The Ending Of American Fiction Explained

Contains spoilers for "American Fiction"

Because it's only fairly recently that Black filmmakers have been given a platform to tell more diverse stories on screen, there's a familiar discourse that seems to happen whenever their movies come out. Studios have a tendency to gravitate toward the kind of "raw, authentic" storytelling that capitalizes on Black suffering — but while films that tackle slavery and other horrific topics are important, they're hardly representative of the entire Black American experience. "American Fiction," a social satire directed by Cord Jefferson based on the novel "Erasure" by Percival Everett, tackles this complicated dynamic in popular literature.

It stars Jeffrey Wright as Thelonious "Monk" Ellison, a distinguished author and university professor whose novels haven't exactly been flying off the shelves. After being encouraged to write something "more Black," he speed-writes a cliché-ridden novel that capitalizes on every single racialized trope, hoping it will help his agent and publishers realize what a ridiculous and offensive request that is. But, to his surprise, they love it, and the success of the book forces him to compromise his values at every turn.

"American Fiction" was well-received on the festival circuit, even winning the People's Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival. The film is designed to appeal to a wide array of audiences, and it doesn't exactly have a lot of twists and turns. That said, the finale comes a mile a minute, so it's understandable that viewers may have missed out on some of its nuances upon first viewing. Here's everything you need to know about the ending of "American Fiction."

What you need to remember about the plot of American Fiction

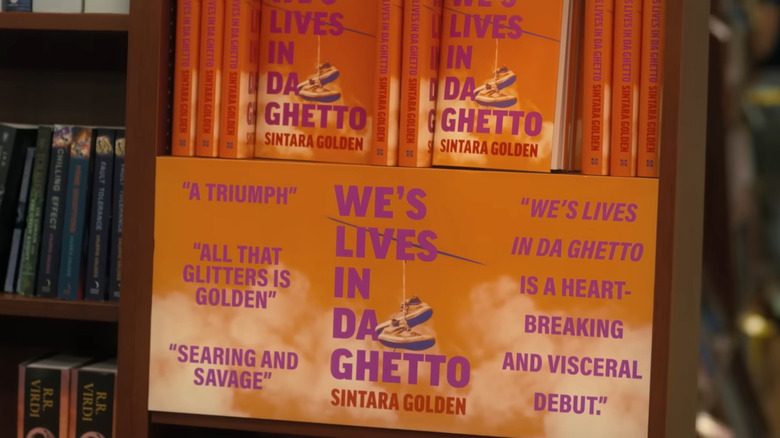

For the most part, Thelonious "Monk" Ellison isn't overly concerned about the success of his novels. He writes what he thinks has literary value, and if that doesn't connect with readers, well ... he considers that more of a "them" problem. But when his sister (Tracee Ellis Ross) dies suddenly and his ailing mother with dementia becomes his primary responsibility, he finds himself needing to publish a hit. His agent Arthur (John Ortiz), noting the recent success of a novel by a young Black author named Sintara Golden (Issa Rae) called "We's Lives in Da Ghetto," essentially suggests that Monk write a book that is "more Black." This confounds Monk, because he is, after all, already Black, so anything he writes is a Black book.

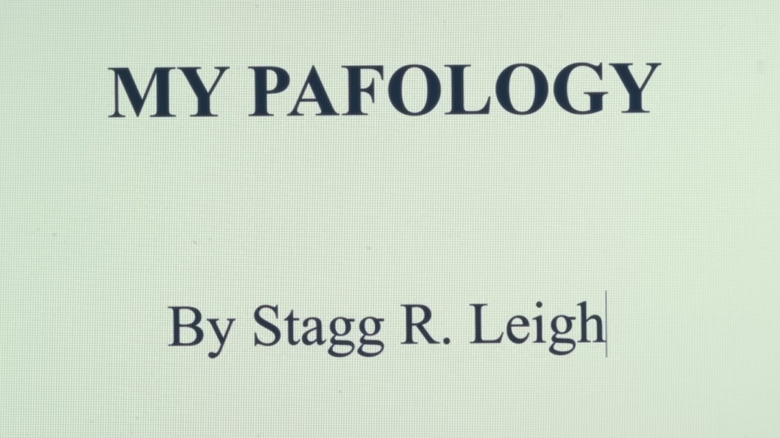

In a drunken fit of pettiness, Monk writes "My Pafology," a story with drugs, gangs, and violence, essentially to mock the tastes of popular audiences. "If they want a Black book," he thinks, "I'll give them a Black book." There's just one problem: The publishers eat it up, and offer him (or rather, his alter ego Stagg R. Leigh, since the book is meant to be autobiographical) a massive deal. Although he tries to sabotage "My Pafology" several times over the course of the film, he ends up getting in way over his head when prestigious literary awards groups, movie studios, and the press come calling.

What happened at the end of American Fiction?

As "American Fiction" draws to a close, Monk is at a New England literary award ceremony. Since his alter ego, Stagg R. Leigh, is about to be honored, it seems like he has no choice but to finally reveal the truth about his identity. He takes a deep breath, walks up to the podium, and begins to confess. But before he can actually say anything, there's a sudden cut, and we see Monk and filmmaker Wiley Valdespino (Adam Brody) on a set, where Wiley is complaining about the proposed ending. It's clear that they're planning on making a film adaptation of the events of "American Fiction," but they're still trying to figure out how to wrap it all up.

After Monk's suggestion of just having the story end as it did in real life is shot down, he comes up with a more romantic ending, where he rushes out of the awards ceremony to make up with his girlfriend Coraline (Erika Alexander). He turns up on her doorstep, saying, "I'd like to apologize — I haven't been myself lately." Get it? Because he's been pretending to be someone else? Wiley's not a fan of that ending, either. Frustrated, Monk comes up with the idea of having his character dramatically shot as the FBI storms the awards ceremony in search of the fugitive Stagg R. Leigh. It's gruesome, over the top, and Wiley absolutely loves it. Looks like we're in business!

What the end of American Fiction means

Although Monk's wild adventure of literary fraud is finished by the end of "American Fiction," he's still grappling with the central issues that made it necessary in the first place. By committing to working with the Hollywood-minded Wiley Valdespino on a cinematic adaptation of his story, he remains immersed in the creation of a less-than-authentic Black narrative.

Monk wonders why the movie can't just end the way that his experience with "My Pafology" did in reality, where he simply left the awards ceremony and went home. Wiley is adamant that audiences just can't handle that kind of nuance, and that they need to come up with a showier finale to make the story really pop on the big screen.

What the at-odds pair ultimately land upon is a tragic shooting where Monk is killed by the police while accepting the award. This brings the entire film full circle. Monk is once again put in a position where he's asked to make his story — and, by extension, himself — "more Black" for an audience that is perhaps most interested in luxuriating in Black suffering.

Why does American Fiction have multiple endings?

While "American Fiction" has a fairly straightforward narrative structure for most of the film, there are several fake-outs at the end that show different ways Monk's story could have concluded — consider this the unconventional but surprisingly effective "Clue" strategy. Part of this is to signpost the central theme of inauthenticity. As Monk and Wiley workshop how the story should end, they strip it of any sense of reality and mold it into what suits the tastes of moviegoers best. A story about a Black man is not sufficient to be seen as a Black story, and the fact that they can't help but sensationalize Monk's experiences speaks to the larger cultural issues that the film is trying to bring to light.

But there's also a more practical reason why the filmmakers may have opted to end "American Fiction" as they did. This kind of film is really hard to write endings for — you usually have to end on an upbeat tone when it comes to comedic satire, which can invalidate the damage of whatever social commentary you were trying to highlight. By having them work through different endings, they are effectively able to sidestep having to come up with an actual conclusion, allowing "American Fiction" to keep some of its bite without being a complete downer.

What happened to Monk?

By the end of "American Fiction," Monk has a much less dogmatic view of what Black literature should look like. His conversations with Sintara have made him realize that there is room for stories about the Black experience that he might consider clichéd or even offensive. Ultimately, it's okay that some audiences might gravitate toward novels that he doesn't feel are representative of life as a Black person in America, since his worldview is not universal. This is made clear by his decision to work with Wiley on a film adaptation of his story, as he accepts the fact that what ends up on screen will likely be an overly dramatized version of events.

As his brother Cliff (Sterling K. Brown) picks him up on set, we see that the two have reconciled and are closer than ever. Right before they drive away, Monk makes eye contact with a young Black actor on the studio lot dressed in costume as a slave for Wiley's plantation-based horror film, who throws up a casual peace sign. Monk gives him a brief nod, which shows a certain amount of character growth. At the beginning of "American Fiction," he likely would have been more critical of a performer in a film that so clearly capitalizes on tragedy, whereas here he shows a more nuanced understanding of the journey that led that actor to take on that role.

Sadly, he hasn't reconciled with Coraline by the end of the film (he tells Wiley she won't return his calls), but there's every chance that he will keep trying and eventually make amends for the chaos he put her through during the events of "American Fiction."

The film satirizes American perceptions of race

Over the course of "American Fiction," we are treated to many examples of moments where well-intentioned people celebrate the kind of racial stereotypes in literature that alienate an upper-class intellectual like Monk. Sintara earns herself a bestseller with a slice-of-life Black narrative that Monk finds ridiculous — he would argue that only focusing on poverty and crime does a disservice to the Black community.

The publishers praise the fugitive wunderkind Stagg R. Leigh for his honesty and no-holds-barred approach to storytelling, excited to give readers a real glimpse of life on the streets, completely unaware that their author is actually a middle-aged, upper-class college professor. The sticking point in all of this is a question of authenticity: This stereotypical view of selling drugs in the ghetto is deemed more authentic to the Black experience than anything in Monk's life, even though, as a Black man, his perspective is equally authentic.

The film ends by turning Monk's entirely anti-climatic departure from the awards ceremony (he literally just gets up and leaves) into a melodramatic, ultra-violent showdown with police where he is gunned down by FBI agents who confuse his award statuette for a weapon. This new conclusion speaks volumes, driving home the point that authenticity is so easily warped into artificiality to appeal to viewers.

How American Fiction holds audiences to account

For white audiences watching "American Fiction," there's an element of being taken to task for their reactions to "Black" films. White viewers are supposed to laugh at the ridiculousness of the book publishers fawning over Monk's work, and how the literary awards committee eats up his clichéd depiction of the Black experience. But, on some level, they are just as eager to celebrate the "right" kind of Black storytelling, to be seen as being in on the joke and therefore more enlightened than the cringe-inducing characters in the film.

The fact that "American Fiction" ends with Monk on a film set helping Wiley create a cinematic version of the story we've just seen is a pointed reminder that its satire is as much a commentary on audience tastes and expectations as anything else. "American Fiction" is not afraid to gently mock its audience, many of whom are no doubt as guilty as any of the characters in the film when it comes to seeking out the kind of entertainment that Monk is so frustrated by.

How does American Fiction differ from the novel?

In 2001, Percival Everett made a splash with his novel "Erasure," which provided a thoughtful commentary on the limiting expectations for Black contributions to literature. "Erasure" unfolds in much the same way as "American Fiction," but there are a few key details that differ. One is the treatment of Monk's sister Lisa — in the film, she has a sudden cardiac event and passes away in hospital. In "Erasure," her death is far more dramatic, as she is murdered by right-wing activists who target her women's healthcare clinic for providing abortions. Her sudden demise is jarring enough in the film, but to have her die so horrifyingly would have cast a somber shadow over "American Fiction" that might have blunted its comedic edge.

"Erasure" also showcases much more of "My Pafology." In the film, we see just a few pages from the novel — as Monk is initially writing it, the characters come to life in his home office and act out the scene that he's working on. But "Erasure" actually has the entire text of "My Pafology," giving the reader a fuller view of the work and developing its satire through that rather than exclusively relying on Monk's perspective. While it works on the page, this approach probably would have been too much for the movie, which is already almost two hours long.

What Cord Jefferson has said about American Fiction

"American Fiction" represents a very special moment in Cord Jefferson's career — while he has written for television for several years, this is his first feature film and his directorial debut, to boot. Jefferson became a huge fan of "Erasure" when he read it in 2020, saying in an interview with NPR, "It felt like it was a book written specifically for me."

Monk's distaste for stories that only seem to capture the bleakest aspects of the Black experience resonated with Jefferson. Beginning his career as a journalist, he grew increasingly demoralized by the constant reports of police violence against Black Americans. "On a weekly basis, they would come to me and say, 'Do you want to write about Mike Brown getting killed?' 'Do you want to write about Trayvon Martin getting killed?' 'Do you want to write about this unarmed Black person getting killed?' It just felt like there was this constant churn of just violence and misery."

As a writer himself, Jefferson felt a kinship with Monk, especially in regard to the inciting event of "American Fiction," when he gets told to essentially write a Blacker book. Jefferson remembers getting a similar note on a project he worked on shortly before reading "Erasure." He explained to NPR, "I got a note from an executive about this script that I had written [and] they said that we want you to make the character in the film 'Blacker.' And so that note came through an emissary, and I told the emissary, 'I will indulge that note if the person who gave you that note will come to me and tell me what it means to be 'Blacker.' And guess what? That note went away."

What Jeffrey Wright has said about American Fiction

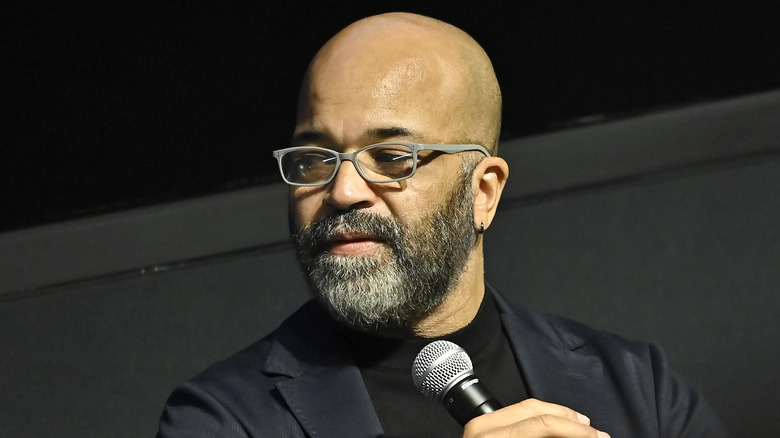

You may recognize Jeffrey Wright as one of the best parts of pretty much every movie or television show he's ever been in, whether it's "Westworld" or "The French Dispatch" or the "Hunger Games" movies — he's just that good. His leading performance in "American Fiction" is one of his most interesting on the big screen, and it's a story that Wright felt emotionally connected to right from the get-go.

As he discussed during an interview with Awards Watch, Wright immediately engaged with the script, referring to Monk as someone who he understood immediately. "I was very familiar with [Monk], very familiar with his challenges, to some extent, from a creative side, but I was particularly familiar with his personal challenges." Wright went on to add, "I understand what he's responding to in terms of the imposition of limitations by larger society onto him."

He had nothing but praise for director Cord Jefferson and the original novel, as well. Wright discussed his excitement to work with a filmmaker who really understood the complexities of the conversation "American Fiction" was interested in having, saying, "I just loved that we were going to have a dialogue around race and language, a dialogue that exists now in American society, but we were going to do it with a level of fluency and thoughtfulness that we don't often see."