The Greatest Horror Movie Endings Of All Time

Finding a scary idea that could form the beginning of a horror film isn't always the hard part. Lots of things scare us, and lots of those things can be translated into a visual medium in such a way that we'll be hooked after just a few minutes. What makes a truly great horror film is often its ending, and far too many movies in the genre fail to stick the landing.

What's a good horror ending? It's scary, sure, but it can also be funny, emotionally wrought, and so mysterious that it raises more questions than it answers. Put simply, the best horror film endings are the ones that stay with you long after you've left the theater.

To celebrate great horror movie endings, we've put together this list of some of the greatest horror film conclusions of all time, from intense final scares to intriguing head-scratchers to clear, bloody resolutions.

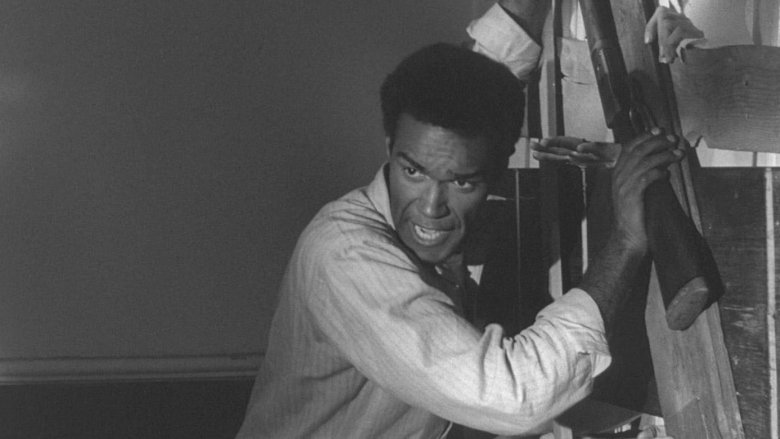

Night of the Living Dead

Night of the Living Dead remains revolutionary for a number of reasons. Director George A. Romero's 1968 film created the modern zombie genre as we now know it, reshaped our expectations for horror cinema, and added a layer of social commentary that was helped along by the presence of Duane Jones, a black leading actor at a time when that was nearly unheard of, as Ben.

Ben spends much of the film arguing with other white characters about the best course of action to take, and then manages to emerge as the sole survivor of the battle at the farmhouse overnight. With the sun rising at last, he hears an approaching rescue crew and stumbles to the window to catch their attention... only to be immediately shot in the head and thrown onto a pile of burning corpses like just another ghoul. It's a shocking twist in the midst of what's supposed to be a calm resolution — something many brilliant horror films would take a cue from in the decades that followed.

It's also a bold statement on the way black men were (and are) being treated in America. For all his will and for all his prodigious survival instincts, Ben was dismissed by people who were supposed to be his saviors, and became another casualty of a society eating its own. The closing credits featuring the body disposal only make everything that much more stomach-turning.

Rosemary's Baby

So much of Rosemary's Baby takes the form of a paranoia-driven thriller that, from a certain perspective, you could almost frame it as the story of a pregnant woman (Mia Farrow) who has a strange dream one night and then grows increasingly terrified of the people around her. It could be that they're only trying to help, as some kind of hormonal imbalance or mental health issue drives her to think they're all out to get her. That's how much of the film plays, and it's easy to see how other filmmakers might have leaned into that even more.

But Roman Polanski's film all builds to that ending, in which Rosemary discovers that all of her paranoia has been engineered by a coven of Satanists, who arranged for the Devil himself to impregnate her, and that she has given birth to the Antichrist. The coven's calm celebration as they stand around the bassinet — not to mention the film's refusal to actually show us the child — only adds to the dread, which culminates in Rosemary accepting that she could indeed perhaps be a mother to this child.

The Wicker Man

The Wicker Man is a film that plays out in many ways like some kind of dream, because most of its characters seem to be living in an entirely different reality than the protagonist, Sgt. Howie (Edward Woodward). They dance and smile and walk dreamily through life as though nothing is wrong, despite the fact that Howie has come to investigate the alleged disappearance of one of their own children. As the film moves forward, we get the impression that he's about to shatter all of their illusions. Then, in the film's final minutes, they instead shatter his.

The ending of this film is easily and instantly compelling, thanks in part to the striking visual of the titular wicker man burning against the setting sun. It's a haunting image, one that works in the film's favor even now. What really makes the ending work, though, is Howie screaming out Bible verses as he's burning alive while the cultists around him sing their own song of Pagan celebration. It's not the ending you predict as Howie seems to get closer and closer to the truth. Even though he's a bit of a stick in the mud, you're still rooting for him to thwart the human sacrifices happening on the island. Then, as the wicker man burns, you're left feeling both horrified and spellbound.

Black Christmas

1974's Black Christmas is one of the most important precursors to the modern slasher film genre for a number of reasons. It's got the point-of-view cinematography, the slow ratcheting up of the body count, the holiday setting, the sorority house, and it even has the final girl in the form of Olivia Hussey's Jess.

Where the film departs from many other final girl narratives is in its haunting and horrifying closing scene, in which Jess is left alone to rest in her bedroom while police officers guard the house from outside. The camera then reveals that no one has bothered to check the attic, where two bodies and the real killer are still waiting for their moment, ensuring that Jess is still in terrible danger. The cheerful Christmas lights and snowy landscape juxtaposed with that persistent ringing phone as the credits begin to roll are among the most chill-inducing things in the history of slasher cinema. Without this ending, we might never have gotten the final moments of films like Halloween and Friday the 13th, both of which followed just a few years later.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Few films have ever captured a group of characters stuck in a situation as it descends into absolute madness quite like Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The film begins in a relatively quiet way, but once the true horror of Leatherface and his family kicks in it's absolutely relentless, taking us through meat hooks and butcher mallets and a dinner party from hell, all building to those final ecstatic moments in which Sally (Marilyn Burns) finally jumps into a truck to escape.

We're left with questions as Leatherface swings his chainsaw in the morning sun. Will he be caught? Will Sally ever be okay again? And perhaps most importantly: what would you do if you just saw a guy in a human skin mask slinging a chainsaw around in the middle of a country road? The chainsaw dance is the perfect little dose of madness to end this film for exactly that reason.

Jaws

They blow the shark up.

Jaws is often credited as the first summer blockbuster, a horror film with massive crossover appeal that became a legitimate phenomenon, launched Steven Spielberg's career into the stratosphere, and forever changed the movie landscape. Its ending, in which Brody (Roy Scheider) manages to finally defeat the killer shark after a brutal battle, is an over-the-top and thrilling resolution to a film that keeps viewers on the edge of their seats right up until the very last second.

Also, they blow the shark up.

It's just something we accept about the film now, but looking at Jaws in the context of its time, that was a bold and brilliant closing move. Spielberg's film moves with the constant taut pull of tension, and things are wound up so tightly by that final confrontation that it's difficult for audiences living in the moment of the movie to really imagine how it will actually snap. Then it all ends with a spectacular explosion, cementing the film's place as one of the great horror achievements of the 20th century.

Carrie

It's common practice in horror cinema to lull the viewer into a false sense of finality before unleashing an ending that suddenly and terrifyingly swerves for one last jump scare. It was done famously in Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street, as well as countless other formative films of the 1980s. But even before those films established that One Last Scare philosophy, there was Brian De Palma's Carrie, and its final moments.

When Sue Snell (Amy Irving) visits the site of Carrie White's burned-down home, we are immediately aware that something is off because of De Palma's dreamlike construction of the scene. Still, everything seems peaceful, concluded, and calm. Then that hand reaches up out of the Earth to grab Sue, and even though the film makes it clear that we are indeed watching a nightmare, the fear is still real. It's real because of the masterful way the sequence is directed, but also because after all we've seen Carrie do, coming back from the dead doesn't exactly seem so far-fetched.

The Shining

The Shining is a film so pregnant with symbolism, mystique, and meaning for fans nearly four decades after its release that entire documentaries have been devoted to decoding its many supposed hidden messages. It's so dense with possible interpretations, and nowhere is that clearer than its ending. When all the chaos at the Overlook Hotel has died down, the camera zooms in on a 60-year-old photo to reveal the smiling face of Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), and everyone leaves the theater or turns off the TV scratching their heads.

Is Jack a reincarnation of another man who came to the Overlook decades ago? Is he simply another version of the same spirit who keeps returning to this ground? Is the Overlook perpetuating a cycle of violence to sustain itself? Never has being so uncertain about a horror film's ending been quite so intellectually satisfying, and we've got nearly 40 years of theories, essays, and films to prove it.

Poltergeist

Poltergeist is one of those films that could have easily front-loaded all of its good ideas into the meaty scares for the first and second acts of the story, leaving the finale a little too predictable and a little too stiff. After all, the scene of young Carol Ann (Heather O'Rourke) ominously announcing the arrival of spectral visitors through the TV is iconic in itself, and many ghost movies might have just coasted on that one striking image. Thankfully for all of us, that's not what Poltergeist does.

We can talk about the clown doll, the pool full of bodies, the creatures from beyond, and everything else that comes up during the final confrontation in the film, but what really makes it all work is the house's eventual collapse into an extradimensional ball of debris. In that moment, Poltergeist goes from instant classic to eternal classic, the kind of film we'll talk about forever. Then, to add even more brilliance to the crazy finale, we get that TV getting pushed out to the hotel patio. Some horror films leave you with one last scare, but this film leaves you with one last laugh as the whole audience nods in agreement.

Phenomena

When it comes to the endings engineered by horror master Dario Argento, films like Deep Red and Suspiria often get most of the attention, but no one should sleep on Phenomena. It begins as a relatively straightforward supernatural thriller about a murderer on the loose and a young girl (Jennifer Connelly) who may be able to find the killer through her strange ability to communicate with insects. Then, in the final minutes, it just gets bonkers.

Jennifer, on the run from the killer, is sheltered in a house by the suspicious Frau Bruckner (Daria Nicolodi), who turns out to be in on the murders. What follows is a thrilling and terrifying gauntlet of horrors that includes a pit of decaying corpses, a horribly deformed child who's eaten alive by flies and then burned to death, a decapitation with a sheet of metal, and then the final twist: Frau Bruckner, on the verge of killing Jennifer, is murdered instead by a friendly chimp who comes to the rescue with a razor. Yes, this movie ends with a chimpanzee taking revenge and murdering a woman. It might not be the most stylish of Argento's endings, but it's easily his most unpredictable.

Bram Stoker's Dracula

Francis Ford Coppola's adaptation of Dracula was an attempt to bring Bram Stoker's original novel to the screen in a way that both utilized lush practical effects in a memorable way and also paid homage to the book's sexual themes and operatic sense of storytelling. The result is one of the most vivid horror films of the 1990s, and its ending is nothing short of beautiful.

After finally reclaiming his reincarnated bride in the form of Mina (Winona Ryder), Dracula (Gary Oldman) attempts to take her back home to Transylvania, only to ultimately be defeated. Instead of simply dispatching the monster, though, Coppola's film lingers on the love story, allowing things to culminate in a heartbreaking moment in which Mina sees the tragedy of Dracula as an eternal man longing for a reunion with the love of his life. Its final moments offer some consolation, as we see that Dracula and his bride seem to have finally reconnected in the afterlife after centuries apart.

Also Dracula's head gets cut off, which is pretty rad.

You're Next

Few home invasion horror films could ever hope to rise to the level of invention at work in You're Next. The movie just keeps piling on beautifully executed kills while also weaving in real emotional resonance and even quite a bit of humor to the proceedings. Then the twist — revealing that some of the family members are actually in on the masked killings — adds even more suspense to what becomes a brilliantly bloody final series of deaths. It could have all ended with that blender moment and the film would still be fantastic.

Then Adam Wingard's film pushes just a little bit deeper, as Erin (Sharni Vinson) learns that her boyfriend was also in on the deaths. A spontaneous killing, a fortuitous arrival by a police officer, and a call for backup all seem to point to Erin's eventual arrest, and then that axe falls. This film just keeps squeezing the audience until every last ounce of energy is out of us.

The Cabin in the Woods

The Cabin in the Woods is both a spoof of and a commentary on various horror movie tropes, but that commentary doesn't land unless the film is also able to deliver on the horror goods. You can't make a convincing meta-satire unless you've also got the real elements on which the satire is based, and it's there that The Cabin in the Woods really starts to excel.

This is particularly true of the film's climax, in which all of the horrors of the underground facility are unleashed at once. It's a wonderfully wicked way to both show us something scary and also make fun of horror movie expectations, but then the film goes a step further with the revelation that this is all a ritual designed to preserve humanity. The film's final moment, in which the surviving heroes decide to let the human race be destroyed, is both a subversion of what we expect to happen and a beautifully engineered final jolt of horror.

The Witch

For much of its runtime, The Witch seems to be the story of a devout religious family who begins to see hexes and demonic influences all around them when their baby is taken by a wolf. The isolation the Puritan family faces, plus their sense that everything they do is either God's will or the result of unclean behaviors, could naturally produce such a paranoid reaction to a tragedy. The Witch could have played the whole film that way, with no explicitly supernatural elements, and it still would have worked.

Instead, the film builds and builds to a climax in which Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) finally gives in to her curiosity and asks if Black Phillip, the goat, is really something more. What follows is a full-on Satanic embrace, complete with a witches' sabbath in the woods, and Thomasin's ecstatic rise as a young woman who's able to finally, fully be herself. It's a horror film ending that's both legitimately frightening and genuinely celebratory.

Hereditary

Hereditary is a film that's terrifying because of its focus on the nature of family tragedy and the horrific unpredictability of grief. But even if you just want to pull back from its emotional weight and just watch a creepy movie, it's also got you covered. The film's symbolism and tragic heft wouldn't work without the truly horrific sights its offers, and vice versa, and that all culminates in one of the most unforgettable horror endings of the 21st century so far.

The film just keeps building in its final minutes, piling freaky moment upon freaky moment until at last you're watching as nude cultists surround the house, smiling and waiting for what's to come. Then a headless corpse floats up into that treehouse, Peter (Nat Wolff) follows it, and the film's demonic payoff finally reaches a fever pitch. It's a dizzying display of terrors after the already harrowing moviegoing experience that came with the rest of the film's runtime.

Us

Jordan Peele's Us does not have the same tight, beautifully paced structure that made his debut feature Get Out so compelling, but what it lacks in storytelling elegance it makes up for with massive doses of ambition. What begins as a home invasion thriller about a family who's attacked by their own doppelgangers quickly escalates into something more, and by the film's final minutes we've been introduced to a dark plot to create a race of doppelgangers which then went horribly wrong.

That would have been enough to end the film in a satisfying way, as Adelaide (Lupita Nyong'o) dispatches her doppelganger in the tunnels before coming back up to join her family, but then things take yet another turn, as a flashback reveals that Adelaide was the doppelganger the whole time, and that she'd taken over the life of her original self when they were children. That, plus the brilliant wide shot revealing a grim imitation of "Hands Across America," puts the film over the top in a great way.