Characters Who Were Much Better In The Sequel

In the thrill-a-minute world of filmmaking, it can be difficult to find just the right way to portray a character. It takes the combined efforts of the actor, the writer, and the director, all meshing as a single cohesive unit. Often times, just one movie isn't enough to get the proper end result. Occasionally, as with Rob Base/DJ EZ Rock collaborations, it takes two to make a thing go right. Or, you know, three, or four, or a prequel series.

It's by no means a rule (we're looking at you, Ellen Ripley), but sometimes the progression of a franchise can flesh out its characters in unexpected and wonderful ways. Goofballs get serious, serious folks goof off. Occasionally, someone will learn to use the Force out of nowhere. Here are a few of the times when sequels made us love our imaginary movie besties even more than we already did.

James Norrington, Pirates of the Caribbean 2

2006 was a simpler time. Millennials were young and doe-eyed. We still trusted the Hollywood system to care for the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise like the beautiful creature it was and not milk it until its udders got chapped and scabby. The first of the Pirates sequels makes a lot of bold changes to the mythology. It introduces new characters like Davy Jones, the first tentacle-faced Scottsman to appear in a major motion picture since Sean Connery. It also reintroduces us to old favorites with new twists: Pintel and Ragetti are back and religiously motivated. Elizabeth is here and doing sword things now. Jack Sparrow isn't all that annoying yet.

But the real star was James Norrington. A secondary antagonist from the first movie, he'd been less "straight up villain" and more "guy your girlfriend's dad wishes she was dating instead of you." He had a great job and knew how to dress up pretty. His only character flaw was the stick up his keister, which Dead Man's Chest unceremoniously removes without so much as a "close your eyes and think of England." In the sequel, Norrington has been stripped of rank and dropped in a bottle, sent to Tortuga to slowly succumb to liver failure. He's more watchable and likeable for it, and he becomes the mascot for a phenomenon we'll see a lot here: the grimier the character gets, the more they improve.

Pippin, Lord of the Rings: Return of the King

Let's talk about Peregrin Took. At the start of the Lord of the Rings movies, he's one half of a renaissance fair stoner comedy duo with his best friend and cousin, Merry. They like smoking pipes, they like eating food. They're just about all the levity that the audience gets in an otherwise dour series of van art paintings come to life.

Skip ahead to the third movie, and Pippin is separated from his BFF. He's out of pipe weed. He's in the employ of a greasy lunatic. He also gets real murdery out on the battlefield, stabbing a troll to death while the most powerful wizard on Team Good Guys wields a very cinematic horse-mounted flashlight.

And if you really want to go down the "actually, in the books" rabbit hole, he also sort of went all William Wallace on a bunch of orcs that tried to rally up a revenge ride on the Shire. The point is, Pippin goes from dry-eyed scamp to slaughter munchkin in less than one trilogy, putting him in the top two most lovable three foot tall murder monsters Billy Boyd has ever played, second only to Glen in Seed of Chucky.

Wolverine, about half of the X-Men movies

There was a good long while there where comic book movies were considered kid-centric, hokey, expensive, and dumb. It took a while, but eventually studios started to figure out that colorful characters with decades of backstory to borrow from had, you know, potential. They could be exactly as complex and layered as you wanted them to be.

Case in point: Wolverine. On the surface, he's a cranky man with hands that cut things, making him the original Slap Chop. But delve into the source material, and you've got nigh on fifty years of stories about his origins, his life, and the ways that over a century of physical trauma and water bed accidents can wear on a guy.

And the movies got it right, like, half of the time. Roughly the first 20 minutes of The Wolverine, for example, are less an action figure commercial and more a heartbreaking independent film about psychological damage, loneliness, and regret. Do ninjas show up a few minutes later and break the dramatic tension? Yeah, but what are you going to do? The picture also ends with Wolverine fighting Super Shredder. Making movies is hard.

Thor, Thor Ragnarok

It's been a while since anyone has had to admit this, but Thor was a notoriously difficult character to put on screen. By the numbers, he's a Viking god with vague lightning powers and a hammer that he spins really, really fast until it makes him kind of fly a little bit. So when 2011's Thor rolled around and gave us a take on the character that was something you could sit through without your eyeballs burning, audiences responded with a mighty "good enough." Then Thor: The Dark World got everyone saying pretty much the same thing, and the world resigned itself to just not particularly looking forward to Thor movies moving forward.

And then, seemingly out of nowhere, someone at Marvel must've said something like "remember that one time Thor made a joke? What if we did that but like, as a whole movie?" Thor: Ragnarok was born, and all of the God of Thunder's over-the-top character traits became self aware caricatures of themselves. Somehow, the comedic tone didn't detract from the more dramatic moments, and the dramatic moments didn't feel like a "very special episode" of a sitcom. Overall, it set a unique and exciting tone for a character who could've been unremarkable, beginning a legacy of comedically balanced Thor storytelling that would last until the Russos went "what if we gave him a Santa tummy?" two years later.

Tony Stark, Iron Man 3

In the neverending panoply of superhero movies, 2008's Iron Man is rooted firmly in "great for its time" territory. Consider that up to that point, the most successful big screen superhero franchise had ended with Tobey Maguire slow dancing with Kirsten Dunst to apologize for punching her, and that for every X2 there were three or four Nic Cage Ghost Riders, Ben Affleck Daredevils, and Halle Berry Catwomans waiting to break your heart.

The problem with Tony was that he was too awesome to be interesting, with "awesome" being used here the way it generally is when a guy who still uses hair gel slams a Vodka Red Bull at a Buffalo Wild Wings. He was cocky, overconfident, and egotistical. His whole mission statement came down to "Darn it, I was too good at making stuff explode, so now I've got to explode the exploding stuff I made with even better stuff that explodes stuff."

So it was pretty refreshing when Iron Man 3 came out. Even with its divisive narrative and perceived lack of robot suit screen time, it really manages to shine when it comes to painting Tony as a human being. Here, he's a vulnerable person, terrified of what the events of The Avengers have done to change his worldview. It's a shockingly humanizing turn, even if you are still bitter about the Mandarin.

Sarah Connor, T2: Judgement Day

In The Terminator, Sarah Connor is a half-waitress, half-MacGuffin chimera who asks a lot of questions and eventually accepts her destiny as human incubator for the savior of the world. It was 1984, and the Bechdel Test wouldn't start gestating in the public consciousness for another year or so.

In Terminator 2: Judgement Day, Sarah Connor is what you imagine when you close your eyes and think of who you wouldn't want to meet in a dark alley. She is a lean, fury-eyed human leopard with apparent proficiency in every form of deadly weapon. She's been institutionalized for being too categorically badass.

Then came the dark years. Terminator 3, Terminator Salvation, and Terminator Genisys didn't really do any of the series' characters any favors. With any luck, 2019's Terminator Dark Fate and the return of Linda Hamilton will usher in a new era of Amazon Alexas experiencing Sarah Connor panic nightmares.

Batman, The Dark Knight Rises

It's been nearly 15 years since Christopher Nolan inadvertently birthed the rise of the dark and gritty superhero movie with Batman Begins. Up to that point, Tim Burton's Batman Returns was the darkest on screen iteration of the character audiences had seen, and it played less like a true crime biopic and more like an ambitious Cirque du Soleil/Hot Topic cross promotion.

Begins was followed by The Dark Knight. Opening like gangbusters both critically and financially, the sequel has a lot of moments that've probably burned themselves into your memory. As you look back, though, practically none of them probably have much to do with Batman. It was weird that it happened and even weirder that it worked, but Batman was almost a background character in his own movie; more a part of the landscape and a vessel for theme than a human being affected by the story.

So it was a punch in the gut when The Dark Knight Rises rolled out that scene where Alfred admits that he burned the letter from Rachel. It's quiet and it's subtle, but that's the first time in seven years of movies that we see Bruce Wayne exhibit more than a half-hearted sociopathic glance at feeling emotions. Seeing a guy who's been wingsuiting into skyscrapers and Monster Jamming traffic jams for two movies staggered by something as personal as a lie his friend told him is still the closest we've gotten to a human Batman.

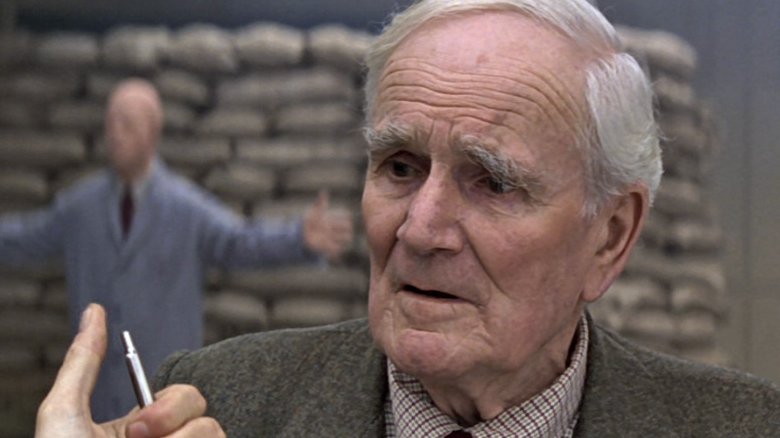

Q, 007

Imagine that your job, as assigned to you by those charged with protecting the country you love, is to come up with outlandish new inventions. Remarkable inventions. Devices so far ahead of their time as to border on supernatural to the casual viewer: helicopters that can be packed in a suitcase and compressed air cannons and lint brush cell phones. Now imagine that a sex-crazed psychopath showed up to your office once a week, threw your work in the trunk of his car, and promptly blew it up. You would, very rightfully, blow a blood vessel in your right eye and start drinking too much. This, in a nutshell, is the life of Q from the James Bond movies.

Q starts out inauspiciously enough, first introduced in From Russia With Love. His part is brief and to the point: he's put together a suitcase full of murder for 007, and the look of optimistic excitement in his eyes is almost heartbreaking when you realize that, from this point forward, every project that he pours his heart into will be systematically burned, blown up, or shot into space by Bond. Maybe that's why it's so beautiful that Q's hatred for Bond is seemingly the only continued plot thread through all of the pre-Daniel Craig movies. Every time that Q returns, it's with even more scalding vitriol in his heart. Blofeld, Goldfinger, and Kananga combined will never hate Bond the way Q does by Tomorrow Never Dies.

Max, Mad Max: Fury Road

At a certain point, the particulars of a character aren't as important as their place in the world they inhabit. Disney put that together when they realized we didn't need a ninth reimagining of the Spider-Man origin story in order to make the audience understand Spider-Man. The killer from Se7en is defined by the way he changes the story, not background information about what drives him.

The same goes for Max in Mad Max: Fury Road. From the opening narration forward, we're not given a ton of material to draw from if we want to define his character. We know he's a survivor, and that he's less of a jerk than the bad guys. In point of fact, we're told so little about him that there are popular fan theories that he's not the Max Rockatansky from the first three movies at all, and while you can't prove that they're right, you sure can't prove that they're wrong.

And you know what? That's alright. A character who's, in practice, divorced of any connection to previous events wound up being a lot more compelling. From the lack of flashbacks or explanation to his general lack of dialogue, less really was more.

Kirk, Wrath of Kahn

For three years of Star Trek (two more if you count the animated series), TV audiences got to know James Kirk, captain of the USS Enterprise. He was a swashbuckling, confidence-exuding, personification of masculine heroism. He was what would happen if the word "swagger" came to life and put on polyester pants. There wasn't a problem in the galaxy that he couldn't argue, torpedo, or awkward-'60s-closed-mouth-kiss his way out of.

15 years, two cancellations and a weaponizably boring first movie later, there was Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn. The sequel got a lot right, and one of its best features was the way it asked "Can you imagine how damaging an episodic adventure lifestyle would be?" It showed Kirk as a man who was aging hard, and whose wild days were finally catching up with him. All of the problems he had grinningly warped away from still existed, and they hadn't moved on. The women he'd womanized? At least one of them had ushered a little Kirk into existence. It was jarring to see a character originally conceived as a means by which to tell short stories faced with the fact that those stories don't go away when you stop paying attention to them.

Gabriel, The Prophecy 3

The Prophecy is a 1995 horror thriller that has, in large part, been forgotten, as evidenced by the fact that it's one of maybe 12 '90s genre movies that nobody's trying to reboot. It's a not so great film with a few bright spots: Viggo Mortinson shows up as the Devil, Amanda Plummer is her usual level of inhumanly charming, and most importantly, Christopher Walken plays an evil take on the angel Gabriel. It never really gels, and it made next to no money, but damned if it didn't go on to spawn four sequels, which were... worse.

Really, there's next to nothing to love about the rest of the films in the series, with one exception: during production on 2000's The Prophecy 3: The Ascent, some sort of miracle must have happened. Maybe the director got bored or the writers got tired, but by all appearances, somebody made the decision to stop writing dialogue for Christopher Walken and just kind of let him talk. And talk he does. At one point, he sits at a diner from the first movie and orders breakfast for something like a full minute. Imagine a mid-level improv comic going to Denny's and ordering everything on the menu in a Christopher Walken voice, because that's exactly the energy that's brought to the scene.

The lesson here is, if you can't make something good, you can at least make it so weird that it's impossible to look away.

Jar Jar, Star Wars: Episode I

20 years and several Star Wars movies later, it would be almost impossible to say anything about Jar Jar Binks that hasn't already been said. Still, for the sake of the folks in the balcony and anyone just coming out of a coma, here's a refresher.

1999 saw the release of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, a picture 22 years in the making which featured Darth Vader as a pinchably-cheeked young sweetheart and a total of zero phantoms. Fans were disappointed by the movie's light, childish tone, and pointed to Jar Jar as the poster boy for everything wrong with the "new" Star Wars. He was a troublingly computer generated Goofy/salamander hybrid with a pattern of speech that was at best annoying and at worst super duper problematic.

But if you stuck with the series, your patience was rewarded. In Attack of the Clones and even more so Revenge of the Sith, the character is vastly, dramatically improved upon in the best way possible: there's way less of him.