The Untold Truth Of Watchmen

First published in single issues by DC Comics between 1986 and 1987, Watchmen changed superhero comics — and it continues to do so. In 2017, over 30 years after the release of the original series' first issue, DC Comics brought the characters of Watchmen into DC's prime universe in the 12-issue maxi-series Doomsday Clock, allowing characters like Ozymandias and Doctor Manhattan to interact with DC regulars like Batman, Superman, and the Joker.

More impressive is Watchmen's reach outside of comics. It's been adapted to film, video games, and a Watchmen-inspired television series at HBO. Its critical acclaim reaches far beyond comic book fandom. For example, Watchmen is the only graphic novel to find a home on Time's "All-Time 100 Novels" list; sharing space with such classics as The Great Gatsby, 1984, and To Kill a Mockingbird.

Like most work that has reached similar levels of popularity, Watchmen's audience suffers its share of misinformation. Much of what is assumed about Watchmen and its making would be loudly shouted down by creators Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. The inspirations for Watchmen, its creators' intentions, and the contributions each creator brought to the table are often misunderstood or overlooked. And just as each re-reading of the story can make you see something you never noticed before, there's plenty that went into the comics' making that most fans don't know. Here's the untold truth of Watchmen.

The untold truth of Dave Gibbons

It's a strange irony that in a medium as concerned with images as comic books, the writers tend to get most of the attention. Watchmen is no exception. As the comic's artist Dave Gibbons said when he spoke to Wired in 2008, "People unacquainted with graphic novels, including journalists, tend to think of Watchmen as a book by Alan Moore that happens to have some illustrations. And that does a disservice to the entire form."

Much of the imagery surrounding Watchmen was not only drawn by Gibbons, but designed and conceived by the artist. While being interviewed by Neil Gaiman in 1987, Gibbons said it was his idea for the cover of Watchmen #1 to be of the now iconic blood-smeared smiley face. It was Gibbons, with Moore's input, who designed the physical appearance of the characters. And perhaps most significantly, it was Gibbons who constructed Watchmen's world. Moore and Gibbons wanted to get across the idea that the world would have changed in significant ways because of the presence of superheroes, and Gibbons came up with many of the details.

For example, it was Gibbons' idea that fast food restaurants would be replaced by Asian restaurants, because overseas wars would effect a massive migration of refugees from Asia to the U.S. The cars you see in the background of Watchmen are mostly electric — and the streets are littered with hydrant-liker chargers for them — because Dr. Manhattan's godlike powers included creating the kind of rare materials needed to make those electric cars work.

The Mighty Crusaders

Most fans incorrectly believe that Alan Moore's first plan for Watchmen was meant for the heroes of Charlton Comics. Charlton's superhero properties were acquired by DC Comics in 1983 and Moore first pitched Watchmen to DC editor (and former Charlton editor) Dick Giordiano as including Charlton characters. According to Moore, Giordiano liked the story, but not the cast. Giordiano wanted DC to be able to go in different directions with their new properties. Instead, Moore created characters based on the Charlton crew. Charlton's Blue Beetle became Nite Owl, Captain Atom became Doctor Manhattan, The Question became Rorschach, et cetera.

However, in 2000's Comic Book Artist #9, Moore talked about how the initial Watchmen concept had nothing to do with DC or Charlton characters, but with Archie Comics characters. Though not Archie himself. Or even Jughead.

It was Archie's dormant super-team, the Mighty Crusaders, that Moore first envisioned when putting together the story that would become Watchmen, though his original idea was more expansive. Moore said it started with him thinking, "Wouldn't it be nice if I had an entire line, a universe, a continuity, a world full of super-heroes... whom I could then just treat in a different way?" With their sporadic appearances through the decades, the Mighty Crusaders occurred as natural candidates to Moore. Instead of the Comedian, it would be Archie's character the Shield whose murder would open the story. Alas, it wasn't meant to be, and perhaps it's for the best. If Moore and Gibbons had used the Crusaders, more contemporary opuses would remain unrealized.

Precursors to Watchmen

Watchmen wasn't Alan Moore's first attempt at telling a different kind of superhero story. In the early '80s, he wrote Marvelman (later retitled Miracleman) about a superhero introduced in the '50s. Marvelman took the hero to much darker places than he was used to. Speaking to Comic Book Artist, Moore said that while DC Comics was impressed with Marvelman, he suspected it was why they kept him away from their marquee heroes, "for fear [they] might end up like Marvelman, with strong language and childbirth all over the place."

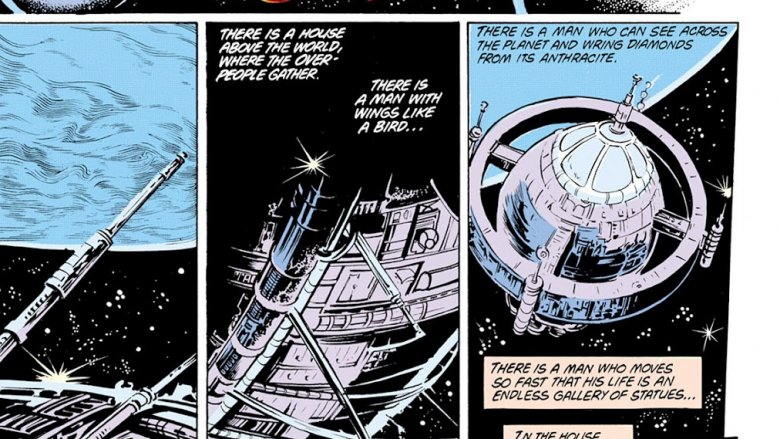

Another example was, ironically, not a superhero title. Moore took over DC's horror title Swamp Thing — a horror comic whose story existed in the prime DC universe. Moore handled this by including the Justice League in a story while treating the heroes almost like dark, unseen gods. He opened Swamp Thing #24 with, "There is a house above the world, where the over-people gather. There is a man with wings like a bird... there is a man who moves so fast that his life is an endless gallery of statues."

While Moore told Comic Book Artist his work on Marvelman was more of a precursor to Watchmen than Swamp Thing, in 2002 he told Engine Comics that the horror comic did help him build one tool he needed for Watchmen. He compared trying to figure out the thoughts and concerns of the "mass vegetable consciousness" of Swamp Thing to the challenge of stepping into the shoes of Watchmen's Dr. Manhattan, a character with godlike powers who exists simultaneously in multiple points of time and space.

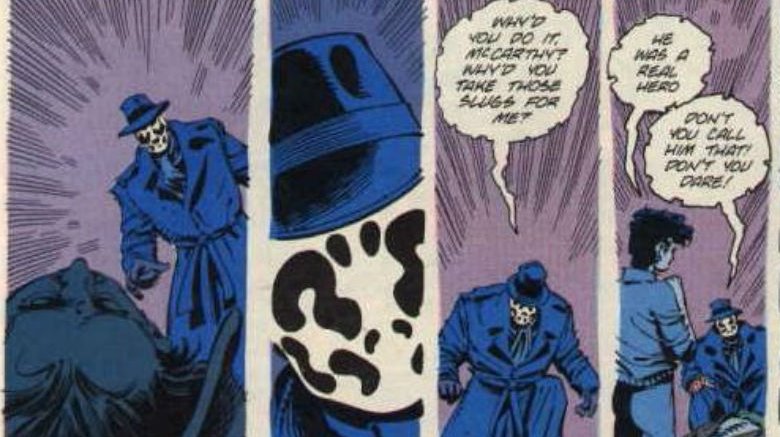

Ditko vs. Moore

Steve Ditko and Alan Moore are not two men you would ever have expected to find at the same dinner parties. The late Ditko was an unapologetic believer in Objectivism, the philosophy developed by Ayn Rand that's often associated with right-wing politics and has inspired numerous contemporary politicians on the right. Moore, on the other hand, described himself as a left-leaning anarchist in 2000's Comic Book Artist #9. Regardless, Moore has expressed a lot of admiration toward the late Ditko. As a result, though he had nothing to do with its creation, Ditko is responsible for more than one might think about what makes Watchmen so memorable.

Rorschach was based on a superhero created by Ditko: Charlton Comics' the Question. Ditko would later create the hero Mr. A in the fanzine witzend #3, who was a more blatant champion of Ditko's objectivist views. Moore's Rorschach was something of a fusion of these two heroes — with his faceless look and clothes resembling the Question's, and his black-and-white moral compass mirroring that of Mr. A.

Considering this, there is an interesting detail about Rorschach that is never explicitly stated in Watchmen, but seems obvious: Rorschach — the man who defines good men as those "who believed in a day's work for a day's pay" — was on welfare. He has his own apartment but he doesn't have a job. His black-and-white moral code wouldn't allow for him to steal — even from the criminals — so public assistance is the only way he could have survived. You can only swipe beans from Nite Owl's kitchen so many times.

They aren't fascists

Watchmen was one of a number of superhero comic book series published in the mid-'80s that are often associated with one another because they're said to explore the notion of superheroes as fascist figures. Examples include Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Marvel's Squadron Supreme, in which superheroes with good intentions nevertheless turn the U.S. into a totalitarian state. With brutal scenes in Watchmen of the Comedian and Dr. Manhattan killing Vietnamese soldiers and civilians, Rorschach torturing victims for information, or the Minutemen using their abilities and technology to break up protests, it's easy to see why readers make the association with fascism. But in a 1987 interview, Alan Moore said his Watchmen characters weren't fascists.

"Rorschach's not a fascist; he's a nutcase," Moore said. "The Comedian's not a fascist; he's a psychopath. Dr. Manhattan's not a fascist; he's a space cadet. They're not fascists. They're not in control of their world."

Arguably, Moore's stated intentions were much more damning toward superheroes than any series before or since. Moore said he and Gibbons weren't trying to reveal a fascist leaning in superheroes, but rather "to show how superheroes could deform the world just by being there, not that they'd have to take it over, just their presence there would make the difference." As an example, he compared the origin story of Dr. Manhattan to the invention of the atomic bomb. "[T]he atom bomb doesn't take over the world," Moore said, "but by being there it changes everything."

Fearful Symmetry

When talking about what is unique about Watchmen, the darker subject matter and the violence are the focus for most. What's too often forgotten are the visual innovations it brought to comic books. For example, there were the covers. There were no fight scenes and no heroes posing. The covers included a Rorschach drawing, a torn black-and-white photo, and a spinning perfume bottle. Each cover was part of the first panel of each issue. In a 1987 interview, Dave Gibbons said, "The cover of the Watchmen is in the real world and looks quite real, but it's starting to turn into a comic book, a portal to another dimension."

A perfect example of Watchmen's visual cutting edge was its fifth issue, titled "Fearful Symmetry." Each page and panel of Watchmen #5 was designed to act as a mirror to its opposite. For example, the first panel of the first page centers on the reflection of a skull-and-crossbones sign in a sidewalk puddle. The last panel of the last page features the same reflection. The second panel on the first page focuses on Rorschach's foot about to step in a puddle. On its opposite, Rorschach's feet are dragged through a puddle. Likewise, the scenes of each page mirror their opposites. In the center panel of page 10, Dan Dreiberg looks longingly at Julie, who is gazing out a window. In the center panel of page 19, Dreiberg looks at Julie from behind while Julie sits in front of a mirror. It continues to the very middle of the comic, pages 14 and 15, featuring the supposed assassination attempt (we later learn it was staged) on Ozymandias.

Saturday Morning Watchmen

The day before the release of Zack Snyder's film adaptation of Watchmen, British animator Harry Partridge gave the world a very different "interpretation" of the classic graphic novel.

Jokingly claiming he had ripped it from an old VHS tape, Partridge posted Saturday Morning Watchmen. Styled like an animated intro from an '80s cartoon, the video features such memorable bits as Rorschach lovingly petting the same pair of dogs he slaughtered in the comic, Ozymandias saving the Comedian from the fatal fall that opens Watchmen, and the whole gang enjoying a lighthearted pizza party. Ozymandias' exotic feline Bubastis isn't forgotten — he's actually the first to speak in the intro, sounding a lot like Snarf from the '80s Thundercats cartoon. It's worth a watch, if for no other reason than the catchy theme song that happily tells you about all the different quirks and powers. Schooling you on Doctor Manhattan, the song proclaims, "Jon can give you cancer/And he'll turn into a car!"

The only downside is that after watching the intro, you really want to watch a full episode. Considering the live-action film's approval rating among critics, a lot of people might have preferred Partridge's version over Snyder's.

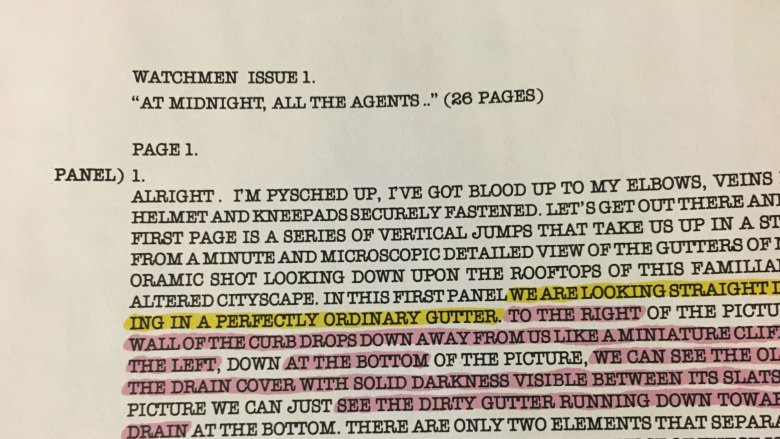

The scripts

In the introduction to Watchmen: The Annotated Edition, editor Leslie S. Klinger writes that Alan Moore's scriptwriting was already legendary in the comics industry by the time work on Watchmen began. Klinger quotes artist Stephen Bissette — who worked extensively with Moore on Saga of the Swamp Thing — who said Moore's scripts were "long, narrative letters." Klinger points out that the 12 issues of Watchmen amounts to 340 pages of comics, while Moore's script for Watchmen was over three times as long: 1,042 pages.

Looking at the excerpt of the script for Watchmen #1 printed in 2005's Absolute Watchmen, it's easy to see how Moore produced so many pages. His description of the comic's very first panel — which shows blood running into a gutter and The Comedian's iconic smiley face button — takes up the entire first page of the script. He writes conversationally, starting the description with "I'm psyched up. I've got blood up to my elbows, veins in my teeth and my helmet and kneepads securely fastened. Let's get out there and make some trouble!" Moore goes into more detail than you could ever imagine anyone needing to describe blood running into a gutter, including spending quite a bit of time worrying about whether artist Dave Gibbons should include a discarded candy wrapper in the panel. Ultimately, Moore gives Gibbons the final word on the wrapper, but not until he outlines exactly what Gibbons needs to consider when deciding.

The Question of Rorschach

It isn't a secret that the psychotic Rorschach was based on the former Charlton Comics hero known as the Question. But what you may not know is that Rorschach and his predecessor had a chance to meet one another. Kind of.

In The Question #17, Vic Sage (a.k.a. The Question) finds himself leaning toward more brutal tactics, lamenting the opportunities he's given his enemies because he supposedly hasn't dealt with them harshly enough. While in pursuit of a fugitive, Sage takes a plane to Seattle and picks up a copy of Watchmen at the terminal newsstand to read on the flight. He doesn't like Rorschach's bigotry, but he's impressed with his more violent skills. He falls asleep on the flight and dreams of the death of a private eye he knew — except in the dream, Sage is Rorschach instead of the Question.

When he lands and starts working on his case, he finds himself asking, "What would Rorschach do?" When a crook takes him out with a gun-butt to the head, Sage utters Rorschach's signature "Hurm." Toward the end of the comic, he regrets trying to emulate the more ultraviolent hero. When he's cornered by the crooks and they ask if he has any last words, Sage responds, "Yeah. Rorschach sucks."

HBO's Watchmen follows the graphic novel, not the movie

HBO's Watchmen debuted to rave reviews, and pretty quickly, a couple of things became clear about the show. First, the events of the series take place decades after the events of the original story. Second, and more importantly, HBO's Watchmen is a continuation of the comic book story rather than the movie. A brief, memorable scene in the first episode confirms it. As Angela (Regina King) drives her son home from school, Tulsa is pelted with a heavy torrent of tiny squid-like creatures.

In the Watchmen graphic novel, we learn Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias, is behind a conspiracy to violently bring about a utopia. Veidt recruits the world's best scientists to create a fake alien behemoth that Veidt transports to New York City — the hope being that the world's powers will stop fighting each other and unite to face this new "threat." In the 2009 film, this was changed so that Veidt manufactures an attack that appears to be from Doctor Manhattan, with the same results.

Since we know the "alien" squids aren't in the film, HBO's Watchmen can only be a continuation of the graphic novel. It could be these squid storms will be what uncovers Veidt's conspiracy, and we're already seeing hints of that. In Watchmen's second episode, a news vendor is spouting conspiracies to a man delivering newspapers, calling the raining squids a "false flag" to distract Americans.

The Tulsa massacre

One of the things Watchmen is known for is its alternate history. In the graphic novel, Richard Nixon is serving his fourth term as president, and the civil rights battles won in the '60s and '70s never happened because the superheroes were there to put down the protests. So when the first episode of Watchmen opens with a 1921 race massacre on the streets of Tulsa, you might think this is more fictional world-building, but it isn't. The Tulsa race massacre happened in the real world, and if anything, Watchmen only shows the tip of the iceberg.

As the L.A. Times recounts, the 1921 Tulsa massacre has been largely lost from our history books because of systematic attempts to cover up the events. As the paper explains, "Stories were removed from newspaper archives, and some official accounts were destroyed." This is likely part of the reason why the official death count of the massacre is 36, but "more recent estimates" put the number closer to 300 killed, along with around 800 injured.

According to the Times story, the massacre began after news circulated that a black man had assaulted a young white woman in an elevator, though later reports suggested he may have tripped and fallen onto the woman on accident. The white rioters, supported by the Ku Klux Klan, not only killed and injured black citizens, but they destroyed the black-owned businesses of Tulsa, places so successful that Booker T. Washington had coined the community as the "Black Wall Street of America."

In HBO's Watchmen, the capes have changed sides

If you're familiar with the graphic novel, the movie, or both, then one of the biggest differences you notice right away is that in HBO's Watchmen, the masked men and women are working with the cops.

In the original story, the Keene Act makes masked vigilantes illegal except for those working for the government. The only heroes we see employed by the feds are the Comedian, Doctor Manhattan, and Silk Spectre. The rest of the heroes are either officially retired or, like Rorschach, renegades who the police would love to get their hands on. So it's something of a shock when — with the exception of the Rorschach-inspired Kavalry — all of the masked people of HBO's Watchmen are police.

It seems likely this is a result of the White Night, an event that took place some years before the events of the series, where the Kavalry broke into the homes of most of the Tulsa PD and murdered the officers and their families as they slept. Most of the survivors immediately resigned, though Angela and Judd (Don Johnson) refused to back down. So presumably part of the reason for the masks is to protect the officers and their families. But certain officers apparently get special designation and rise above the yellow-masked rank and file. There's Angela, aka Sister Knight, Looking Glass (Tim Blake Nelson), the Red Scare (Andrew Howard), Pirate Jenny (Jessica Camacho), and Panda (Jacob Ming-Trent).

Return of the king

So far, only one character in HBO's Watchmen has appeared who was also in the graphic novel — Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias (Jeremy Irons). In the first episode, Veidt enjoys himself on a vast, idyllic castle property that he appears to share with two beloved servants. They serve him a cake with a single candle and gift him with an old pocket watch. He tells them he's written a play he wants the pair to star in called The Watchmaker's Son. This is a little strange already because you'd think in his waning years, the man who believes he saved the world would want to write about himself. But if you know Watchmen, then you know the Watchmaker's son can only be Doctor Manhattan.

Things get a lot weirder in the second episode. We learn who we thought were Veidt's only servants are part of a series of identical clones. Veidt watches a rehearsal of his play, which climaxes with the accident that turns Jon Osterman into Doctor Manhattan, including pyrotechnics that kill the actor playing him. No one seems particularly upset with this, and Veidt directs his clones to put the dead actor in the basement with "the others." What's not as dramatic but still noteworthy is that his servants bring him another cake, but this time with two candles. Assuming these events happen concurrent to what's going on in Tulsa, we know a year hasn't passed, which suggests the cake isn't a birthday cake after all, but something else.

Watching the watches

The image of the watch recurs over and over again in the Watchmen graphic novel. Each chapter ends with a ticking clock. The fourth chapter, "Watchmaker," goes back and forth in time through the lens of Doctor Manhattan's non-linear point of view, including stories of his watchmaker father. The symbol on Doctor Manhattan's forehead looks something like a watch face, as does the blood-splattered smiley face that's become so iconic in reference to Watchmen.

HBO's Watchmen continues this tradition, in images and sounds. There's, of course, the foreboding "tick tock" chant of the Rorschach-inspired Kavalry. When the Tulsa PD raids a Kavalry safehouse, we learn the group is using old lithium batteries from watches to build some kind of weapon. Of course, there's the pocket watch Adrian Veidt's servants give to him as a present, and there's also the name of his play, The Watchmaker's Son.

What does it all mean? Well, that could lead us down a bottomless rabbit hole of literary symbolism, but there are some obvious answers. On one hand, just as it was in the graphic novel, the watches serve as a countdown to something cataclysmic. This is also likely the reason why the candles on Adrian Veidt's cakes increase by one each episode (since it's clear a year hasn't passed between each episode). On the other hand, Watchmen has always been very concerned with time and how we perceive it, so the watches are a constant reminder of our strange relationship with time.

Visions of the past

HBO's Watchmen hasn't forgotten its roots, and the evidence is everywhere. There are plenty of callbacks to the graphic novel, including technological advances clearly inspired by the heroes of the source material.

For example, in the first episode, after some of the Kavalry members try to escape with their homemade bomb in a small plane, Judd and Pirate Jenny follow in a ship clearly modeled after the Nite Owl's airship, including its flamethrower which Nite Owl and Silk Spectre famously triggered during their love scene. In the second episode, we see someone in a winged get-up inspired by the Watchmen hero Mothman. He falls out of the sky while the police are investigating the crime scene where Judd was hanged, and the Red Scare beats the winged interloper for his trouble. Apparently in the world of Watchmen, Mothman technology is their version of drones.

We're also getting to see a "historical" show about the Minutemen unfold called American Hero. In the first episode, we only see ads for it, but we get an entire bloody, brutal scene involving Hooded Justice beating a group of robbers. The hero was only seen in flashbacks in the Watchmen graphic novel, and he's a perfect addition here. Considering his hood, the noose imagery, Judd's murder, and his secret KKK past, there's something disturbingly poignant about Hooded Justice in this narrative.