Movies That Had To Be Re-Edited After They Were Released

Most of the time, a film is shot, edited, and released theatrically, then that same film gets a home media release without any major alterations. That's not always the case, though. The history of cinema is full of fascinating stories in which films are, for one reason or another, re-edited even after they've been theatrically distributed in some form. Sometimes it's because of a disagreement between a director and a studio, sometimes it's because of censorship in a foreign country, and sometimes it's just because a filmmaker decided they wanted to tweak a few things. Whatever the case, whenever these recuts happen, cinephiles and casual moviegoers alike often take notice of how and why.

There are, of course, dozens of examples of this phenomenon, from simple DVD director's cuts to battles between filmmakers to entirely different versions of the same film released years apart. There are even cases of filmmakers going back to make changes after their films have won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Check out these fascinating stories of films that were re-edited even after they were released.

Star Wars

The original Star Wars trilogy is perhaps the most famous instance of re-edited work in cinema history, and that fame has now translated into more than two decades of infamy for the saga's creator, George Lucas. Though certain minor tweaks (including things like audio fixes) existed before that, the real infamy stems from Lucas' 1997 release of the Star Wars "Special Edition" cuts, which featured a number of new digital backgrounds and CGI creatures. Of course, they also spawned the now legendary argument that "Han Shot First" after Lucas altered the scene in which the smuggler kills the bounty hunter Greedo.

The long list of changes to Star Wars only multiplied with each release of the films, on DVD and then Blu-ray, as Lucas made still more tweaks that included things like Hayden Christensen as young Anakin Skywalker appearing as a Force ghost at the end of Return of the Jedi and Darth Vader yelling "Noooo!" as he kills his mentor, Emperor Palpatine. Fans continue to rage over these alterations, but according to Lucas, it's all just in service to getting the films to look and sound like he imagined them.

"On the Internet, all those same guys that are complaining I made a change are completely changing the movie," he said. "I'm saying: 'Fine. But my movie, with my name on it, that says I did it, needs to be the way I want it.'"

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Peter Jackson's adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy was famously recut into a series of extended editions upon DVD release, stretching the already epic runtime of each of the films into something even larger, with additional scenes that helped to flesh out Tolkien's world. The third installment, The Return of the King, is particularly noteworthy, as new material was shot after the film had already swept the Academy Awards and taken home the prize for Best Picture.

In the behind-the-scenes appendices for the film, Jackson revealed that three weeks after the Oscars ceremony in 2004, he and his crew returned to a New Zealand soundstage to shoot a few seconds of additional footage that was required for the extended cut. You can find the footage in the "Paths of the Dead" sequence, when Gimli looks down to see a series of skulls rolling into the dirt in front of him — an auspicious addition to a movie that had already claimed cinema's most prestigious honor.

Aladdin

Before it was remade in live-action, Aladdin was one of the most successful films in the "Disney Renaissance" that unfolded in the late 1980s and into the '90s. It's best remembered today for two things: Robin Williams' portrayal of the Genie, and the music. Composer Alan Menken won the Oscar for Best Original Score, and Menken and lyricist Howard Ashman (who died before the film's release) won Best Original Song for "A Whole New World." Not everyone was pleased with Aladdin's original songs, though, and that led to one key change in subsequent home media releases of the film.

The opening song, "Arabian Nights," originally featured the lines "Where they cut off your ear/If they don't like your face/It's barbaric, but hey, it's home." Arab-American Anti-Discrimination groups immediately demanded the line be changed because of its portrayal of Arabic people as violent barbarians. Disney, with the permission of Ashman's estate, ultimately agreed to change the lyric to "Where it's flat and immense/and the heat is intense/It's barbaric, but hey, it's home." Though anti-discrimination groups still complained about the use of the word "barbaric," that word remains in the film's soundtrack.

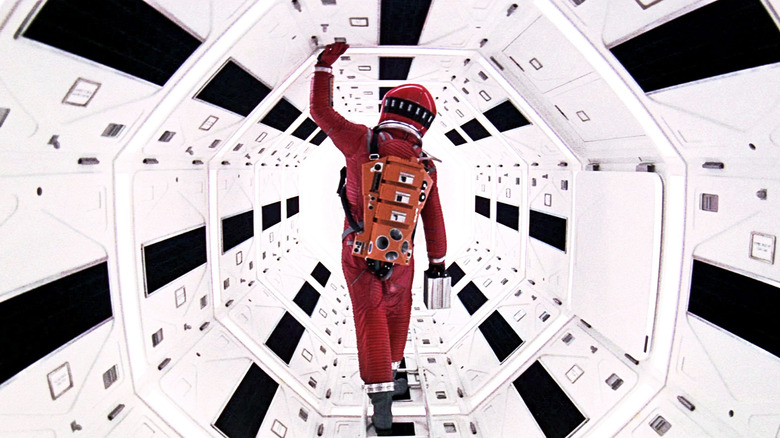

2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the great science fiction masterpieces in the history of cinema, still pored over and analyzed by everyone from diehard cinephiles to full-on philosophers five decades after its release. One thing the film has never been accused of being, though, is a fast-paced thrill ride. Kubrick realized this, but after its world premiere in April of 1968, even he was concerned that the film was making his audience a bit too "restless."

The restlessness of his audience was thanks in part to the age of the film's first audiences, which skewed a bit older than the young counterculture following it would later attain in wide release. Kubrick didn't foresee this, though, and made the decision to head back into the editing bay to cut nearly 20 minutes from the film for its wide release. Kubrick and his editor, Ray Lovejoy, trimmed the film together over four days of work, and instructions on how to cut the shipped prints of the film were sent to theater owners who already had their longer copies. This likely led to some discrepancies in what was actually cut, and the film may have varied from theater to theater. While the "lost" footage allegedly exists in the Warner Bros. vaults, it's unlikely to ever be seen, out of respect for Kubrick's wishes regarding deleted scenes from his films.

Brazil

Terry Gilliam's dystopian comedy Brazil is among the most remarkable science fiction films of the 1980s, not just because of the film itself, but because of the very public battle over its final cut. The film was released internationally by 20th Century Fox, who allowed Gilliam final cut control, but the same was not true of Universal Pictures, who was distributing the film in the United States. Studio head Sid Sheinberg deemed Gilliam's cut — in which the protagonist's vision of running away with the woman he loves is revealed to be an illusion — unreleasable, and assembled a team of editors to recut the film with a happier ending.

Gilliam, feeling any legal battle with Universal was a lost cause, made the resulting battle "personal" by taking out a full-page ad in Variety publicly asking Sheinberg, "When are you going to release my film Brazil?" As Sheinberg continued to lobby for his cut, dubbed the "Love Conquers All" cut by fans, Gilliam had begun secretly screening his own cut of the film for critics around Los Angeles. In December of 1985, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association named Brazil — Gilliam's cut of it, which hadn't even been released in the U.S. yet — the best picture of the year. That broke the gridlock, and Sheinberg agreed to release the film with Gilliam's ending.

Titanic

The Chinese government is well-known for censoring films from other countries before they can be shown to Chinese audiences. These edits happen for a wide variety of reasons, but one of the most amusing came in 2012, when the Chinese State Administration of Radio, Film and Television opted to alter one of the most famous scenes in James Cameron's Oscar-winning epic Titanic.

Titanic, of course, was originally released in 1997 to massive box office success and a record-tying award season run. The 2012 release was for Cameron's 3D conversion of the film, and the scene in question was the moment in which Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) draws Rose (Kate Winslet) as she poses au naturel for him. Why? Well, Chinese censors said that "considering the vivid 3D effects, we fear that viewers may reach out their hands for a touch and thus interrupt other people's viewing."

To hinder these attempts at fondling a 3D image from a movie released 15 years earlier, China showed the scene in question from the neck up.

Superman II

In 1979, Superman: The Movie director Richard Donner was fired from Superman II by the film's producers, and was replaced by director Richard Lester. What made this different from many productions in which a director is fired is that Donner had been making Superman and Superman II simultaneously, so much of the footage he intended to use for his film already existed. Lester rewrote and reshot much of the film during his time at the helm, which is what audiences saw when Superman II was finally released.

As years went by, the legend of Donner's unreleased version of Superman II grew, and in 2001 editor Michael Thau, who was working on a restoration of Superman, came across the original reels containing Donner's unused footage. Thau approached Donner and asked if he'd be interested in supervising a new cut of the movie, which featured significant departures from Lester's film and became something more like what Donner had intended. Donner and screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz supervised and consulted on Thau's editing, and Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut was finally released on DVD in 2006.

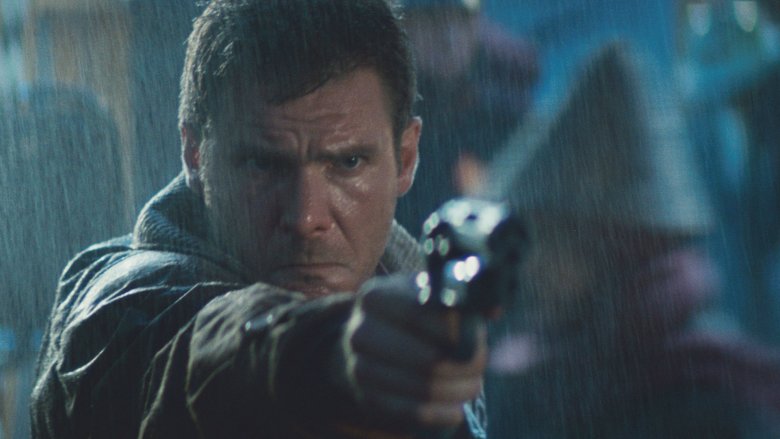

Blade Runner

Few films have ever received quite as much re-editing attention — or fan interpretation of the various re-edits — as Blade Runner, the 1982 sci-fi classic about future cop Deckard (Harrison Ford) hunting rogue synthetic humans known as replicants. The original theatrical version of the film was not the version director Ridley Scott wanted you to see, as it contained various voiceovers by Ford in an attempt to help explain the backstory, as well as a studio-mandated happier ending.

In 1992, a new version of Blade Runner was released that dropped both the voiceover and the happy ending. Dubbed the "Director's Cut," this version of the film popularized the fan theory that Deckard is actually a replicant himself, as the new cut helped emphasize the thematic ambiguity Scott had always intended.

Sadly, despite its improvements, Scott himself did not fully supervise the "Director's Cut" of the film, and in 2007 he opted to remedy that with what's become known as the "Final Cut" of Blade Runner. With Scott's direct supervision, this cut of the film further plays up the Deckard-as-replicant interpretation, adds in some scenes previously only seen in international releases, and features a full restoration done under Scott's watchful eye.

The Godfather and The Godfather Part II

Any list of the greatest films ever made almost has to include both The Godfather and its sequel, The Godfather Part II. Both films are masterclasses in acting, writing, direction, cinematography, and just about everything else, and both earned Academy Awards for Best Picture in their respective years. There's absolutely no reason for editors to mess with either film... unless you're planning a lucrative recut for television, that is.

This was the case in 1977, when Godfather trilogy director Francis Ford Coppola signed off (in part to earn money to finance Apocalypse Now) on a massive, seven-hour recut of the first two films titled The Godfather Saga. The intention was to repackage the films as a TV miniseries, and as a result, NBC cut the films together in chronological order, beginning with young Vito Corleone's (Robert DeNiro) arrival in America as a boy at the dawn of the 20th century and ending with Michael Corleone's (Al Pacino) final descent into darkness in the late 1950s. This new cut, which has since been slightly lengthened and retitled The Godfather Epic for an HBO presentation in the 2010s, also includes various previously deleted material from both films. Ambitious and vast, The Godfather Epic lives up to its name, but it loses something in the translation, particularly the contrast between Vito and Michael that's created by the flashbacks in Part II.

Exorcist: The Beginning/Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist

The story of the prequel to The Exorcist is not so much the tale of a film being re-edited after its release as it is the tale of an entirely new movie emerging after the first film's release, which is made even more complicated by the fact that the second film to be released was actually the first film.

It breaks down like this: screenwriter William Wisher and director Paul Schrader teamed up to make a prequel to The Exorcist centered on an exorcism that Father Merrin (played by Stellan Skarsgård in the prequel) performed in Africa right after World War II. The film was meant to be a cerebral drama with supernatural elements, but when James Robinson, owner of Morgan Creek Entertainment, began seeing footage from Schrader's film, he grew worried that the project wouldn't be a success. Schrader was ultimately fired, and director Renny Harlin was brought in for what started as reshoots, but soon became an almost entirely new production with many of the same story beats, cast members, and sets.

Harlin's film was released theatrically as Exorcist: The Beginning, but Morgan Creek was not yet done with the property. Perhaps hoping to recoup their full investments, which now included two productions, the studio called Schrader back in to recut his own footage (with a bit of Harlin's thrown in) to finish his original film. Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist was later released on DVD. Neither film was particularly well-received, but the making of them both is quite a story.