The Untold Truth Of The Dark Crystal

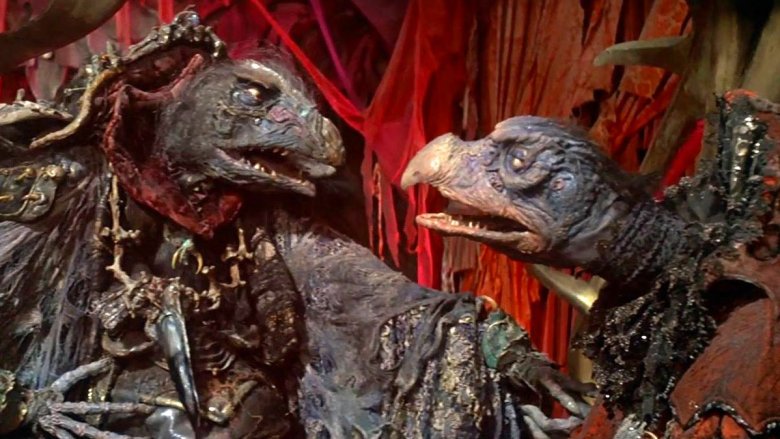

In 1982, Jim Henson showed the world than he was more than just "the Muppet Guy," responsible for the adorable and often hilarious puppets who populated The Muppet Show, Sesame Street, and other family-friendly products. That's the year Henson released The Dark Crystal, an ambitious, visually stunning achievement of fantasy, cinema, and puppetry. It's an epic tale set far away and long ago on the planet Thra, where a magical crystal cracks and splits, leading to two vying cultures: the Skeksis, who harness this "dark crystal" for its power, and the Mystics (or urRu), the magical good guys. Various other wondrous creatures called Gelflings, Fizzgig, Aughra, and Pod People play a role in this story for the ages, told entirely via lifelike objects created by Henson and company. After more than 30 years developing a growing, devoted fanbase, The Dark Crystal returned in 2019 in the form of the Netflix miniseries The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance. Here's a deep exploration of Henson's most magical and mysterious work — the untold truth of The Dark Crystal.

The Dark Crystal came from the Land of Gorch

Perhaps the only thing in Saturday Night Live history that's less popular than Sinead O'Connor tearing up a photo of the Pope is the 1975-'76 recurring feature "The Land of Gorch." Each week, viewers would check in with these fantastical and grotesque monster creations with names like Peuta, Scred, and Ploobis. Although stemming from the minds of Henson and company, the "Gorch" material lacked that signature Muppet magic. Because of Writers Guild rules, SNL writers had to write the "Gorch" bits, not Henson employees. Those staffers resented having to tackle what was essentially an outside project rather than write their own edgy comedy sketches, and after one year, all parties involved decided it would be best to end "The Land of Gorch."

While "Gorch" wound up an obscure footnote in SNL lore, it directly inspired one of Jim Henson's most triumphant works. In the '70s, Henson developed a deep appreciation for the work of fantasy illustrator Brian Froud, an English artist with an affinity for bringing exquisitely detailed trolls, ogres, elves, and fairies to the page. Around the time that Henson got into Froud's work, Froud was thinking about turning his creatures into a puppet-based film, and so he happily accepted a 1977 invite from Henson to visit the latter's workshop in Elstree, England. Once Froud saw the highly detailed "Land of Gorch" puppets, he knew Henson was the man to bring his illustrations to life, and the two creators agreed to make some kind of fantasy film together.

How a snowstorm begat The Dark Crystal

While Henson and Froud knew they wanted to make a fantastical puppet adventure together, it took some time to figure out just what kind of story they'd tell. In early 1978, the duo held a series of early-morning development meetings, focusing more on the idea, look, sensibility, and "world" of the film, leaving the plot structure for later. Henson decided to let Froud develop the film's imagery — characters and setting — while he came up with the notion that the film would take place in "a pantheistic world in which mountains sang to one another and forests were alive."

The bones of the story came together in February 1978 during what would prove to be a fortuitous blizzard. While waiting on a flight to London at JFK Airport in New York City, two feet of snow ground all planes. Henson and his 16-year-old daughter Cheryl checked in to an airport motel. That's where father and daughter worked out a plot, and even came up with a title: The Crystal. Henson would later merge into what became The Dark Crystal elements of an abandoned fantasy film treatment he'd written called Mithra, which included two warring populations, one magical, one wicked, that long ago split apart from one "mother" species.

The Dark Crystal's made-up languages weren't completely fake

The Dark Crystal is one of the first live-action narrative films with no visible humans in the cast. It's also one of the few — alongside '80s contemporaries such as Quest for Fire and Caveman — in which characters speak "fake" languages, which is to say ones invented by linguists specifically for the project.

"We did spend a great deal of time creating several non-English languages," The Dark Crystal producer Gary Kurtz told Starlog, adding that children's fantasy novel author Alan Garner "worked up some helpful suggestions for us based on some ancient languages." For example, a language built for use by the Skeksis was based on an offshoot of ancient Egyptian. The one used by the Pod People is a take on Serbo-Croatian, spoken in parts of the former Yugoslavia. "It's not an exact language that they speak, but people who are fluent in Polish, Russian, and other Eastern European languages, all say that they can recognize words," Kurtz said. Why not just invent a language from scratch? It's all for the sake of realism. "Certainly, it's much easier to make up nonsense sounds, but you can sense it it it doesn't have any basis in reality," Kurtz noted. "In a real language, there are certain repeatable phases and a structure which makes the sounds mean something."

Say what now?

The Dark Crystal held its first test screening in Washington, D.C., in March 1982. According to a memo sent to his staff (via Henson: The Biography), Henson thought it would be good to watch the film in order "to make final decisions regarding the editing of the film as well as the audio and the music." Tweaks, in other words — not a complete overhaul of the film's vibe and audacious approach, like how the Mystics and Skeksis spoke without English subtitles. Henson figured the plot would be made clear through the characters' actions and tone, but the test audience didn't think so, and neither did executives at the film's distributor, Universal, or at ACC, the production wing of Holmes a Court, the movie's financier. They thought they had an expensive flop on their hands, and that they'd spent $25 million on a baffling, impenetrable experimental film. Henson had no choice but to follow the directives of the people in charge, and agreed to dub the movie into English.

Screenwriter David Odell had to essentially compose a whole new script, with dialogue that not only told the story but matched up to the puppets' mouth movements. Then Henson had to hire a whole new cast of voice actors, then have editors sync their words with the finished visuals. In total, it took four months to make The Dark Crystal's audio track workable.

How Jim Henson took back The Dark Crystal

The Dark Crystal's financiers at corporate giant Holmes a Court didn't seem to like much about The Dark Crystal at all. According to Henson's diaries, reprinted in Henson: The Biography, the money-handlers thought the Mystics were "too boring" and suggested that Henson cut down their time onscreen and increase the presence of the Skeksis, because a test audience in Detroit responded favorably to them. Henson put them off, but when Holmes a Court, trying to ensure it made good on its hefty investment, wanted to send representatives to the editing bays to ensure that their changes were implemented, Henson cracked. Upon returning to his office headquarters in New York, he called his agent and informed him that he was going to buy ACC out of The Dark Crystal. If they weren't the money men anymore, they couldn't change a frame. Henson had about $15 million available at the time, almost all of that coming from royalties of licensed Muppet merchandise; Holmes a Court accepted the offer, and The Dark Crystal wholly became the property of Jim Henson. (The film went on to earn $41 million at the box office, so Henson turned a profit.)

The Dark Crystal Clothing Collection

Plenty of TV shows and movies get a merchandising campaign. Stocking stores with branded products both promotes a project and potentially earns a fortune for production companies. Stuff based on Muppet-based entertainment is a perennial source of revenue, and it was his cut of the Muppet merch windfall that allowed Jim Henson the funds to make The Dark Crystal the way he wanted to make it. But that movie was hard to market in this way — it's a dark fantasy suited more to older, literate audiences, as opposed to the toy-hungry kids who favored more mainstream Henson fare like Sesame Street and The Muppet Show. As a result, The Dark Crystal did feature some branded items available for purchase... but they were really weird and kind of expensive, too.

Following up Dark Crystal museum exhibits in Los Angeles and New York before the film's release, Jim Henson tasked the film's costume designers at his London workshop to develop the Dark Crystal Clothing Collection, a high-end haute couture series of clothes inspired by the film's fantastical, otherworldly creatures. It was already an idea with limited appeal, and only four pricey fashion boutiques landed the rights to sell the Dark Crystal Clothing Collection — including Henson's personal favorite shop, LIberty's of London.

The Dark Crystal sequel that never was

In creating a vast and elaborate fantasy world on par with the Westeros of Game of Thrones or the Middle-earth of The Lord of the Rings, Jim Henson and his collaborators developed a wealth of background stories and other ideas for The Dark Crystal. While many video games, comics, and books tell more stories of the Skeksis and such, a filmed follow-up to the 1982 flagship film in the franchise never materialized.

In 2006, The Jim Henson Company announced the beginning of production on Power of the Dark Crystal, a sequel set centuries after the first film, following a girl made of fire who teams up with a rogue Gelfling to swipe a shard of the Crystal to reignite a dying sun. Producer Lisa Henson told MTV that it was based on "the basic bones of the sequel" idea discussed two decades earlier by Jim Henson and Dark Crystal screenwriter David Odell. Samurai Jack and Dexter's Laboratory creator Genndy Taratakovsky signed on to direct the movie, which would have combined computer-generated animation with live-action animatronics. But alas, it wasn't meant to be. "We did visual designs, we did a script, we started testing things," Tartakovsky later told IndieWire. "We were always a couple of dollars short, and it just kind of fell apart."

Back to Thra, at long last

In August 2019, Netflix debuted one of the most hotly anticipated and long-awaited projects in recent memory: The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, a prequel miniseries to 1982's The Dark Crystal. The love of all things Muppet and the enduring cult appeal of The Dark Crystal led to a staggeringly stacked voice cast for the project, including Helena Bonham Carter, Mark Hamill, Lena Headey, Keegan-Michael Key, Andy Samberg, and Sigourney Weaver.

This is not a project that came together quickly. In 2011, Clash of the Titans director Louis Leterrier took some meetings with the Henson Company. As he told Vanity Fair, he watched The Dark Crystal on the set of Clash of the Titans constantly for inspiration, prompting the company to ask Leterrier to helm its Dark Crystal sequel project. He thought the script developed under Genndy Tartakovsy was "interesting" but didn't answer many of the questions raised by the original film; he was more excited about "What happened before: What led this civilization to be extinct? What is the story of this genocide — what happened?"

Henson executives agreed and changed Leterrier's sequel to a prequel and combined it with an animated series in development at cable channel the Hub, making it a miniseries instead of a movie. In 2014, the series landed an outlet. Former Hub executive Ted Biaselli joined Netflix, and when Henson approached him about The Dark Crystal series, everything finally came together. "There was never a maybe," Leterrier recalled. "It was, 'But of course.'"

Everything on the screen is real

Filmmaking technology has significantly progressed since the early 1980s, when Jim Henson made The Dark Crystal. The fact that the film was made in the pre-CGI stage makes its visuals all the more impressive — the entire elaborate fantasy world and its hundreds of characters were all real puppets, motors, and models filmed with in-camera effects. Director Louis Leterrier had a lot more tools at his disposal when making the Netflix prequel miniseries The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance. But Leterrier is such a superfan of the original film, and so committed to making a worthy and authentic follow-up, that he vowed to use as much practical effects as possible. "I love CGI, but we're not using CGI in this one," Leterrier said at the 2018 New York Comic Con (via SyFy). "Puppets, man. Puppets!" He was probably only semi-joking when he quipped that "Every puppeteer in England worked on our show," but was serious when he said that while some CGI technology was implemented, it was only to digitally remove puppeteers from footage of action-heavy scenes. But there's still a lot that can be accomplished with puppetry and without computers, and Leterrier was committed to pushing the boundaries. As he told SciFiNow, "In every scene at least I want to do something that has never been done with a puppet."