Things Movies Always Get Wrong About Lawyers

Hollywood loves stories about lawyers. The legal profession allows for plenty of drama, moral debates, and climatic courtroom scenes that audiences love to witness time and time again. From Atticus Finch's impassioned speech in To Kill A Mockingbird to the shocking revelations at the end of A Few Good Men, movie lawyers continue to fascinate audiences with tales of moral imperatives and underdogs defeating their well-funded, often morally dubious opponents.

The life of a lawyer may appear glamorous and exciting on screen, but the stark reality is a little less... dynamic. While the focus of many films tends to be on scintillating speeches about justice or intense cross examinations that end in an exonerating confession, this only represents a small portion of what lawyers do as they work on a case.

Not seeing the whole picture of the world of law isn't the only problem Hollywood has with attorneys. Whether it's the rules of legal proceedings being bent or the less thrilling aspects of the profession being cut for time and excitement's sake, there are more than a few things that filmmakers tend to get wrong about the legal profession.

The legal profession rakes in money

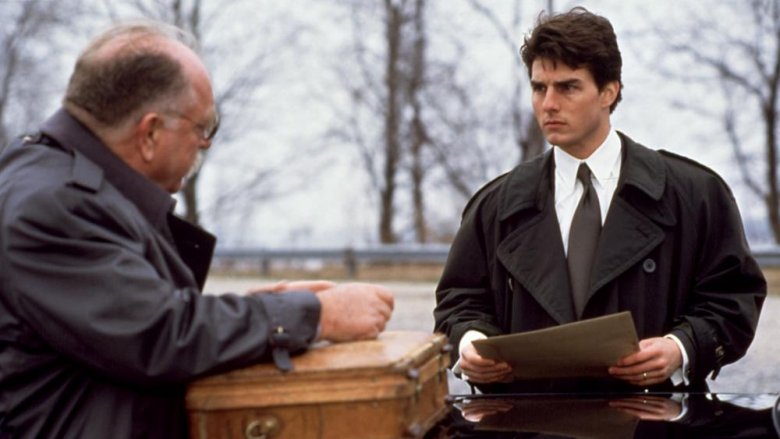

In Hollywood, being a lawyer is generally seen as a lucrative profession. In the thriller The Firm, Mitch McDeere, a young lawyer played by Tom Cruise, joins a prestigious law firm. Shortly after being brought into the firm, McDeere is given a six-figure salary and a Mercedes, all as a part of his initial employment contract.

The L.A. Times interviewed lawyers regarding The Firm's portrayal of their profession and McDeere's benefits. Sheldon Fleming, a lawyer from the firm Walsworth, Franklin and Bevins criticized the film, asserting, "There's no first-year associate around that is worth $90,000."

According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, the median salary for lawyers is $141,890. While this is certainly enough for an individual to live comfortably, the amount does not reflect the millions lawyers seem to rake in on screen. Additionally, according to the National Association for Law Placement, public defenders' median salary is significantly less, at $58,300.

So while, in reality, lawyers do make a lot of money — especially if they work for a private firm — films have a tendency to embellish and glamorize the lifestyles of lawyers in general.

Good lawyers work for good people

Narratively, it makes sense that good lawyers work for good clients. Characters like Atticus Finch from To Kill A Mockingbird exemplify this ideal and reinforce the notion of heroes aligning themselves with sympathetic underdogs. Audiences generally want to cheer for the good guys, and having a lawyer on the morally correct side of justice is both convenient and narratively rewarding in the eyes of filmgoers.

By that same token, it is always more fun for audiences to root against people they dislike, leading to many lawyers being framed in the same way as the antagonists they represent. For courtroom dramas, it is not uncommon to make opposing lawyers pompous, arrogant, and duplicitous for the sake of making their inevitable defeat all the more emotionally satisfying.

In reality, this is not always the case. Lawyers take on strong cases they can win. The Sixth Amendment guarantees Americans the right to legal representation. This means that everyone, no matter how morally questionable, deserves a lawyer on their side. With this in mind, it is inevitable that even a good lawyer may have to serve a guilty or otherwise unethical client.

Lawyers are all scummy

In many films, lawyers are the villains simply because they represent the film's antagonist. For many viewers, there is a perception that evil lawyers represent evil people. This is evident in films like The Godfather, in which the Corleone family is often able to avoid legal trouble with the help of their lawyer, Tom Hagan.

In reality, this is not necessarily the case. Altruism is an important value among lawyers — just look at the concept of pro bono representation. Pro bono is simply voluntary work that lawyers take on for the public good, taking a case at a reduced cost or for free.

According to the American Bar Association, lawyers have a professional responsibility to provide at least 50 hours of pro bono services per year. Unlike most of their film counterparts, for actual lawyers there is an expectation that they serve the public and act outside of their own personal interests.

No clerks, staffs, or researchers

Most courtroom dramas focus on the work of a single lawyer who is instrumental in solving their particular case. The climax virtually always occurs in the courtroom during the trial, but this focus all but erases the work of legal aides, researchers, and everyone else who works in law offices to assist lawyers in their casework.

Considering the amount of research and organization required in court, a lawyer's job would be nearly impossible without some extra help. In large law firms, lawyers often rely on teams of clerks, paralegals, secretaries, and even investigators to make strong cases for their clients.

For example, many lawyers rely on paralegals for their general knowledge of the legal system and the law in order to get certain basic tasks done, thus freeing them up to attend to more pressing matters. Sometimes, a law firm will hire an independent lawyer if a case requires more specialized knowledge.

When all of the workers at a law firm work together effectively, it lets the lawyers handling cases focus on all of the work that is typically shown on screen. Even though this is a problem of omission, it still stands that other members of legal teams are virtually invisible in their big-screen depictions.

Only have one case at a time

Films that revolve around trials almost always focus on one specific case. For the lawyers in these films, this particular case is usually framed as the sole focus of their work, engulfing every aspect of their life. While some cases do require a significant amount of attention due to their scope, many lawyers take on multiple cases at once and have to divide their attention between them.

According to a study of the U.S. court system by the International Academy of Trial Lawyers, some courts can take up to five years to start proceedings due to how backed up the courts are with old cases that have yet to be tried. As a result, most lawyers cannot wait that long to get paid if they are only working on one case. They have to work on several cases at once to keep a stable flow of income.

Public defenders in particular are known for taking on exceedingly heavy workloads. One public defender, Jack Talaska, was cited by the New York Times was working on 194 active cases at one time, something that would have required him to do the work of five full-time lawyers if he were to give each case the time it needed for an optimal defense. When describing the work of a public defender, Talaska stated, "Most offices don't have paralegals, law clerks, or full-time investigators."

Lawyers can do whatever they want when a witness is on the stand

Courtroom scenes are often tense affairs on film. And one of the most tense moments of any courtroom scene is when a lawyer gets the chance to interrogate a key witness on the stand. A lot of the time, this culminates in a dramatic confession, a la A Few Good Men or ...And Justice for All.

However, sometimes filmmakers opt to portray court proceedings in a more... elevated fashion. When the trappings of more realistic court cases aren't enough for the dramatic tension of a given scene, some portrayals bend the rules and regulations that govern courtrooms everywhere.

Take The Dark Knight. In it, Harvey Dent shows up in court where a witness on the stand pulls out a handgun and tries to shoot Dent. However, the gun has no ammunition loaded, so Dent punches the witness in the face and takes the gun from him while bailiffs subdue the suspect for detainment.

In yet another physical confrontation, Intolerable Cruelty showcases a scene where a lawyer lunges at a witness on the stand and begins to throttle them, an action allowed by the judge after objections from the opposing side. According to Southern University's online guide for courtroom conduct and etiquette, witnesses must be respected in the courtroom. That typically means refraining from physical confrontations.

Court cases happen quickly

Many films that center around a legal battle often have cases that are decided mere minutes after the end of arguments made in front of a judge or jury. However, the timeframe for obtaining legal decisions is rarely so concise in the real world.

According to a study conducted by the International Academy of Trial Lawyers examining the circuit court of Cook County, Illinois (the largest urban court in the United States), "The average time in Cook County for a case to be disposed of by settlement, dismissal for want of prosecution, default, or verdict is 35.3 months and the average time from the filing of the lawsuit to verdict is 51.9 months."

Most films do not properly represent just how long the process of taking someone to court really is. This could be to tighten the narrative tension, or it might happen because simulating the characters' years of advancing age would be costly and confusing to viewers. Regardless of the choices any given movie makes about its timeframe, the fact remains that climactic decisions from judges and juries don't happen overnight.

Outbursts in the courtroom

Trials are serious affairs, and proper conduct in the courtroom is an incredibly important standard that lawyers are obligated to meet. Going back to South University's guide to courtroom etiquette, "The judge not only represents the ultimate authority in the court, but also the law." Naturally, this means that outbursts can result in disaster for any lawyer, witness, or party being represented. But some things slip through the cracks when courtroom scenes are put to the screen.

According to the United States Department of Justice, contempt of court can simply be defined as a show of disobedience or disrespect towards a judge or other officers of the court. One of the most egregious examples of cinematic court misconduct is found in Liar Liar, starring Jim Carey as Fletcher Reede. After winning a case for his unethical client, a regretful Reede shouts at the judge, demanding that he overturns the sentence. This outburst results in Reede being held in contempt of court.

Arguably the most famous courtroom outburst is from the classic Marine court-martial drama A Few Good Men, wherein Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise) is questioning Colonel Nathan Jessup (Jack Nicholson). After a fair amount of yelling back and forth, Jack Nicholson barks, "You can't handle the truth!" Despite making that exclamation famous, a more realistic courtroom scene would likely be more polite, composed, and less loud for fear of being held in contempt of court.

Preparing for trial

As was showcased in the study from the International Academy of Trial Lawyers, it is not uncommon for cases to take years in major cities. That means that lawyers have a lot of time to prepare before each case progresses to the next stage along the legal track.

Preparing for a case is a huge undertaking. In order to properly represent their clients, lawyers have to spend countless hours and resources readying a defense. If a lawyer walks into a courtroom unprepared, they will likely lose the case. In the L.A. Times interview regarding The Firm, Paul Hastings associate Jon Meer stated that preparation isn't exactly glamorous work. "If they made [The Firm] realistic, it would be people sitting around in a library," he said, "and nobody would want to watch it."

Audiences don't want to watch characters sitting around reading thick files and dense law books — they want action. As a result, films typically skip all of the legal legwork and jump straight into the trial.

Objections

Many professions have some variety of jargon that everyone knows, but that doesn't mean everyone knows what those words or phrases actually mean or how to use them correctly. For doctors, this might be ordering, "I need a nurse here, stat!" For lawyers, this comes in the form of exclamations like "Objection!"

An example of this can be seen in Kaffee's interrogation of Jessup at the climax of A Few Good Men. Cruise asks, "Colonel, Lt. Kendrick ordered the code red, didn't he? Because that's what you told Lt. Kendrick to do." Jessup's lawyers shout "Object!" without specifying the reason for the objection. The judge sustains the objection and threatens Cruise with a contempt charge as he continues his line of questioning.

Cornell Law School defines an objection as a formal protest raised during trial that suggests the judge disallow testimony or evidence that is in conflict with court proceedings.

Usually, an attorney would need to elaborate on the objection. According to The Legal Seagull, a law blog run by a Los Angeles-based business lawyer, an objection based on argumentative questioning is used to combat questions which "attempt to influence the witness' testimony by inserting the attorney's interpretation of the evidence into the question." And since Kaffee is inserting his theory of events that are not directly supported by the evidence of the case, this would have likely been a good explanation for Jessup's lawyers to give to the judge.