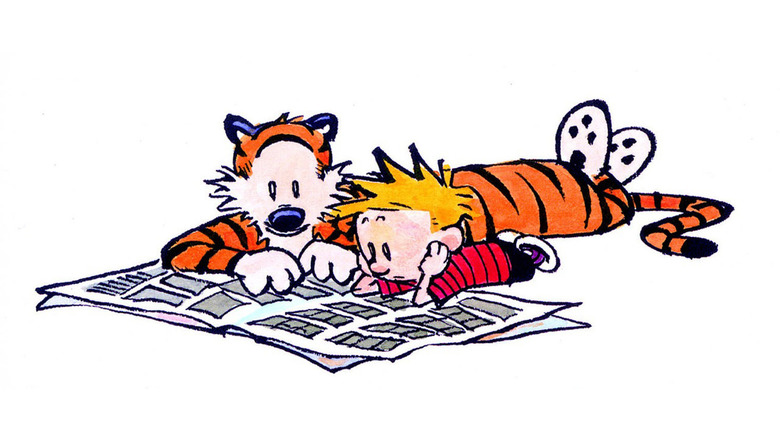

Fight Club Is A Calvin & Hobbes Sequel Says One Fan Theory

There are a lot of wild fan theories floating around on the Internet, to put it ever so lightly. One of the most lurid ones you'll find, though, draws an unexpected connection between a David Fincher film and a heartwarming comic strip.

Specifically, one blogger, Keith Buster, proposed a theory back in 2008 regarding the 1999 Fincher classic "Fight Club" (based on Chuck Palahniuk's novel) and Bill Watterson's beloved comic series "Calvin & Hobbes." It's easy enough to see some basic parallels between the two at face value. In "Fight Club," Ed Norton's unnamed main character befriends a mysterious, dangerous man named Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) and ends up living on the edge with him, but it turns out — spoiler alert for a really old movie — that Tyler and the narrator are actually the same person. Somewhat similarly, in "Calvin & Hobbes," six-year-old Calvin's best friend is his stuffed tiger Hobbes, who's only ever seen as alive through the young boy's eyes.

This theory takes things a step further, though, and argues that Norton's protagonist is Calvin, but an adult version of the imaginative child. To take it further, Hobbes reappears to this character as Tyler later in life to save him from the mundanity of his everyday existence. Buster lays out plenty of evidence, and concludes thusly: "Calvin is perpetually six years old [...] Because of this, our hero is free to do as he wishes, free to chase his dreams as wildly as he desires, never having to worry about tomorrow because there essentially will never be one [...] This makes the reality of Fight Club all the bleaker, because it depicts what happens when you take someone weaned on dreams and limitless possibilities and jam him into a cramped cage confined by rules and regulations."

Could Fight Club be a continuation of Calvin & Hobbes?

Okay — let's break this down. The fan theory imagines that, years after the events of "Calvin & Hobbes" — namely, Calvin's unfulfilling, bleak adulthood where he's so desperate for companionship that he hallucinates a whole guy and starts a fight club under said guy's identity. Again, it's important to note that Calvin does have a vivid imagination, though it's probably not totally out of the ordinary for a six-year-old to truly believe that his beloved stuffed tiger is not only really alive but also his thoughtful, loyal best friend. All of this makes both projects much, much sadder, though.

Keith Buster takes this thought to the extreme in his blog post. "This makes the reality of 'Fight Club' all the bleaker, because it depicts what happens when you take someone weaned on dreams and limitless possibilities and jam him into a cramped cage confined by rules and regulations," he wrote. "It probably only took poor Calvin a few years in the adult world (or growing-up world) to fully make the sad change."

Considering how popular both of these properties are, it stands to reason that there are people out there who are fans of both "Calvin & Hobbes" and "Fight Club." Clearly, Buster is one of them. It feels somehow wrong, though, to look at a sweet series like "Calvin & Hobbes" and surmise that it could turn into something as depressing as "Fight Club."

Imagining Fight Club as a sort of sequel to Calvin & Hobbes is unrelentingly dark

"Fight Club," in case anyone forgot, is one of the darkest movies around. Even before Edward Norton's unnamed narrator starts "hanging out" with Brad Pitt's Tyler Durden, his life is unspeakably bleak; he hates his job and goes to support groups for addiction and illness just to feel ever-so-slightly less alone. The only reason that Norton's character and Tyler start living together in the latter's run-down house is because the narrator's apartment is ruined in an explosion. Even the narrator's relationship with the difficult Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) is fraught because, before the audience learns about the narrator's split personality, it seems as if Tyler is the one involved with her; the narrator simply dislikes her.

"Calvin & Hobbes," on the other hand? It's an acerbic but fundamentally sweet story of what it's like to grow up with a big imagination, and it's gutting to imagine that Calvin's fate would be to become Norton's narrator. Keith Buster's fan theory certainly is fascinating, but if you'd like to still enjoy "Calvin & Hobbes" without going down any mental rabbit holes, it might be best to discard this particular thesis.