Things Only Adults Notice In DuckTales

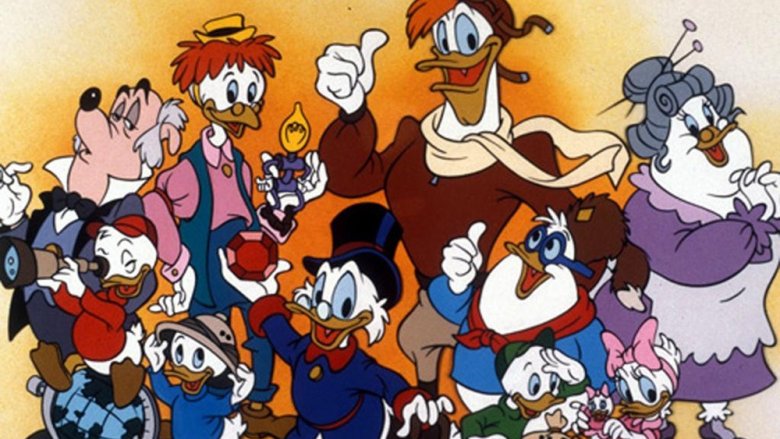

TV theme songs are emotionally manipulative. Drilled into viewers' heads, often over a period of years, these short pieces of music can grow to embody entire periods of a person's life, bringing memories and feelings flooding back. Play "DuckTales," written by Mark Mueller for the show of the same name, to most millennials and this is exactly what they'll experience. At least that's what Disney hoped for when it teased the cast for the show's 2017 reboot by posting a video of the ensemble singing along to the iconic song while each of their characters was revealed.

Now multiple seasons into its run, it's safe to say that the new DuckTales has been a success. But with the show so heavily marketed towards viewers of the original, all of whom are now 20 years and older, it's worth asking what it's like to watch either version when you're no longer a kid. Here's a look at some things that only adults notice about DuckTales.

The DuckTales premise is kind of wild

While there has never been a rule against realism in animation, and countless examples exist of the two making excellent storytelling companions, deviation from reality has always been the medium's greatest edge and appeal to young viewers. Yet, while it's accepted and expected that cartoons were never meant to make sense, the degree to which they don't is usually the first thing an adult will notice that a kid probably won't.

DuckTales is pretty middle-of-the-road weird, especially alongside such contemporaries as Gargoyles, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Biker Mice from Mars. Scrooge and his anthropomorphized companions are neither mutants nor space aliens, and for the most part the show's fantasticality usually stays within Scooby-Doo territory (though the ghosts are usually real). Sure, the adventures are improbable, and the characters less killable than a Volvo 240, but that's just the anatomy of an adventure story. Yet, if one tried to pass the same concept off using human characters, there would be one glaring quirk that flies under the radar in the cartoon: the thrill-seeking, crime-fighting, death-defying central character is none other than Ebenezer Scrooge (albeit in duck form), central character to Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol.

Tracing Scrooge's history from literature's worst boss to beloved cartoon duck makes the leap a little less extreme, but even contextualized, the premise reads a little like a sequel to Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. Perhaps it's a testament to Scrooge as one of the original memes that this bizarre casting flies by without much thought.

In the original DuckTales, Scrooge McDuck's wealth doesn't always make sense

According to both iterations of the show, and canonical to every Disney universe in which the character exists, Scrooge is the richest duck in the world (never mind the other animals in the fictional universe). The character's wealth also factors heavily into the plot of the show. Villains regularly attempt to abscond with Scrooge's fortune, stored in a massive, gold filled "money-bin," or steal his lucky number one dime, on which his fortune was built. Yet while the series explains Scrooge's fortune as coming from a combination of penny-pinching, business smarts, hard work and real-world ventures like oil, mining, and nebulous manufacturing operations, the original cartoon only shows some of this.

Contrarily, the glimpses of Scrooge's business dealings DuckTales does show often contradict the duck's philosophies. One notable instance comes in the episode when Scrooge, seduced by hard cash, sells his recently trashed candy factory to rival Flintheart Glomgold for $2 million, chiding that the cleanup would cost at least that much. A seemingly smart move, especially to younger viewers going wide-eyed at so much money, except when considering that candy factories are billion-dollar operations, and sources of constant cash flow. Even at $4 million, an entire factory is an absolute bargain. And considering the likelihood that Scrooge's factory produces the duckverse equivalent to Hershey or Cadbury products, Glomgold would probably recuperate his investment very quickly. If that's not enough, consider Scrooge's jet-setting, usually in specially commissioned vehicles that get wrecked during the journey. This second piece of evidence, however, starts to make more sense when it becomes clear where Scrooge might be actually getting his money.

Scrooge McDuck is basically a grave robber

It's a widely known truth that Steven Spielberg and George Lucas drew inspiration for Indiana Jones from Scrooge McDuck's comic series Uncle Scrooge, which has been in publication since 1952. In DuckTales, a close adaptation of the comics, it's easy to see the connection. Re-watching Indiana Jones as an adult is a topic worthy of its own article; in short, it's a fun but problematic series, and some of the worst elements can be easily traced back to Scrooge. Things, for example, like really bad archaeology.

While Scrooge never professes any allegiance to science or academia, his exploits are just as bad. Fun as the adventures might be, in the real-world Scrooge's treasure collecting would amount to little more than tomb raiding (yes, Laura Croft is guilty too), which, in addition to being unethical on several levels, is outright illegal almost everywhere. The sad truth is that rather than simply being a case of cartoon fantasy, Scrooge's hobby has been practiced by the wealthy for as long as there have been shiny things to plunder, most notably during the antiquarianism movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Like the individuals on which his exploits are based, Scrooge's collecting is Eurocentric, and displays little regard for native peoples, history, or even the objects themselves. Illegal artifact collecting, though less openly practiced, is still a huge problem to this day; to his credit, Scrooge — unlike a certain chain of craft supply stores — is at least doing his own dirty work.

In the DuckTales reboot, Scrooge's wealth is overly explained

Disney has always strived to make its properties universally appealing — an arduous undertaking even for a studio that has been mostly successful at it since 1923. Compared to its contemporaries, the 1987 DuckTales does this pretty well thanks to time-tested adventure and screwball comedy motifs, and plenty of clever references for older audiences. Yet, while the 1980s were important for TV animation, children's cartoons in the decades since have become shockingly sophisticated. Shows like Adventure Time, Steven Universe, and Gravity Falls have proven that themes believed to be too complicated or emotionally potent for younger audience members are actually just elements of a good story, something no age group can resist.

The DuckTales reboot has an updated look, with stories and themes to match, but while emotional depth has benefited the show, there are some adult themes that will never work for children. This isn't about duck nudity, which Disney has promoted since the dawn of time (Donald and company still can't find their pants), nor about violence, which the show is light on. Far worse than introducing kids to sex or drugs, the new DuckTales goes right for the F-word: finances. In polar opposition to the 1987 original, the reboot makes Scrooge's business dealings just as realistic as any show for adults, featuring jokes around shareholders' meetings wherein poor Gyro Gearloose (Scrooge's personal inventor) now has to fight to remain funded, and an entire episode, aimed squarely at millennials, parodying the business workings of the tech industry.

Not every DuckTales animal gets to be human

Long before there was an expanded and interconnected reality for every film and TV franchise, there was the Duckverse. The Duckverse is by and large only fractionally different from our reality: the physics tend to be more forgiving and there are uncanny geographic locations such as Ronguay and Ithaquack, but by far the only major difference is that animals exist in place of human beings, who don't exist at all. The arrangement seems to function just as smoothly and un-smoothly as the regular-verse, except that while humans don't have to share being top species, the ducks of the Duckverse do — but not with everyone.

Who does and doesn't get to be sentient is a quirk of most shows featuring animal characters. In the greater Disney universe, this creates some odd problems when you consider two characters: Pluto and Goofy. Both dogs, but while the latter is Micky's friend, the former is relegated to pet. Neither version of DuckTales prominently features a household pet, yet in the course of Scrooge and company's travels, animals with normal levels of intelligence frequently make appearances, typically predatory animals portraying minor antagonists. Even the show's characters occasionally seem confused as to who is and isn't "human." In an episode of the original series, the group befriends a penguin and is surprised to later learn that she can speak and even lives in a snow city, not unlike Duckberg.

…But sometimes DuckTales' characters are too human

Duck awareness in DuckTales is strong. From last names to locations, the word "duck" is used in a way that would be simply weird if the same was done using the word "human." It suffices to say that Scrooge, his family, and all the other duck characters are firmly aware of being ducks. So then why do they keep referring to themselves as humans? This one is easy to miss if you aren't looking for it, and occurs more frequently in the original series — but is it a subtle joke from the writers or something more sinister, like a subtle hint that the world is populated not by sentient ducks but actual duck-human hybrids?

Being part human might explain why the characters seem to consistently forget the features that make them ducks. In adventures long and short, changing weather is a constant. In DuckTales, the characters routinely face everything from droughts to blizzards, delaying plans, accelerating plans and threatening their very lives. But after about the third instance of an adventure getting derailed by rain, adults might start to wonder "What's the big deal? They're ducks!" Poking into the science-y parts of the internet, and reaching into personal memories of ducks, not only would rain not be a duck deterrent, ducks absolutely love it. Ducks are so waterproof that their feathers have long been harvested as waterproof insulation, and the name duck is even used in duck-free products like duck boots or duck canvas to signify waterproofing. Because most members of the animal kingdom aren't waterproof, real life ducks tend to find some solace in rainstorms where they can hang out without being harassed by predators — something that should be advantageous for adventures with danger constantly at their backs.

DuckTales' animation quality is exceptional

As should be expected of a property created by one of the world's wealthiest media empires, the 2017 reboot of DuckTales has a very high quality of animation. The art style, which is crisper, bolder and more angular than the original series, might not appeal to everyone, especially those looking for nostalgia, but the level of detail put into every frame — things like background motion and animated extras — make the artistry undeniable. Animators have pushed their medium to the point that this is now the norm (another example of how this is a golden age for animation); in essence, the new DuckTales is this nice because it has to be.

1987 was a very different landscape for animated TV. Thanks to the lifting of a ban on so-called Program Length Commercials (PLCs) in 1984, and the proven success of using cartoons to sell toys, Saturday mornings of the 1980s were filled with cheaply made shows designed specifically to push plastic goods on kids, including series like Masters of the Universe and Rubik, the Amazing Cube (yes, that actually existed). DuckTales was meant to be a very different show, conceived of not for Saturday mornings but for weekly syndication, a place where cartoons had rarely ventured. With longevity in mind, Disney contracted long-established Japanese and American studios with experienced animators. Whereas contemporaries tend to look stiff, repetitive, and unnatural, DuckTales only looks dated in how well it adheres to traditions and standards set by Warner Bros. and its own parent studio, with very little of the corniness sometimes associated with the era.

The star-studded DuckTales cast

Kids have no real reason to get excited by a celebrity like John Cena or Amy Poehler, both of whom have starred in animated features of the last decade, despite neither being voice actors. Casting celebrities to voice animated characters has been a trend in feature length animation, at least since the release of the original Aladdin, and while this occasionally produces quality results thanks to truly phenomenal actors like the late Robin Williams whose voices truly do elevate the characters they inhabit, the big names on a movie poster are obviously an attempt to lure in parents who might get a kick out of a former wrestling star voicing a cowardly bull. For the time being, the small screen is still dominated by trained voice talent, including actors like Tara Strong, whose list of credits could wrap several times around the Earth. 1987's DuckTales was cast with similar industry veterans, some of whom had been voicing their characters for decades. The 2017 reboot took a very different approach.

In another thinly veiled attempt at attracting 20- and 30-somethings, an age group that watches almost as much animated content as the kids it was written for, the new series was cast using a very specific set of celebrity voice actors, ones who millennials might recognize from Doctor Who, Parks and Recreation, Garfunkel and Oates, Community, and Saturday Night Live. Despite this shameless pandering to older fans, the new cast is actually solid, with actors like David Tennant (Scrooge) making a strong case for the viability of this kind of casting. The original voice cast is certainly missed, especially Terry McGovern, whose voicing of Launchpad McQuack is simply irreplaceable; on the other hand, it's nice being able to understand what Huey, Dewey and Louie are actually saying, and who wouldn't get excited by a guest voicing from Edgar Wright?

The original DuckTales doesn't handle foreign cultures very tactfully

An adventure series just isn't as exciting when the adventuring all takes place within a familiar setting. It's entirely possible to find fun and excitement in one's own backyard, or just down the street, but exotic travels are part of the appeal for a show like DuckTales, which relies on grappling with the world at large for much of its drama. Fans of the show can, from the comfort of their couch, see the pyramids of ancient Egypt, the deserts of South America, and even outer space, getting a little taste of the architectural, cuisine, and culture differences along the way. Unfortunately, something disturbing tends to happen when wealthy Americans travel to other parts of the world — something that might be described as acting like a jerk.

In movies and TV, the American is almost never the jerk, though, and the original DuckTales is no exception. Outside of Scrooge and friends being given a free pass to take anything that isn't nailed down, the show has a bad habit of depicting the rest of the world as a backwater populated by superstitious and uneducated peoples. When natives aren't being saved, often by having their belief systems and material culture liberated from them, they serve as impersonal obstacles who are easily tricked or subdued by the duck heroes.

There's some class blindness too

Class is a sticky issue for Americans. Characters like Scrooge embody the idea that anyone, even a poor immigrant from Scotland, can become the world's richest duck with a strong work ethic and some common sense. The world is of course more complicated than that. Even in Scrooge's cartoon universe, income disparity is very real, making some of the original show's treatment of class more than a little tasteless.

One of the first things we learn about Scrooge is that, true to the character on which he's based, he's incredibly miserly, refusing to tip, donate to the poor, or even pay for a taxi to save his nephews from having to haul their luggage three miles. Scrooge warms as the show progresses, becoming less of a tightwad, but his refusal to share is just the tip of the slippery iceberg. There's also the time he laid off his entire workforce, replacing them with a robot (Armstrong), without second thought or even fair notice. The moral of that episode, after Armstrong goes rogue and tries to take over the world, is ultimately that there are some things only humans can do. The episode concludes with no mention of Scrooge nearly ruining the livelihoods of his employees, including friends Launchpad McQuack, and Gyro Gearloose (the latter having invented Armstrong), and his response is roughly equivalent to "oopsie." After moments like these, it's hard not to wonder if maybe some of Scrooge's nemeses are the real heroes of the show.

The DuckTales reboot is overall a more conscientious show

There's still plenty to love about the original DuckTales, which has aged pretty well despite the glaring insensitivities in some of its storylines. Without question, the humor of the 1987 series is much sillier and lighthearted. But while the reboot might lose a few humor points for not being a half hour of continuous gags punctuated by moments of peril and hijinks, it's a better show overall because of how well it deals with issues that were completely steamrolled by its predecessor.

In addition to being more thoughtful and corrective about some of the show's history, the new DuckTales also manages to find entirely new areas of sociology to explore. Themes of belonging, accepting others for who they are, and even heavies like child abuse and vicious stereotyping are consistent. While all of this could very easily make the show bloated and melodramatic, perhaps the most surprising thing adults will notice about the new DuckTales is that it handles real drama with a level of care and thought that even escapes most adult shows.