The Untold Truth Of Naruto

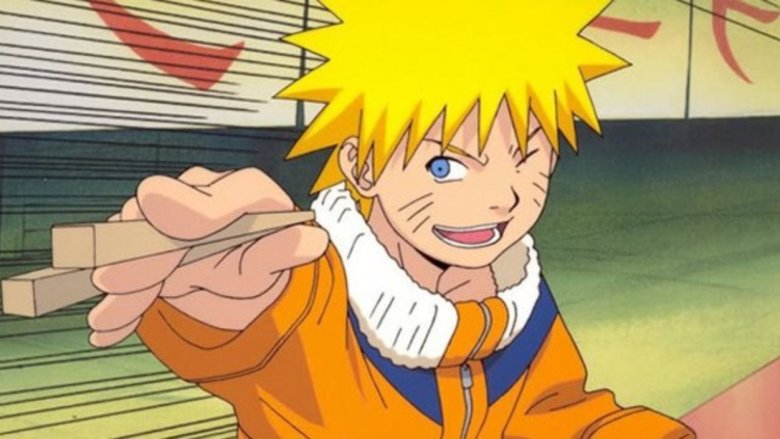

Late '90s manga-turned-anime Naruto is among the most recognizable media for teens in its native Japan as well as overseas, on par with predecessors like Dragon Ball. The tale of the plucky, orphaned ninja-in-training with a penchant for ramen and mischief hit the magazine racks of North American booksellers as part of VIZ Media's Shonen Jump in the early aughts, paving the way for a generation of readers to be indoctrinated into the wide world of manga and anime. Almost two decades later, it remains an early influence for many young people, as well as a series that lives on in the hearts of adults who recall wearing their very own Konoha leaf village headband to school every day with fondness.

Like so many great series, Naruto just has that special something that allows it to endure in a constantly shifting media landscape, appealing to readers and viewers time and time again. Behind the series, behind its determined protagonist, there are so many factors that help to keep fans coming back for more — factors that are worth exploring. This is the untold truth of Naruto.

Who created Naruto?

There would be no Naruto without creator Masashi Kishimoto, who has dedicated much of his career to this one series. As is often the case with Japanese comics creators, Kishimoto is both the writer and illustrator. He grew up extremely fond of manga and anime, reportedly shaming all his kindergarten classmates when they did not draw popular children's cartoon character Doraemon correctly. From there, he dove headfirst into an obsession with Akira Toriyama's genre-defining Dragon Ball; his interest was also piqued by Katsuhiro Otomo's cult classic manga and film Akira. In fact, Kishimoto later contributed to an art book of illustrations dedicated to Otomo's masterpiece.

As a student, Kishimoto was so focused on drawing that his academics fell to the wayside. Luckily for him, Naruto is the fourth best-selling manga of all time, so all that class time spent doodling may not have been time wasted. Tack on a very successful anime adaptation and scores of merchandise, and it's safe to say that Kishimoto followed the path that was right for him, no matter what society deemed was appropriate — not unlike his stubborn and silly protagonist.

Naruto spinoff media and merchandise

Shonen Jump is an excellent example of how to successfully monetize media. All of its most popular series go on to enjoy a second, third, or even fourth life, constantly being revitalized by a parade of tie-in media, products, and other gimmicks. Naruto is no exception. The series has, aside from its anime adaptation, 11 films, three official artbooks, 26 novels (15 written by Kishimoto), a collectible trading card game, and scores of the usual T-shirts, keychains, figures, and other consumer goods. Even Adidas has created a line of Naruto-inspired sneakers, following their Dragon Ball line and coinciding with Sketchers' second line of One Piece offerings. So despite the fact that the Naruto anime and manga have both been over for years, there is no end in sight to its money-making potential — which speaks volumes for its popularity among fans.

The Naruto run

Something that became readily apparent when Naruto was adapted into an anime was the unique way in which Naruto and his compatriots would run: leaning forward with their arms thrust behind them, their upper body rigid as they attempted to ace their various ninja training exercises. This run, simply referred to by fans as "the Naruto run," has become a sort of ongoing joke in the anime community — and on the internet at large. In 2017, fans in several cities organized Naruto runs, open to the public, where participants would run around like a Konoha ninja, preferably in cosplay. And in July 2019, the notorious Area 51 meme pivoted around the central idea that individuals participating in the "storm" on government-patrolled Area 51 would arrive on the scene performing the Naruto run. Seems unlikely that it'd help participants invade the base, but hey — if you're going to be detained by the government anyway, you might as well go out in style.

Behind the Naruto name

Naruto's two closest companions at the outset of the series, Sasuke and Sakura, have fairly straightforward Japanese names, but his is more unique. In Japan, an island country where fish is historically a large part of the diet, "naruto" or "narutomaki" refers to a type of processed fishcake, made to look like an "uzumaki," or spiral shape. For Japanese readers, the name "Naruto Uzumaki" is much sillier than most English-speaking readers will notice at first glance. This use of weird or food-related names is a staple of boys' manga, undoubtedly influenced by Akira Toriyama's Dragon Ball, which includes characters like Gohan ("rice") and Bulma ("buruma," or "bloomers"). Bleach, a peer of Naruto, has a main character named Ichigo, or "strawberry." Kishimoto keeps the spirit alive in the Naruto sequel Boruto, with a character named Sarada, a reference to the Japanese pronunciation of the English word "salad." There doesn't seem to be any deep, underlying reason for this trend other than that it's fun, and Toriyama set a precedent that his manga descendants couldn't help but emulate.

Naruto's catchphrase

Every comic book hero needs a catchphrase, and for the goofy Naruto, it's "dattebayo!" in Japanese. It translates to "believe it!" in the English dub, but "dattebayo" is actually a nonsense phrase with no real meaning.

Naruto comes by this weird verbal tic honestly. His mother, Kushina used the similarly nonsensical "dattebane" when riled. And Naruto's son, Boruto, would prove to be a chip off the old block with his own catchphrase, "Dattebasa!" Naruto's closest comrades also had their own frequent sayings at the start of the series. Sasuke would utter "usurakontachi" whenever he felt that Naruto was being particularly obtuse. This phrase loosely translates to "thin hammer," and Sasuke's tone and delivery solidify it as purely an insult. Sakura's phrase, "shannaro," also has no literal translation; instead, its meaning varies with each delivery. "Dattebayo" has often been cited as a reason that aspiring Japanese language learners should not blindly utilize subtitled anime as a resource. Nonsense phrases are not confined only to Naruto, and could prove confusing to someone who doesn't have adequate experience with the intricacies and nuances of the language.

Behind Naruto's nine-tailed fox spirit

Though Naruto has many modern elements, there is undoubtedly a huge link to Japan's past running throughout the series. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the presence of yokai. In Japanese, the term roughly translates to "mysterious phenomena," and encompasses a wide array of strange creatures, ghosts, mythical beings, and other elements of the inexplicable. The most obvious and visible yokai in Naruto is Kurama, the nine-tailed fox demon that destroyed Konoha many years ago and which lies dormant within the main character, waiting to emerge again. The villagers live in fear of this powerful beast, and thus Naruto himself is ostracized from society for most of his childhood. The nine-tailed fox is not a Kishimito invention. The fox, or kitsune, is revered in Japanese folklore, and the number of tails it has denotes its age, amount of power, and/or its wisdom. The best way to defeat the trickster fox is to remove all of its tails. Kurama is one of ten tailed beasts within the world of Naruto, and there are clear links between each of these demons and their traditional yokai counterparts.

How Naruto draws on myth and legend

Yokai are not the only legendary element of Kishimoto's tale. In fact, Naruto is heavily inspired by Japanese mythology, especially Shintoism, and even Confucian thought. For example, Sasuke's brother, Itachi, has techniques named after the Shinto deities Tsukiyomi, Amaterasu, and Susano-o. The proliferation of eye-related ninja techniques in the series also seems rooted in ancient ideas about magic, perhaps influenced by the tale of Tsukiyomi (the moon god) and Amaterasu (the sun goddess) being born from the eyes of the god Izanagi. And then there are academic arguments for the presence of Confucian values in manga aimed at a young boys' demographic, especially series like Naruto and Bleach. By including these philosophies subtly in popular media, Kishimoto helps Confucian thought continue to influence generation after generation without seeming like dry old history or complicated philosophy.

That's my ninja way!

Kids everywhere love the concept of ninja, though their historical counterparts are frequently misrepresented by modern interpretations. In Naruto, the young ninjas-in-training receive a lecture from their teacher Kakashi about how ninja techniques, or ninjutsu, work. The in-universe method relies on a channeling of a ninja's chakra, or internal energies, and the use of various hand motions referred to as "seals." The story relies heavily on folklore about ninja and shinobi, as opposed to historical fact. In truth, ninja were highly specialized spies, mercenaries, and assassins in feudal Japan. They faded out of existence around the 17th century, and later generations spun stories about these mysterious masked mercenaries as possessing supernatural stealth — basically, the type of ninja we are familiar with today. So while Naruto does spend a lot of time showing the ways in which Naruto and his peers train their bodies for stealth and action, it also plays into the idea of ninja possessing mystical — often genetically or supernaturally inherited — powers and abilities.

The music of Naruto

Pretty much any serious anime fan has their favorite anime opening and ending themes. It's a huge part of anime fandom for many viewers, and Naruto has the distinction of rearing a whole generation of young people who can't resist a peppy, fast-paced Japanese pop tune suitable to use as a soundtrack for your average gym workout. The bands Flow and Asian Kung-Fu Generation are particularly beloved among Naruto fans. Asian Kung-Fu Generation's song "Haruka Kanata" graced the show's second opening, providing a deep thrumming bass line to introduce a voice strained with determination, very appropriate to the story's protagonist and his quest to become the Hokage, or leader of his village. And while Flow provided several songs for the series, the most easily recognizable is probably "GO!!!," with its resounding chorus of "We are fighting dreamers!" in English. Both bands have gone on to do lots of work in anime, providing music for series like Bleach, Eureka Seven, and Fullmetal Alchemist.

From Naruto to Boruto

Though the Naruto manga and anime series both ended after many successful years, there's still story to tell. Naruto got married to Hinata and they had two kids, a son named Boruto and a daughter named Himawari. Boruto is the spitting image of his father, and his film and manga follow the exploits of his own ninja team and their training. Boruto's team consists of himself, Konohamaru Sarutobi (the old Hokage's grandson), and Sarada Uchiha (Sakura and Sasuke's daughter).

Boruto may seem like a cash grab to a lot of longtime fans, but there are many younger fans who appreciate having a ninja protagonist of their own. And while the story may seem recycled, it's easier for newcomers to enter here than try to get into a series from a different time. While Boruto shares many of his father's younger characteristics, his background as a spoiled and beloved child, the son of a Hokage, mean that his growing pains are different than those experienced by his father, the outcast who bore the spirit of a fox demon. Not many series are able to follow their younger characters into adulthood and parenthood, which lends a little bit of realism to Naruto's ultimate quest and some gratification for fans who'd been rooting for the hard-working troublemaker from the start.