Timothee Chalamet's Wonka Should Have Been A Villain In The Reboot (Which Tim Burton Nailed)

Wealthy entrepreneurs loom large over the imagination of postindustrial society. In the 20th century, it was men like Henry Ford, who revolutionized manufacturing. Today, it's men like Elon Musk, titans of technological achievement. In this cultural milieu, one name towers above them all: Willy Wonka, the amazing chocolatier. Here is a man who was raised in poverty and built his company from the ground up, revolutionizing the candy business in the process. Like Musk, his inventions are so technologically advanced, they seem like magic. Like Ford, his factory has cracked the secret to production on an unprecedented scale.

But like all great men of industry, Wonka harbors a dark side. He exploits laborers imported from the Global South. He's paranoid of his competitors to the point of delusion, and privately seethes at their existence. Workplace injuries are routine in his massive factory, and he allows no one in or out, including government inspectors.

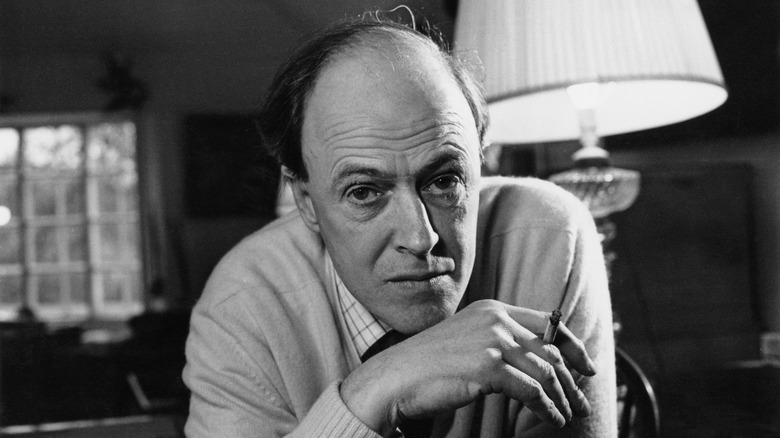

Were Willy Wonka a real person, so might begin a best-selling biography. When you read between the lines, even the original work of fiction by Roald Dahl doesn't paint him in a strictly positive light. So why is it that Hollywood always wants to turn him into a hero? Our latest rework of the character comes courtesy of "Wonka," starring Timothee Chalamet as the self-made cocoa magnate, and it seems likely that the filmmakers have woefully misunderstood the character.

Surprisingly, there is one movie that nailed Wonka as Dahl intended: the Johnny Depp-starring 2005 film directed by Tim Burton. The new movie looks to be ignoring Burton's take, but it shouldn't have. In doing so, it will leave behind the most important message Dahl had to offer.

Roald Dahl focused on inequality in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

While Burton's "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" was received well, most people tend to quickly assert their preference for Mel Stuart's 1971 effort, "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory." It's easy to see why. Gene Wilder, the latter's star, was among the most beloved actors of his generation, with a wide, disarming smile and an affability that left audiences with no choice but to adore him. His Wonka, though, is not the person Roald Dahl created.

The Stuart directed film ultimately depicts Wilder's Wonka as a benevolent person, someone searching for a bit of good in a world of greed. One explanation for this is that Stuart's film was a corporate endeavor. The company responsible for real-life Wonka candy funded the film (hence why the movie's name was changed), and it wanted a character that would endear children to the brand, not repel them. This understandably angered Dahl.

Burton's movie is far more faithful to Dahl's book, which is focused on the economic inequality of its fictional world. At the novel's outset, Dahl emphasizes the economic hardship of the Bucket family. Mr. Bucket works for pittances at a toothpaste factory — toothpaste, of course, being necessary to prevent chocolate from rotting one's teeth — and the book notes, "However hard he worked ... [Mr. Bucket] was never able to make enough to buy one-half of the things that so large a family needed."

And where does Wonka figure into this? His factory sits on the other side of town, with "huge iron gates" and a "high wall," a grotesque contrast to the poverty around it. We are told that its presence "tortured Charlie," who can only afford one candy bar a year. It is nothing short of a maleficent presence. There's no room for Wilder's geniality here.

Johnny Depp played Wonka like the monster he's meant to be

Among its many perplexing changes to the source material, Stuart's film conveniently writes Mr. Bucket out, eliding the need to address the themes of inequality the book focused on. Contrastingly, Burton's effort not only depicts Mr. Bucket (Noah Taylor) faithfully, but also adds a modern twist: his job is being replaced by a robot.

In the opening shots of "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory," Burton shows us the candy-making process, much like Stuart's did. However, as a Wonka truck passes Charlie (Freddy Highmore) on his way home, we see the ramshackle Bucket house juxtaposed against the massive factory chimneys at the other end of town. Later, as Charlie and his fellow contest winners enter the factory gates, the building casts an ominous shadow over them all, swallowing them into its maw. And then we meet him: Willy Wonka, the amazing chocolatier. Animatronic candy-making children sing a song introducing him before slowing like a demonically possessed record player and bursting into flames, portending the fate of his contest winners.

Depp plays Wonka as a sinister presence whose reactions to the multifarious "accidents" that befall the children range from dispassionate to gleeful. After Augustus Gloop (Philip Wiegratz) is sucked into a pipe, Wonka assures his mother (Franziska Troegner) that he won't be made into fudge for the simple reason that, "No one would buy it," another quote from the book that openly displays Wonka's pure capitalist greed.

For the reboot this year, we've got the story of a young Wonka headed our way, with Timothee Chalamet wearing the purple top hat. So why does it seem like, once again, Warner Bros. insists on defanging the darker edges of the story?

Timothee Chalamet's Wonka seems a bit too nice

Warner Bros. Discovery's Timothee Chalamet-starring "Wonka" comes to us helmed by "Paddington" director Paul King. Charming though both that movie and its sequel are, it's hard to imagine the man who gave us the gentle story of a little talking bear will find the grit to depict Willy Wonka as Roald Dahl intended, as a craven businessman who presents an exterior of childish wonder to the world. Nor does Chalamet seem to be playing him with that in mind.

Maybe King will surprise us. After all, "Wonka" is a prequel, and it could be the story of an enthusiastic young man who follows his passion into riches, only to discover that financial success requires an abnegation of the conscience. Sadly, the film's promotional materials don't hint one bit at a darker side to its character, and while Chalamet has played somewhat bratty young men in movies like "Little Women" and "Don't Look Up," he's never played someone with a streak of real evil.

The trailer does suggest a few things, though. Most importantly, it retcons the Oompa Loompas. Chalamet's Wonka accuses Hugh Grant's Oompa of following him, implying that this version of Wonka did not invade an undeveloped nation to exploit them for labor. While that aspect of Dahl's book and its retellings have by now been acknowledged as racist colonialism on the author's part, to do away with it seems less like a correction and more like a whitewashing. Why address hard topics when you can avoid bringing them up at all? Why critique colonialism when your version of the story can pretend it never existed? But that might even be excusable, if only Wonka remained himself.

Chalamet's nice guy Wonka doesn't fit our current day

The most perplexing aspect of "Wonka" is that it will be released during a time when society is pretty much fed up with the owning class and their never-ending efforts to make everyone else revere them. Labor strikes have swept the nation like wildfire, from Hollywood's WGA and SAG-AFTRA to auto workers in the UAW. Last December, as reported by NPR, a massive rail workers' strike was narrowly averted through the use of legislation only because President Biden made their action illegal, and in August, the New York Times reported that a UPS strike was dodged when the company handed over a new contract rather than risk a supply chain breakdown. On a smaller scale, unions are forming at companies including Amazon, Starbucks, Trader Joe's, and more.

In 2005, before the Great Recession, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the economic hardship so many suffered during the COVID-19 pandemic, it's easy to see why Burton's "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" didn't get the reception it deserved. Were it released today, it would likely be hailed for its willingness to question the mythmaking undertaken by the billionaire class.

Guys like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg won public favor at the start of the century by pretending, like Willy Wonka, to be eccentric inventors concerned with bestowing their magical creations onto humanity. That façade is rapidly crumbling, leaving bare the truth that they would turn us all into fudge if only there were a market for it. Like a cavity brought on by too much chocolate, their products have, in many instances, rotted the social fabric of society. Tim Burton understood that, crafting what might go down as the only Wonka film that truly understood Dahl's work.

Wonka feels more like corporate branding than art

Instead of building on Burton's accomplishment, we are getting "Wonka," a film that seemingly wants to reinforce those myths. It wants Willy Wonka to be the lovable candy man he brands himself as, ignoring the darker heart of Dahl's material. In this version, the Oompa Loompas find him, not the other way around, and they're played by Hugh Grant. Little Willy is a kid with dreams who goes from rags to riches, played by America's newfound boyish sweetheart to drive the point home.

In trying to understand why Warner Bros. Discovery may want to avoid Burton's depiction of Wonka, perhaps we should look to its head. Current CEO David Zaslav, who took over the newly merged studio in 2022, was a driving force that pervaded the doom-and-gloom among Hollywood workers in the days before the current strikes. His tenure at one of Hollywood's most historic studios has been defined by moves to shelve nearly completed movies for tax write-offs and gut original television programming, which generated a lot of anger among Hollywood professionals.

You may protest that "Wonka" is a silly movie about a guy who makes candy. Candy that makes people float! How can it be expected to contend with important social issues? Can't we just let it be escapist fantasy? The answer is that it can — and should — be both. Movies are written by people, and people exist in the messy tapestry of society. At its best, art reflects that reality back to us through a funhouse mirror and a river of chocolate. But at its most cynical and banal, it acts like a tour of a candy factory, offering nothing but a sugar high.