Movies That Made Us Cry In The First 15 Minutes

There's nothing like a good cry, and nothing like a good cry from an excellent movie. We know how Titanic ends and yet we watch it again and again, reliving all the opulence and romance of the first half that we know is doomed to a watery grave. We lap up Romeo and Juliet as much for the beauty of its language as for its tragic third-act collapse. We praise movies as "tear-jerking" and "heart-wrenching." The Greeks had it right, thousands of years ago: catharsis is one of the highest aims of art, and one that we will never stop chasing.

But what of the movies that deliver a sucker punch of sadness right off the bat? Perhaps this is done to prepare the viewer for darkness ahead, to raise the stakes, to contrast against later joy and ease. For whatever reason, it's a gutsy move to maroon the audience in a sea of sorrow 15 minutes in, and it often leads to some truly innovative cinema. We've assembled 11 examples of movies that do just that for all manner of reasons. Examine, peruse, and seek these films out — just don't forget your tissues.

Kids

Kids engendered a firestorm of controversy so enormous that, even two decades after its debut, it's still infamous. An unsparing (if a bit sensationalized) look at the youth of 1990s America, Kids is all about hedonism, substance abuse, and unsupervised debauchery among children whose greatest concerns should be homework and cartoons.

From the very beginning, it is unrelentingly cynical. We open on Telly, a snot-nosed teen boy whose biggest interest is deflowering virginal girls. His first act, in fact, is to do just that with an unnamed 12-year-old. Telly then meets up with best friend Casper, toting a brown-bagged bottle of booze, and they roundly abuse the women and girls they coerce into unsafe sex. It's a brutal look at vulnerable children being twisted into acts they can't comprehend the magnitude of, the sowing of seeds they'll be reaping for years. As an adult, you know this — and perhaps have foreknowledge of the movie's lurid reputation. But the kids are just that, and think all they're doing is having fun. Only you, in the audience, understand how dearly they'll pay for even the first things they do.

The Fault in Our Stars

The Fault in Our Stars begins with protagonist Hazel telling the audience that the following story will not be the gauzy romantic fable they might be hoping for. "This is the truth," she says, staring down the viewer. "Sorry." As the movie plunges into the realities of her life, one realizes she was not exaggerating for the sake of teen jadedness. Hazel has thyroid cancer that has spread to her lungs and her mother is urging her to attend a support group despite deep skepticism.

Though she does find fellowship there, the movie is utterly unsparing in its depiction of Hazel's life from scene one. She is physically impacted, and has no idea how much further her illness might impair her. The structures put in place to ease her loneliness are often unhelpful, and strike her as saccharine. Even if one finds friends, the humor is black as coffee and there are no qualms in discussing death, dying, and sickness. Though the film does find joy in the romance Hazel goes on to find with Augustus Waters, it is set against a backdrop that is often bleak and sometimes borderline cruel. At least Hazel prepares you for it.

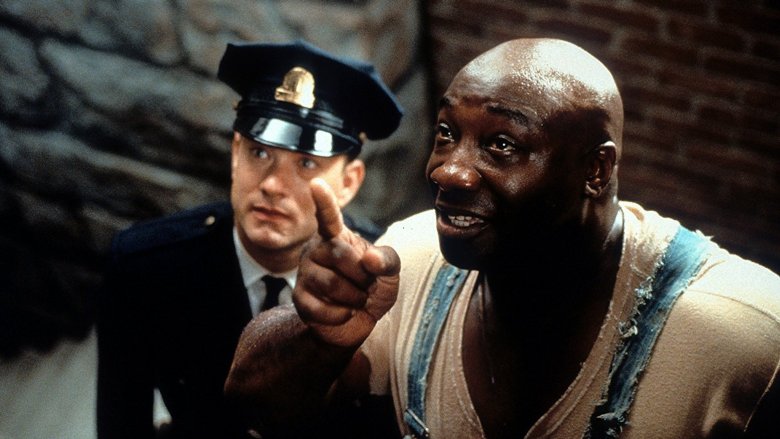

The Green Mile

Paul Edgecomb's life has grown very small when we enter into it. His world is a nursing home in which he's taken care of, but is left to his private preoccupations and prone to fits of inarticulate tears at 1930s movies on television. There is a helplessness to him that is hard to watch, even before we learn what is weighing on him, a grief he carries with every step. We go on to learn that he worked in a prison, and briefly cared for a prisoner named John Coffey, who displayed supernatural, borderline-religious powers.

Coffey is a kind man, one with an uncomplicated love for humanity — but it's the 1930s and he is black, and the state believes he defiled and murdered two young white girls. We learn that this isn't true, but it's via his abilities — what can he prove? And so Paul Edgecomb puts him to death, and pays for it in ways he couldn't have foreseen. Did he kill the second coming of Christ? Was he responsible for snuffing out an uncorrupted light? Perhaps. And that is how he came to be the old man in the beginning of the movie, left to himself and his demons, shuffling after something like redemption without any hope of a fellow traveler.

Saving Private Ryan

The first half-hour or so of Steven Spielberg's World War II masterpiece has become renowned as a complete work of art unto itself. A depiction of the storming of Omaha Beach, it is simultaneously gritty and vague, a pitch-perfect rendition of the fog of war that parts, every few minutes, to reveal fresh horror. So great is its infamy that one cannot watch it without knowing what they're in for — and yet still, the sequence leaves one shaking.

We see men who have become storied warriors in our modern culture, reduced to desperate tears as they wrestle with injuries that will kill them, hundreds of miles away from all they know and love. We see soldiers forced to choose between personal allegiance and the greater mission at hand in the midst of explosion and gunfire. We see terrible loss and incredible bravery, and the intertwining of it that made D-Day the landmark moment in history it was. Spielberg spares no detail, emotional or physical. His greatest tribute to these men is to document their suffering and courage with unflinching honesty. After fifteen minutes, you won't just be crying — you'll be changed.

The Lovely Bones

The Lovely Bones takes no pains to hide its premise. You go into the movie knowing it's about a young girl who was murdered, and that she spends almost all of the story trapped in heaven, watching her parents try to build something from the wreckage of their lives. But that doesn't make the opening chunk of the movie any easier to take. There is, of course, Susie's murder itself, though it's thankfully left vague in the details. We see her lured by her neighbor into the warren he's dug in a winter cornfield, and we see her swallow her discomfort in an effort to be a well-mannered young girl. We see him lie, telling her that he built it as a clubhouse for the neighborhood kids. We know what's going to happen to her, and it is excruciating to sit through.

Yet before that, even, there are scenes of Susie's life — brief, and interrupted by her narration which informs you that she is about to murdered and that her family was in no way prepared — bright and happy and utterly untroubled. She thinks her parents' limit on how many rolls of film they'll buy her at one time is the cruelest thing she'll ever suffer. She's dying for handsome Ray Singh to notice her. She didn't really understand the screening of Othello in her English class. And because of what we know is coming, it's just as shattering to behold as what cuts it all short.

Requiem for a Dream

The screen lights up with infomercials at the start of Requiem for a Dream: a manufactured vision of happiness out of reach, yet eternally tantalizing. Darren Aronofsky's intense vision of desperation and drugs goes on to spend its entire runtime examining just what lengths people will go to for this vision — and what depths to which they will sink. But first, we open on a crowd full of chanting people and the warring mother and son in front of the screen.

The son, Harry, berates her, and the mother, Sara, placates him. He takes her TV. The score soars ominously, and Harry and his friend are off and running, thinking their business in heroin is going to help them reach their dreams. Yet everything about the first fifteen minutes of the film tells the audience otherwise. Their lives are too small, too squalid, and too bound up in crime to ever amount to much of anything. They'll always be sitting in front of the TV, watching other people achieve success. And even that is fake.

Remember Me

Remember Me is a romance, taken up with largely positive emotions of togetherness, hope, and joy. Yet it begins in absolute terror when protagonist Ally and her mother are mugged in 1991 New York City, and the latter is ultimately shot. This trauma, and others like it, haunt the main characters as they sail through time, careers, schooling, and ultimately, love.

Remember Me proved controversial for its ending twist — the male lead dies in the 9/11 attacks in a move many critics found maudlin at best and exploitative at worst — but before any of that, it's a meditation on memories. They can be luminously beautiful and carry one through the worst times, but they can also be as traumatic and damning as Ally's experience in the opening of the film, which chases her throughout her life. It's not just that her mugging and her mother's murder was a horrible act, it's that it isn't confined to just that one part of her life. She has to find a way to escape its shadow — or live within it and find hope in her endurance.

Room

Room is a movie defined by loss. Told by five-year-old Jack, it tells the story of his home (the titular room) and his eventual escape from it. The audience understands from the beginning that the room is not the wonderland Jack imagines it to be, but a prison his kidnapped mother has been trapped in since she was a teenage girl snatched off the street. Room is where TV is, and Wardrobe, and Rug, and all the other things his mother (a wrenching Brie Larson in an Oscar-winning performance) has personified for him to bring joy to their dour existence.

Ultimately, Jack and his mother escape, and the second half of the movie is consumed with the media frenzy that surrounds them, their path towards healing, and the complexities of trauma — but before any of that, Room is about how much Jack can't even comprehend what he has lost, living his life thus far in a soundproofed shed. The audience is introduced to the toy snake made of eggshells that lives under the bed, to his treasured time with Dora the Explorer, and the few minutes a day he and his mother spend screaming as loud as they can towards the heavily bolted skylight for no reason he can understand beyond fun. Jack is so proud of the rhythms of his life, his knowledge of the world, his relationship with his mother. But to the audience, the first few scenes of Room are a lesson in everything that can be taken from a person.

Melancholia

Melancholia contrasts Justine, a newlywed whose depression has plunged her into an emotional abyss no light can penetrate, against the apocalypse. Melancholia, a rogue planet, has appeared and is on a sudden collision course with Earth — a collision that ends the film but also begins it, as one shot of many in a sequence set to the soaring strings of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. The sequence is enormously unsettling and deeply mournful in a way all the more potent for how strange it is.

We watch Justine, beautiful in her bridal gown, floating in a river, famous paintings burning, and a horse collapsing to the ground. Finally, we watch Melancholia slam into the planet we occupy, destroying everything. The story in earnest then begins, introducing characters we know now have but days to live. Melancholia isn't just a story about something terrible, but about feeling something terrible — and it absolutely drenches its audience in despair to achieve its aims.

Star Trek

You might think you're ready for the opening scene of Star Trek. It establishes itself on the USS Kelvin, featuring one George Kirk. Alright, you might say to yourself, this isn't the Enterprise and that Kirk isn't James — he's toast. You'd be right and terribly wrong. As George Kirk is killed in a cosmic conflagration, you will be made to care.

In a rush of an introductory sequence, we behold Romulans, a change of captaincy, and George's sacrifice as he uses the ship to ram the Romulan-piloted Nerada. His last communication, conducted right up until the moment of impact, is with his wife, who goes into the labor that will produce the Captain James T. Kirk we know and love. But the movie never feels overstuffed — just honest to the pile-up of emotion and action that happens in any emergency. George is calm in the face of death, every inch the brave leader his crew needs in that moment, ready to die for the good of a larger whole. But as he hears the birth of his son over the communicator, and as he knows he'll never meet him, there's a flicker of something like regret in his eyes. It's a heart-rending story — and it's over within fifteen minutes.

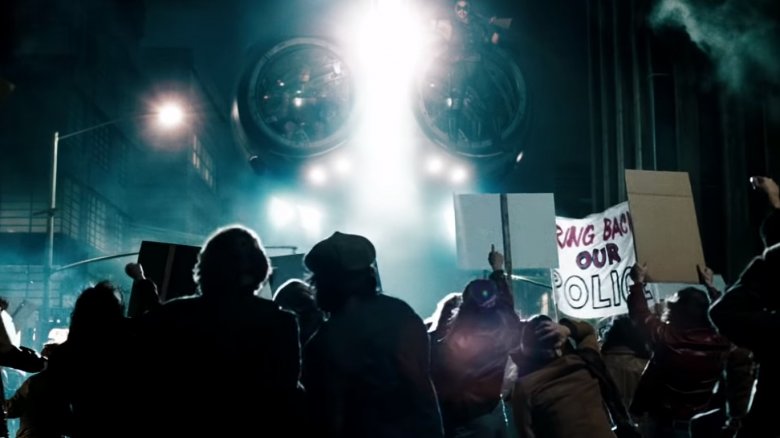

Watchmen

Watchmen's opening montage is its own story of the heroic Minutemen, the golden age of this world's superheroics, and how it all came crashing down. We see icons like Silk Spectre and Nite Owl grin for the camera, we watch the Silhouette kiss a nurse on V-J Day, we see the Comedian deliver a hook into the jaw of a gun-toting burglar. Then we see the Silk Spectre's marriage descend into chaos. We watch Nixon elected to a fourth term. We see the Silhouette murdered in bed beside the nurse, a homophobic slur written in blood above their bed. It's shot in extreme slow motion and colors that blur and fade but never quite lose their vibrance, all set to Bob Dylan's plaintive "The Times They Are A-Changin'." Even as its optimism becomes more and more degraded, it never quite stops being a beautiful sequence.

This makes it all that much worse as shots of bombers over the Kremlin and Molotov cocktails thrown at storefronts light up the screen. Times have never been worse, but it's just so easy to get lost in the splendor of it all. Watchmen remains controversial among superhero fans, but no one can deny how eerie and downright discomfiting its opening is — and how utterly perfect that is for the property.