We Finally Understand The Ending Of Breaking Bad

In the annals of TV history, Breaking Bad will undoubtedly go down as one of the best television shows of all time, right there along with The Wire and The Sopranos. Critics loved its unfailingly beautiful cinematography and direction by incredible filmmakers. Audiences appreciated the show's unique setting and the beautiful vistas associated with the on-location Albuquerque shoots. And we couldn't get enough of the absurdly tight plotting that balanced surreal twists of fortune and the capers of hard-boiled criminals with equal care.

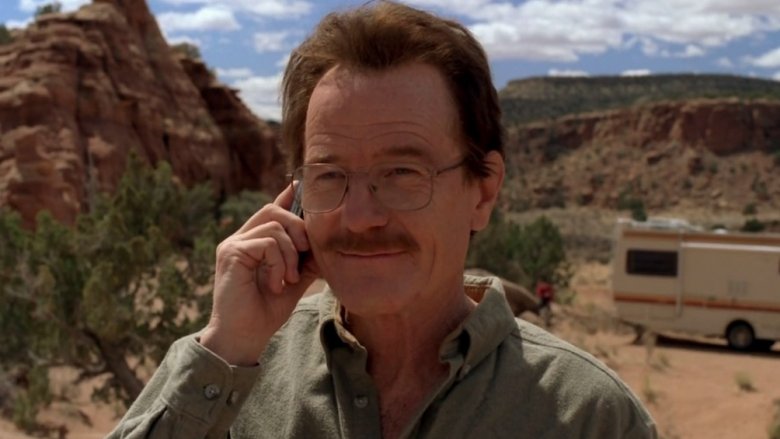

But mostly, Breaking Bad is one of the best shows ever made thanks to the character study of Walter White, a chemistry teacher with cancer who decides to cook meth to provide for his family. Brilliantly embodied by Bryan Cranston, Breaking Bad follows Mr. White over five seasons of insane adventures, all the way to an ending that still captivates fans to this day. It's an ending that completes the larger arc of the show while remaining ambiguous enough to demand plenty of interpretations. If you need a helping hand to understand that final episode of Breaking Bad, well then, let's cook.

What if Mr. Chips became Scarface?

Creator Vince Gilligan had one of the best high-concept hooks for Breaking Bad that any show has ever had. As Gilligan put it, "This is a story about a man who transforms himself from Mr. Chips into Scarface." Gilligan's expanded on that basic hook in interviews since, telling The Guardian, "I wondered why someone like us, which is to say a basically law-abiding citizen, would suddenly do such a thing. Why would someone make such a radical change in their lives if they were basically a good person, a non-criminal?" In other words, Gilligan wanted to tell the tale of a good dude who, "through sheer force of will," decides to break bad.

Where you start in a story is just as important as where you end. Walter White starts off as a timid chemistry teacher and ends the show as an infamous meth kingpin. But the subtext of that journey is that Mr. White wasn't always so kind and considerate. There are plenty of clues seeded early on in the show that hint that maybe "Mr. Chips" always had the propensity to be petty, vindictive, and violent.

What if Mr. Chips was already Scarface?

The appeal of Breaking Bad is pretty simple because it asks a question we've all probably wondered at least once. How far would a regular person go, what moral lines would they cross, if they knew they were dying and had to provide for their family? However, by episode five of the show, it's pretty obvious that's just a thin justification for wanton lust for power and petty pride that Mr. White already had.

In "Gray Matter," Walt and his wife attend a birthday party for Walt's former girlfriend and business partner, Gretchen Schwartz. They'd started a business together, and when Walt needed a buy-out, Gretchen married Elliott, their other business partner, and the two became absurdly rich, partly through innovations that Walt had invented. At the birthday party, Gretchen offers Walt a job, noting the company's "excellent health insurance" and acknowledging that it's only fair for him to have a place at the company that he co-created.

It's an act of pity, sure, but it's also a genuine offer that would do exactly what Walt is supposedly after—assure that his cancer doesn't bankrupt his family. Even better, he doesn't have to cook and sell meth and murder criminal rivals. Walt turns down the offer angrily and makes a huge scene as he leaves. He can't stand to accept pity, and he doesn't want to build a good life for his family if he's not the one who truly created it. It's about pride, not his family.

In Breaking Bad, Walter White just keeps reacting

In many ways, Breaking Bad is about the American dream, the idea that if you do good work, then the people in charge will see your value and reward you for your skills. Of course, most people would prefer their paychecks come from legitimate bosses and not various criminal drug lords in the crystal meth trade. Not so for Walt. After all, the longer he stays in the game, the higher he rises. But the higher he rises, it gets harder and harder for him to argue that he's just leaving a nest egg for his family.

As he rises from a simple meth cook to the big boss, Walt is given plenty of options to retire. By the time he's working for Gus Fring, he's about as close to a mainstream chemistry position as he's ever likely to get, with the added bonus of an absurd amount of money. It all blows up, of course, partly due to Walt's loyalty to Jesse Pinkman, and partly due to Walt's continuing belief that he can do better than Gus. When Gus is dead, Walt makes even more money, and he's even given the option to leave the business forever by selling some of his chemical components to a rival gang. Instead, he tells Jesse the truth, that the meth business is all he has left, and that he wants to build an empire to make up for his earlier loss of Gray Matter.

Do we feel sympathy for Walter?

Walt is the villain of Breaking Bad. That's not a hot take. It's the undeniable subtext (or even the actual text) of the show. By season five, he's poisoned a child, covered up the actual murder of another child, and is working with a white supremacist gang. It's about as clear as it can possibly be that Walt is deeply, morally broken. The entire show is extraordinarily explicit in just how many casualties Walt leaves in his wake while he pursues his own agendas. When he watches Jane choke to death without intervening, the fallout of her death leads to an entire passenger plane exploding over Albuquerque. This man has a bigger body count than anybody else in the show.

And of course, his job as a crystal meth cook isn't exactly helping anybody except himself. We've all seen examples of what horrific damage this drug inflicts on people. Walt is like a cancer, spreading every manner of depravity into Albuquerque. To make things even worse, his cancer goes into remission early on in the show. Sure, it comes back eventually, but the loose justification for his actions—that he'll be dead soon and needs to leave something to his family—is patently untrue for most of the show.

It's not exactly business as usual on Breaking Bad

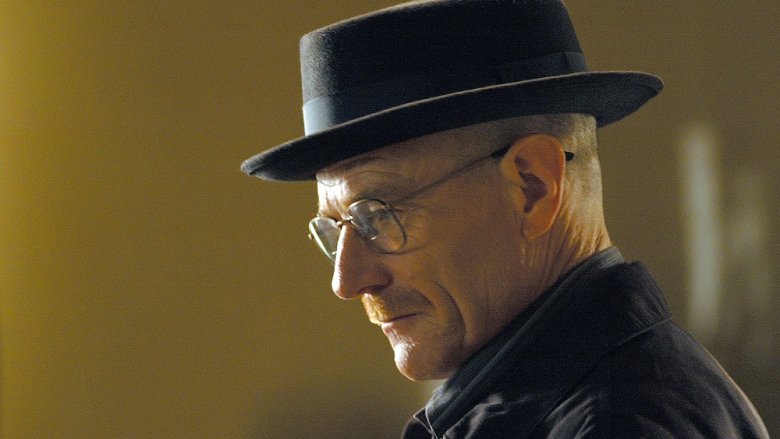

Walt's not just a bad guy in the moral sense. He's also clearly unhinged beyond what we see of other successful criminals in the show. Walt's undeniably smarter than your average meth cook, but his pride and open greed handicaps him as an effective crime boss. Compare him to Gus Fring, the most successful version of what Walt clearly aspires to be. He's ostensibly a family man (although there's never proof that his "family" actually exists), and he's deeply connected to public life. He's a respected businessman, insanely rich, and feared by his rivals. He's also a man of his word and usually pretty loyal to his employees. After all, he's earned the respect of Mike, a man who basically bleeds professionalism.

Walt, meanwhile, is constantly shortsighted and prideful. He kills Mike just because Mike mocked him. He murders Fring's old employees after they're sent to prison because it's cheaper to kill them than to keep paying for their silence. Even his loyalty to Jesse (arguably one of Walt's few redeeming qualities) is off and on, and he often manipulates his poor assistant for his own ends. Walt isn't just a villain...he's a monster.

Ozymandias changes everything on Breaking Bad

So we've spent a lot of time talking about Walt, but what does the actual ending of Breaking Bad mean? Well, first we need to specify which ending we're talking about. Each of the final three episodes—"Ozymandias," "Granite State," and "Felina"—can function as a kind of ending for the show. In the case of "Ozymandias," it's a poetic, circular ending. Walt betrays Jesse completely by giving his former partner up to the white supremacists he's been working with (Mr. White working with white supremacists, get it?). Worse still, he admits to Jesse that he watched Jane die and did nothing.

But even before handing Jesse over to the Nazis, Walt is indirectly responsible for getting Hank, his DEA brother-in-law, killed. And then Walt has to watch as Uncle Jack and his white supremacist gang take away all his earnings, except one single barrel of cash. Walt then has to roll the barrel back towards civilization, passing by the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode.

When he tries to convince his family to flee with him, his wife and son attack him, and Walt kidnaps his infant daughter. It's all of Walt's lies laid bare. He chose an empire over his family, and like a certain Shelley poem says, no empire lasts forever. Walt has the money to flee into a kind of witness protection program for criminals, but he's giving up the family that he pretended to do so much for.

Granite State gives Walt a blank slate

If "Ozymandias" is the "realistic" end to Walt's journey, then "Granite State" is a fitting punishment for the former meth kingpin. Walt ends up in a remote cabin where his only company, Ed "the Disappearer", comes by just once a month to drop off supplies. Even in the kind of purgatory that Walt lives in, he's still not free of his cancer, and he's constantly waiting for Ed to return with chemotherapy drugs. It's a fitting punishment for a man who pretended to do everything he did out of loyalty and filial piety. Walt is so lonely that he ends up paying Ed thousands of dollars just for an extra hour of his time. He's alive and rich but all alone. Much like the characters of a different AMC show, Walt is basically the Walking Dead.

The only thing that brings him out of his mountain retreat is the possibility of passing on his ill-gotten gains to his family. Walt literally tries to buy his way back into his son's affections, and of course, it doesn't work. However, he's given one last goal when he sees Gretchen and Elliott on television, downplaying Walt's contributions to Gray Matter Technologies. It's reasonable that they would. After all, it's not exactly good for a company's stock to have a co-founder become a murderous drug kingpin. Walt, unsurprisingly, does not see their side of things. Instead, he thinks they're disrespecting him by not giving him the credit for what he's earned. So naturally, Walt decides it's time to set things right.

Felina is Breaking Bad's fantasy finale episode

"Felina," the finale episode of Breaking Bad, is basically a victory lap for Walt. He gets to accomplish everything that he left his mountain retreat to do. He threatens Gretchen and Elliott into giving all of his money to his family under the guise of a charitable donation. He kills all of the white supremacists that stole his blue meth recipe. Walt frees Jesse from slavery, and he even gets a kind of closure with Skyler and his infant daughter.

Plus, he poisons Lydia with a whole lot of ricin, and he successfully evades the police all the way to the end. Even when he dies, it's on his own terms. He's not rotting of cancer but dying in the arms of his true love—the chemistry lab that produces his blue meth. Walt is infamous, which as we know from The Three Amigos, is when you're more than famous. It's almost a fantasy of Walt's ideal ending, and there are plenty of bizarre coincidences that would seem to back up that reading. How many actual, real people keep their car keys in the sun visor for anyone to find?

Felina is a monster movie where we follow the monster

"Felina" might be Walt's fantasy, but it's everyone else's nightmare. Throughout the episode, Walt is a monstrous presence. He moves through scenes like a horror movie slasher. When he talks to Skyler, he appears like a ghost—the scene is even blocked like a jump scare. When he brags to Lydia about how she's dead by his hand, it's a moment that wouldn't be out of place in a Final Destination movie. Walt gets his victory lap in the final episode, but it's only because he's chasing his enemies around the track.

Even when Jesse escapes the white supremacist compound, finally free of Walt and his vindictive torturers, he lets out a guttural scream straight from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. If there's anyone in the show that knows what kind of monster Walt was, it's Jesse. When he drives out of the show, it's as viscerally satisfying as seeing the final girl in a horror movie survive the killer. As for Walt, most monster movies end with the monster dead (before a last-minute revival), so it's fitting when Walt finally bites the dust.

In Breaking Bad's ending, lies become the truth

Walt starts Breaking Bad by telling his family that he loves them, and that everything he did was for their sake. He ends the show hobbling out to the meth shed to be with what he truly loves—a meth lab. It's clear (even more so than when he admitted to Skyler that he did it for himself) that he was never really Mr. Chips. Whatever falling out happened between him and his partners before the show started was a symptom of something deeper. Walt's cancer was just an excuse for him to be the power-hungry villain he'd always wanted to be. As Vince Gilligan once put it, "We always say in the writers' room, if Walter White has a true superpower, it's not his knowledge of chemistry or his intellect, it's his ability to lie to himself. He is the world's greatest liar."

Walt lied to himself for so long that he believed his own lies for most of the show. He lied to the audience, too. How much you want to believe that Walt was a good man is dependent on how much you want to believe his lies. Was he a good man who "broke bad," or was he always a twisted monster who finally got the excuse to behave like Scarface? We're leaning toward the latter.