Were Oppenheimer & Einstein Friends In Real Life? What History Tells Us

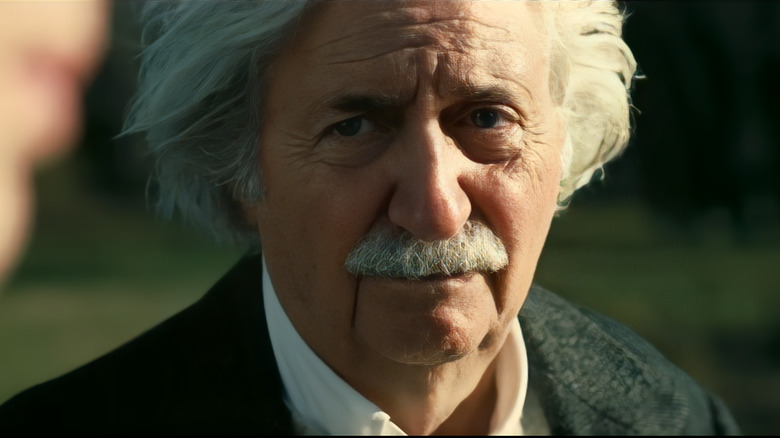

Christopher Nolan's 2023 epic "Oppenheimer" is split into three different timelines, which can be hard to follow. One character that helps ground things is the instantly recognizable Albert Einstein (Tom Conti). While he only plays a peripheral role, he and J. Robert Oppenheimer knew each other in real life, even if their relationship was a bit complicated.

In "Oppenheimer," Einstein's enigmatic presence is a boon to those trying to keep up with the film. Viewers see Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) check a set of mathematical calculations with Einstein earlier in the film, and he also has a critical conversation with Einstein by a pond at Princeton at both the beginning and end of the movie. Unfortunately, these interactions are made up. They draw from both real-life and extrapolated elements of Oppenheimer's story, repackaging them into digestible interactions with a scientist that is recognizable to almost anyone. In an interview with The New York Times (via Vanity Fair), Nolan himself explained the reason for the shift, attributing it to the fact that "Einstein is the personality people know in the audience."

It's this setup that allows the famous scientist to utter the haunting final lines of the film, "Now it's your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievement." Einstein speaks these words to his apparent acquaintance and friend, Oppenheimer. The question is, if the scenes are made up for dramatic effect, how did the pair of scientists get along with one another in real life? While Oppenheimer and Einstein's interactions may be a bit exaggerated on screen, the two men spent a lot of time close to each other later in life. In fact, they both were on the faculty at Princeton for years. Here's what we know about the historical accuracy of the apparent friendship.

Oppenheimer and Einstein were friendly enough in real life

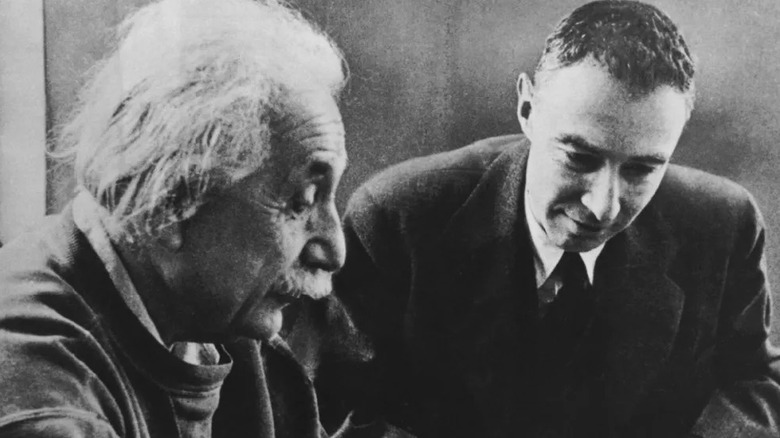

As indicated in the film, Oppenheimer served as the director of Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study. He was in this role from 1947 to 1966. Einstein was at Princeton from 1933 until his death in 1955. During this period, the two larger-than-life personalities certainly interacted. They were acquaintances and appear to have been, to a limited extent, friendly with each other, too. Multiple records show that they were, at the least, willing to complement each other publicly. Einstein even supported Oppenheimer when the latter came under scrutiny for his past communist-leaning sympathies later on in life.

Privately, there appears to have been a closeness as well. For example, in Oppenheimer's famous biography "American Prometheus," his biographers relay (via Vanity Fair) a charming, though likely anecdotal, interaction between the two men in 1948, shortly after Oppenheimer arrived on campus. The book explains, "Knowing Einstein's love of classical music, and knowing that his radio could not receive New York broadcasts of concerts from Carnegie Hall, Oppenheimer arranged to have an antenna installed on the roof of Einstein's modest home at 112 Mercer Street. This was done without Einstein's knowledge — and then on his birthday, Robert showed up on his doorstep with a new radio and suggested that they listen to a scheduled concert. Einstein was delighted."

Secretly installing an antenna on someone's roof is certainly something that goes beyond basic introductions. If there's any hint of truth to the story, it would indicate that Oppenheimer knew about Einstein's interests and cared enough about him to invest in their relationship. Even so, the connection between the two wasn't all sunshine and roses.

Generational differences created distance between the scientists

One thing that "Oppenheimer" does address is the fact that the titular character saw his eminent predecessor as a bit of an antiquated piece of scientific history. He respected Einstein's past contributions much more than his current value. In "American Prometheus," it's noted that scientists like Oppenheimer considered Einstein's stubborn refusal of newer physics as a sign that they had to move on without him. In the words of Oppenheimer himself in 1965 (via Vanity Fair), "In the last years of Einstein's life, the last twenty-five years, his tradition in a certain sense failed him."

While Oppenheimer had a bit of a "pupil surpassing the master" vibe to him, Einstein had his own qualms in the other direction. The German-born theoretical physicist respected Oppenheimer's tremendous breadth of knowledge and his personality. But he differed in many respects on scientific grounds. Einstein, for instance, didn't think black holes could exist. Oppenheimer explored their reality — partly by using Einstein's own previous achievements. The two remained at odds, scientifically speaking, for decades.

They also contributed in different ways to the pursuit of applied nuclear physics. Einstein participated in a letter sent to FDR recommending a nuclear program to counteract the German threat, but never went any further. This naturally left him with much less on his conscience than Oppenheimer. Despite the differences in scientific theory and their varying levels of contribution to the atomic problem, the two men appeared to have remained on friendly terms as they served together at Princeton.