The Best Batman That Never Was

Since Tim Burton brought the Dark Knight to the big screen in 1989, Batman has appeared in 10 live-action feature films, and has been played by five different movie stars. He's had self-contained solo adventures, teamed up with Robin and Batgirl, joined the Justice League, battled the Joker three times, and made billions at the box office. For all of those big-screen adventures we saw and discussed, though, there are many more we didn't see.

Warner Bros. is always thinking about the next cinematic phase of the Bat, and they were particularly keen on searching for a new direction in the period between the release of the famously derided Batman & Robin in 1997 and the arrival of Batman Begins in 2005. There are numerous aborted Batman movie efforts from this period, but one still stands out as an extremely intriguing project that never got off the ground: Darren Aronofsky's adaptation of Batman: Year One. Here's why that developed-but-never-produced Caped Crusader adventure might just be the best Batman film we never got to see.

Ambitious beginnings

In 1999, Aronofsky was a young filmmaker fresh off the breakout success of Pi, his low-budget, black and white debut feature film about an obsessed mathematician. Pi is not exactly the kind of film you'd look at as a Batman director audition, but while Aronofsky was working on his follow-up, Requiem for a Dream, Warner Bros. was looking for new voices to revitalize the Dark Knight. Aronofsky met with executives and pitched them the idea of adapting a classic Frank Miller Batman story for the screen — except it wasn't Batman: Year One at first. Aronofsky's first idea was to adapt Miller's 1986 miniseries The Dark Knight Returns, the story of an aged Bruce Wayne who comes out of retirement to battle new threats in a gritty, futuristic version of Gotham City. As for how he'd go about making that film, Aronofsky came out of the gate with some big ideas, as explained in David Hughes' book Tales from Development Hell.

"I told them I'd cast Clint Eastwood as the Dark Knight, and shoot it in Tokyo, doubling for Gotham City," he recalled. "That got their attention."

As it turned out, Warner Bros. was more interested in going back to the beginning with Batman than exploring his later years. Eventually, so was Aronofsky, and his interests turned to Year One, Miller's other seminal Batman work.

A legendary collaborator

Batman: Year One isn't the only major Batman origin story out there, but it remains an essential piece of Dark Knight lore more than three decades after its publication, and ultimately proved to be a major inspiration for Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins. It's exactly the comic book property you want to adapt if you want to make a Batman origins movie, and Aronofsky was an energetic young filmmaker with a lot of big ideas. Warner Bros. had both of those things going for the project — and then they also got Frank Miller himself.

Miller, whose feature film work has since included collaborations with Robert Rodriguez on two Sin City installments and an adaptation of Will Eisner's The Spirit, was already in a good working relationship with Aronofsky. Sin City was a major visual influence on Pi, and the two had worked together on a potential adaptation of Miller's classic 1983 comic Ronin, so when it became clear that Aronofsky had a Batman opportunity, bringing Miller onboard for that seemed like a natural fit as well.

With the writing team set, Miller and Aronofsky set out to explore Batman in ways we had never seen on film before.

Major origin revisions

Everyone knows Batman's origin story. Bruce Wayne is the son of extremely wealthy parents who are gunned down in Crime Alley when he's just a boy, so he swears to wage war on all criminals, uses his inherited fortune to build a sweet cave full of gadgets, and eventually becomes the Caped Crusader. That's the way things go, more or less, in Miller's Year One comic book too, but when it came time for the Aronofsky version, the director and the comic book writer decided on a different approach. Together, Miller and Aronofsky started to overhaul Batman's origin story, aiming for a new degree of realism.

"Our take was to infuse the [Batman] movie franchise with a dose of reality," Aronofsky said. "We tried to ask that eternal question: 'What does it take for a real man to put on tights and fight crime?'"

To that end, instead of making Bruce Wayne a young billionaire in the care of a butler named Alfred, they stripped him of his fortune after his parents died, making him a homeless orphan trying to survive on Gotham's mean streets until he was taken in by a mechanic named "Big Al," a stand-in for Alfred. By taking Wayne's toys away, Miller and Aronofsky hoped to get to the heart of what would really drive someone to become Batman.

A much darker Dark Knight

Frank Miller is one of the most influential comic book creators to ever work on Batman, and for many fans his uncompromising, often brutal Dark Knight is the definitive version of the character. Miller's Batman is tough, even relishing his more violent tendencies sometimes, and that influence was felt very clearly on the big screen when Zack Snyder brought the character to life in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Even Frank Miller's Batman has limits, though, and Miller saw those when working on Year One with Aronofsky. The young filmmaker, eager for as much realism as possible, was pushing the Caped Crusader into the realm of the savage, to places even Miller didn't want to go. Though they apparently had a good working relationship, Miller resisted, and found himself arguing for a softer version of Batman for the first time in his career.

"It was the first time I worked on a Batman project with somebody whose vision of Batman was darker than mine," Miller recalled. "My Batman was too nice for him. We would argue about it, and I'd say, 'Batman wouldn't do that, he wouldn't torture anybody,' and so on."

Familiar foes

One of the great hallmarks of any Batman solo film is its villain. In most cases, from Jack Nicholson's Joker to Tom Hardy's Bane, Batman's adversary is marketed as much or more than Batman himself, to give audiences a sense of the superhero showdown they're about to get when they head into the theater. Aronofsky's Year One was, of course, a different kind of Batman film, so had it been made we wouldn't have seen that kind of showdown marketing. Bruce Wayne's major adversary in the film is corruption within Gotham City, beginning with a dirty cop and working all the way up to the mayor.

That doesn't mean the film would have been without familiar Batman enemies, though. Selina Kyle was set to be a major player, but she would have been "Mistress Selina," who worked in a brothel near the auto shop where young Bruce lived. The film would have set her up as an early version of Catwoman, which would have then progressed to a potential sequel. The Joker, that most cinematic of Bat-villains, was also present, but apparently only in a cameo appearance, as an inmate in Arkham Asylum, waiting for his time to shine.

Dueling Batmen

These days, Darren Aronofsky and Frank Miller working on Batman: Year One seems like the kind of intriguing feature film prospect that would keep the whole internet buzzing for a solid year, but it wasn't necessarily the safest bet back in 1999, and Warner Bros. still wasn't sure exactly which direction they wanted to take the Caped Crusader on the big screen at the time. So, while Aronofsky and Miller kept plugging away at their story, the studio also explored other options. Among them, in 2000, was an adaptation of Batman Beyond, the hit animated series that debuted in January 1999 and featured a successor to Bruce Wayne's Bat-mantle 40 years into Gotham City's future. The studio roped in Remember the Titans director Boaz Yakin for the project, along with Beyond co-creators Paul Dini and Alan Burnett and cyberpunk writer Neal Stephenson. Like Year One, the film never materialized, but these two vastly different versions of the Dark Knight are a clear indicator of just how open Warner Bros. was keeping its options in the days after Batman & Robin.

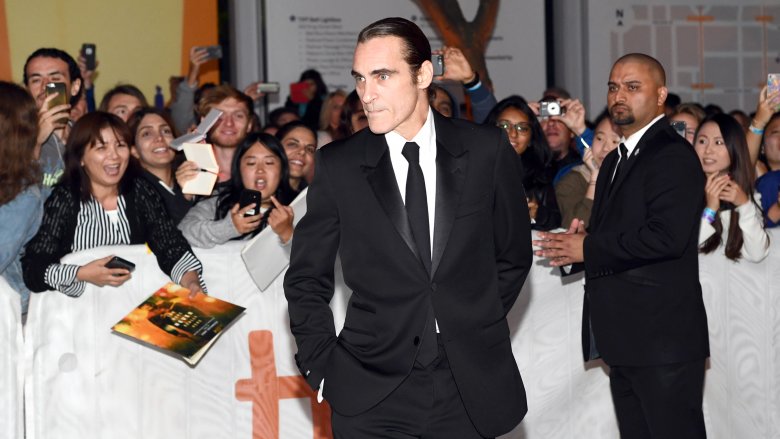

Casting the Bat

Any time a new Batman film is announced, fans immediately start speculating over the casting. Will the studio go with a more daring choice, as Michael Keaton was for Tim Burton in 1989, or will they take the more classical movie star approach we saw with actors like George Clooney and Christian Bale winning the role? Either way, there's always a fierce debate within Batman fandom right up until the film arrives, and then the debate over the actual performance begins. Unsurprisingly, with a daring approach to the story itself, Aronofsky also had a pretty bold choice in mind for the man who would play Bruce Wayne.

"I always wanted Joaquin Phoenix for Batman," he recalled.

In the late 1990s, Phoenix was known for his supporting roles, so while the tonal challenges of Year One might have worked for him, stepping into a leading man role in a superhero movie would have been a major transition. Phoenix never got to play Batman, but he later signed on to play the Joker in director Todd Phillips' origin story for the character, Joker, which hits theaters in 2019.

An uncertain studio

In 2018, it's been proven more than once that R-rated superhero films can be both acclaimed and profitable thanks to hits like Logan and the Deadpool movies, and Warner Bros. even picked up that baton with their Joker origin story movie. In 2000, though, at a time when even Nolan's darker vision of Batman had not yet made it to the screen, a version that took the character to the extremes of Aronofsky and Miller's films wasn't palatable to the studio. In the end, it was just too extreme for a Warner Bros. that was still hoping for a family and merchandising-friendly Batman.

"We hashed out a screenplay, and we were wonderfully compensated, but then Warner Bros. read it and said, 'We don't want to make this movie.' The executive wanted to do a Batman he could take his kids to," Miller recalled. "And this wasn't that. It didn't have the toys in it. The Batmobile was just a tricked-out car. And Batman turned his back on his fortune to live a street life so he could know what people were going through. He built his own Batcave in an abandoned part of the subway. And he created Batman out of whole cloth to fight crime and a corrupt police force."

An audition for bigger things

Aronofsky and Miller's vision for Batman ultimately faded into the background, and became just another chapter in the long journey of development hell that took Warner Bros. from Batman & Robin to Batman Begins. Miller and Aronofsky both went on to other projects, and the film is now an interesting curiosity, but according to Aronofsky there was also an ulterior motive in developing it in the first place: In 2000, he only had two feature films under his belt, and neither of them were big-budget, FX-driven projects, so he used Batman as a way to get to something else — namely his fantasy drama The Fountain.

"I never really wanted to make a Batman film," he later said. "It was kind of a bait and switch strategy. I was working on Requiem for a Dream and I got a phone call that Warner Bros. wanted to talk about Batman. At the time I had this idea for a film called The Fountain which I knew was gonna be this big movie and I was thinking, 'Is Warners really gonna give me $80 millions to make a film about love and death after I come off a heroin movie?' So my theory was if I can write this Batman film and they could perceive me as a writer for it [The Fountain].'"

Aronofsky's gambit paid off — although the Batman project never made it out of development, he did eventually get to make The Fountain, which was released in 2006. While not financially successful, the film maintains a loyal cult following.