These Things Happen In Every Single Pixar Movie

Pixar movies are some of the greatest films ever made, animated or otherwise, and the reason why is clear: Everyone involved spends about five years making every last moment as good as possible. Across 21 films, there have been only a handful of duds, and to be clear, a dud by Pixar's standards is still a solid movie by any other metric.

However, because roughly the same group of people keeps making these movies, Pixar has developed what you might call a strong house style. Many of these films feature hidden worlds full of strange creatures that nonetheless behave like modern humans. Most feature a fall from grace and a quest for redemption. Also, they're pretty much all about death, in one way or another.

Of course, the reason Pixar keeps telling these same types of stories is because they work. And presumably, they'll just keep making these movies forever, and so in the year 2050, when a family of estranged amoebas learns how to communicate, when two passing asteroids fall in love, or when a depressed jacket becomes friends with a sassy pair of bluejeans, you'll be able to understand how we got here. Here's your guide to the things that happen in every Pixar movie.

What if 'fill in the blank' had feelings?

Ever since they made a short about two lamps playing with a ball all the way back in 1986, Pixar has had a talent for bringing inanimate things to life. Their first feature film, Toy Story, solidified their love of the inhuman as a core element of the studio's identity.

Pixar's formula for selecting a premise for their movies seems to be taking something that's not typically thought of as being "a person," and treating it as though it was a human being, with a full range of complex and messy emotions. What if toys had feelings? What if bugs had feelings? What if monsters had feelings? Whether it's fish, cars, robots, dinosaurs, or dead people, the question about "what if 'fill in the blank' had feelings?" lies at the heart of most Pixar films.

This is a stark contrast to Disney's way of doing things, which is to take a preexisting fairy tale, add songs, cut out all the weird stuff, and give it a happy ending. Rather than taking a classic story you already know, Pixar tends to take things we don't typically think of as being story-worthy, and then shows us that every story is worth telling, if you know how to tell it well. This particular line of thought eventually reached its logical conclusion with 2015's Inside Out, which finally dared to ask the question, "What if feelings had feelings?"

Pixar characters have it coming

Pixar films begin with a protagonist who's relatively happy and in control of their particular universe ... except for one problem. Like the heroes of Greek tragedy, Pixar protagonists have a tragic flaw, and from the moment the film opens, this flaw is secretly eating away at them, keeping them and the people around them from being as happy as they could be.

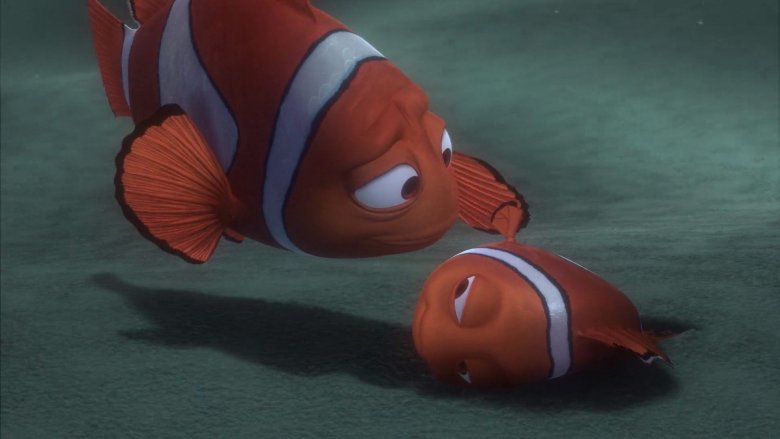

Marlin and his son Nemo clearly love each other, but Marlin is also obsessed with keeping Nemo safe to an obsessive degree. Joy does a relatively good job of keeping Riley emotionally healthy, but she can't stand it whenever Riley experiences any emotion other than happiness. Woody is a good leader to his fellow toys, but he's also secretly terrified that one day he'll be replaced by someone newer and cooler.

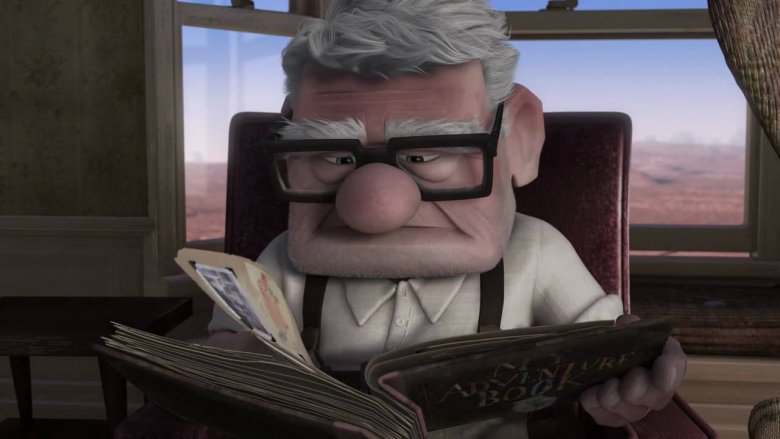

Eventually, this flaw causes our hero to make a big mistake. Carl's need to hold onto Ellie's memory leads to him accidentally injuring a man who's in danger of destroying his mailbox. Flik's desire to show off his inventions leads to him destroying the food that's meant for the grasshoppers. Mr. Incredible's massive ego and poor communication skills lead to him telling Buddy, "I work alone." This one mistake will eventually see the protagonist ending up in their own personal hell, and it will be a hell entirely of their own making. Whatever the big problem of the movie ends up being, it will be our hero's own fault.

A hidden world revealed

In a presentation by Pixar animator Dave Mullins, he outlined a list of ingredients that he believes are the reason why Pixar movies are so darn good. One element that he listed was "setting," saying, "The film needs to transport the viewers to a place that is exciting and new." Another element he listed was "animation." He said that an animated film "must call for being animated, and use animation's full potential." These two elements lead to Pixar choosing to set their stories in worlds that audiences have never seen before, and in some cases, could never see.

Sometimes these worlds are new to the characters in the story, and sometimes they're just new to us, but regardless, Pixar takes previously hidden worlds and shows them to us for the first time. In our modern era, where just about inch of the Earth has been mapped by satellites, that doesn't leave a lot of new places left to set a story. Perhaps this is why the settings of Pixar movies include the inside of a teenager's mind, the bottom of the ocean, a world where dinosaurs never died out, and the world where monsters come from. Pixar wants to show something you've never seen before, and they want to take you to the places that live action can't take you.

A curmudgeon learns empathy

There's a certain type of character that keeps on showing up in Pixar movie after Pixar movie. They're confident, they're competent, and they secretly hate everyone around them. We're talking about Woody, Marlin, Carl Fredrickson, Merida, Joy, Lightning McQueen, and Mr. Incredible. Sure, they might be the best at what they do, but at the end of the day, they're utterly alone, and since they're still just one person, there are certain things they'll never be able to accomplish until they learn to let someone else in.

At the beginning of the movie, the fact that our hero is a big jerk is more or less invisible, because no one is challenging them. Then this sourpuss meet someone who, at first, doesn't seem to be as competent as they are, someone they totally dismiss. This is Buzz Lightyear, Dory, Russell, Queen Elinor, Sadness, the denizens of Radiator Springs, and Mr. Incredible's entire family. Sure, they're nice and all, but they don't really get it. As Marlin or Mr. Incredible might put it, "I'm the only one who can do this, and I have to do it alone."

As you might imagine, by the end of the movie, after they fail time and again, our hero finally learns the hard way that they can't do it all by themselves. However, this isn't a loss in the end, because once they learn to trust someone else, our hero discovers they can do more than they ever imagined with the help of their friends.

John Ratzenberger shows up in every single Pixar movie

Given that Pixar movies are among the most successful animated movies of all time, the studio could hire pretty much any big name actor they want by now. And even though they do indeed routinely stack their call sheet with Hollywood A-listers, they always save one spot for an old friend. In every Pixar film since the very beginning, at some point, some character is going to be voiced by John Ratzenberger.

Before working with Pixar, Ratzenberger was best known for playing postal worker Cliff Calvin on the sitcom Cheers. However, after he knocked it out of the park in his role as Hamm in Toy Story (and ended up being just a really nice guy to hang out with), Ratzenberger quickly became the studio's lucky charm.

Presumably, Pixar has just kept him locked up in a recording booth since 1995. How else would he have the time to play over a dozen different characters across 21 films, including a flea, a semitrailer, a yeti, a supervillain, a waiter, a school of fish, a skeleton, a construction worker, a velociraptor, and more? Andrew Stanton, director of Finding Nemo and WALL-E has said, "He's the ultimate Pixar character actor. ... Having him in every film is like our Hitchcock cameo."

We love listening for when Ratzenberger's highly recognizable voice is going to pop up in each new movie, but let's hope Pixar lets him out of the studio every once in a while so that he can at least see the sun.

The villains aren't so different from the heroes

Pixar movies don't always have a traditional antagonist, but whenever they need one, their writers show that they really know how to make a memorable villain. Syndrome is the perfect archetypal supervillain, and the reveal of Ernesto de la Cruz's bad side is thoroughly chilling. Charles Muntz and his army of talking dogs make for some hilariously awesome antagonists, and Lots-o'-Huggin' Bear is right up there with the Joker as one of the most haunting villains in cinema history. So what's the secret to Pixar's villains all being so great?

What every Pixar villain has in common is that, at some point, they were very much a hero. Much like our curmudgeonly protagonist, they had a lesson they needed to learn. But where our hero is still on the fence about it, the villain outright rejected the truth long ago, and instead embraced their fatal flaw. Syndrome became consumed with revenge after being rejected by Mr. Incredible, Ernesto de la Cruz started valuing music more than his family, Charles Muntz kept chasing adventure and never learned to love "the boring stuff," and Lotso stopped believing that the love between children and toys is real.

What makes these villains so good is that, down to their last moments, they're so close to being good guys, but at the same time, they are definitively not. Often they're downright murderous. Sadly, these bad guys are usually long past saving, but meeting them is just the wake-up call our stubborn heroes need to finally change their ways.

There's always a whiff of death

Given that they're ostensibly kids movies, you'd be surprised by how many Pixar movies there are that deal with death in a pretty central way. Mortality, mourning, and the inevitable passing of time are all at the heart of films like Toy Story 3, Up, Inside Out, and Coco. Even The Incredibles has a shockingly high body count.

Pixar characters regularly lose everything they love, either temporarily or permanently, and have to learn to accept that loss and keep going. For a few hours, Mr. Incredible thinks his family has been killed by Syndrome. Marlin loses his wife and all his kids except one at the start of Finding Nemo, and for a bit towards the end, he thinks Nemo has died as well. And for a minute, even Sully thinks that Boo was crushed into a cube. If you're a Pixar protagonist, you usually have to mourn at least one family member or friend before you get your happy ending. R.I.P. Bing Bong.

Screenwriting guru Blake Snyder referred to this beat in a screenplay, when the hero is at their lowest point, as the "all is lost" moment. It occurs right before the climax, when the hero believes they have lost everything forever. In this moment, he says that if you don't want the character to die, you should at least insert some sort imagery that evokes death, or as he puts it, a "whiff of death." Snyder would be proud of Pixar, because their movies reek of it.

We cry our eyes out during every Pixar movie

At some point towards the end of every Pixar movie, there's "that moment." It comes out of nowhere and hits like a ton of bricks. Then, no matter how many times we've seen it, we suddenly get a little dust in our eyes. Anton Ego eats Remy's ratatouille and finds himself transported back to a childhood memory. Captain B. McCrea gets out his chair for the first time to take control of the Axiom. The Incredibles finally stand together as a superhero team. Carl opens Ellie's scrapbook and learns that she died without regret.

It isn't obvious until you re-watch the film, but often times, the entire movie has been constructed to make this one moment possible. We stated earlier that Pixar protagonists have a fatal flaw, a harmful lie they cling to for comfort (except Wall-E, he's perfect). The moment when you cry the most in any Pixar film is when the main character finally discards this old lie that's making them miserable, and learns to see the world around them as it truly is for the first time. Marlin discovers that Nemo can thrive all on his own. Buzz stops trying to be a Space Ranger and embraces the simple joy of being a toy. Carl stops believing that "adventure is out there" and realizes that every day is an adventure when you're with someone you love. Oh gosh, we're getting misty-eyed already.

Easter eggs from upcoming films

Pixar movies are full of Easter eggs. The Pizza Planet truck from Toy Story appears at least once in pretty much every film. The serial number A113 is everywhere, as a nod to the room number for the animation department at the California Institute of the Arts. Possibly the most intriguing recurring element is a hint towards what's coming next. At some point in every movie after the first Toy Story, an object from an upcoming film will be lying around somewhere, oftentimes depicting a character that audiences don't even know the name of yet.

If we listed them all, we'd be here all day, but here's a few to give you an idea. In Monsters, Inc., there are numerous instances of Nemo toys lying around. In Finding Nemo, a boy in the dentist's office is reading a Mr. Incredible comic book. Carl Fredricksen's walking stick, complete with tennis ball feet, appears twice in WALL-E. In Up, a little girl can be seen with a Lots-o'-Huggin' Bear. The witch's hut in Brave has a wood-carving of Sully, as a nod to Monsters University. In Cars 3, Ernesto de La Cruz's guitar is hanging on the wall behind a band playing in a bar. And finally, in Incredibles 2, one of Jack-Jack's toys is Duke Caboom from Toy Story 4.

Next time you watch the newest Pixar movie, be on the lookout for an object that seems out of place. It might just be a sneak preview of what's to come.

The sequel will be more 'woke' than the first

Despite their many exemplary qualities, early Pixar, much like a Pixar protagonist, had a tragic flaw. For their first 12 movies, they didn't have a single female or nonwhite protagonist. Even when their hero was a toy or a race car, they were consistently voiced by white men, and they were "coded" as white men.

But lately, Pixar has been getting better about this. Brave and Inside Out have female protagonists, and Coco has a Latino protagonist. Another big way that they've been giving marginalized people more spotlight time is by changing things up with their sequels.

There was a time during the writing of Monsters University when it just wasn't working. The story kept wanting to be about Mike, but he'd just been a supporting character in the first film. Eventually, the writers stopped fighting it, and the movie improved dramatically. Ever since then, Pixar's formula for sequels has been to take an underserved character from the first movie and make them the star. Movies like Finding Dory, Incredibles 2, and Toy Story 4 take the formerly sidelined characters of Dory, Elastigirl, and Bo Peep, and then give their stories the focus they deserve.

Thankfully, it seems like Pixar finally had a "Pixar moment" of its own, and fixed its own tragic flaw, when the creators finally asked the question, "What if someone other than a white dude had feelings?"