Bizarre Hollywood Deals That Happened Behind Closed Doors

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

It takes a lot to get a movie or television show made in Hollywood. So many things have to go right. You need the right idea at the right time with the right producer who's in the same SoulCycle class as the right director who happens to be owed a substantial poker debt by just the right star. And then somebody's got to finance and distribute the thing. Even if you're able to get that recipe just right, there's no guarantee the end product will be a success.

Studios are attempting to mitigate their risks by producing fewer films — largely based on tried and true intellectual properties — and relying on higher ticket prices and consumer product licensing to turn a profit. Competition among TV and streaming services has literally never been greater. That means it's more difficult than ever to get that Hollywood greenlight. As is true with any high risk/high reward proposition, the entertainment industry attracts gamblers willing to go for broke for the chance at making the big deal. These Hollyweird deals can be sealed with a handshake, a cup of coffee, or a case of mistaken identity.

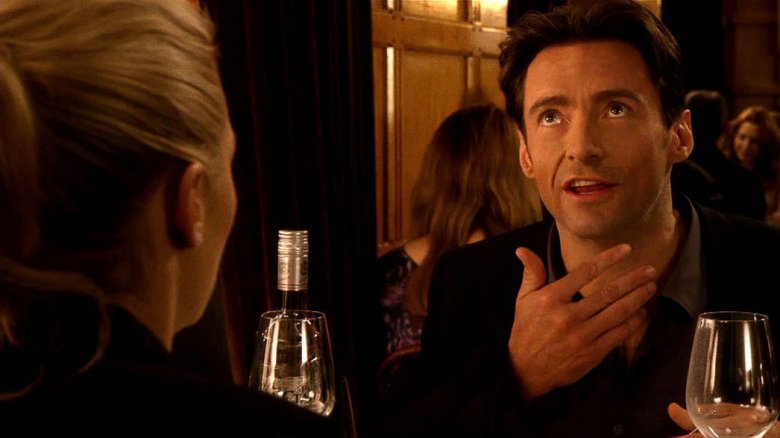

Hugh Jackman and Kate Winslet were unwitting celebrity bait

Movie 43 is a comedy anthology movie, billed as an outrageous, adults-only farce, that came and went from theaters in the blink of an eye in 2013. The movie was destroyed by critics, earning an abysmal Rotten Tomatoes score and being awarded three Razzies, including Worst Picture. Movie 43 earned a little more than $8 million at the domestic box office before being put out of its misery and pulled from theaters. It's almost impressive how poorly this film performed despite boasting one of the most star-studded casts to ever appear in a non-Avengers film. How did this atrocity of a movie that included the likes of Hugh Jackman, Kate Winslet, Halle Berry, Richard Gere, Uma Thurman, Gerard Butler, Naomi Watts, Emma Stone, Kristen Bell, and Johnny freakin' Knoxville manage to come together in the first place?

The movie is a series of 12 standalone sketches linked by the story of three teenagers surfing the web for a banned film called Movie 43. In real life, Charlie Wessler, a veteran Hollywood shark, convinced Hugh Jackman and Kate WInslet to appear in a single sketch for a low-budget comedy movie with the promise of future profit sharing. Over the course of the next four years, Wessler somehow parlayed the existence of the sketch — a shocking short about a character with testicles on his neck — to lure other high-profile stars into signing on, one by one. With extreme persistence, he was eventually able to guilt the stars into shooting their brief scenes. He was not, however, able to convince any of them to do press in promotion of the movie.

Donald Glover 'Trojan-horsed' FX

Atlanta is the surrealist, satirical series from creator and star Donald Glover. The show explores the black experience in America by being at turns hilarious, heartbreaking, and hyperrealistic. It's fair to say that it is wholly original, and there's nothing on TV quite like it. But Glover didn't think that was a very palatable pitch for a new "comedy" series.

"I knew what FX wanted from me," he said in a profile by The New Yorker. "They were thinking it'd be me and Craig Robinson horse-tailing around, and it'll be kind of like Community, and it'll be on for a long time. I was Trojan-horsing FX. If I told them what I really wanted to do, it wouldn't have gotten made."

Stephen Glover, Donald's brother and a major force behind the scenes of Atlanta, said, "Donald promised, 'Earn and Al work together to make it in the rough music industry. Al got famous for shooting someone and now he's trying to deal with fame, and I'll have a new song for him every week. Darius will be the funny one, and the gang's going to be all together.' That was the Trojan horse."

Sony shared Spider-Man with Marvel

When Marvel became a full-fledged movie studio with Iron Man in 2008, it was a risky move. Things seemed to have worked out pretty well for the House of Ideas, but at the time, Marvel Studios was seen as having only a "B-List" character pool to draw from. Fox had X-Men and Fantastic 4, while Sony had the rights Spider-Man. Considering the enormous success Sony had with Sam Raimi's Spider-Man movies, it looked like the web-head would never get his homecoming. However, after more than 15 years, five movies, and $4 billion in worldwide box office, the studio had run into a creative rut with Spidey, and desperately needed to breathe life into one of its most valuable franchises.

In 2015, Sony's top executives, Amy Pascal and Michael Lynton, flew to the Palm Beach, Florida, to the home of Marvel Entertainment Chief Executive Isaac Perlmutter. Perlmutter had seen the writing on the wall-crawler, and, knowing Sony's film division was in trouble, had been making overtures for months. Sony was vulnerable, but would they be willing to share their prized IP with Disney-owned Marvel Studios, a major rival? Lunching at Perlmutter's posh residence, the power players negotiated budgets, sequel possibilities, and determined how Spider-Man would fit into the larger Marvel Cinematic Universe.

The deal they struck is a truly remarkable, in that almost no money exchanged hands. The deal allows Marvel to have total creative control over the Spider-Man movies. Sony pays for the movies and keeps all the profits. Marvel benefits by owning the lucrative merchandising rights for Spider-Man, and is able to include Peter Parker in their Avengers storylines.

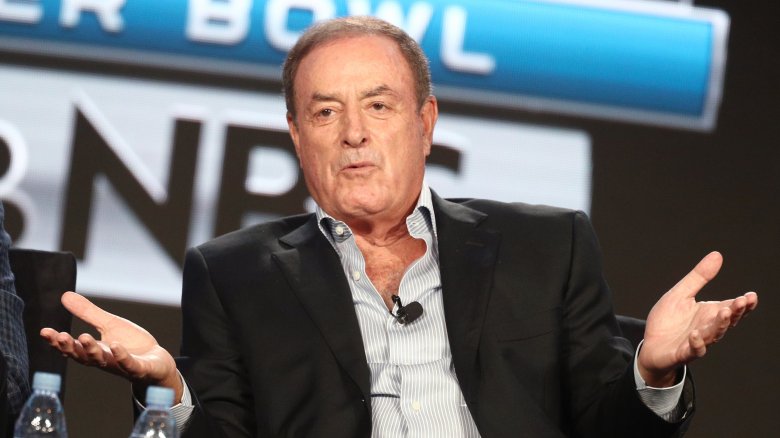

Disney traded Al Michaels for a cartoon rabbit

In 2005, Disney-owned ESPN acquired the rights to Monday Night Football, at exactly the same time that Universal-owned NBC acquired the rights to Sunday Night Football. Famed sportscasters John Madden and Al Michaels had been calling Monday Night Football together on ABC for a few years, but Madden's contract was up, and he headed to NBC. Al Michaels stayed on at MNF, but it was no secret that he wanted to get out of his contract and join Madden in the booth at SNF.

According to former ESPN president George Bodenheimer, Disney's CEO Bob Iger was willing to talk about letting Al Michaels go... on one condition. Iger wanted Oswald the Lucky Rabbit back. Oswald was Walt Disney's forerunner to Mickey Mouse, designed by Disney himself in the 1920s while working for Universal. Bodenheimer recalled his conversation with Iger. "I'd be willing to let Al Michaels go," said Iger, "if you can get us the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit from NBC." Bodenheimer responded, "Who or what is Oswald the Lucky Rabbit?" After a few more phone calls, a real human broadcaster was traded for an 80-year-old cartoon character.

Schwarzenegger tricked Stallone

Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot is a 1992 buddy cop comedy starring Sylvester Stallone and Estelle Getty of Golden Girls renown. It is an all-time clunker of a movie, with a single-digit Rotten Tomatoes score and a paltry showing at the box office. For years, Sylvester Stallone has been saying in interviews that he only took the role to spite his rival, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who he believed had interest in the film. In a Page Six anecdote, Sly described his professional (and often personal) rivalry with Schwarzenegger during the height of their '80s and '90s action film heyday. "Did you ever have someone you wanted to strangle every day?" Stallone elaborated. "It got to the point where we stopped talking to each other and couldn't be in the same room."

At an appearance at Beyond Fest in 2017, Arnold confirmed the longtime rumor. Schwarzenegger recalled, "So I went in — this was during our war — I said to myself, I'm going to leak out that I have tremendous interest. I know the way it works in Hollywood. I would then ask for a lot of money. So then they'd say, 'Let's go give it to Sly. Maybe we can get him for cheaper.' So they told Sly, 'Schwarzenegger's interested. Here's the press clippings. He's talked about that. If you want to grab that one away from him, that is available.' And he went for it!"

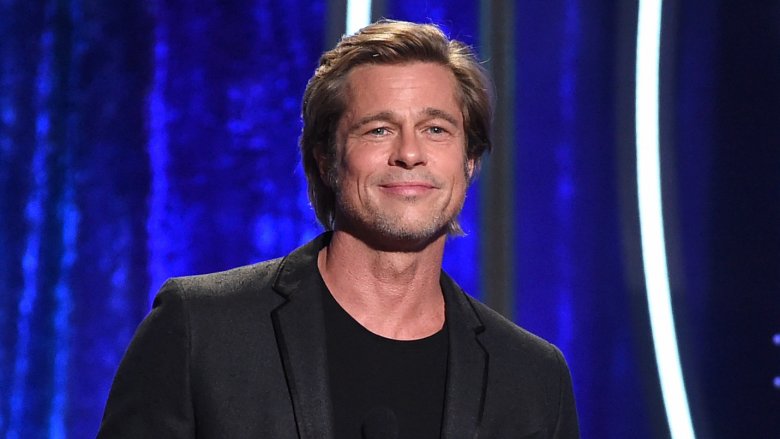

Deadpool wasted Brad Pitt

"What's the most wasteful way to use the biggest movie star in the world?" Ryan Reynolds asked himself. Even if you've seen Deadpool 2, you may not have noticed Brad Pitt's blink-of-an-eye cameo as an invisible character called the Vanisher. Initially, Pitt was in talks for a much larger role in the movie: Cable. Deadpool 2's director David Leitch described how close Pitt was to the role. "We had a great meeting with Brad, he was incredibly interested in the property. Things didn't work out schedule-wise. He's a fan, and we love him, and I think he would've made an amazing Cable."

While Pitt didn't ultimately wind up as Cable, his love for the Deadpool universe left the door open for an another role. Leitch said Pitt left the door open by saying, "If you guys ever need anything give me a call, I'd love to be involved,' and Ryan just said, 'Oh I have an idea.' So we started to think about what it could be and the Vanisher thing was perfect." Reynolds has said that Pitt was paid a single cup of coffee for acting services rendered.

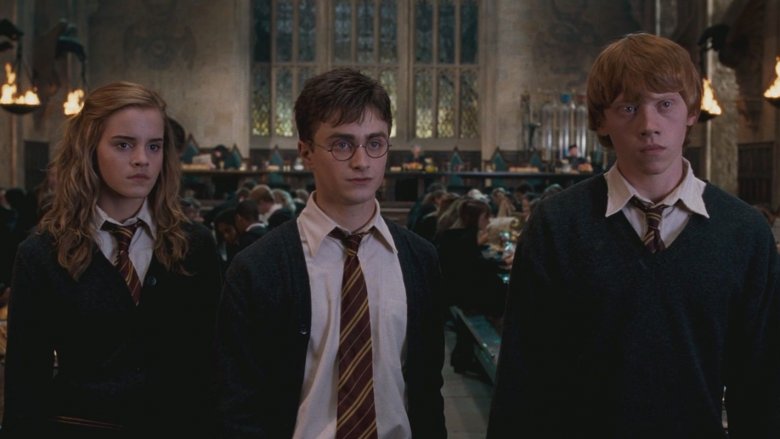

Harry Potter actors got stiffed by contract language

Movie contracts often promise "points on the back end" in order to potentially bolster an actor's salary if the movie performs well. Many studios, however, utilize tricky language and creative accounting to make a movie appear to be a loser on paper — even a movie as big as Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Though the film earned $938.2 million in worldwide box office, according to a leaked Warner Bros. accounting statement, the film actually wound up being $167 million in the hole. Studios will cite things like distribution costs, ad spending, and interest to make a movie look like a dog on paper and avoid paying out back end profits to actors.

Unfortunately, this sort of thing is common practice in Tinseltown. Studios will set up a unique corporation specifically for the production of a given movie. Like any company, this corporation determines its profits by subtracting expenses from its revenues. In order to erase any possible profit, at least from an accounting perspective, the studio then charges this unique corporation a big fee that overshadows the film's revenue. So remember kids, when you're singing that big contract with back end points, make sure they're based on the theatrical gross and not the net profits.

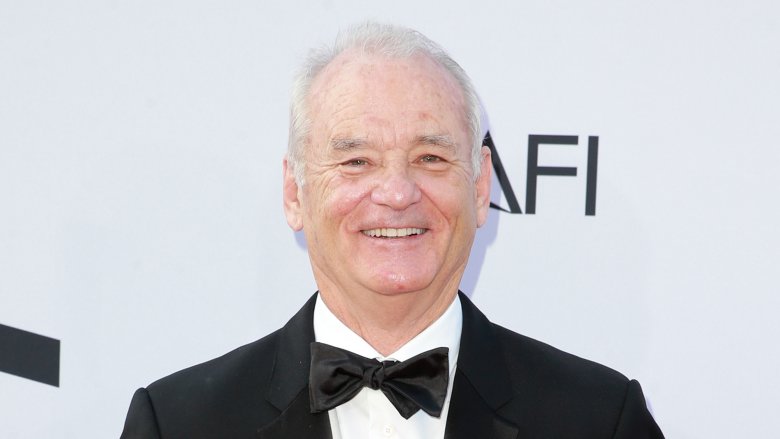

Bill Murray was confused about Garfield

In 2004, at the height of a Bill Murray renaissance and just after his Golden Globe win for Lost in Translation, Murray made a very interesting career move. He signed on to be the voice of the eponymous lasagna-loving cat in Garfield. The movie made bank at the box office, relying on Murray's star power and cutesie animation, but was a failure creatively and critically.

Why would Bill Murray have lowered himself to an uninspired kids movie in the middle of a career upswing? Turns out, it was purely a case of mistaken identity. In a Reddit chat, the actor revealed that he was confused. When Murray got the script, he didn't bother to read it because he saw it was written by Joel Cohen. Joel Cohen is the writer of other family films like Cheaper by the Dozen and Daddy Day Camp. Bill Murray incorrectly thought the writer was Joel Coen, one half of the Coen Brothers, auteur creators of such critically acclaimed movies as The Big Lebowski and Fargo.

Murray is also famously impossible to get a hold of. He doesn't have an agent or a lawyer. In fact, if you want to pitch him a project you have to dial a 1-800 number and leave a message. So, once Murray decided he was going to voice Garfield, it wasn't until he was in the booth recording his lines that he realized the extent of his error.

Jay Leno eavesdropped on NBC executives

In 1991, Johnny Carson, the host of NBC's crown jewel late night franchise The Tonight Show, announced he would be retiring from the show after a nearly three-decade run. David Letterman hosted a popular and groundbreaking talk show, Late Night, that followed Carson's hour nightly on NBC. Jay Leno was Carson's well-regarded and reliable guest host, who performed well whenever Johnny took a break. Both Leno and Letterman wanted to stake their claim as heir to Carson's late night empire. And so began the Late Night Wars of the early 1990s.

New York Times writer Bill Carter wrote a book about this period of time called The Late Shift, which eventually became an HBO movie. The book and the film depict Letterman as the surly genius and heir apparent, while painting Jay Leno as a corporate shill willing to do anything it took to get the hosting gig of his dreams. One of the most memorable stories from Carter's narrative described a time Jay Leno hid in a closet to listen in on a conference call with all of NBC's top executives about Carson's replacement.

Reportedly, Jay sat in the closet and took extensive notes to get a leg up on Letterman. From The Late Shift: "(Leno) had taken notes on all of it, and now he had specific quotations on what people thought of him and his show. Best of all he knew exactly who was for him and who was against him." Years after this story came out, Leno confirmed its veracity, saying that at the time he didn't have an agent or manager, and that listening in to those calls was what got him the job as host of The Tonight Show.

Closed-door Hollywood deals are nothing new

Hollywood has always been a place for closed-door deal making. It's practically in its DNA. When the studio system first came about, big studios had a virtual monopoly on the movie business. Each studio had exclusive contracts with actors and directors, owned the theaters that showed their movies, plotted with each other to control how and where movies were shown, and owned the film processing companies.

When the Justice Department began taking action to break up the studio system in 1930, studio moguls came up with a closed-door deal that went all the way to the top. They found a sympathetic ear in incoming President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. The movie barons claimed the nation needed the film industry as a relief from the troubled economic times. Roosevelt agreed and took action to delay the Justice Department's legal maneuvering, using the National Industrial Recovery Act as justification. The delay wouldn't last long, however, as a new lawsuit was brought against the studios in 1938. This eventually led to a partial dismantling of the studio system, which had the unintentional effect of fueling a young television industry.