The Ending Of Russian Doll Explained

As dark as it is funny, as beautiful as it is tragic, Netflix's wonderfully crafted Russian Doll is certain to become a new classic for fans of genre-defying prestige television. That being said, if ever there was a show that required explanation, hoo boy, is this ever it! Between time travel, alternate realities, and trippy psychedelic hallucinations, it's pretty much impossible to watch this series all the way through without being at least a little bit confused.

Beyond its tangled plot, Russian Doll is also very thematically dense. This series has a tremendous amount to say about mental illness and addiction. It shows the life-changing power that can come when you destigmatize your own mental illness, and how important it is to be able to ask for help when you need it. The strange, seemingly supernatural elements of the story become much more understandable once you realize that they are reflections of these deeper themes.

Like Nadia and Alan guiding each other through the darkest nights of their respective lives, we're here to help guide you through Russian Doll's twisted plot and answer all your biggest questions. There is so much to dig into here, and unlike someone stuck in a loop, we don't have a infinite amount of time on our hands. Let's get started.

Each reset is a new alternate universe

Nadia and Alan die many times throughout the series. They soon get pretty comfortable with this, since each time they die, they seem to jump back in time and start the night over, no harm done.

However, after she dies in the arms of Ruth and sees her loved one mourning over her for a few moments, another, far darker possibility occurs to Nadia — what if each time they die, they are instead just jumping into a new alternate reality? What if each world that they leave behind is continuing on without them?

Although Nadia's hypothesis is never proven, one element of the final episode does support it. In their final reset, our versions of Nadia and Alan find themselves, for the first time, inexplicably reset into two separate timelines, interacting with new versions of one another that don't remember their previous relationship. Since these two distinct realities are shown existing simultaneously over the course of the episode, that definitively proves that parallel universes do exist within Russian Doll's mythology.

Another recurring hint that supports this reading comes in the form of a character — or perhaps multiple characters — played by actor Yoni Lotan. It's easy to miss, but in the first timeline, he plays a sleazy dude that Nadia meets in a convenience store. In later timelines, however, he also plays one of her coworkers, a paramedic, and finally a pedestrian with a unibrow, all clearly meant to be different people.

As Nadia says, "Life is like a box of timelines."

Why do the resets keep getting weirder?

One of the most puzzling elements of the show is that each time that Nadia and Alan die and the universe resets, it's a little bit weirder. Fruit gets more and more rotten, flowers wither, and most chillingly of all, people eventually start disappearing. What's going on?

In an interview with Variety, co-creator and star Natasha Lyonne likened the repeating loops to the life of a drug addict. "Everybody gets a certain amount of chances with getting high in this life," she said. "Some people use them all up really quickly, and then they can continue to get high, but there will be consequences... You can keep doing it, it's just that different aspects of the world as you know it will start falling apart."

The increasingly surreal resets exist to show that, unlike a more classic time loop story — think Groundhog Day, where protagonist Phil Connors has seemingly infinite chances to get things right — the time loop of Russian Doll is unstable. Nadia and Alan don't have forever to figure things out. This is a story about substance abuse and self-destruction. Much like in real life, Nadia and Alan only get so many chances to make mistakes, and each time they fail, more and more of their possessions, their friends, and their worlds vanish around them.

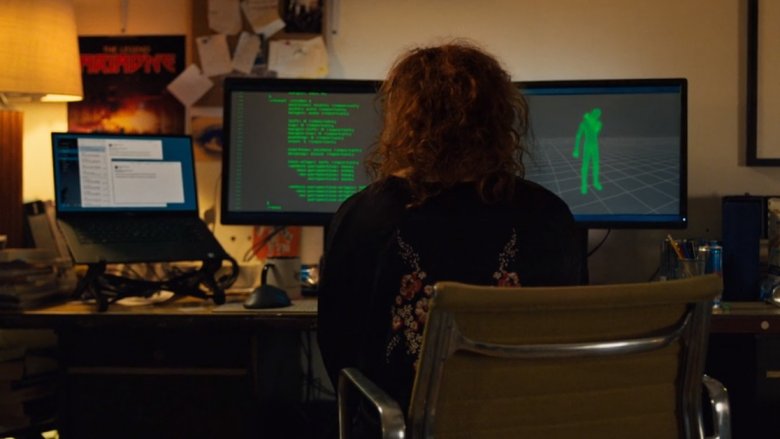

It's all about video games

Nadia is a programmer for video games, and this element of the story offers yet another hint as to what's really going on beneath the surface of Russian Doll. Once you realize the similarities between Nadia's situation and a game, much about the nature of the time loop she is trapped in becomes clear (or, at least, clearer).

Series co-creator Leslye Headland said that she doesn't think of the series as a standard time loop story. Instead, she thinks of Nadia's situation as being much closer to getting trapped in a video game. As she puts it, "What if life treated you way that a video game treats you, which is that you can't move forward until you accomplish this thing, and you're just not allowed to until you accomplish this thing?"

In many video games, levels are designed first to teach you certain skills, and then to test whether or not you've learned those skills. If you've learned what the level is trying to teach you, you can defeat it and move on to the next challenge. If you can't, you die, and then you get sent back in time to the beginning of the level, over and over until you learn your lesson... that is, until you run out of lives.

If the time loop of Russian Doll is inspired by video games, what is this particular game trying to teach Nadia and Alan? What lesson do they need to learn in order to defeat this level?

The final episode is the final exam

There are many lessons that Nadia and Alan need to learn to fix their lives. Nadia needs to care about her long-term health, both physical and mental. Alan needs to value himself as an individual, outside of his relationship with Beatrice. However, neither of these is the real lesson the time loop is trying to teach either of them, because even after they learn these smaller lessons, they still have one more test, and it's the hardest one yet.

In episode four, Alan's friend Farran suggests that Alan see a therapist. Alan insists he doesn't need therapy, that he can do it by himself. Farran replies, "No one can do anything by themselves." Blink and you'll miss it, but that is the underlying theme of the series. All of Nadia and Alan's problems could be solved if they were only willing to ask for help, but they are both too proud to do so. That is the root problem both characters need to fix.

Even after they've learned to no longer be self-destructive as individuals, the final episode is the final exam. This is why Nadia and Alan find themselves in separate timelines, each with a version of the other that has no memory of the lessons they've learned, doomed to die like they did on the very first night — permanently this time, unless someone helps them. It's not enough to learn how to solve their individual problems. Nadia and Alan have to learn to care for others, because "no one can do anything by themselves."

Why is the final episode called Ariadne?

The last episode of Russian Doll is called "Ariadne." This is partially because Ariadne is the name of a ridiculously hard video game that Nadia designed, but that's far from the end of the story.

In Greek mythology, Ariadne is a princess who helps Theseus navigate the labyrinth and slay the Minotaur. Before Theseus, everyone who tried to complete the labyrinth died. Theseus emerged victorious not because he was stronger than the other heroes, but because Ariadne was helping him.

In episode six, Alan says that he tried for months to beat Ariadne, Nadia's video game, but he kept dying because it was too hard. He tells her, "You created an impossible game with a single character who has to solve everything entirely on her own. It's stupid!" Nadia then tries to prove him wrong by beating the game all on her own, and not even she can do it.

Letting go of negative habits, playing a difficult video game, and traveling through a deadly labyrinth all have something in common: your chances of success are much greater if you have help from a friend.

The final episode is called "Ariadne" because in it, Nadia and Alan have to protect alternate universe versions of each other who are at rock bottom, just like the mythical Ariadne protected Theseus as he navigated the labyrinth. The episode shows that true power lies not in wandering the labyrinth alone, but in connecting with others and finding your way out together.

What's up with Horse?

One of the most intriguing yet inexplicable elements of the entire series is Nadia's mysterious homeless friend known only as Horse. The first time Nadia sees him, even before the time loops begin, she says that she thinks she knows him, but can't remember why. At this point, seasoned TV viewers should feel their foreshadow senses tingling. We wait for the ultimate reveal of his secret backstory, his supernatural powers, or his strange temporal significance. But as the series goes on, nothing ever pays off.

On the significance of Horse, Leslye Headland said, "To me, Horse is the god Pan. He lives in the woods in Tompkins Square Park, and he is all of our unconscious or subconscious selves. We can dip in and visit Horse whenever we want."

In mythology, Pan is a god of partying and fun, but he is ultimately untrustworthy — he is a trickster, a force of chaos. Similarly, even though visiting Horse is briefly therapeutic for Nadia, it's also dangerous. At one point he robs Alan, and when Nadia decides to sleep curled up alongside him in the park, she freezes to death. Like many of Nadia's bad habits, Horse ends up being a false promise of happiness, a dead end. Perhaps it's no coincidence that "horse" is a nickname for heroin.

Perhaps disappointingly, Horse ends up being more important symbolically than literally. Much like Nadia's experience hanging out with the character, all our elaborate Horse conspiracy theories have ended in a sad dead end.

Why Emily of New Moon?

Another recurring element in Russian Doll is Nadia's favorite book, Emily of New Moon by L. M. Montgomery. If you haven't read it, you're probably wondering if contains any hints about the series' deeper mysteries. The answer is... maybe? As Nadia would say, "F-ing clues abound."

The respective protagonists of Russian Doll and Emily of New Moon have a lot in common. Both lose their parents as children and have to be raised by a surrogate parental figure. Each saves the life of a friend with the help of supernatural forces. Nadia saves Alan because of the time loop. Emily's "second sight" allows her to save the life of her friend Teddy.

In Russian Doll, mirrors represent objectivity, and the recurring destruction or disappearance of mirrors occurs when a character is slipping into madness. Similarly, Emily's best friend for a time is her reflection, an imaginary friend she calls Emily-in-the-glass.

There are no big answers here, but the weird parallels are endless. Emily has a cat named Mike. Nadia, while searching for her missing cat, has a one-night stand with a man named Mike. It goes on and on. One final tragic similarity that Nadia and Alan share with the real-life author L. M. Montgomery is that all three suffered from mental illness. There is some even some evidence that Montgomery may have died from suicide.

Fortunately, Nadia and Alan were able to find their way out of the darkness, and you can too. If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Do Nadia and Alan end up in the same reality?

In the last scene of the last episode, the screen is split. On one side, we see our Nadia (let's call her Nadia Prime) in one reality, with a new version of Alan whose life she just saved. On the other half of the screen, we see our Alan (Alan Prime) in a different reality, with a new Nadia. But in the final shot, after both pairs pass through two versions of the same street parade, a single Nadia and a single Alan exit the parade together, and the split screen is gone. Does this mean the two realities merged? Was Nadia Prime reunited with Alan Prime?

If you interpret the scene literally, then the answer is yes. The evidence can be seen in their outfits. Earlier in that episode, Maxine tosses her drink in Nadia Prime's face. This leads to Nadia Prime changing into a white shirt. Similarly, Lizzie's friend Jordana puts a red scarf around Alan Prime's neck in his reality. Throughout the episode, Nadia Prime has a white shirt and New Nadia has a black shirt, while Alan Prime has a scarf and New Alan has no scarf.

When only one Nadia and one Alan are together at the end, the Nadia is wearing a white shirt and the Alan has a scarf, indicating that the original Nadia and the original Alan are back in the same reality, perhaps because their test is finally over. That is, if you choose to interpret any of this literally.

More magical than realism

All this being said, attempting to create a list of "rules" for Russian Doll's supernatural or hallucinatory elements is probably missing the point. In most fantasy and science fiction, even if the fantastical elements don't follow real life physics, they at least behave predictably and consistently. The problem is that this series isn't fantasy or science fiction. In interviews, Leslye Headland consistently labels Russian Doll as "magical realism."

Magical realism isn't a particularly popular genre in modern fiction, but it has a long history in literature. Rather than being concerned with fantastical world-building or exploring hypothetical scientific questions, magical realism is strongly focused on the realistic inner lives of a small cast of people, and the rest of the world exists only as an exaggerated metaphorical representation of that inner life. The end results often look like fantasy, but the underlying logic is entirely different. Edgar Wright's adaptation of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and the works of screenwriter Charlie Kaufman are among the more prominent examples of magical realism in modern cinema.

This is not to say that dissecting this series is "thinking about it too hard." Feel free to think as hard as you want! But for your own sanity, remember that Russian Doll has surprisingly little to say about time travel or alternate realities — that's not where the meat is. It has far more to say about addiction, self-destruction, and the value of human connection. If you only analyze it literally, you'll never make it past the snake room.