The Demeter's Dracula Is The Scary Vampire We've Been Craving & Society Needs Now

At the mouth of River Esk on England's eastern shore lies the seaside town and port of Whitby. Home to the gothic ruins of Whitby Abbey and the Church of Saint Mary, Whitby is where actor and theater manager, Abraham "Bram" Stoker, became inspired to turn his recurring nightmare into one of horror's most famous novels of all time: "Dracula."

While vacationing in Whitby in the summer of 1890 — as Christopher Frayling recounted in "Nightmare: The Birth of Victorian Horror" — Stoker "heard a strange story about a Russian schooner called the Dmitri. Five years earlier on October 31st, the ship ran into the harbor amidst a storm, with all sails up, and narrowly avoided the rocky shore." According to Time, "the ship, which originated in Varna, an eastern European port, was carrying a mysterious cargo — crates of earth." On that same summer vacation, Stoker noted that "Dracula in the Wallachian language means Devil [and is-was used as a surname for] any person who rendered himself conspicuous either by courage, cruel actions, or cunning."

Stoker integrated the Dimitri's story into his novel, renaming the ship the Demeter and making its miraculously unmanned arrival responsible for how Dracula reached England. Though this part of the vampire's journey is only briefly covered — in a chapter entitled: "Cutting From 'The Dailygraph,' 8 August" – it's still integral to understanding the novel's lesser explored themes. Nearly 130 years after its publication, this fateful voyage is vital to unpacking the novel's discussions of racism and xenophobia. Director André Øvredal's unique adaptation of that journey, "Dracula: The Last Voyage of the Demeter," is a timely reminder of how "Dracula" spoke to the then-fearful anxieties of Victorian England that sadly still echo into today's contemporary society.

Listen, we love sexy vampires, but...

To an even greater degree than his predecessor, Lord Byron, Stoker forever changed the popular understanding of the vampire. By making his titular character a foreign aristocrat and foregrounding themes of seduction, transition, penetration, liberation, temptation, and resurrection, Stoker's bodily fluid-filled novel took a common bit of transcultural folklore — one born from a lack of knowledge about the process of decomposition and illnesses — and turned it into something else entirely. "Dracula" is nothing if not one big, bloody, euphemistic, and overtly Freudian romp through Stoker's and surrounding cultures' fears, phobias, repressions, taboos, and anxieties.

The 20th and 21st centuries have brought audiences a litany of culturally relevant iterations of Stoker's monster — everything from coming-of-age romances ("Twilight," "First Kill"), to a failed civil rights allegory ("True Blood"), to a sweet yet complicated story of love and duty ("Let the Right One In"), to adaptations that successfully explore issues of identity, inequality, oppression, acceptance, liberation, interpersonal relationships, co-dependence, and transformation using everything from gothic literary tradition and American history ("Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire") to gut-busting humor and mockumentary interviews ("What We Do in the Shadows").

But while almost every Dracula movie has employed the novel's more obvious subtext — homoeroticism, tension with sexual liberation, and potential to serve as a metaphoric vehicle for transitional states of being — via all kinds of vampire narratives, few have viewed Dracula himself through quite the same lens as his Victorian-era creator. Even adaptations of the novel, such as 1992's "Bram Stoker's Dracula" and Netflix's "Dracula," have stopped short of making their simultaneously alluring and deadly Dracula something to fear. In that aim, they've avoided — almost entirely — the novel's xenophobic core. Unfortunately, 2023's atmosphere warrants as much of our attention as ever on exploring our fear — and hunting — of the Other.

...Stoker's Dracula is more than a sex symbol

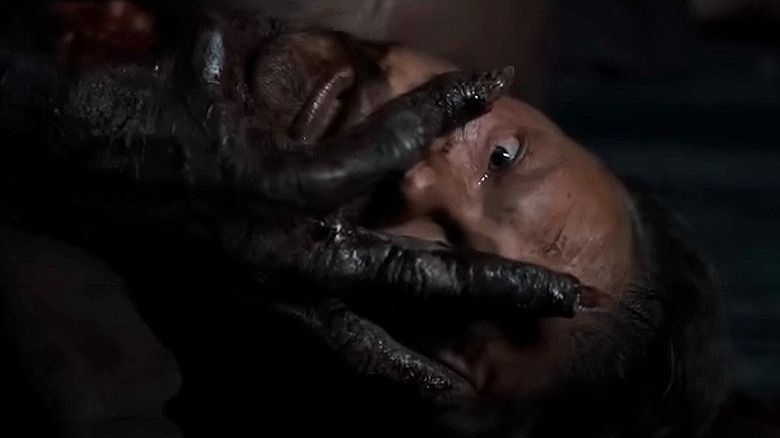

In fleshing out the chapter in Stoker's novel that highlights the notion of immigration as "invasion," "Dracula: The Last Voyage of the Demeter" has woven this Othered theme back into Dracula lore. That Øvredal and writers Bragi F. Schut and Zak Olkewicz chose to make their monster animalistic and terrifying (rather than sexy), their atmosphere claustrophobic and unsettling (rather than decadent and stylish), and their victims doomed (rather than repressed and then empowered) strengthens the film's determination to portray the story as it was originally intended.

As Stephen D. Arata's "'Dracula' and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization" stated:

"Dracula appeared in a Jubilee year, but one marked by considerably more introspection and less self-congratulation [...] Late-Victorian fiction, in particular, is saturated with the sense that [England] — as a race of people, as a political and imperial force, as a social and cultural power — was in irretrievable decline." Arata notes a number of contributors to this sense of decline (and the push back against it) including, most importantly, a "growing domestic uneasiness over the morality of imperialism." Much of the country was beginning to question the Empire's history of subjugation and oppression, while others simply feared — for obvious, if subconscious reasons (aka, "the anxiety of reverse colonization") — the influx of immigrants from a variety of places, including Eastern Europe. This anxiety rose to the surface in Victorian literature, since, as Arata observes, "fantasies of reverse colonization are more than products of geopolitical fears. They are also responses to cultural guilt. In the marauding, invasive Other, British culture sees its own imperial practices mirrored back in monstrous forms."

Unfortunately, this doesn't mean that culture magically embraces said Other. Though their arrival may be seen as a "deserved punishment," it is still seen as a punishment — a source of fear and a vessel for rebuke. What does all this have to do with Dracula, Øvredal's film, and what both have to teach us in 2023? Everything.

The Last Voyage of the Demeter brings Stoker's monster back

For those unfamiliar with Stoker's "Dracula," the gist of Chapter 7 revolves around a newspaper clipping in Mina's journal that tells of a massive, unnatural tempest and a mysterious shipwreck in Whitby. Like the Dmitri, the ship miraculously makes its way into the harbor. However, everyone on board is dead, and a corpse is tied to the helm. The reporter (aka "your correspondent") is permitted access to Demeter's logbook, and from the captain's entries, we learn of a pervasive evil aboard the ship. One by one, men disappear or grow increasingly distressed and paranoid. One throws himself overboard. From the first captain's entry, we learn the ship's cargo is mostly "boxes of earth." His final entry reads, "... In the dimness of the night, I saw It—Him! ... I shall tie my hands to the wheel when my strength begins to fail, and along with them I shall tie that which He —It!— dare not touch ... I shall save my soul..."

Øvredal takes the Demeter's journey and remains faithful to the information contained in the newspaper report and the captain's log. On the surface, what unfolds is a tale not dissimilar to John Carpenter's "The Thing." A group of people living in extreme isolation are confronted with a shapeshifting enemy against which they have no real defense. But unlike "The Thing," there's no ambiguity here: Dracula alone survives this claustrophobic confrontation. Relevantly, Dracula isn't simply bringing himself. He's bringing his homeland (literally, boxes of it). As Arata noted, "He is in effect his own species ... Dracula can himself stand in for entire races, and through him, Stoker articulates fears about the development of those races in relation to the English."

Øvredal chose his chapter wisely

Stoker was hardly reinventing the symbolic wheel when he imagined his invading contagion coming from abroad on a ship. Medieval mythology is rife with ghost ships bringing plague from other countries, partly because the disease really did follow overseas trade routes, and partly because the personification of disease provided a convenient explanation in the absence of a scientific understanding. Xenophobia and paranoia often led these narratives to take things a step further. In "Ships, Fogs, and Traveling Pairs: Plague Legend Migration in Scandinavia," Timothy R. Tangherlini explained that a plague in these stories is "often brought by a foreigner to the community. Rather than acting as a personification of the plague, these foreigners are the cause of infection ... In Sweden, the foreigner is a Finn; conversely, in Finland, the foreigner is a Swede." A person becomes representative of and the target of society's woes.

Sometimes, those woes are a literal disease. Sometimes (as in the late-Victorian era), those woes are a shift in global influence, a reluctant reexamining of the past, immigration and the growth of other cultures, or social progress that threatens — or rather, is seen as a threat to — the status quo (e.g., The New Woman, as represented by the free-spirited Lucy in "Dracula"). In Stoker's novel, the Demeter acts as a microcosmic warning of things to come in Great Britain.

By remaining true to Stoker's version of Dracula's disastrous journey to his new home — and allowing us to get to know, sympathize with, and root for doomed characters who are little more than names or nameless references in Stoker's chapter — Øvredal forces us to engage with the literal side of Stoker's metaphoric "invasion" by the Other.

A scary Dracula is a relevant one

Experts in 2016 told the United Nations Social, Humanitarian, and Cultural Affairs Committee that racism and xenophobia were increasing globally (via UN Press). Four years later, Human Rights Watch reported on "Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide," citing several examples of it in various countries. They also noted an increase in Sinophobia and Anti-Asian sentiment, stating: "Several political parties and groups, including in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Greece, France, and Germany have also latched onto the Covid-19 crisis to advance anti-immigrant, white supremacist, ultra-nationalist, anti-semitic, and xenophobic conspiracy theories that demonize refugees, foreigners, prominent individuals, and political leaders."

In 2022, an NPR poll found that "more than half of Americans say there's an 'invasion' at the southern border [and] large numbers of Americans hold a variety of misconceptions about immigrants — greatly exaggerating their role in smuggling illegal drugs into the U.S., and how likely they are to use public benefits, for example." Additionally, the U.S. is seeing an increase in anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric, organized activism, and misinformation campaigns (per Just Security). In 2023, a record-breaking number of anti-LQBTQ+ bills have been introduced in the U.S. (per CNN).

This ongoing uptick in xenophobic beliefs and bigoted misconceptions and the promotion thereof by prominent politicians is happening at the same time that, by contrast, many in the United States are attempting to more openly process and investigate the nation's slave-owning, settler colonialist history. Still, others attempt to make any attempt at such an investigation illegal or mandate that students learn a whitewashed and wildly inaccurate version of American history (via NBC News). Like the late-Victorian era empire that birthed Stoker's "Dracula," the U.S. (and the world at large) finds itself at a turning point. Society is as riddled as ever with fears that the Other — any marginalized person — is responsible for the nation's "cultural decline."

Every age gets the monster it deserves ... or is

In an interview with Tufts Now, Erika Lee — author of "America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States" — described her subject as "a shapeshifting, wily thing, just like racism. You think it's gone away, and it comes back. It evolves..." Dracula is xenophobia incarnate: He's an immortal and evolving shapeshifter.

But if this kind of fear-bred hate is ignorant and irrational, why watch a movie that makes those terrors tangible and visually repulsive? If something's not going away — if it's going to continue to haunt humanity, halt progress, and incite violence — we need to recognize it, not just in stories and others, but in ourselves. That recognition is, and always has been, what horror does best.

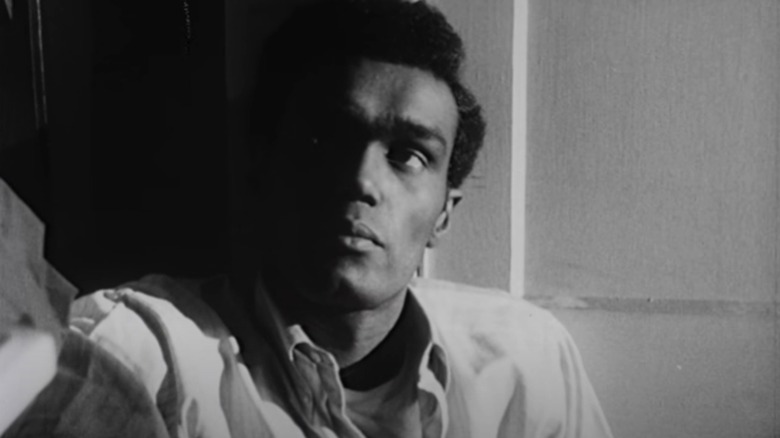

All horror is at once a product of, and reflection on, the time and place in which it was made. What any given monster represents may remain more or less stagnant, but how that representation speaks to the viewer is forever evolving. Zombies, for instance, are always a messy combination of our fear of a loss of autonomy, and, like Dracula, our uneasy relationship with the finality of mortality. However, how that loss of autonomy manifests and reflects society's fears has changed over time. George A. Romero's "Night of the Living Dead" ghouls touched on white America's anxiety over the Civil Rights movement, while "Dawn of the Dead" spoke to capitalism run amok, and the infected of "The Last of Us" hit on current anxieties over climate change.

Right now, we don't deserve sexy Dracula

Each time we revisit these monsters, we learn a little more about what it means to inhabit and navigate a given time and place. When that time and place is in crisis (as the past few decades most certainly have been), education becomes all the more vital to our growth as a species. As horror novelist Stephen Graham Jones told the NYT, "Horror doesn't just reflect our fears and anxieties back at us. It also helps us process them ... Even amid the jump scares and houses that are obviously haunted, horror can get you thinking, can get you talking. That's the key to what horror can do. Horror can shine a light on things we'd rather ignore, can confront us with our failings. Horror can challenge us to do better."

Sexy, funny, silly, badass, or melodramatic tween Dracula can do, and has done, a lot for us. At times, his gender-bending ways have challenged us to embrace more open views on sexuality and the gender spectrum. But what any one of those Draculas can't do is help us see, process, think, and talk about our capacity to be truly repulsive, beastly, predatory, and murderous to other human beings. "No matter how much you see of [Javier Botet's Dracula]," wrote the AV Club's Matthew Jackson, "You keep wanting a closer look." And the desire to take that long, hard look at our most hideously-motivated anxieties is something we could use more of in cinema.

By resurrecting Stoker's use of Dracula as the dreadful Other coming to infect, prey upon, and transform decent British folk into a monster like himself — and by making that Dracula dreadful, and using Aisling Franciosi's Anna (a woman and stowaway) as the one canary in the coal mine — Øvredal's film reminds us that the scariest evil isn't necessarily the one we can't see. The scariest evil is the one we willfully refuse to witness even when it's in the same small boat as us, hiding in plain sight, and chipping away at our humanity.