Movie Cliches We Can Never Escape

Long before reboots, sequels, and cinematic universes took over Hollywood, the major studios made a habit of recycling content—they just did it much more subtly. In fact, some of the same storyline elements have resurfaced in pretty much every genre. Here are just a few examples of movie clichés we'll never escape.

The geek who gets help from the popular kid

The '80s had Can't Buy Me Love, the '90s had She's All That, and the 2000s had The DUFF. Hollywood has always loved the idea of popular kids giving geeks the ultimate makeover for whatever reason. Usually it's a mean-spirited bet or some type of guilt-based obligation, but regardless, it's always a ludicrous fantasy. Cliques exist as the coping mechanism teens use to shield themselves from the superficial and often cruel world of adolescent social interactions. Mean Girls took this concept turned this on its head with some pointed satire. Not Another Teen Movie blatantly parodied several aspects of young adult films, but leaned heavily on this particular cliché focusing on the hilarious presumption that an objectively beautiful girl becomes an undateable mess when she puts on glasses and a pair of overalls. It's obviously wrong, but it's not likely to go away anytime soon. And with social interaction moving almost entirely online, we're probably due for a movie in which a Vine star teaches a struggling Snapchat user how to boost their followers.

The Sadistic Boss

The cliché of the nightmare boss is so ubiquitous that the writers of Horrible Bosses felt comfortable basing the entire plot around this character— a relentlessly evil and wholly unlikable S.O.B. Boss revenge formed the basis for the plot in Nine to Five and Swimming with Sharks, but more often, the domineering overlord is played for a side gag, like in Office Space or Tropic Thunder. Either way, you can bet if there's a work situation in a movie, there's a dick boss. Meryl Streep even won an Oscar for her performance in The Devil Wears Prada even though that movie literally tried to redeem her character's rotten soul with a monologue about how fashion serves some type of benevolent purpose. The awful boss character is such a staple that 21 Jump Street even had two of them, with Nick Offerman and Ice Cube both reading their rookie recruits the riot act. It takes a special kind of cliché to repeat itself within one movie.

The action hero who reluctantly returns to his past for one last job

For some reason, Hollywood writers think audiences need to see their heroes being dragged back into the action against their will. It's not enough that they're going to lay waste to dozens of bad guys (and probably rescue a beautiful damsel in distress). No, they have to first be persuaded away from helping Buddhist monks build wells, like in Rambo III, or lovingly teaching their cousin the art of war, like in Troy. Korben Dallas had put his mercenary past behind him when the fate of the universe crashed through the roof of his cab in The Fifth Element, and John Spartan was wrongfully frozen in a cryoprison for his heroics in Demolition Man before being thawed out for one last mission. Next to seeking revenge for a loved one and being in the wrong place at the wrong time, being called out of retirement is the primary thing every former gunslinger needs to avoid. Well, that and arthritis. Jumping out of helicopters is hell on the knees.

Every single character and situation in any Nicholas Sparks movie

Nicholas Sparks movies have become a Valentine's Day mainstay ever since Ryan Gosling destroyed his early adult life pining over a woman he had no clue he'd ever win back in The Notebook. And some variation of that character—a sullen man whose life is meaningless until he gets the girl who appears wrong for him in every way—shows up in every Sparks movie. There are also the damaged parents who have either neglected or inappropriately shielded their kids in some way (The Longest Ride, The Notebook) their kids in some way, not to mention the "other man," who is either abusive (Safe Haven, The Lucky One) or rejected for no good reason at all (The Choice, The Notebook). And don't forget the opulent homes—usually somewhere in the South—inhabited by characters in their 20s (The Choice, The Lucky One, Safe Haven) and appear meticulously appointed and landscaped despite the fact that most people this age live in filthy, crowded apartments with old Ramen crust on the microwave. But more than any of the above, Sparks movies love one cliché most of all: kissing in the rain. Watching these films, it's easy to believe if you aren't soaked to the bone and freezing when you triumph over adversity and finally make out, then you don't truly know what love is.

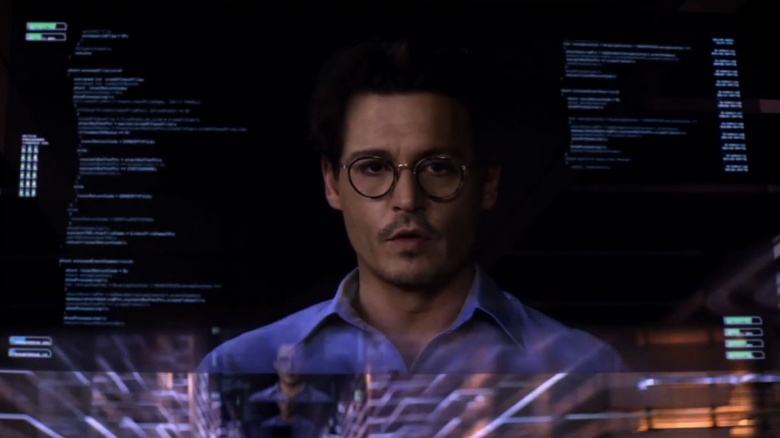

Artificial Intelligence tries to eliminate the human race

According to Hollywood, the instant human beings finally succeed in creating Artificial Intelligence, they're screwed. The inevitable conclusion made by Hollywood's sentient machines is that humans are a parasitic plague on the natural environment. Despite learning the harsh lessons of war, environmental irresponsibility, and political strife, those low-IQ fleshbags known as people keep repeating their destructive behavior, so they gotta go. Skynet from the Terminator series is probably the best-known example of this idea, but it's far from the only one. In The Matrix, the machines destroyed the sun and turned people into comatose batteries. Ultron got creative in his attempt to obliterate Earth's citizens by turning a small Slavic nation into a meteor in Avengers: Age of Ultron, and digital Johnny Depp turned himself into some kind of electrical rain or something in Transcendence. That one was admittedly weird, but the message was the same: Hey, homo sapiens, you had your chance and you blew it.

The scientist nobody listens to until it's too late

Apocalyptic disaster movies make use of tons of clichés, like recognizable landmarks being destroyed or people abandoning their vehicles during end-of-the-world traffic jams to futilely attempt fleeing on foot. There's also usually a scrappy egghead, operating with ancient equipment in some ramshackle laboratory, who has somehow figured out what the rest of the global scientific community has not: The world's about to end. In San Andreas, Paul Giamatti's earthquake prediction algorithm wasn't enough to save most of coastal California, and in Independence Day, Jeff Goldblum was the only person who figured out the insidious nature of the alien crafts hovering over every major city on Earth. Dennis Quaid tried to warn the government of the perils of climate change in The Day After Tomorrow, but they laughed at him. Good thing life doesn't imitate art, or we'd have actual United States Congressmen bringing snowballs onto the Senate floor to dispute real world climate change! (We're all in big trouble.)