The Ending Of Radio Flyer Explained

David Mickey Evans' script for "Radio Flyer" was a hot commodity in Hollywood in the late 1980s. The 1960s-set coming-of-age fable about a pair of boys who use the power of imagination to escape their violent stepfather was snapped up by Oscar winner Michael Douglas' production company for a record price, with Evans on board to both write and direct. By the time the film landed with a thud at the box office in February 1992, however, this Tinseltown Cinderella story had turned into a cautionary tale. The production was troubled from the very beginning: Evans was replaced as director partway through by Richard Donner, an entirely new cast was brought on, and a pair of modern-day scenes featuring Tom Hanks were shot and reshot at the last minute.

It seemed like no one, from critics to audiences to the studio's marketing team, could tell what the film was supposed to be. A poignant kids' adventure like "Hook" or "Home Alone," a domestic abuse drama like "Sleeping with the Enemy," or somehow both at once? The tonal mismatch is most glaring in its controversial ending, a literal flight of fancy that if taken literally is borderline offensive, and if taken figuratively is arguably even worse. Decades later, the film lives on in the confused memories of '90s kids who caught it piecemeal on cable TV, or perhaps were shown it by a well-meaning substitute teacher who was misled by the wholesome Americana artwork of its VHS cover. Let's take a look at the ending of "Radio Flyer."

What you need to remember about the plot of Radio Flyer

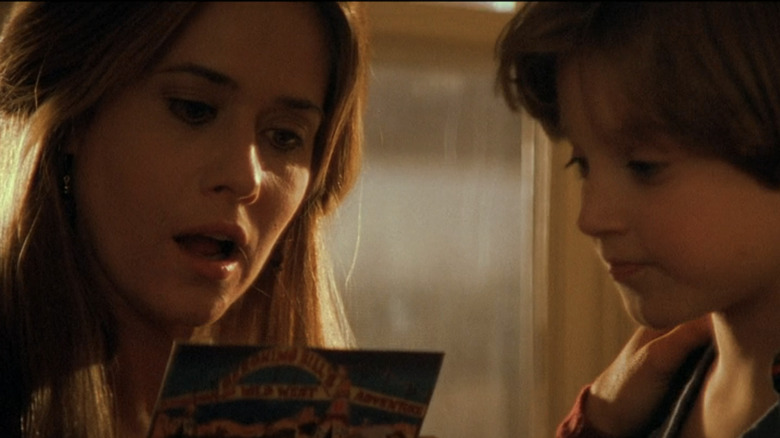

Mike Wright (Tom Hanks) sees his two sons bickering one day and tells them a story about his own childhood. In 1969, young Mike (Elijah Wood) and his little brother Bobby (Joseph Mazzello) move from New Jersey to Northern California with their recently divorced mother Mary (Lorraine Bracco) and their loyal German Shepherd, Shane. Their new home is a world of adventure for the boys, but things take a turn when Mary falls for and quickly weds a handsome charmer named Jack (Adam Baldwin), otherwise known as "The King." Behind his easygoing exterior, the King is a violent alcoholic who finds an easy target in Bobby. With their mother in the throes of newlywed bliss and unable (or unwilling) to see the truth about her new husband, Mike and Bobby seemingly have no one to turn to.

But Mike hits upon a "big idea." Years earlier, a kid supposedly took his bicycle airborne at "the wishing spot," an old barn wall turned into a makeshift ramp overlooking a small airstrip. The boys begin making a flying machine of their own out of their trusty little red wagon (the eponymous Radio Flyer), with wings made out of sheet metal and old crates, and an old table fan for an engine. The plan is to launch the Radio Flyer from the wishing spot with Bobby and Shane aboard, where they will be able to hook onto a passing plane and fly to safety. When the King attacks Bobby in a drunken rage and puts him in the hospital, the need to escape becomes even more desperate.

What happened at the end of Radio Flyer

After Bobby is hospitalized, Mary finally becomes wise to the King's true nature. But when he shows up after a brief stint in jail, hat in hand and full of promises to reform, she reluctantly takes him back. The King, however, quickly falls back into his old ways, and one night Mike and Bobby put their big idea into action. They wheel their amateur flying machine out to the wishing spot and make preparations for their maiden voyage. The King angrily pursues them, and when Mary comes home to find everyone missing, she runs to sympathetic local cop Ben (John Heard) for assistance.

The King finds the boys just as they are about to launch. Shane leaps from the craft and bites him, and the passing wing knocks the drunken lout unconscious. The makeshift plane rattles down the hill, gaining speed, until it hits the ramp and miraculously goes airborne. Bobby, via walkie-talkie, makes Mike promise to look after their mother, as he and the Radio Flyer soar through the night sky, never to be seen again. Ben arrests the King. Mary, understandably, can't believe that Bobby actually flew away — that is, until Bobby mails a postcard home, revealing that he is safe and has joined up with Geronimo Bill's (Ben Johnson) traveling Wild West show. In the modern day, Mike imparts to his sons that history is told from the teller's perspective and that once a promise is made, it lasts forever.

So, did he fly...?

There are several ways to interpret the film's ending, specifically Bobby's successful flight aboard the Radio Flyer. The first way, which is the simplest yet hardest to believe, is that everything happened exactly the way it is shown: Mike and Bobby drew up blueprints for a flying wagon with crayons and colored pencils and they built the craft out of spare parts and old junk. They then successfully gained enough speed going off the wishing point to get airborne, and Bobby, despite being eight years old with little to no aeronautic training, was able to not only pull the craft out of tailspin at a climactic moment but pilot it through the night to places unknown.

This is what we see happen in the film, with nothing but our grown-up incredulity to tell us otherwise. And the film even attempts to head this objection off at the pass via adult Mike's narration, telling us that his mother couldn't believe that Bobby actually flew away because she had lost the childhood perspective that makes magic real. The script's so-called "seven great abilities and fascinations" posit that if a child believes in something, that belief makes it literally so. Thus, monsters are real, animals can talk, blankets provide an impenetrable shield, and kids can fly — but only if they believe that they can. When Bobby takes off from the wishing point, it's meant to evoke the same wonder as the flying bicycles in "E.T.," another film in which the purity of childhood is conjured in magical terms.

...or did he die?

But "E.T." had a catalyst for its literal flights of fancy: E.T. himself. "Radio Flyer" not only has no external source for its fantasy elements, but undercuts its own magical thinking for most of the film. The monster that scares them in the dark is just their dog Shane. Fisher, the boy who flew his bike off the wishing point, was left severely injured by the resulting fall. Despite Hanks' ending narration, there is little leading up to the climax to make us believe that the magic of childhood is a literal power in this universe. So as young Mike stares off into the heavens and Mary frantically asks him where his brother is, we can most logically assume that Bobby did not fly away to Geronimo Bill's Wild West show, but rather plummeted off the wishing point to his death.

That is an incredibly bleak interpretation, so sudden and heartbreaking that it becomes almost darkly comic. Donner lingers perhaps a little too long on that moment between Mike and his mom, and the sincerity of Bracco and Wood's performances — Mike's childlike confidence versus Mary's mounting adult panic — do little to assuage the feeling that something awful has happened.

An unreliable narrator

The rest of the epilogue tries to sell the idea that Bobby really did fly away, and that he lived the rest of his life traveling the globe — presumably still in the Radio Flyer — sending postcards to his family at various stops along the map. But the film can't help but undercut itself one more time, as the camera returns to adult Mike telling this story to his sons. "You remember what I said about history being in the mind of the teller?" he asks them, and as they nod he replies, "Good. Because that's how I remember it."

That small admission opens the floodgates to any number of readings, each more grim than the next. Did Bobby fly that night, or did he fall to his death? Or was the "big idea" of the flying Radio Flyer in itself a coping mechanism for Mike to deal with the death of his brother at the hands of the King? Is the drastic nature of the boys' plan, to save Bobby from the King's abuse by sending him away forever, a metaphor for suicide? Or, considering that this is evidently the first time Mike's sons are hearing about their uncle, is it possible that there never was a Bobby, and that Mike has reconciled his own childhood abuse by projecting it onto a little brother who never existed? If "Radio Flyer" has a legacy three decades later, it is in the Reddit boards and video essays attempting to parse the ending for some sort of concrete meaning.

1-800-4-A-CHILD

While elements of the ending may be imaginary, the kind of domestic violence depicted in the film is all too real — a fact the film acknowledges by listing the number for Childhelp's National Child Abuse Hotline, 1-800-4-A-CHILD, just before the end credits roll. Originally founded as an adoption agency in 1959, Childhelp expanded its mission over the decades to include welfare and advocacy for all children suffering from abuse and neglect. In 1982, the organization established its 24-hour national hotline, which is still in operation today.

In addition to listing the hotline number, there is another message on screen: "Today there is help." The film's mid-century setting taps into the same nostalgic feelings that helped make movies like "Stand By Me," "Mermaids," and "My Girl" into recent hits. But placing it in 1969 wasn't just a nod to Baby Boomers: It was a reminder of the ways that society has changed for the better in the last few decades. The '60s saw incredible shifts in nearly every aspect of American society, including the ways that child abuse and neglect are handled by doctors, educators, and law enforcement. By the mid-1970s, every state in the country had mandatory reporting laws, and the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act provided federal funding to Child Protective Services from coast to coast. Bobby makes his escape on the Flyer because his mother can't see the truth of the King's violence, and he and Mike feel they have nowhere else to turn. That wouldn't be the case just a few years later.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

Critics did not go along for the ride

While flashing a child abuse hotline number over the end credits may have been well-intentioned on the part of Evans, Donner, and Columbia Pictures, for many critics, it was one last ploy in a deeply cynical film. Reviews were almost uniformly negative in 1992, and if the film's current 35% rating on Rotten Tomatoes doesn't seem that bad, it is only because of the site's at-times questionable judgment as to what constitutes a positive review. Empire Magazine's 2000 appraisal is given a tomato marking it as favorable, despite the author calling the film "puzzling" and "borderline distasteful."

For other critics, there was no "borderline" to its distastefulness, especially when it came to the film's ending. Roger Ebert's one-and-a-half-star review spends a lot of time pondering what could have been going through the minds of the film's talented creators and financial backers as they filmed a climax that involved a boy racing down the hill, likely to his death. "I was so appalled ... that I didn't know which ending would be worse. If he fell to his death, that would be unthinkable, but if he soared up the moon, it would be unforgivable — because you can't escape from child abuse in little red wagons." Ebert interpreted the ending as being a metaphor for Bobby's death, as did Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman, who wrote that "Bobby's 'victory' is so literal, so bathed in free-floating Spielbergian wonder, that the movie seems to lose its mind."

What have the filmmakers said about the ending?

A quick perusal of the film's coverage, from contemporary reviews to modern-day investigations by traumatized millennials, gives the sense that just about everyone thinks Bobby dies going off the wishing point. Even the film's composer, Hans Zimmer, said as much in an interview with Soundtrack Magazine a few months after its release. Donner, speaking to Entertainment Weekly for a postmortem of the film's troubled production, wanted the ending to be ambiguous, but understood how it might confuse and upset audiences. "If I could have stood up in every theater in front of every audience, I could have explained it," he said.

One person who very much believes in the film's ending as it's literally shown, however, is screenwriter David Mickey Evans. Over the years he has maintained that the ending is meant to be interpreted exactly as it was shown in the film, that Mike and Bobby built a flying machine out of a Radio Flyer and that Bobby flew it to safety. In an interview with journalist Stephen Greenfield (via Evans' personal blog), he said that "the Radio Flyer is a metaphor, it worked in the vastness of childhood imagination, and because of the 100% belief the kids had in it, it worked in reality-reality as well." The interview also notes there were fantastical elements cut from the final version of the film that would have shored up this notion, such as Mike and the boys' dog Shane being able to communicate with each other.

Radio Flyer's alternate ending

One of the major changes made from Evans' script was the final scene. Returning to the present day, Mike was originally going to take his sons to the National Air and Space Museum, where they see the Radio Flyer on display — floating magically in the air — next to the Wright brothers' plane, and where Mike reunites with Bobby, now an Air Force pilot. This original coda was cut after test audiences found it confusing, and was eventually replaced with the framing device of Mike telling the story of Bobby and the Radio Flyer to his sons. This also resulted in the film having two different prologues, one setting up adult Mike and his kids followed by a black-and-white sequence telling the legend of Fisher and the wishing spot.

The original ending would have put to rest any suggestion that the Flyer was a metaphor for Bobby's death or anything else — or at least that's what Evans has maintained for years. Two decades after the film was released, however, Evans gave himself the chance to prove it. "Radio Flyer" had begun life as a short story titled "Robert Radio Flyer, the King of Pacoima" before becoming a film script, and in 2013 Evans expanded that original story into the self-published novel "The King of Pacoima." Illustrated with old photos and kodachrome slides from his youth, the novel recaptures not just the autobiographical aspects of the story for Evans, but also the magic realist elements, including the ending, that were pared away from the film.

What have the cast and crew of Radio Flyer been up to?

The ordeal of "Radio Flyer," from its contentious production to its commercial and critical failure, might have broken the spirit of many a young filmmaker. Evans, however, didn't have to wait long for his second chance at Hollywood glory: Just a year later he wrote and directed a much more well-received nostalgic family film, the 1993 baseball classic "The Sandlot." Since then he has made a steady career for himself, helming family flicks like the Matt LeBlanc-and-chimp sports movie "Ed," sequels to "The Sandlot," "Ace Ventura, Pet Detective," and "Beethoven." Richard Donner, meanwhile, was already a legendary director in 1992, and was in the thick of his mega-popular "Lethal Weapon" series when "Radio Flyer" crashed and burned. His last film was the 2006 Bruce Willis thriller "16 Blocks."

The film likewise could have been a career-killer for its young cast, but luckily their successes overshadowed its failure. In 1993 Mazzello played dino-loving know-it-all Tim in Steven Spielberg's "Jurassic Park," while Wood was in the midst of an incredible run that included lead roles in "The Good Son," "The Adventures of Huck Finn," and the notorious Rob Reiner flop "North." Both actors successfully made the leap from child to adult roles as well. Lorraine Bracco found her signature role at the end of the decade as Dr. Jennifer Melfi on "The Sopranos," while Baldwin remains an in-demand television and voice actor. Tom Hanks, sadly, faded into obscurity after "Radio Flyer" tanked, and like young Bobby, was never heard from again – unless you count his back-to-back Oscar wins in 1994 and 1995, that is.