The Dune Movies But Without Special Effects

The spice must flow — and so must the special effects in the new "Dune" movies. Director Denis Villeneuve's take on Frank Herbert's iconic but supposedly "unfilmable" sci-fi epic book series is a smash hit, and loved as much for its striking visuals as it is for its oddly-shaped popcorn bucket. "Dune" is about heroism, fanaticism, and the price of power — especially on the harsh desert planet, Arrakis. This planet is, spoiler: full of dunes. It's also full of spice, a powerful substance that in small doses provides mind-opening visions, and makes space travel a quick trip — literally.

Arrakis is the only planet in the galaxy that contains spice, and its Fremen people have long been oppressed by violent colonizers mining the stuff. But when noble youth Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) shows up in Arrakis, everything changes ... or does it? Time — and trippy scenes of sweeping sandscape space visions — will tell.

"Dune: Part One" took home Oscar gold for its stunning, photorealistic depictions of the Known Universe. The visuals only get bigger and better in "Dune: Part Two" — but they stay grounded. Even powerhouse director Christopher Nolan thinks so. "It's one of the most seamless marriages of live-action photography and computer-generated visual effects that I've seen," Nolan told The Hollywood Reporter, in praise of Villeneuve and his team. Making "Dune" so visually futuristic and believable took more creativity and teamwork than learning to ride a sandworm. Sniff a bit of spice and read on to get a glimpse of the "Dune" movies without special effects.

Sandscreens, not bluescreens

Believability is the watchword for the Denis Villeneuve "Dune" movies, and yet, they're science-fiction movies set millennia from now. The production didn't escape the use of computer-generated (CG) visual effects (VFX), but it did escape making its actors and environments look like cut-outs against a clearly-keyed-in bluescreen. So how did the production avoid the typical superhero movie trap, and instead make the "Dune" movies look like National Geographic went to space in the year 10,000?

The answer is sand. Or, more accurately, sand-colored screens that stretch as wide as football fields. These sandscreens worked as a bluescreen that matched the color of the desert daylight filmmakers were after, and also helped them extend and manipulate practical sets, environments, characters, and the like digitally. "We found that when you put the sandscreen in the negative, it becomes blue. So it's an inverted blue screen," Villeneuve explained in a making-of interview.

Watch for the sandscreens you can't see in the finished film of "Dune: Part One" — especially the scene when the Atreides family first lands on Arrakis, and when Paul walks the Palace at Arrakeen grounds to observe the sacred palm trees. In the landing scene, sandscreens are used to extend the environment beyond the landed ship. In the palm tree scene, sandscreens stand in for the palace in the background.

Muad'Dib

While the "Dune" movies explore the great and terrible power that being a charismatic leader can come with, they also star an adorable little mouse. And no, we're not talking about Mr. Chalamet. The desert mouse that audiences first meet after Paul and Lady Jessica's (Rebecca Ferguson) sandy escape in "Dune: Part One" is called the Muad'Dib.

This little kangaroo mouse may be small, but it is mighty; it creates its own moisture in the arid land of Arrakis, and when it comes to Paul in "Dune: Part Two," it points the way. In the movie, the creature is not just cute — it looks like a living, breathing thing. This is the work of intensive CG animation, aided by an adorable stuffie stand-in.

"We had designs from Weta Workshop, which we tweaked and tinkered with. And once Denis was happy, we went to props and had that built," visual effects supervisor Paul Lambert told Befores and Afters, adding: "It was actually quite expensive ... and that was going to be our reference for when we shot in the desert." The photorealistic reference stuffie combined with CG modeling and animation created, in the end, a believable little desert creature you just might pledge your life to. As Lambert said: "Everybody loved that little mouse."

Transformer sets

Patrice Vermette served as the production designer for "Dune: Part One" and "Dune: Part Two." He worked in partnership with multiple departments, practically and digitally, to pull off an entire galaxy with a big — but tight — budget. The name of the game was immersion, and Vermette helped create as much practical magic as possible via collaboration, creativity, and materials you might not expect.

"Patrice Vermette had to be very, very creative with space. The sets were like Transformers," Denis Villeneuve explained in making-of footage. For example, in "Dune: Part One," Duke Leto's (Oscar Isaac) room doubles as Duncan Idaho's (Jason Momoa) room. After the space was dressed for each character's parts, lights and VFX were added to bring the scenes to life — and block out the wood scaffolding behind the sets. "We went old-school Hollywood," Vermette told Elle Decor. And of Villeneuve's immersive approach, he added, "I think it helps everyone on the team get into the mood of what we're doing."

Vermette and his team also used interesting materials to create ceilings for CG artists to better manipulate in post. During the lab scene, the spoked ceiling is made of fabric, which allows teams to better manipulate texture effects and actors to be lit naturally from sunlight above. Vermette also explained to Elle Decor that filming on the soundstages in Budapest had its difficulties. "The challenge was it was the rainy season," he revealed. In addition to rain wetting the shoot's considerable sand, he added, "There was the wind factor ... our fabric ceiling had to be super tight."

Ornithopter ships

Ornithopters are the vehicles "Dune" characters fly around their new home planets in style — or, you know, while under attack from House Harkonnen and the Sardaukar. They look as if a helicopter and a dragonfly had a baby, and that baby grew up and hit the gym. Even more than their militaristic, insect-like muscularity, the ornithopters look real. And what's more — they kind of are.

"I want my mother to believe that this thing can fly for real," Denis Villeneuve said in behind-the-scenes footage. In order to achieve that reality, teams practically built the body of the airships to scale, then placed them on gimbals (mechanisms that can pivot) to create ship movement for actors and stunt performers in real-time.

In an Ornithopter featurette, Patrice Vermette described the scale of the 11-ton ships: "Wingspans are 129 feet." While the ships couldn't actually fly, they sure looked like they could; cranes lifted them for take-off and landing, which were composited with footage of helicopters actually taking off and landing. The final product looks flight-ready to the naked eye — and feels like it, too. In making-of footage, Timothée Chalamet said: "It felt like a real thing. It felt like it was something you wanted to strap into. You wanted to put your seatbelt on."

Ornithopter light

The ornithopters of the "Dune" movies are a far cry from rear-projected car scenes of yore — but much like driving scenes in sitcoms or any movie, ornithopter flights had to contend with the ships covering a lot of ground and moving through naturally shifting desert light. Whether they were used to survey the spice mines of Arrakis or being flown in a fight for their pilot's lives, designers and animators worked creatively to make ornithopters look as fully functioning as they felt for the actors.

This was achieved by really filming interior ornithopter scenes outside. Paul Lambert told Befores and Afters: "We went out and scouted and found the highest hill in Budapest, and we built our gimbal on top of this hill so we could get a nice flat horizon, and then around the gimbal we constructed a 25 foot high, sand-colored, 360-degree ramp. What we called it was the 'dog collar,' which circled the entire gimbal."

Sun would reflect off the "dog collar" and fill the ornithopter interior with perfect, natural desert light. Director of photography Greig Fraser could capture his scenes lit this way, and his shots would later be composited with separately filmed plates (think: long clips) of real-life flight footage. When Fraser focused on actors in the ship and left the background just out-of-focus, Lambert said, "It almost looked as if you were over the desert."

Ornithopter flight

In addition to handling the light of ornithopter travel through Arrakis, "Dune" filmmakers also had to create the actual look and feel of flight. They did most of this digitally through the addition of wings to each ship, duplicating ships digitally, and compositing animated additions with helicopter reference flights, sand swirls, flight plates, and footage of the actors in the life-size ornithopter bodies.

"There was a lot of work done to get a range of motion as to how this ornithopter flies," Paul Lambert explained. "Also, you have people like Duncan Idaho, and you wanted to give it a certain swagger, as well, as he flew." Determining how an ornithopter worked, what its flight capabilities really were, and what swagger could even be possible while flying it started at the animated roots.

Many different animation vendors worked on the "Dune" movies, with a major player being DNEG. "We tried different wing movements and different landing styles. Each wing actually moves in a figure eight like a bird ... The rendering on it was off the charts just to get them to work," DNEG animation director Robyn Luckham explained to Animation World Network. "We created a bible for Denis of how the ornithopters would move around space," he added. "When Denis uses the phrase 'I deeply love it,' you know you've hit a home run. We hit it with the ornithopters."

We agree — the animation here is top-flight.

The Baron

Stellan Skarsgård plays baddie Baron Vladimir Harkonnen in the "Dune" films. The Baron's size is often described in Frank Herbert's books, and Skarsgård fittingly plays his part in a prosthetic suit that's larger than life. It makes him look part sandworm and is augmented with enough hardware to drive Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne) from "Mad Max: Fury Road" more mad with envy.

Skarsgård sat in the makeup chair for hours getting prosthetics and makeup applied — but he didn't have too many complaints. "I mean, you go into a sort of fatalistic Zen. But ... I also enjoyed the people working on me," he explained to GQ. "They were a crew of five, and they were very funny, and lovely ... The painting work they did — it was like watching Michelangelo work."

Head makeup designer (and long-time Denis Villeneuve collaborator) Donald Mowat cautioned Villeneuve against wading into bad comedy territory with the suit. "You also need to be respectful, you're not fat-shaming other people," Mowat explained to The Italian Rêve, adding, "It's okay to be fat and we were very careful about that, so I said to [Villeneuve], "Let's try." Eventually, Mowat, Villeneuve, and the combined efforts of their teams led to a design that made it into the movies — and, in the case of "Dune: Part Two" — into a disgusting black oil bath. Skarsgård insisted to GQ: "It was perfectly temperate. It was warm. It was nice." We'll just have to take the Baron's word for it.

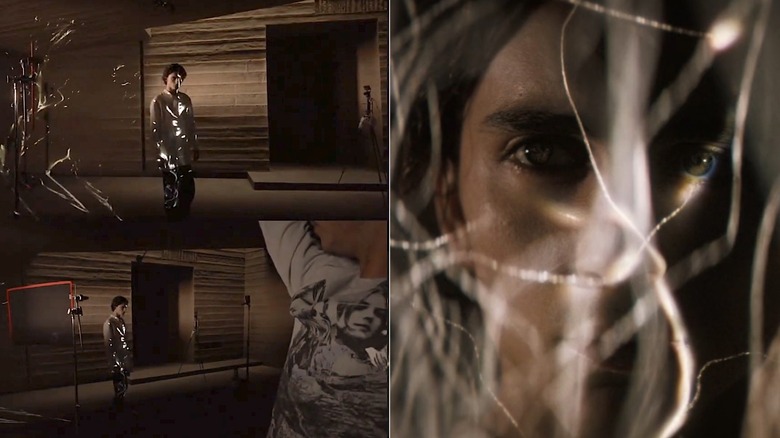

Blue eyes

Spice-spiked blue eyes are an iconic hallmark of the "Dune" movies. Whether someone is a maybe-magic-messiah figure hitting The Water of Life pretty hard, or a Fremen rebel like Chani (Zendaya) exposed to spice daily, being around the stuff all the time causes eyes to turn blue. While the blue eyes literally seemed to glow in the 1984 "Dune" movie by David Lynch, Denis Villeneuve and his team aimed more for realistically spicy eyes.

Paul Lambert told Befores & Afters that over 1,000 shots of blue eyes were needed for the second film. "We came up with a different technique, using what we'd learned before from the hundreds of blue eye shots in the first movie and creating a machine learning model, an algorithm trained from those 'Dune' shots to find human eyes in an image, which would then give us a matte for the different parts of the eye," he explained. "We then used this multi-part matte to tint the eyes blue." Lambert's team would sometimes hand-adjust blue eyes to make sure the right characters and extras were shining like Sinatra — and that no random Harkonnen or Sardaukar got the wrong blue steel.

While this process seems arduous in itself, it could have been worse. "We did a test where we cut up some onions and we rubbed them under our eyes to try and get some red going on from the onion which we then tinted blue," Lambert told Befores & Afters, adding: "Denis wasn't interested in that."

The hologram tree

Paul Atreides has to hide out to evade attack during "Dune: Part One," and the best place for him to momentarily escape is a holographic creosote tree projected by his filmbook. It's a gorgeous and scary scene that looks too real to be CGI and too mystical to be fully real — because the effect is really achieved with a wide variety of practical, digital, and in-camera magic.

Paul Lambert and his team knew they couldn't create a full-out hologram for their shoot, but needed to find a way to get some of the hologram's light onto Timothée Chalamet. The team experimented, then ended up getting Denis Villeneuve to approve a design for the tree very early in pre-production. Then they fragmented that image into hundreds of slides.

Lambert told Digital Trends: "We then got an old-fashioned projector and projected each slice on him, based on where he was on the set. So as Paul moved, you would get a different slice being projected on him and around him. And as he moved forward, you would get one slice after another, as if he was moving through the branches." Post-production teams were able to add in and animate the rest of the tree after the fact, using the light Chalamet really did physically interact with as the base of this hauntingly beautiful scene.

Sandworm movement

Animators, sound designers, and other "Dune" filmmakers took inspiration from the sea to create the massive, slithering Shai-Hulud — aka, big ol' hungry sandworms. While Paul Lambert and his team initially looked to earthworms for design inspiration, the biologically accurate worms they came up with lacked interesting movement.

But when Lambert and his team likened the worms to whales, they got somewhere. Of course, since the worms are seen sparingly in "Dune: Part One," they also call to mind other sea-spiration. "It's technically 'Jaws,' when you don't see the worm but you know it's there," Lambert told Vanity Fair.

When worm riding became a major aspect of "Dune: Part Two," Denis Villeneuve's producing partner (and wife) Tanya Lapointe took charge of the "Worm Unit" to handle riding scenes, as they were that massive an undertaking. And still, mind you, shot outside. "Just because there are no real sandworms, doesn't mean we're going to go on to a soundstage," Fraser told Empire, adding, "We were outside shooting sandworms in the real sun with real wind and real dust. Just because you don't have one small element, doesn't mean you throw away the entire concept of being honest and real."

Sandworm snacktime

Maybe even more frightening than sandworms slithering through the dunes is the moment one opens its mouth and sucks in anyone or anything unlucky (and loud) enough to have summoned it. Animators and filmmakers looked to the mouths of whales to create their CGI models — and took cues from how baleen traps its tasty little morsels.

Robyn Luckham and his animators worked with a variety of teams to create hundreds of muscle animations for each circular baleen tooth the sandworm has and worked on appropriately animating the beast's throat. "We studied footage of the inside of a 'beat-boxers' larynx on how the throat would be affected by sound," Luckham told Art of VFX. This allowed for creative sound design, especially for the "Dune: Part One" scene where a sandworm sucks down a spice crawler.

Sound department genius Mark Mangini stuck a microphone down his own throat and "sucked for as long as I had lung power for," he told Vanity Fair. "Sometimes, there are simple solutions to complex problems." Paul Lambert's team also figured out how to make it look like actors were sinking into the sand when a sandworm got close. As he explained to Befores & Afters, they actually sank them, using a large remote-controlled plate buried in the sand that would shake actors and lower them as needed.

Harkonnen home world

Giedi Prime is the grisly, plastic, black and white Harkonnen homeworld first glimpsed in "Dune: Part Two." The scenes and sets there harken back to gladiator films and Hitler orations — and they're supposed to.

"I came up with this idea as I was writing the screenplay," Denis Villeneuve told Polygon, adding: "Of course, Greig Fraser went on board big time with it." Fraser has used infrared before, and told Variety, "It's the same light the security camera uses, and you don't see it. So, my fascination with infrared started because our eyes can't see it, but the camera can." Fraser modified an Alexa LF into an infrared camera, and it was off to the races — er, rigged battle to the death.

Austin Butler is nearly unrecognizable in his Feyd-Rautha makeup, along with his voice — modeled after his character's uncle, The Baron. "The first time I met him, he showed me his — my voice. He studied it in many films," Stellan Skarsgård told GQ approvingly, adding: "Ah, it was like seeing myself." Sounds like Butler's skill with real-world voice work is a powerful special effect unto itself.

Shields

How slow is your blade? The shimmering body shields worn by the characters of the "Dune" movies look just as photorealistic as the interactive light blended with animated light in the holograph tree scene, but they are actually animated entirely in post — with a lot of playing around in pre-production to find the right technique.

Animators played with effects using a clip from "Seven Samurai" before shooting began. "One of my artists processed an image from the film to blend past and future frames together," Paul Lambert told Digital Trends. "I then had the artist go in and paint back the original frames a bit or paint in some of the effect, because I wanted it to feel more analog."

Using the color blue to show the shield had provided protection (because a move was too fast) and red for damage (from a slow enough blade, as it were) was an innovation made for the films, deep into the post process. "You couldn't really work out what was going on because of the intensity of the fighting, and that's where the idea of the color came in," Lambert said in a DNEG featurette. This effect is best on display in the training scene between Gurney (Josh Brolin) and Paul in the first film.

Use the voice

One of the biggest memes from "Dune: Part One" is when Lady Jessica commands Paul to "use the Voice" to make him give her a glass of water. The Voice is the name of a Bene Gesserit manipulation tactic and the perfect embodiment of one of the movie's major questions of power: Is it taken? Is it earned? Is it forced? Does it matter? The Voice is manifested in the movies as a blend of multiple voices, which creates a spooky, slightly disjointed choir of ancestral chatter telling people what to do. This is by design.

As Denis Villeneuve described while breaking down the Voice-heavy Gom Jabbar scene, a pivotal test of will that ends in a poison needle to the neck of what counts for triumph to a Bene Gesserit. "I was obsessed by the idea that when you use the voice, you should be channeling an ancient voice inside yourself," Villeneuve explained to Vanity Fair. "I love the idea that you will channel the voice of very ancient powerful grandmothers." He later added that with the help of the costume design and her impeccable acting, "Timothée was afraid of [Gaius Helen Mohiam actress] Charlotte Rampling for real."

The voices of three elder actresses played over whoever used The Voice in "Dune: Part One." One voice belongs to rock & roll legend Marianne Faithfull — who, surprise: is friends with Rampling from their younger days.

The kiss

While the "Dune" films are wonders of VFX and special effects, perhaps why they are so visually stunning is they incorporate as much of the real world and practical effects as they possibly can.

Even the long-awaited kiss between Paul and Chani in "Dune: Part Two" depended less on CG than a real-life Unesco World Heritage site. Zendaya was amazed at the locations the productions got to shoot in, including the Wadi Rum desert of Jordan. She was overcome with emotion describing the scene to Florence Pugh at IGN FanFest, saying: "It's the big Paul and Chani kiss, and it's like, sweeping, and that is just practical ... I remember being on the day, like, whoa – this is real."

Other shooting locations for the "Dune" films include Norway, Italy, and Budapest. In addition to shooting in real locations and showcasing natural landscapes, the "Dune" films also used a lot — and we mean a lot — of sand. "We were forever blowing sand around," Paul Lambert told Befores & Afters. "The SFX team actually used 18 tons of dust/sand during the production." Fear might be the mind-killer, but sand is a close second.