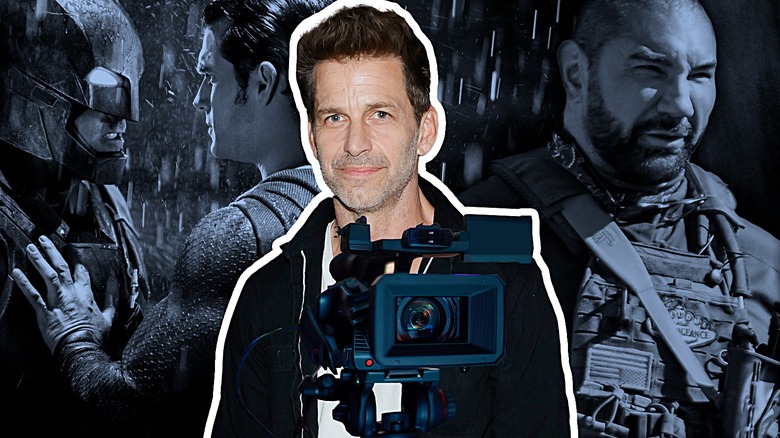

Every Zack Snyder Movie Has The Exact Same Problem

Few directors working today command the polarizing passions that Zack Snyder does. His fans are dedicated — borderline obsessive — to the point that they conjured the most massive and heavily publicized director's cut ever made out of the ether. His detractors are similarly driven, never missing an opportunity to lambast the director's cult-like following or take his movies down a peg.

The longer you stare at the Zack Snyder event horizon, the more bizarre it becomes. His films have been accused of spotlighting fascist imagery and ideals and promoting right-wing political propaganda. And certain subsets of his online superfans haven't helped ease those accusations. But at the same time, in an era when toxic behavior is being increasingly called out in Hollywood, Snyder has rarely been spoken of with anything other than praise by the many creatives who've worked with him.

When "Army of the Dead" actor Chris D'Elia was hit with a slew of sexual misconduct allegations, Snyder excised him from the film entirely and replaced him with a green-screened Tig Notaro. When Ray Fisher was being quietly blacklisted for condemning racist practices within Warner Bros. and DC, Snyder stood by him and continued casting him, returning the actor's "Justice League" character, Cyborg, to a place of honor in the director's cut.

Some may think that any criticism of Snyder is based in his polarizing impact, but for a moment, let's separate the artist from the art. However you feel about the director, all of his movies have the same problem: They can't tell the difference between drama and melodrama.

The myth of Zack Snyder and the Zack Snyder myth

Surely, Zack Snyder fans are already typing — "something something, Marvel doesn't take the source material seriously enough, something something, mature tone." But this isn't a takedown. It's not a hit piece. Snyder's complicated silhouette is more nuanced than most diehards or haters admit. His style, on the other hand, is cut-and-dried. It's drab color grading, excessive slow-mo, and sticky-sweet monologues about gods and glory. It's Rorschach (Jackie Earle Haley) taking a stand and declaring he'd rather die than lie to the people before being exploded by Dr. Manhattan (Billy Crudup). It's dialogue like "Do you bleed? You will."

Some Snyder fans believe that people only hate his movies because they don't understand or unfairly despise this kind of austere filmmaking, that they'd rather giggle along to some committee-written Marvel Cinematic Universe joke. While that may be true for some, the idea that Snyder's tone is simply misunderstood is a myth. It's the idea of myth itself — the desire to portray every character and moment as legendary — that makes his movies unique. The problem isn't that Snyder loves to milk the drama out of big moments. It's that he milks the drama out of every moment, whether there's any inherently there or not.

Drama vs. melodrama

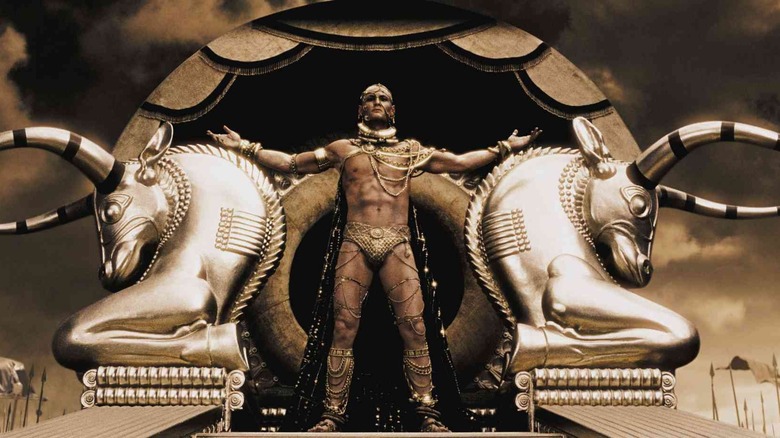

Early in his career, Zack Snyder made movies that conformed neatly to his particular style. His acclaimed remake of "Dawn of the Dead" not only oozes the dramatic but is also decidedly camp. And in "300," he found a story so legendary and mythical that no amount of slow-mo or pit kicks could make it feel ridiculous.

In retrospect, though, these early movies still suffer from the patented Snyder super-seriousness. The characters and story are dictated by the tone instead of the other way around. In every film, he tries to achieve high drama but more often than not, ends up with melodrama — a world where every line, twist, and battle is drenched in equal amounts of severity. The arrival of a zombie queen near the beginning of "Army of the Dead" is treated with the same intense energy as the death of Superman (Henry Cavill). It's all long stares, screams, and superimposed emotions.

There's nothing wrong with dramatic writing or staging, but when every major moment is treated with a similar level of importance, it all begins to feel like mush. Zach Snyder movies are at their worst when they dive so deep into self-seriousness that all contrast is wiped away. Melodrama is meant to create this very effect — blending all emotion in such an extreme way that it wraps around and becomes something else — but Snyder wants to keep both the drama and the constant elevation of it. His contrast often goes from 10 to 11, with no room for a lower number. As a result, his movies can be exhausting to watch, and not just because of their length.

Even the Snyder genre needs room to breathe

One could argue that Zack Snyder's high-intensity, mythical approach to storytelling is simply a genre choice. It's a grimdark, Greco-Roman style with sword-and-sorcery sensibilities. And that's true, to an extent. But even a genre built on drama needs room to breathe, or the big moments start to falter. You need a foundation on which to deliver your payoffs. Remember that scene in "Man of Steel" where Superman gets beer dumped on him and then impales the guy's truck with a telephone pole? It's a moment that screams, "Look how dark this guy can get!" But if a barfight is treated with that much severity, there's little room for the movie to grow once Zod (Michael Shannon) appears.

To be clear, this problem doesn't ruin all of Snyder's movies. Like any director, he has better and worse ones. Patrick Wilson's Nite Owl II in "Watchmen" is a great example of a character who exists outside the pervasive Snyder melodrama. He doesn't see himself as a Greek hero, but rather as a regular guy trying desperately to do the right thing. He provides the contrast necessary for Rorschach to go full grimdark. And despite what the comic's fans may say, the movie succeeds because of that.

Snyder has also made a couple of films that explore less self-serious material, like the wild world of "Sucker Punch" or the family-friendly "Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga'Hoole," and yet the allure of melodrama still pulls him in from time to time. Even the trailers for "Rebel Moon" show a huge cast of characters all scowling from the very beginning. And when half of your movie moves in slow motion, it just becomes a slow-moving movie.