in the same way he would do when Philip was a boy.

It's a harrowing scene. Philip, whimpering and begging, initially submits to his uncle's violence, but when a noise comes from a large trunk in the room, he realizes that the boy is still alive. Philip overpowers Maurice and snaps his neck on the room's broken floorboards. He opens the trunk and the boy flees without a word. Alone, Philip sits on the stoop in his backyard, smoking a cigarette. In the distance we see the spindly legs of Possum sitting in a rubbish heap. Is Philip no longer haunted by his ghastly creation, or are there some things that can never be cured, only lived with?

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

Cutting the strings

A sense of mysterious but familiar dread is baked into "Possum." Holness' 2008 short story was written for a Comma Press horror anthology titled "The New Uncanny," with entries based around Sigmund Freud's theories of the uncanny — childhood fears and fantasies that seep into the adult world. "They asked all the writers [of the anthology] to read Freud's theory of the uncanny," Holness told Screen Mayhem in 2018, revealing that they were all told to "pick a fear that appealed and write it for a modern audience." Holness selected two different fears — of dummies and of doubles — and combined them, seizing on the idea of a puppet that is a double of its puppeteer. But rather than being an exact physical match like the well-worn trope of a creepy ventriloquist dummy, the puppet is made to resemble the man's twisted inner life, born of horror and trauma.

The film version of the story delves even deeper into the waters of puppets, doppelgangers, dreams, and nightmares. Everyone Philip comes into contact with is his double in some way: The teenage boy, seen drawing in a notepad just as young Philip once did; Possum itself, which wears Philip's face as its own; and Maurice, also a puppeteer and someone who seems to know Philip's secrets (such as the location of his Possum sketchbook) without being told. Philip is very much Maurice's puppet throughout the story, and when he manages to break the child molester's neck at the end of the film, he's essentially cutting the strings.

Are there supernatural forces at work?

In a literal reading of the film, "Possum" is a supernatural tale of a puppet who is pushing its creator toward a reckoning with his abusive upbringing, despite the creator's attempts to destroy it. But the film resists such a literal interpretation. Possum's many returns are only ever witnessed by Philip himself, and several other disturbing moments — like the black rain that falls from the sky as he looks at an old picture of his parents — are likewise limited to his point of view, suggesting that they are fantasies or waking nightmares.

But if Possum is not actually alive, that would mean that the many scenes of Philip trying to get rid of the ghastly thing are not really happening, or at least not happening the way the film shows us. And if so, can we be confident that any of what we see exists beyond Philip's fraying psyche? For instance, no other characters but Philip ever see or interact with Maurice, who is confined to the broken down home that they share. The television reports of the boy's disappearance seem to drift in and out of reception on Philip's TV, and the fact that the boy who disappeared is the exact one that Philip tried to speak to on the train seems too unlikely to be a coincidence.

If every other character acts as a double or doppelganger to Philip, audiences can reasonably wonder if any of them were ever real in the first place. At the end of the film, when Maurice attempts to assault Philip, the protagonist overpowers and kills him. However, as there's nobody else there to see it, there's every chance that this fight is actually a mental one rather than a physical one. Philip could well be wrestling with his demons here rather than his uncle.

Possum is a part of Philip whether he likes it or not

When discussing the film's cinematic influences, Holness has often cited silent era horror movies such as Carl Dreyer's "Vampyr," sensory experiences guided by nightmare logic more so than a straight-forward narrative plot. Save for his scenes with Maurice and his creepy nursery rhyme narration, Philip barely speaks at all. His constant anguish and terror is expressed mostly through Harris' physical performance and a throbbing synth score. But while Holness' goal of creating a latter-day silent horror film is evident, "Possum" also has a lot in common with 2010s horror.

Monsters in film and literature have long been metaphors for psychological or social issues. However, the mid-2010s saw an explosion of so-called "elevated horror" that put its metaphors front and center, films like Jennifer Kent's "The Babadook," Babak Anvari's "Under the Shadow," Ari Aster's "Hereditary," and Jordan Peele's "Get Out." While "Possum" pre-dates the trend due to the original short story, the film is akin to this larger wave due to the way it makes Possum a vessel for Philip's lifetime of abuse, with the puppet a clear vessel for his trauma.

The way that Philip carries Possum around is very telling — he's always with him, but he never holds the brown bag that the puppet is in close to his body. He hates having to carry it around, but he carries it anyway. That's what makes the ending so poignant. Philip believes that he wants to get rid of Possum for good, but to remove this part of his life altogether would mean losing a part of himself. Yes, it's a dark, painful part of him, but a part of him nonetheless, and burying his trauma entirely would mean forgetting about his parents. What the ending tells us is that coming to terms with our demons is different to exorcizing them.

The real-life horror behind Possum

The specter of child sexual abuse hangs heavy over "Possum." While the plot focuses on the violence Maurice inflicted as an individual on Philip and the kidnapped boy, Holness is also concerned with the institutional cultures that let abusers like Maurice thrive. The short story explicitly sets the narrator's childhood assault near his schoolyard, suggesting that it may have been a teacher or staff member that committed it. The film is less focused on what might have happened to Philip in school, but finds a potent symbol in the town's abandoned Army barracks, where Maurice worked for years and where Philip finds himself pursued by Possum in a late scene.

Britain has faced multiple reckonings in the last two decades over sexual abuse in the military, the church, and in schools. In the early 2010s, police executed a massive sting known as Operation Yewtree, which came about after the late British celebrity Jimmy Savile was exposed as a serial rapist with hundreds of victims. "They are the monsters of our time," Holness said of Savile and other abusers in a 2018 Newsweek interview. The betrayal of trust and the culture of silence that robs victims of their voice is at the heart of Philip's trauma. With nowhere else to turn, he channeled all of his pain into the terrible, immortal Possum.

With this in mind, the final shot of the film is less ambiguous than it may initially appear. Possum's grotesque body is destroyed, but its face remains. This is Holness telling us that while Philip has managed to deal with his demons to some extent, he will still have to face his past from time to time, because some trauma simply cannot be forgotten.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

What has Matthew Holness said about the ending?

Horror may deal in frightful, fantastic situations, but in many ways it can be more realistic in handling issues of psychological damage and victimization than other genres because it has no guardrails. That's what makes it such an attractive genre for filmmakers like Matthew Holness, who opened up about the potential horror has for addressing serious issues during an interview with Newsweek. "There's always the forces of justice fighting against the evil [in order genres]," he said. "You get an in-built sense of the laws of justice. So, that's reassuring, because you know someone is fighting for good. Horror films don't necessarily have that."

While Holness may be candid about the film's influences and his desire to use the genre as a spotlight on real-life abuses, when it comes to explaining what actually happens at the end of the film, he prefers to let the ambiguity speak for itself. "There are questions that are deliberately placed in front of the viewer," he said. The answers to these questions are things that other films would consider essential details, but that's not the case here, and the ending deliberately neglects to clear things up. "There's a lot of things we don't know about Philip," Holness continued. "We don't know what this supposed scandal is that Maurice refers to. We don't know, really, whether Philip is a good or bad person."

Fan theories about the ending of Possum

Over the past few years, the film's small but dedicated fan base has taken to Reddit to pore over plot details and offer up theories about what it really means. Much of the debate centers around which of the characters actually exist and which are products of Philip's shattered mind. For many, Maurice is nothing but a malignant voice in Philip's head, a dissociative personality that allows Philip to do terrible things like kidnap the boy from the train. For others, the boy himself was not real — or at least no longer alive when Philip kills Maurice and opens the trunk. If that is the case, the boy's wordless, immediate escape after being released is nothing more than Philip's damaged mind comforting itself.

Beyond questions of who did what to whom in the film's final moments, internet sleuths have delved into some of Holness' more inscrutable imagery. Since foxes are known to play dead like opossums, does the fox in the yard indicate that Philip is somehow both alive and dead? Do the balloons reference whatever scandal happened to send him back home? Are the candies green because they are rotten? Do they cause hallucinations? And, if so, are all the horrible visions candy-induced, or just some of them? Trying to "solve" a film such as this one is fun for viewers, but in the end, all speculations are just that. As in life, sometimes there are no answers.

What have the stars of Possum been doing since?

"Possum" lingers in the mind long after it has ended, so much so that it can be easy to forget that it's just a movie, made by artists and craftspeople who go home at the end of the day. Sean Harris and Alun Armstrong are not trapped in a cage of psychosexual violence in real life. They're talented actors who have added numerous roles to their resumes since the film came out in 2018.

In addition to his recurring role in the "Mission: Impossible" film franchise, Harris has appeared in the Shakespeare adaptation "The King," the Princess Diana biopic "Spencer," and the medieval fantasy epic "The Green Knight," among others. His latest project is "The Gold," a BBC series inspired by the biggest gold heist in British history. Armstrong, meanwhile, has had regular and recurring roles on several television shows, including the Jason Momoa-led wilderness adventure "Frontier" and the parenting comedy "Breeders" starring Martin Freeman and Daisy Haggard.

When "Possum" came out in 2018, Holness said publicly that he was interested in developing the horror side of his career more. However, in the years since "Possum," he has largely returned to his funnyman roots, with guest roles on the period sitcom "Year of the Rabbit," the Matt Berry revival series "Toast of Tinseltown," and the paramedic buddy comedy "Bloods." At the time of this writing, "Possum" remains his sole feature film.