Star Trek: 5 Things Only Adults Notice In The Next Generation

"Star Trek: The Next Generation" is considered by many fans of the franchise to be a high water mark. Led by Patrick Stewart as Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the series took the basic premise of "The Original Series" that had premiered more than two decades prior — a starship encountering mind-bending dilemmas on its exploration through the cosmos — and refined it. But those who grew up on the show can often be surprised at how well it holds up. Rewatching "The Next Generation" as an adult unlocks a new way of seeing the series, for better or worse.

While much of the series is every bit as good from an adult perspective (it was, after all, written for a mostly adult audience), those additional layers unlocked through more mature eyes range from the appreciation of themes you might have missed to, on the flip side, patterns that are a bit more concerning. But ultimately, noticing them all can lead to a greater appreciation for one of the most impactful TV shows of all time.

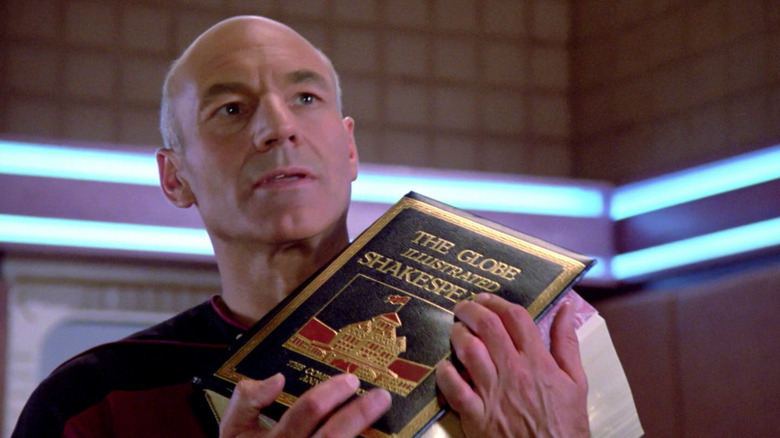

Picard's literary tastes are stuck in the far past

The biggest changes between "Star Trek: The Original Series" and "Star Trek: The Next Generation," weren't in the technologies or ship designs, but the captains. While William Shatner's Captain James Kirk was a brash, swaggering action hero, his successor, Patrick Stewart's Captain Jean-Luc Picard was the polar opposite. Picard was a man of culture who had more in common with a university professor than a naval captain. He drank earl grey tea. He wore sweaters. He quoted Shakespeare.

Speaking of Picard's reading habits, they're very old fashioned for someone from the 24th century. To someone from his time, the authors of the 20th and 21st centuries would feel equally ancient as Shakespeare does to us in the 2020s. But Picard never quotes Virginia Woolf, or Toni Morrison, or James Baldwin. At one point, the series gets close to referencing Raymond Chandler, a mid-20th century writer of hardboiled detective novels, but that's a bit of a technicality, since the title of a Chandler Book is referenced only by the title of the episode, "The Big Goodbye." For the most part, he references the Bard, and elsewhere we get nods to Melville. Admittedly, James Joyce's Ulysses, which the captain reads at one point, was published in 1920, but that's about as recent as his tastes get. Were all the newer books destroyed in World War III?

Struggles of parenthood are a consistent theme in The Next Generation

While Captain Picard may be a perpetual bachelor more married to "Starfleet" than he is to any loved ones — an idea "Star Trek: Picard" would explore in more depth decades later — the struggles of parenting occur as a consistent theme in "Star Trek: The Next generation." Multiple characters on the show either struggle in raising their own children or have complicated adult relationships with their own parents.

The most frequent example is Worf (Michael Dorn), the Klingon Chief of Security onboard the Enterprise, whose child, Alexander (Jon Steuer, Brian Bonsall) grows up in a split family. His mother, K'Ehleyr (Suzie Plakson), is half-Klingon and half-Human, and their cultural differences and work schedules ultimately led to the dissolution of their relationship. As a single father, Worf often struggles to raise Alexander, and the boy initially has behavioral problems as seen in the episode "New Ground." But Worf's crewmates are often happy to help him out, especially Deanna Troi, who counsels the quarter-human child, as seen in the episode "Parallels."

Despite being an android, Data (Brent Spiner), too, has issues with his father-figure, the mad scientist Noonian Soong (also Brent Spiner) who created him. Since Soong was never there, Data feels abandoned, as does his evil twin brother, Lore (yes, Brent Spiner). In one of the most emotional "The Next Generation" episodes, "Brothers," Data is only able to bring himself to call Soong "father" as the man who created him dies in his arms.

The Holodeck has enabled some pervy behavior

Don't shine a black light in there! One of the most creative and futuristic technologies on "Star Trek: The Next Generation" is the Holodeck, which generates holographic worlds so realistic that the things it generates can be interacted physically. So, of course, it has been the grounds for some pretty lude behavior that crosses the line of good taste. In one episode, "Hollow Pursuits," an ensign uses the Holodeck to strike up a romance with a holographic recreation of Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) without the real Deanna's consent. In another, Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) has a creepy romance with a hologram of a Starfleet scientist played by Susan Gibney. And that's only scratching the surface.

What most viewers today will notice is that "Star Trek: The Next Generation" seems more concerned in these cases with the infinite possibilities unlocked by Holodeck technology than it does with the ethics of informed, enthusiastic consent. Of course, many people are thankfully more educated about these boundaries today than they were during the years "The Next Generation" aired, but that hardly lets the confused sexual politics of these episodes off the hook.

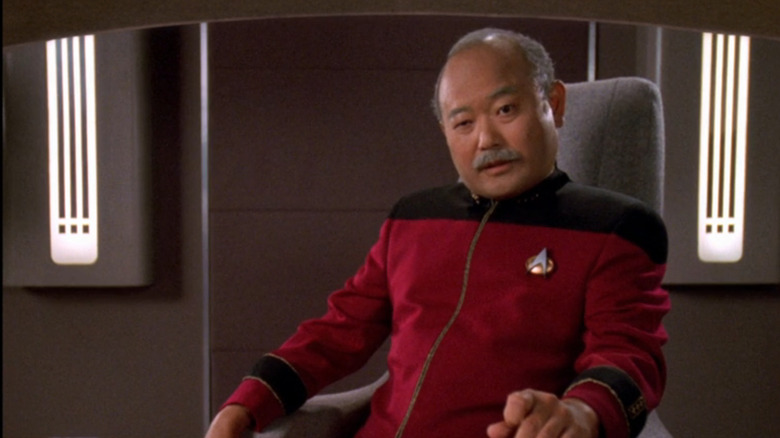

The Next Generation uses some concerning stereotypes

"Star Trek" has always been known for its goals of diversity and inclusion. It has also been celebrated for its inventive alien species, rendered with elaborate makeup and prosthetics. But those who look closely will notice that some of those aliens embody some harmful stereotypes commonly applied to people in real life.

In "Star Trek: The Next Generation," the most notable example is the Ferengi. Introduced in the episode, "The Last Outpost," they are shorter than humans, with exaggerated facial features, sharp teeth, and nasally voices. They're also naturally greedy and obsessed with accumulating money, following a code of laws called "The Rules of Acquisition."

Unfortunately, that depiction mimics harmful stereotypes that have been historically levied against Jews to justify persecution and violence. As Paul B. Sturtevant noted for The Washington Post, many actors who played Ferengi were themselves Jewish.

Later depictions of the Ferengi, such as the beloved Quark in "Deep Space Nine," would go a long way to dispel those connections. But Jewish stereotypes weren't the only ones present in "The Next Generation." Aspects of both Vulcan and Romulan culture appear to have been cribbed from Asian stereotypes, with the former taking on aspects of "model minority" myths which claim Asians are better at academics than their peers and the latter, with their deceptive practices and secret police, embodying Sinophobic fears about the rise of China as a global superpower.

Starfleet doesn't operate like a real navy

Captain Picard shares one major thing in common with Captain Kirk: he loves disobeying direct orders from his superiors and never gets in real trouble for it. Many times on "Star Trek: The Next Generation," Picard is forced to choose between doing the right thing and obeying a commanding officer. Being the goodhearted person he is, he invariably chooses the former, and being incredibly intelligent, he always manages to win the day by doing so. Picard's decision making is almost flawless, which is one of the reasons he's considered such a legendary captain by other Starfleet members.

But while fans love Picard's dedication to ethics at any cost, his continued station as the commander of the Enterprise seems to contradict Starfleet's hierarchical structure, which is based on real-life militaries. And in real life, disobeying an order will get you court martialed or worse. While some armies do have rules preventing someone from obeying explicitly illegal orders (for example, a command to open fire on civilians), most of Picard's renegade actions take place in a gray area where obeying them wouldn't clearly be wrong.

Of course, given that Starfleet is supposed to be at the head of a more evolved society than our own, it makes a bit more sense that they'd come to see reason when faced with Picard's insubordination.