Reservation Dogs Star Calls Watching Killers Of The Flower Moon 'F-Ing Hellfire'

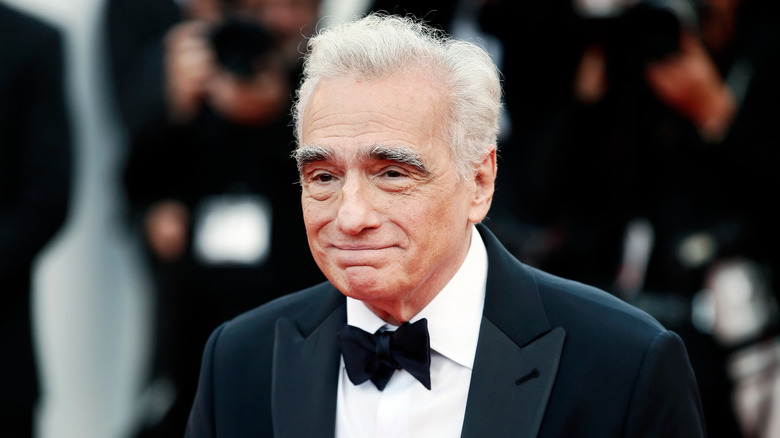

Martin Scorsese's long-awaited adaptation of "Killers of the Flower Moon" is finally out in theaters, adding another huge film to the director's extensive filmography. "Huge" is putting it mildly, too, as the historical Western drama clocks in at just under three and a half hours. Honestly, it's a "Zack Snyder's Justice League" runtime for a movie that couldn't be more different in content and genre. While the film has already earned significant praise from many mainstream critics and cinephiles, it's also garnered some strong criticism.

Like the book of the same name by David Grann, "Killers of the Flower Moon" chronicles the vile murders of Osage Nation members after oil was found on Indigenous land in Oklahoma during the 1920s. The story is sickening and yet another instance of the violence committed against Indigenous peoples in the name of greed and colonial conquest. Although Scorsese's film is clearly meant to condemn this murderous history, several Indigenous-Americans have taken issue with the angle and tone of his film.

One notable name who's critiqued its format is "Reservation Dogs" star and ascending Hollywood writer-producer Devery Jacobs. A First Nations actor who grew up on Mohawk land, Jacobs took to X, formerly known as Twitter, after seeing "Killers of the Flower Moon" to share her thoughts. She critiqued the film extensively, calling it "f***ing hellfire" to watch as a Native viewer.

Devery Jacobs argues for better Indigenous representation

Even though she had immense praise for Indigenous star Lily Gladstone's performance and acknowledged the "compelling" production design of Scorsese's $200 million film, Jacobs found issues with the movie's narrative perspective. "If you look proportionally, each of the Osage characters felt painfully underwritten, while the white men were given way more courtesy and depth," Jacobs wrote. "I don't feel that these very real people were shown honor or dignity in the horrific portrayal of their deaths. Contrarily, I believe that by showing more murdered Native women on screen, it normalizes the violence committed against us and further dehumanizes our people."

Scorsese and his team worked closely with Osage consultants while developing and shooting the film — though none of them were given screenwriting credit or a larger production role. "It's a different movie than the one [Scorsese] walked in to make almost entirely because of what the community had to say," Gladstone told Variety in January 2023. "The work is better when you let the world inform the work." Still, all four of the film's producers, both credited screenwriters, and the director are all white men. Author David Grann is also white.

"I can't believe it needs to be said, but Indig ppl exist beyond our grief, trauma & atrocities," Jacobs wrote on X. "Our pride for being Native, our languages, cultures, joy & love are way more interesting & humanizing than showing the horrors white men inflicted on us."

What have other Indigenous commentators said about Killers of the Flower Moon?

The reception to "Killers of the Flower" from Indigenous Americans and First Nations members has been somewhat mixed. Several prominent members of the Osage Nation have stood proudly by the film, and many worked on it in various capacities. Speaking with Today, Osage Nation Congress member Brandy Lemon shared her experience working as a liaison for the production team. "They actually listened to us," Lemon said. "We weren't considered what people say 'token Indians.' They saw us as people." Also speaking with Today, Addie Roanhorse, great-great grandaughter of Osage murder victim Henry Roan, said that she felt the world wouldn't have believed or paid attention to the story as much without the clout brought by a famous director. "It took a Martin Scorsese to come along, that sort of powerhouse, to tell the story properly, and how he approached the community and how he worked with all of us, we just felt included."

Still, while many Osage Nation members have expressed a sense of closure that the film has brought, not everyone agrees. Osage language consultant Christopher Cote worked on the film and criticized the focus on Leonardo DiCaprio's Ernest Burkhart character in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. "Martin Scorsese, not being Osage, I think he did a great job representing our people, but this history is being told almost from the perspective of Ernest Burkhart," Cote said. "They kind of give him this conscience and kind of depict that there's love. But when somebody conspires to murder your entire family, that's not love. That's not love, that's just beyond abuse."

Who gets to tell stories in Hollywood?

There was a point in time when simply shedding light on the atrocities committed against Indigenous communities and cultures might have been viewed as a progressive move. Fortunately, representation is a much more nuanced issue these days. The stories themselves aren't always as important as who gets to tell them. And in the case of "Killers of the Flower Moon," despite involvement from the Osage Nation, there's no question that the creatives in charge were mostly white and that bias has been felt by some viewers.

"This is the issue when non-Native directors are given the liberty to tell our stories; they center the white perspective and focus on Native people's pain," Devery Jacobs wrote in her thread on X. By contrast, Jacobs' own "Reservation Dogs" has received high praise for its complex and nuanced portrayal of Indigenous life. "I would prefer to see a $200 million movie from an Osage filmmaker telling this history, any day of the week," the actor wrote. These days, Indigenous directors aren't afforded the luxury of that kind of a budget.

Looking simply at "film buff" circles online or the Rotten Tomatoes scores, you might be convinced that "Killers of the Flower Moon" is a clear victory. Of course, the reality is far more complicated. While not all Indigenous (or indeed Osage) voices seem to agree on the movie, one thing is clear: The more that marginalized groups are empowered to tell their own stories, the stronger those stories become. As Jacobs writes, "After 100 years of the way Indigenous communities have been portrayed in film, is this really the representation we needed?"