Why Shelley Duvall Almost Quit The Shining

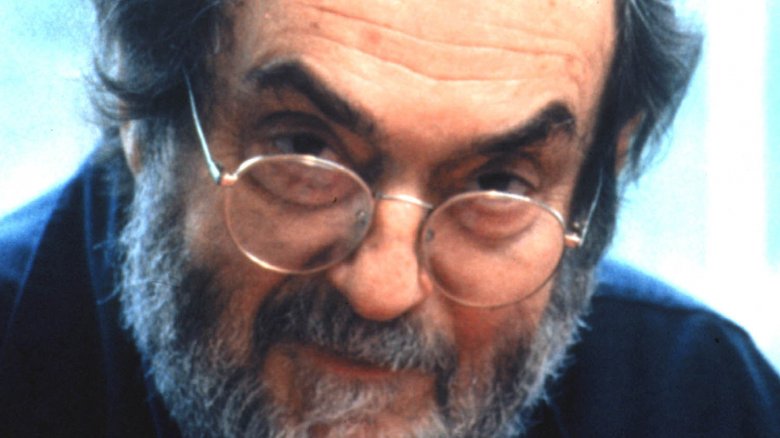

"Don't sympathize with Shelley," Stanley Kubrick mutters before turning his attention back to the scene he's preparing to shoot. He seems to be at least half-joking, maybe attempting a good-natured ribbing of his sometimes snarky star. This is, after all, the darkly comedic personality responsible for the apocalyptic slapstick of Dr. Strangelove. But as the crew of The Shining bustles around Shelley Duvall and her protests, no one seems to be laughing.

This is a scene from a short documentary titled Making The Shining, shot on the set of the horror classic by Kubrick's then-teenaged daughter Vivian. It remains one of the most fascinating behind-the-scenes looks at a film production, in part because the documentary's subjects are much more at ease around the director's kid than they would be for a studio-sanctioned camera crew. Vivian had a skilled eye even then, and she captured an intimate slice of the day-to-day life on the set of a masterpiece.

But between the methodical efforts of Stanley Kubrick and the ribald antics of Jack Nicholson, the documentary keeps coming back to Duvall. Her role in the movie called for her to channel near-constant terror, and clearly not all of that anxiety stopped when the cameras did. What made her experience so miserable? Let's take a look at the many reasons Shelley Duvall almost quit The Shining.

An illustrious past

Shelley Duvall made her screen debut in 1970 with a role in Brewster McCloud, an offbeat comedy from legendary director Robert Altman. She landed the part of Astrodome usher Suzanne quite by accident after a chance meeting with Altman, who insisted Duvall would be perfect, despite the fact that she was an inexperienced college student studying nutrition. "I got tired of arguing, and thought maybe I am an actress," she would later recall.

It was the beginning of a long collaboration, as Altman cast Duvall five more times before the end of that decade. She garnered particular attention for her lead role in Altman's 1977 drama 3 Women. Duvall rounded out the '70s with an appearance in Annie Hall, a star turn in a TV adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's "Bernice Bobs Her Hair," and a guest hosting gig on Saturday Night Live. Having explored these diverse avenues of comedy, drama, and period pieces, Shelley Duvall would mark the start of the 1980s with an entirely new challenge: horror.

A new writing project

It might seem strange to think now, but there was rarely any guarantee that Stanley Kubrick's films would be critically or commercially successful. After coming of age as a photographer, Kubrick began his movie career with critically lauded but little-seen dramas like The Killing and Paths of Glory. His first major Hollywood attention came in 1960 with the release of Spartacus, a grand epic that he directed by special request of its producer and star, Kirk Douglas. But even with this success came a reputation for conflict, as Douglas was outspoken about the difficulties of working with the young perfectionist.

Kubrick followed Spartacus with a string of films that would eventually rank among the most important and influential works of all time. However, very little of that respect was waiting for them upon their original release. Lolita was plagued by the scandalous reputation of its source material. Dr. Strangelove polarized audiences with its bleak comedy (a "shattering sick joke," the New York Times called it). People didn't quite know what to make of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The leisurely-paced Barry Lyndon bored American crowds. And then there was A Clockwork Orange, a film so controversial for its violence and sexuality that Kubrick himself had it pulled from theaters.

As a new decade dawned, the next Stanley Kubrick project may have been an intriguing artistic prospect for an actor, but it would hardly be an easy ticket to stardom.

A demanding job

As it turned out, the next Stanley Kubrick project was The Shining, an adaptation of Stephen King's bestselling novel. Though the director had dabbled in upsetting and unsettling material, this would be a much more direct turn into the realm of horror. King's book uses a haunted hotel as the setting for the dissolution of a family and a man's descent into alcoholism. Kubrick, along with co-screenwriter Diane Johnson, would twist The Shining into a labyrinth of madness and metaphor, exploring masculinity, white privilege, and systemic evil.

The core of the story would remain the domestic drama of the Torrance family, their already tense dynamic heightened by the isolation of the Overlook Hotel. Wendy Torrance was never going to be an easy role for any actor to play. As the wife of alcoholic writer Jack and mother of troubled psychic Danny, Wendy's plight echoes that of so many real women trapped in abusive marriages. Add to this the fact that Wendy is the least attuned to the story's supernatural goings-on, and you've got a part as thankless as it is challenging. Shelley Duvall accepted the job of playing Wendy to Jack Nicholson's Jack, and it would become a turning point in her career.

A tremendous sense of isolation

The scale of a movie's production usually dictates the cast's experience. A low-budget, character-driven drama can serve as an intimate bonding experience for a small ensemble. A larger shoot allows a troupe to form a kind of support network to keep up morale through the arduous process of epic moviemaking. The making of The Shining, however, was an uncomfortable mix of these two extremes.

Members of the Overlook Hotel's mortal staff deliver some necessary exposition in the opening scenes, and a cadre of spirits hover over Jack's gradual loss of sanity. However, the bulk of The Shining's scenes focus squarely on the three Torrances as the family slowly unravels. Clocking in at nearly two and a half hours, though, the movie reaches a scope far beyond that of just about any other film with so small a cast. With six-year-old Danny Lloyd in the role of Danny Torrance (Kubrick worked hard to shelter the child from the movie's more horrific elements), Shelley Duvall and Jack Nicholson rarely had any coworkers but each other to turn to for the entirety of the shoot.

Moments of déjà vu

And what an arduous shoot it was. Most movies spend a matter of weeks in principal photography, with even complex blockbusters shooting for maybe half a year. The Shining, however, kept Duvall and Nicholson in front of cameras for 13 months. Several factors contributed to this sprawling schedule, but it largely all came down to the director's relentless perfectionism.

Stanley Kubrick was rather infamous for demanding take after take of many scenes. Joe Turkel, who portrayed ghostly bartender Lloyd, would later explain, "Stanley was looking for the shot, the perfect shot, and there's no such thing." Turkel recalled rehearsing a conversation with Nicholson for six weeks. If Kubrick required that much preparation for so simple a scene, it's easy to imagine how the film's graceful Steadicam sequences and complex practical effects bloated the schedule to such extremes. Shelley Duvall, in particular, bore the brunt of this perfectionism, performing an emotionally charged confrontation scene a record-breaking 127 times.

Burn it down

Stephen King's novel comes to a fiery climax in which Jack Torrance's murderous rage causes him to neglect his furnace-resetting duties, leading to an explosion that consumes the Overlook. Stanley Kubrick and Diane Johnson jettisoned this ending in favor of a more subdued conclusion in which Jack freezes to death while Wendy and Danny flee, leaving the hotel to lie in wait for the next season's visitors. The only remnant of the "unstable boiler" in the movie is a scene in which Wendy tends to the gauges, illustrating that Jack was never really doing his job anyway.

While the film itself lacked this cleansing inferno, life imitated art for the cast and crew of The Shining. Just as production finally seemed to be nearing its end, a fire destroyed one of the central hotel sets. Though the exact cause was never determined, it seems possible that the massive wattage required to simulate the harsh, cold winter light blotting out the view through the Overlook's windows may have had something to do with it. At any rate, the incident added $2.5 million and three extra weeks to the production, further exhausting an already harried cast and crew.

I've always been here

"From May until October, I was really in and out of ill health," Shelley Duvall reveals to Vivian Kubrick in Making The Shining. As she recounts the taxing experience of being uprooted from home for so long (The Shining was shot entirely in England), the documentary cuts to on-set footage of Duvall lying on the floor while production assistants rush to bring her blankets and water. Reflecting on this scene in 2011, Duvall remembered it as "a really bad anxiety attack" brought on by the long days with rare breaks. "We were shooting long days, sometimes 15-16 hours," she said, "and it really does take a lot out of you."

As those long days turned into long weeks and long months, it's easy to see how Duvall and the rest of The Shining's cast and crew may have felt like their stay at the Overlook would never end. To make matters worse, the script was constantly shapeshifting as they shot it, as another scene in the documentary reveals. During a visit to the set, Stanley Kubrick's mother is astonished by Jack Nicholson's revelation that he and Duvall receive freshly rewritten pages each day, with a system of color coding to keep the myriad versions straight. "Aren't you exaggerating a little bit?" she asks, to which Nicholson and Kubrick replay in amused unison, "No!"

Responsibilities to my employers

While Kubrick can be seen in Making The Shining sharing leisurely chats with Nicholson, he seems to have extended very little of that amity to Shelley Duvall. Nicholson noticed this double standard, describing Kubrick as "a different director" when working with his co-star. It makes sense for their characters — Jack has to become gradually empowered with unearned confidence while Wendy grows increasingly terrified.

But that kind of method directing hardly seems to justify the coldness on display in the documentary. Just look at Kubrick's skeptical eye-rolling while Duvall shows him the way her hair is falling out from the stress of the role. Heated words are hardly a rarity on a tense film set, but even Kubrick's own daughter couldn't help but highlight his constant criticism of Duvall's work.

Duvall's feelings about the experience would remain complicated. Though she never shied away from discussing her strenuous relationship with the director, she also claimed to be grateful for the experience. "Even though the atmosphere on set was sometimes unpleasant, I'm now remembered for a film that's become a horror classic," she reflected in 2011. "The fact that people are still watching and talking about it 31 years later amazes me."

Looking for a change

When The Shining at last hit theaters in May of 1980, it did little to shift the streak of cultural confusion over Kubrick's films. Greeted by mixed reviews, lukewarm box office, and derision from the author of its source material, it was more or less shrugged off by audiences at large. Its reappraisal as a masterpiece would take years.

Shelley Duvall, meanwhile, sought out more comforting work experiences as soon as her stay at the Overlook was finally over. She returned to the familiar realm of working with director Robert Altman, who cast her alongside Robin Williams in a lighthearted musical version of Popeye that same year. Afterward, much of her career would be defined by work for children. She produced and starred in multiple kids' shows for the Showtime network, including Faerie Tale Theatre, Tall Tales & Legends, and Shelley Duvall's Bedtime Stories. She even tried her hand at music with an album of lullabies and another of Christmas songs.

Epilogue

Shelley Duvall retreated from the public eye as the new millennium began, making her final screen performance to date in the independent comedy Manna From Heaven in 2002. Apart from the occasional interview about her career, she kept to herself in her rural Texas home for several years after. In 2016, she resurfaced with an appearance on Dr. Phil, revealing her struggles with mental illness. "I'm very sick," she pleaded. "I need help."

The interview, in which Duvall went on bizarre tangents and seemed frequently disoriented, immediately drew harsh criticism. Viewers on social media accused Phil McGraw of exploiting Duvall's plight for shock and entertainment. One of the most vocal protests came from Vivian Kubrick, who tweeted an open letter to Dr. Phil, expressing "complete disgust" at McGraw's "utterly heartless form of entertainment, because it has nothing to do with compassionate healing."

But this debacle was not without a silver lining. The Actors Fund, a charitable organization dedicated to assisting entertainers in need, reacted quickly with an offer of aid. "We often reach out to people when we hear in the press that they've fallen on hard times," Actors Fund director Keith McNutt stated, "and we'd be happy to help her in any way that we can." Shelley Duvall may be facing even greater challenges than she did on the set of The Shining, but a happy ending hopefully lies ahead.