Things Real Fans Understood About It: Chapter Two That Critics Didn't

It: Chapter Two has finally hit the big screen, and while the epic conclusion to the adaptation of Stephen King's masterful 1986 novel It has largely left fans satisfied, a fair number of critics weren't so impressed. The flick has received an 80 percent audience score, not bad at all — but it currently stands at only 63 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, in contrast to the 86 percent scored by its predecessor, 2017's It: Chapter One.

We've seen the movie (and we really dug it), and we've also read the stacks of negative reviews, most of which take It: Chapter Two to task for its perceived padded run time, emphasis on humor over horror, and certain plot elements that some felt were changed for the worse from the way they were presented in the novel. Speaking of the novel, we've also read that (many times), and we're here to tell you that some of these reviewers — even ones who professed to have read and enjoyed the book themselves — didn't exactly hit their mark in their criticisms.

Of course, many of these opinions are subjective; for example, if one is of the opinion that It: Chapter Two simply wasn't scary enough, well, one is entitled to that opinion (although we have a suspicion that one may have taken several bathroom breaks at all the wrong times). But a few of the pervasive criticisms of the flick can be objectively shot down, and guess what? We're about to do that.

Spoilers for It: Chapter Two follow.

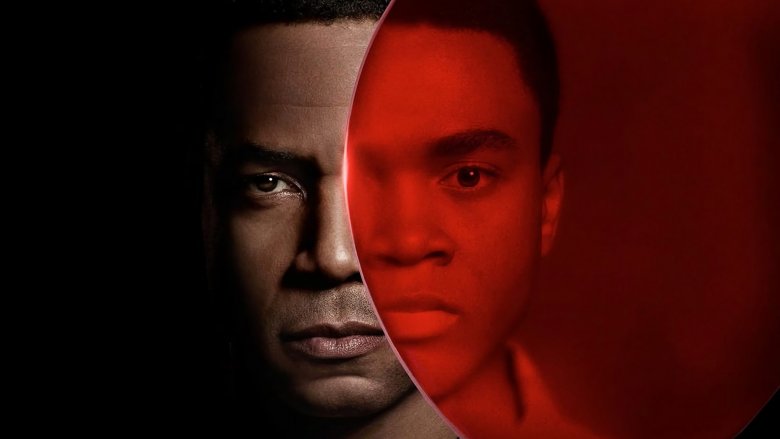

How It: Chapter Two changed Mike's story

Several changes were made to the character of Derry's town librarian Mike Hanlon, and the criticisms around these changes are confusing (and sometimes contradictory). All of the Losers are bullied, but in King's novel, the bullying of Mike by Henry Bowers was particularly awful due to Bowers' unrestrained racism. Some observers took issue with the fact that, in both movies, the racist element of Mike's bullying was substantially toned down — leveling charges of squeamishness on the part of director Andy Muschietti and screenwriter Gary Dauberman.

In our opinion, this is incorrect. For one, the racist nature of the Bowers gang's bullying is certainly implied, even if no racial slurs are hurled at the young Mike (and really, did anyone need that?). For another, the films were set roughly 30 years later than the novel, with the time period of It: Chapter One transposed from 1958 to 1989. We all know that racism is alive and well even today, but to say that overt racism was more likely to be encountered in the '50s than the '80s is not a stretch. We submit that neither film suffered from the filmmakers' decision to make the racial aspect of Bowers' antagonism toward Mike more subtle, and that the decision was the obvious byproduct not only of the time period switch, but of adapting a 33-year old novel.

The fate of Mike's parents in It: Chapter Two

Another difference between literary Mike and cinematic Mike: the fate of his parents. While they were implied to have died uneventful deaths in the novel, they were incorporated into Mike's tragic backstory in the movies, having burned to death inside a locked apartment while young Mike looked helplessly on. A newspaper headline conspicuously featured in It: Chapter Two refers to a pair of "crackheads" who set themselves on fire in front of their young son — but this is later revealed to be one of Pennywise's tricks. After the malevolent entity is defeated, the true headline is revealed, and it's made clear that Mike's parents actually died in an electrical fire. (We might have been clued in by the fact that no actual newspaper would use the word "crackheads.")

The reason for this change is fairly obvious: Mike isn't as much of an outcast due to his race in the films as he is in the novel, and for narrative reasons, the poor kid needed a good dose of trauma (which we'll get to shortly). But one spectacularly wrongheaded review by Slate's Jack Hamilton opined that the change smacked of actual racism. "To transform the only black protagonist from the child of responsible, nurturing parents into the child of negligent crack cocaine addicts is far worse than lazy writing; it's to actively draw from a deeply racist set of cultural tropes," he wrote; we guess he must have been yawning really wide or looking at his watch when the true newspaper headline was revealed.

Critics didn't understand It: Chapter Two's runtime

Of all the critical gripes leveled at It: Chapter Two,by far the most common had to do with the film's admittedly gargantuan run time. The film was labeled "arduous," a movie that "takes an incredibly long time to get to the point," with its "muddled and meandering" narrative. Here, we'd like to gently point out that King's novel is over 1,100 pages long, and that an unbelievable amount of material was left out in bringing the story to the screen. Much of this material was given shout-outs in the form of slight tweaks to the films' story, such as the fire that killed Mike's parents — which was a clear reference to the novel's fire at the Black Spot, a historical event which was used to illustrate Pennywise's centuries-long influence on Derry, and which was given an entire chapter in the book.

Those going into It: Chapter Two expecting a brisk, breezily plotted ride to the final showdown either weren't familiar with the source material, or were expecting Dauberman and Muschietti to take far more liberties with it than they did. Sure, the flick takes awhile to get to the climax — but the individual and collective journeys of the Losers' Club play directly into how they deal with the horror of that final confrontation, and if they had been given short shrift, it's likely that many of these same critics would have been complaining about that.

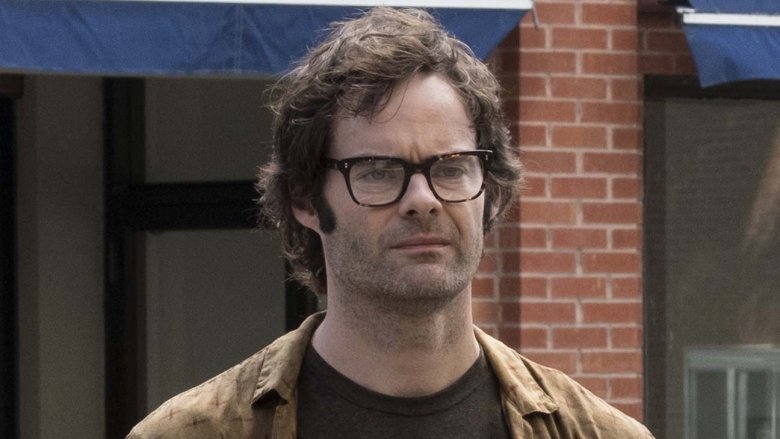

Fans better understood the comic relief in It: Chapter Two

Many of It: Chapter Two's critical notices also took issue with its liberal use of humor, and in particular the wisecracks which the adult Losers' Club are prone to lobbing at each other as they prepare to face off against a horror so unimaginable that just the thought of returning to Derry was enough to make one of their number commit suicide. Much of the humor is even intertwined with the horror, as with a brilliant visual homage to John Carpenter's 1982 classic The Thing that prompts Bill Hader's Richie Tozier to expertly deliver an iconic, hilarious (and unprintable) line from that movie.

In our estimation, what these critics fail to understand is that the humor is there to mask the fear. It's the old "whistling past the graveyard" trope; one laughs so that they may not cry, or, you know, soil themselves out of sheer terror. The Losers' Club are an irreverent bunch in both the novel and the films, and their banter doesn't just have the effect of entertaining the audience, but of keeping them from literally going insane. If anything, their humor is dialed down from the book — and if you haven't read it, allow us to make plain that in the bibliography of Stephen King, which is full of some of the most terrifying fiction ever written, It might very well be the scariest selection of them all.

Some critics didn't get that It: Chapter Two is about repressed childhood trauma

Perhaps the most frustrating reviews of It: Chapter Two were those that completely whiffed in pinpointing the film's underlying themes. Take, for example, this excerpt from the review of NBC News' Noah Berlatsky: "Chapter Two presents itself as an exploration of nostalgia and memory. The adults magically forget their childhood adventures when they move away from Derry, and the movie is about them reacquainting themselves with their past friendships and with their true selves upon their return." That, dear reader, is a big, fat nope.

What the Losers are reacquainting themselves with, voluntarily or not, are the horrors of their youth — the searing, inescapable trauma which many of us deal with, and which is often buried not by some magic, but as a form of emotional self-defense. Don't take our word for it: Dauberman spelled it out in an interview with Inverse. "I think as an adult, we all have some repressed trauma somewhere in us," the scribe said. "I'm the same age as the Losers in [It: Chapter Two]. I followed up on my own childhood, and how easy it is for memories to fade. Even the more traumatic ones. Like getting details wrong, or [asking], 'Did that happen? When? I can't remember.'"

Of course, many of our childhood traumas have to with our own peers — those bullies who exploit our weaknesses in an effort to lessen their own. Such bullying is a recurring theme in It — and for a good reason.

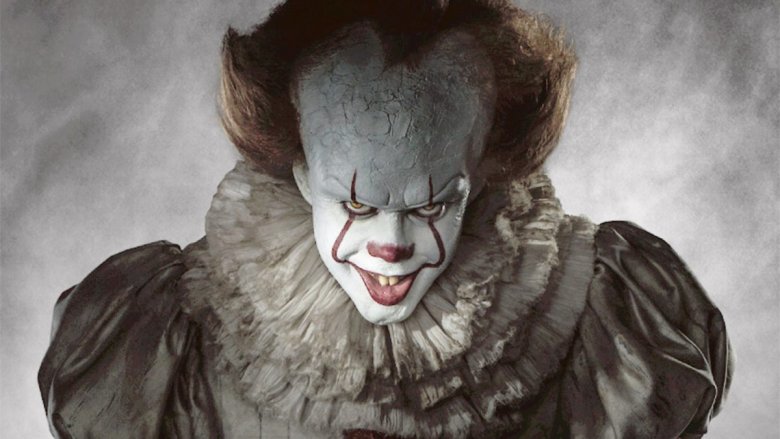

It fans know who's the biggest bully of all

The ending of King's novel, esoteric as it is, is practically unfilmable. The filmmakers behind It: Chapter Two offered up their own interpretation, and of course, many critics jumped all over it: as a gargantuan, monstrous Pennywise menaces them, the Losers essentially take away his power by ridiculing him, knocking him down peg after peg, until he's physically small enough that they can rip out and destroy his still-beating heart.

At least one observer came somewhat close to the mark by opining that the Losers "sort of bully [Pennywise] to death" during a conversation with Muschietti, only for the director to set him straight: "I didn't see it as bullying so much as it was about reversing the power of belief on this creature, who uses belief as a weapon to kill his victims... For the first time, it's the Losers who have this power, and they start telling him what he is... You're a headless boy; you're a weak old woman. And finally they converge on the concept of a clown, which is just the most helpless and powerless thing... The power of belief is Pennywise's power, but it's also his biggest weakness."

So it is with all bullies, whose victims must feel weak in order for them to feel powerful. Pennywise is simply the biggest bully of all — and like all bullies, once that "power of belief" was taken away, he had nothing left.