Small Details That Explain Confusing Movie Endings

If you're watching a movie for the first time, chances are you aren't paying attention to every single detail. Spotting specific film techniques or bits of foreshadowing usually doesn't happen until later viewings — unless you're the type of person that always knew who the murderer is in Agatha Christie novels. Still, for the average person, there are some films that seem to elude easy interpretations even with multiple rewatches. These are movies that traffic more in dream logic or false identities than in M. Night Shyamalan-esque showstopping twists.

Some movies are made murky in the editing process. Others are exactly as abstract as originally intended. Luckily, many of them include elements of symbolism or foreshadowing that make their ambiguous endings just a little bit more clear. If you've ever wondered who exactly the Thing is in The Thing or whether the driver dies in Drive, this list is for you. From unwinnable chess games to misleading references, here are small details that help explain confusing movie endings. Naturally, we'll be spoiling all the movies on this list. Consider yourself warned.

The Thing checkmates MacReady

The ending to John Carpenter's The Thing has stymied fans for decades. After two hours of paranoia and mistrust, MacReady (Kurt Russell) and Childs (Keith David) are sitting outside the burning wreckage of the research station waiting to freeze to death. Neither can be sure that the other isn't actually a Thing in disguise, and we know the Thing can survive being frozen, so all it has to do is wait. MacReady is the one who suggests waiting, but Childs is the one who ran off into the blizzard for seemingly no reason. Which of them is the Thing?

In the opening scene, MacReady is playing chess against a computer. Right when he thinks that he's won, he's shocked by a surprise checkmate, and pours whiskey into the machine in revenge. This sets the stage for the film: as with a game of chess, the Thing takes all the pieces off the board, eventually maneuvering MacReady into a checkmate. The Thing could be Childs, since MacReady toasts to him in the same way he "toasts" the computer, but ultimately it doesn't matter, since the Thing has already won by killing or infecting everyone who knows about it. When spring comes and the research station is investigated, the Thing can hitch a ride back to humanity and end the world. It's no wonder that Carpenter considers the film one third of his "Apocalypse Trilogy," since it sure seems like checkmate for the human race.

Total Recall is a dream

If there's any science-fiction film whose meaning you'll probably end up debating at 3 a.m. with a friend, it's 1990's Total Recall. Director Paul Verhoeven crafted a genuine sci-fi masterpiece by mashing up the original Philip K. Dick short story "We Can Dream It For You Wholesale" with the raw physicality of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his prime. The central question of Total Recall revolves around whether Douglas Quaid (Schwarzenegger) is dreaming the events of the film or if he really did wake up during the Recall procedure to find that he was an undercover secret agent.

There are arguments to be made for both interpretations, but if you pay attention to the scene where the Recall doctors are explaining the procedure to Quaid, you'll notice that they go over nearly every single major plot point of the film. Most significantly, there's a moment where the television in the Recall office shows the Martian mines, the setting of the final action sequence. There are plenty more details that hint that the entire movie is in Quaid's head, but for what it's worth, that's the interpretation that Verhoeven himself agrees with on the DVD commentary.

The cult makes an early appearance in Hereditary

Easily one of the scariest horror movies released in the last few years, Hereditary grapples with some big questions. What does it mean to live with guilt after you do something you can never take back? Do children always inherit their parents' trauma? And most importantly, who are the cultists at the end of the film? Well, you might have been too busy getting terrified by the final 20 minutes to realize it, but those naked cultists were actually present in the very first scene. Annie (Toni Collette) is surprised by the turnout for her mother's funeral, and wonders how her mother knew so many people when she never seemed to have any friends. As it turns out, worshiping a demon is a great way to meet people.

As for the cultists' plan, that's likewise set up early in the movie. When Annie attends a group meeting for dealing with grief, she mentions that her brother, who committed suicide years earlier, was scared of their mother. According to Annie, he was worried that their mother was trying to "put people inside him." It sounds like the ravings of a schizophrenic, but as it turns out, that's exactly what their mother was trying to do. She was looking for a male host for the demon Paimon as part of the cult's evil plan.

You could probably watch Arrival out of order

Like most Denis Villeneuve movies, there's a lot of complicated stuff happening in Arrival. In the film, strange aliens land all over the globe and it's up to linguistics expert Louise (Amy Adams) to keep humanity from bombing the peaceful visitors out of existence. The ultimate twist of the movie is that what audiences thought was a flashback to the death of Louise's young daughter early in the film was actually a flash-forward. The aliens' language allows for the ability to see time non-linearly, showing Louise that her daughter will die years before she's ever even conceived.

The film plays completely fair with this twist, though. The aliens' written language is drawn through circular glyphs that appear in the air — an early clue that they're not writing sentences the way humans bound to linear time would. An early conversation between Louise and Ian (Jeremy Renner) further illuminates the twist when they talk about the power that language has to rewrite your brain patterns. Even the aliens' nicknames play into the broader themes of miscommunication: they're called Abbott and Costello, referencing two legendary comedians who continually misunderstood each other in their comedy bits.

Annihilation is about wanting to get annihilated

Annihilation is one of the more purposefully confusing entries in this list. The film continually encourages you to doubt what you're seeing and wonder what's actually "real." As the explorers investigate the Shimmer, there's multiple times where the audience is given information that turns out to be false or half-true. The most confusing moment is when Natalie Portman's Lena battles her half-formed doppelganger in a wordless dance. When the sequence ends, it's impossible to be sure that the Lena we see walk out of the Shimmer is the same one we've been following. To make things even more chilling, when she reunites with her husband Kane (Oscar Isaac), who the audience has realized is actually a doppelganger, the couples' eyes change to match the Shimmer. Are they human or are they (alien) dancer?

Well, the short answer is that it doesn't really matter if they are who they seem to be. Both their original versions and their doubles are mutually bound by vice. When Lena "fights" her double in the lighthouse, it's less of a fight and more of a continual struggle to get out of her own way, literally. Everyone who goes into the Shimmer does so with some form of self-destructive tendency, from addiction to infidelity. That Lena and Kane's eyes show signs of the Shimmer just show that it's not the Shimmer that's inside them; it's their self-destructive natures. The Shimmer might be gone by the end of the film, but what it represented isn't.

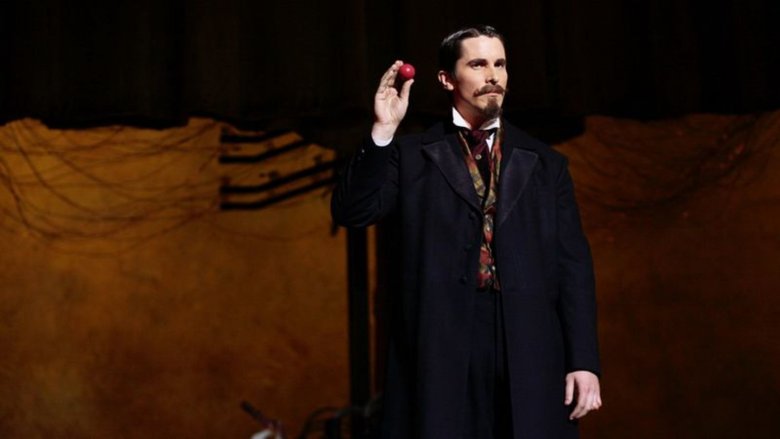

The Prestige shows its hand immediately

Director Christopher Nolan has earned a reputation for himself as someone who makes complex movies, and while that's not untrue from a technical standpoint, it's a bit overblown with regards to the plotting of his films. In fact, the most confusing interpretations of his work tend to focus on actively misreading or ignoring key points of dialogue in order to keep wondering about what's actually real (take, for instance, the long discourse about whether Hobbs is awake or dreaming in Inception). To be fair, that might be due to how much of a magic trick his films tend to be. Focus too long one scene and you'll miss another that makes everything clear.

In The Prestige, the ultimate twist is that Borden (Christian Bale) is actually twin brothers who have spent their entire lives in pursuit of the ultimate magic trick. In true Nolan fashion, he lays out the twist immediately, but the audience wasn't paying close enough attention. When Angier (Hugh Jackman) is reading Borden's stolen diary in an early scene, the narration says, "We were two young men at the start of a great career. Two young men devoted to an illusion. Two young men who never intended to hurt anyone." The audience is primed to believe that it's referring to Borden and Angier, but it's actually referring to the twins. The camera even pans over Borden sitting next to a bearded gentleman with a hat and fake nose that looks suspiciously like Christian Bale. Are you watching closely?

The Driver is the frog, not the scorpion

Despite getting sued for false advertising, Drive is a pretty great movie. It's got Ryan Gosling giving a powerful performance as an unnamed driver, fantastic cinematography, and one of the most earworm-esque scores you're likely to hear. All that side, the ending has baffled audiences since its release. When Gosling drives off at the end of the movie after being painfully stabbed, it's unclear whether he lives or dies.

The answer resides in a reference that Gosling makes late in the film when he asks a traitorous mob boss if he knows the parable of the Scorpion and the Frog. Since the Driver wears a Scorpion jacket, you'd expect it to be a subtle threat to the mob boss, letting him know that the Driver is going to kill him. In actuality, the Driver is the frog, compelled to help someone in need even though it means his own death. The meaning of the Frog and the Scorpion is that both creatures are acting according to their own natural drives, and both die as a result. The fact that the Driver wears a jacket with a Scorpion on the back means that he's fully aware that he'll be betrayed and eventually die, which is exactly what happens by the end of the movie.

Are we human or are we Replicant Blade Runners?

With over half a dozen distinct cuts of the film, it's totally understandable to be a little confused about the meaning of Blade Runner. The movie's production design and cinematography have rightly been lauded for years, but the multiple cuts of the film's plot has left audiences even more in the dark for a story that was always fairly opaque. The biggest question viewers tend to have (beyond just why the film is called Blade Runner at all) is whether Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is a replicant himself, rather than just a human conscripted to hunt renegade replicants. The Director's Cut is where you'll find the clearest evidence for Deckard being a replicant.

Throughout the film, Deckard has a recurring dream about a unicorn. Though he never tells anyone about the dream, Gaff (Edward James Olmos) leaves an origami unicorn in Deckard's home, implying that Gaff is fully aware of Deckard's dream. That all points to Deckard being a replicant himself, which might explain why Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) saves him in the final action sequence.

You're not my real mom!

1977's House is without a doubt one of the strangest films ever made. Directed by Nobuhiko Obayashi (with story input from his pre-teen daughter), the film is a fever dream of nightmarish imagery and unforgettable visuals. The ending is no different — after the rest of the girls have been killed off one by one, Ryoko, Gorgeous' new stop mother, arrives to visit the girls. She finds Gorgeous, presumably possessed by her evil aunt. The two shake hands as equals before Ryoko is burned away. What does it all mean?

In an early scene, Gorgeous is told by her father that he is finally remarrying after years of living as a widower, and Ryoko will be her new mother. Gorgeous responds with anger, scratching out photos of her father and despairing that anyone would ever try to replace her mother. When the girls go to the eponymous house, they're confronted with constant references, symbolic and otherwise, to femininity, marriage, and motherhood. Gorgeous is terrified of accepting Ryoko's place in her home because that means that the ambiguous role of caretaker that she holds towards her father will be erased. The ending, then, is her ideal scenario: a meeting between her and Ryoko not as a new wife and her soon-to-be-step-daughter, but as two equals. That it ends with Ryoko being burned away isn't a coincidence; Gorgeous wants to be both adult (a caretaker for her father) and a child (wishing death on anyone who intrudes on their happy house).