Ghibli Gods: The 5 Most Powerful Characters In Miyazaki Movies Ranked

Long before A24 or Neon demonstrated the pop cultural influence that can be held by a single studio, Studio Ghibli was in a class of its own. Indeed, Ghibli films share a sharper through line than perhaps any other studio's body of work, with its entire output defined by morally ambiguous scripts and a principled admiration of the pencil over digitalization.

No filmmaker is as synonymous with Studio Ghibli as Hayao Miyazaki, who co-founded the animation studio in 1985 alongside Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki. Miyazaki has created countless classics, and his films "My Neighbor Totoro" and "Spirited Away" are the only animated entries in Sight & Sound's most recent decennial list of the 100 greatest films of all time.

Miyazaki is a master craftsman when it comes to all things fantastical, and his characters frequently harness powerful abilities of otherworldly proportions. There's a case to be made that the most powerful entities in Miyazaki's films aren't characters at all, in fact. In some films, it's the overwhelming, uncaring force of nature, expressed both fantastically and historically (think, for example, of the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, as ferociously depicted in "The Wind Rises"). Elsewhere, it's the sinister specter of war, as seen most recently in the best animated film of 2023, "The Boy and the Heron."

Miyazaki's most powerful creatures aren't inherently good or evil, and it's that gray area that makes them all the more compelling — and devilishly difficult to rank. "I'm not a god who decides on what is good and bad," Miyazaki told the New York Times. "We as humans make mistakes."

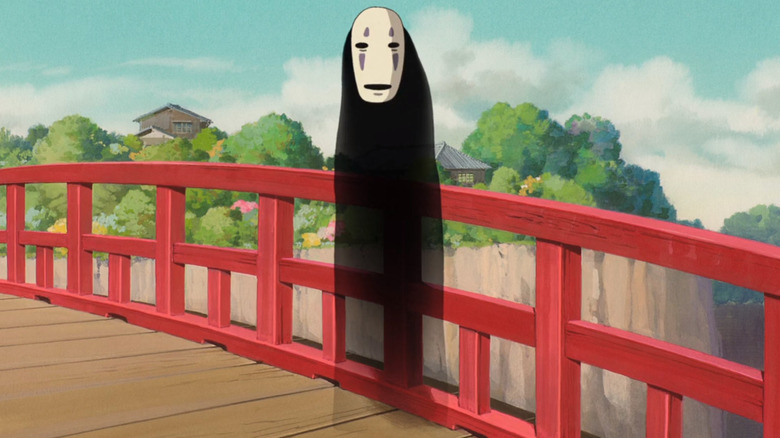

No-Face (Spirited Away)

2001's "Spirited Away" is saturated with colorful characters. That's to be expected in a film that takes place in an interdimensional bathhouse for spirits, the denizens of which include miserly frogs, anthropomorphized radishes, and hard-working soot sprites. For the story's protagonist, Chihiro, the world of "Spirited Away" is as much a spa as it is purgatory. When her parents greedily nosh on food meant for spirits, they turn into pigs, and young Chihiro must find a way to save her porcine parents and return to the human world while working at a bathhouse populated by otherworldly characters.

A novice employee, Chihiro invites the enigmatic No-Face inside, assuming he is a customer. As his name suggests, No-Face is a blank slate. He is mild-mannered, silent (save his cooing "ah" sounds), and, above all, lonely. In the spa, however, he becomes a manifestation of the establishment's worst qualities, and his loneliness is a vacuum. No-Face is consumed by the insatiable greed that runs rampant in the bathhouse. Soon he begins gobbling up gold, material possessions, and even other customers.

No-Face's greatest power — and the source of his undoing — is that he is a mirror to his environment's greatest ills. He may not be outwardly evil like some Miyazaki inventions, but he represents a very human capacity for greed and, in some instances, terror. As Miyazaki pointedly said, "No-Face is inside all of us" (via Otaku USA Magazine). No-Face only relents when he achieves what he wanted all along: companionship.

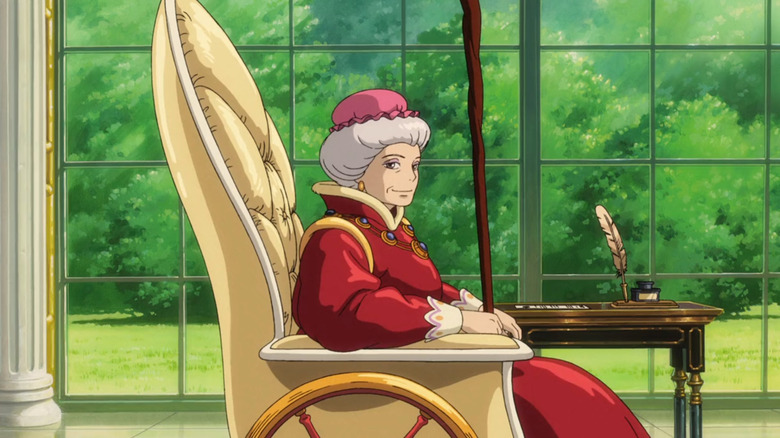

Suliman (Howl's Moving Castle)

Much of Hayao Miyazaki's filmography is defined by his intense pacifism, but "Howl's Moving Castle" was the filmmaker's most explicitly anti-war film to date when it was released in 2004. Set in a steampunk kingdom where magic and modern technology intersect, the animated adventure follows the story of Sophie, a young woman turned elderly by a wicked witch. In an effort to undo this curse, Sophie takes up residence in the titular castle belonging to Howl, a powerful wizard. At the same time, a war rages on between Sophie's kingdom and a neighboring one, and Howl's efforts to interfere in the bloodshed become increasingly dire.

"Howl's Moving Castle" is largely concerned with power — who is allowed to wield it and what they must surrender in the process. Howl is a skilled wizard who possesses the ability to fly and transform into a bird, but much of his power comes from Calcifer, the fire demon, who acts as the creaking castle's engine.

The most powerful character in the film is Madame Suliman, the King's chief sorceress. Even though she looks like a sweet old woman, her mighty strength has even Howl quaking in his boots, and she's able to strip the Witch of the Waste's powers without even getting out of her chair. The enormity of Suliman's powers is evident at the end of the film, when she decides on a whim to end the war, all while in the safety of her magnificent greenhouse in the King's castle. It's a potent statement from Miyazaki that the fate of thousands is often determined by a faceless and capricious few.

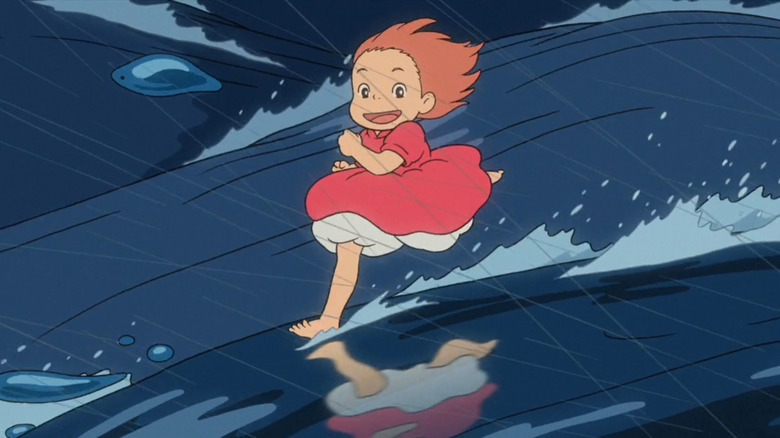

Ponyo (Ponyo)

Absolute power from some authority on high is terrifying, but what if it's in the hands of a child? How about a child-fish hybrid? When "Ponyo" was released in 2008, it was arguably Miyazaki's most child-friendly film to date — not just in the playful subject matter, but in the simple and bright visual design. When a goldfish princess explores the world above the waves, she longs to join the human world. In that pursuit, the princess — dubbed Ponyo by the boy who finds her — accidentally unleashes her wizard father's arsenal of magic, resulting in a dangerous imbalance in nature.

That imbalance causes a dangerous tsunami, but Ponyo is too overjoyed to register its danger. Indeed, Ponyo is among Miyazaki's most naive characters, making the power she harnesses all the more terrifying. While Sōsuke and his mother struggle to weather the storm, Ponyo happily skips among the waves. Later, she turns Sōsuke's toy boat into a real one, but it once again becomes miniature when she falls asleep, exposing the children to dangerous flood waters. Ponyo is by no means malicious, but watching her possess magnitudes of power she doesn't understand adds a thrilling tension to the film.

The God Warriors (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind)

For his second feature film, 1984's "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind," Hayao Miyazaki tackled weighty subjects like war, disease, and ecocide. As such, the film contains some of the filmmaker's most arresting and unsettling imagery, including toxic, waxen-looking plantlife and giant Ohms that scuttle across the desert. The film's most terrifying creatures are the ancient and omnipotent God Warriors, who, we learn during the opening credits, destroyed most of the planet one thousand years prior during the Seven Days of Fire.

The God Warriors are biblical in scope, recalling the fiery wrath of Armageddon, and their relative anonymity makes them all the more terrifying. We never learn how they came into existence or what purpose they serve other than total destruction. Their mammoth, petrified bodies continue to dot the landscape as a reminder of their past horrors.

"Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" is full of acts of human hubris, perhaps none so ill-advised as the plot to regrow a God Warrior embryo into an unstoppable bioweapon. Its pulsating tangle of muscles and veins is disturbing to witness, and it is easy to see the influence the monster had on later anime like "Neon Genesis Evangelion" and "Attack on Titan." The ploy is, thankfully, unsuccessful, and in a horrific body horror sequence, the final God Warrior melts into a bloody pile.

The Forest Spirit (Princess Mononoke)

It had to be him, didn't it? If Miyazaki's filmography captures the gray area between good and evil, then perhaps no film encapsulates that balance more than "Princess Mononoke," which the New York Times' Janet Maslin described as containing "an elaborate moral universe." An environmentalist fable, "Princess Mononoke" follows the mounting imbalance between the gods of the forest and the humans who work to preserve the survival of mankind, even if it means ravaging the forest's resources.

At the center of the tale is the deer-like Forest Spirit, who inspires awe in all who look upon him. The Forest Spirit is a master of life and death, causing vegetation to either crumble or bloom at his feet. At night, he transforms into a towering Night Walker with wobbly blue horns that extend skyward.

In a misguided effort to save Iron Town from invading samurai, the town's leader, Lady Eboshi, beheads the Forest Spirit. To use the Philadelphian proverb, she f***ed around and found out, as the headless spirit soon wreaks havoc over the land, transforming into a vengeful Night Walker and emitting a destructive ooze. In death, the Forest Spirit becomes Miyazaki's most powerful invention yet.