The 5 Biggest Lord Of The Rings Mysteries, Ranked (And Solved?)

One of the most endearing things about Middle-earth is the unexplored size and mystery of the world that J.R.R. Tolkien created. The author himself clearly didn't have everything worked out and was constantly tweaking and adjusting things. When Peter Jackson adapted "The Lord of the Rings" into his monumental trilogy in 2001, the necessary process of adjusting, reworking, and cutting down Tolkien's source material led to even more inconsistencies.

Some of these have been discussed to death. For instance, we know enough about why the Eagles didn't take the Ring to Mordor. (Yeah, easy answer. Besides, to quote the author, "Shut up!") The history of Smaug's winged lizards is also largely unexplored, but Tolkien told us enough about what happened to the dragons to avoid it falling on a top mysteries list. It's also not worth revisiting endless enigmas like Tom Bombadil because, well, everything about him is a mystery, and it's pretty much unsolvable by design. (Tolkien did at least tell us he wasn't God, though.)

Instead, let's look at some truly challenging conundrums (specifically from the movies) and what Tolkien's texts have to say on the matter. We've ranked (and we've done our best to solve) each one below, ordered from tough to toughest. Enjoy!

Where are the other palantíri?

The seeing stones of Númenor (also called the palantíri) feature throughout "The Lord of the Rings" films. Saruman (Christopher Lee) famously has one with which he communes with Sauron. Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) also uses that stone to challenge the Dark Lord. When Gandalf (Ian McKellen) first sees that glowing orb in "The Fellowship of the Ring," though, he admonishes Saruman for using it, telling him that the lost seeing stones aren't all accounted for.

Okay. So where are they, then? Let's start with a number. J.R.R. Tolkien says there are seven official Palantiri or Seeing Stones in circulation. These are set up around the mainland of Middle-earth later in the Second Age and then become scattered and lost during the ongoing wars with Sauron. Of these, by the time of "The Lord of the Rings," Saruman has one (which Aragorn eventually keeps to help him watch over his realm), Sauron has another (that's how he talks to Saruman), and Denethor has a third (which contributes to him losing his mind). So that's three.

Another stone is originally kept in the capital of Gondor, Osgiliath. That is the ruined city in sight of Minas Tirith in "The Return of the King," and it's believed that one of the stones lies in the watery depths of the river that runs through the burned and broken area. The appendices to "The Return of the King" add that two other stones are lost in a shipwreck earlier in the Third Age. And the last one? It was called Elendil's Stone, and the appendices add that it was unique in that it only looked westward. It remained in an Elven tower near the Shire until the Elves took it over the sea with them after "The Lord of the Rings," which, considering the fact that they were going that way anyway, seems like a bit of a jerky move when they could have left it behind for others to use gaze at the Undying Lands over the seas.

Where are the Entwives?

Treebeard mentions the Entwives in the lengthy extended editions of "The Lord of the Rings." While we find out that the female half of his race is missing and the Ents don't know where to find them, though, we don't get a resolution to the question. Where are the Entwives? Unlike the palantíri, this time, the question is genuinely unanswerable.

In a letter in 1954, J.R.R. Tolkien explained, "I think that in fact the Entwives had disappeared for good, being destroyed with their gardens in the War of the Last Alliance [...] when Sauron pursued a scorched earth policy and burned their land against the advance of the Allies down the Anduin." In other words, the Entwives were probably wiped out in the lengthy war that culminated with the One Ring being cut from Sauron's hand (at the beginning of "The Fellowship of the Ring" movie).

In that same letter, the author does offer a glimmer of hope, saying, "Some, of course, may have fled east, or even have become enslaved: tyrants even in such tales must have an economic and agricultural background to their soldiers and metal-workers. If any survived so, they would indeed be far estranged from the Ents." He finished the sobering thought by saying that, just possibly, this experience may have aligned the two halves of the arboreal race a bit more through a shared anarchical mindset, which could have made them more compatible. (They initially split up due to incompatibility in interests, with the wild Ents failing to align their lifestyle with the originally orderly Entwives.) His final words on the subject are, "I hope so. I don't know." — which is about as much of the mystery as we can hope to solve.

How does the One Ring work (and why does it exist in the first place)?

What is the One Ring? Sure, it's a Ring of Power. Yes, everyone wants it. But what does it do exactly? Why did Sauron even make it if all it takes is tossing it into a volcano to completely destroy his power? Seems like a weird weakness, right? Fortunately, Prime Video's "The Rings of Power" series is helping to answer the question of the motivation behind Sauron's forging those titular trinkets. But what about how the One Ring works?

It turns you invisible, sure, but that's more of a side effect than a feature. The real power of the Ruling Ring is its (largely undefined) ability to help its wearer dominate other individuals' minds and wills. The question of what the One Ring does and how it works is as mysterious as it gets, and in a certain sense, this one is a case of too many varying and inconsistent pieces of information making the question too hard to answer.

Bilbo, for instance, uses the One Ring casually in the books and doesn't seem the worse for the wear most of the time. Frodo (Elijah Wood) wears it in "The Lord of the Rings," and the world around him looks unclear, foggy, and distressed. But he can see spiritual beings, like the Nazgûl and Sauron clearly. In "The Fellowship of the Ring" book, Frodo is also able to see a powerful Elven lord named Glorfindel as a white light "on the other side" — i.e. his spirit rather than his physical form.

As far as function, along with invisibility, the Ring allows Samwise to understand Orcs speaking in another language in the books. Beyond these utilitarian manifestations, though, the Ring is cryptically designed as an outward form of Sauron's potency. It is an expression of and tool for his domination of others to his will, something that occurs in a non-tangible manner and naturally comes with some risks (like losing it and having it destroyed behind your back).

The best answer we have here comes from J.R.R. Tolkien himself. In a letter to a fan in 1958, he described the Ring, saying, "You cannot press the One Ring too hard, for it is of course a mythical feature, even though the world of the tales is conceived in more or less historical terms." So, in Tolkien's own wording, the operative element of the ring is a mythological activity, even in the midst of cold, hard historical Middle-earth storytelling.

What is up with the half-elven stuff?

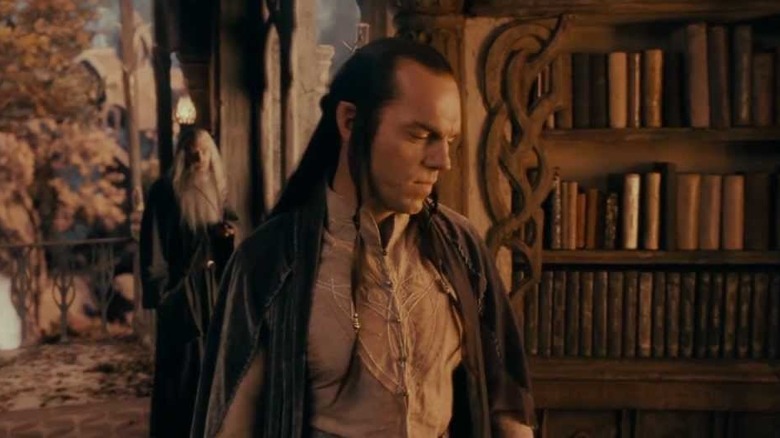

Elrond is called Peredhel or "half-elven." Arwen is thousands of years old — and yet, she chooses a mortal life. What is up with these half-mortal, half-immortal folk? The answer lies in a complicated mess of ancestral connections that J.R.R. Tolkien traces clearly back to the First Age of Middle-earth history, several thousand years before "The Lord of the Rings." In that age, there are a few unique pairings of Elves and Men, starting with two major connection points.

The first is between the man Beren and the lady Lúthien, who, herself, is half Elf and half Maiar (basically an angel). The other pairing is between the man Tuor and the she-elf Idril. The descendants of these unions eventually lead to a smorgasbord of famous folk, including the iconic First Age hero Ëarendil, Elrond, his brother Elros (who founds Aragorn's family tree), Elendil, Isildur, Aragorn, and Arwen. But where does the choice between mortality and immortality come into the picture?

The answer can be found in "The Silmarillion." When Ëarendil and his wife, Elwing, face the Valar (the angelic guardians of Middle-earth), their fate is decided. The chief Valar, Manwë, declares, "And this is my decree concerning them: to Eärendil and to Elwing, and to their sons, shall be given leave each to choose freely to which kindred their fates shall be joined, and under which kindred they shall be judged." Those children are Elrond (who chooses immortality) and Elros (who chooses mortality). After that, though, things get murky again. Elros' descendants, for instance, can't avoid mortality after their patriarch's decision. In contrast, Elrond's children can lay down their immortality even after living thousands of years. It feels like an area that J.R.R. Tolkien never fully fleshed out, but at least we have the basic explanation to go on.

Who are the Nazgûl?

The Ringwraiths, or Nazgûl, are the nine feared servants of Sauron. They are enslaved to his will and spread his terror across Middle-earth throughout the "Lord of the Rings" story. But where do they come from? Who are they? We know they are mortal Men who each have a Ring of Power, but which mortal Men are they?

This one is tricky and only partially answerable. Let's start with the most obvious bit: Khamûl. The book "Unfinished Tales" gives us the only named Nazgûl, calling him "Khamûl, the Shadow of the East." Khamûl is also called the Black Easterling and is second in command to the other semi-named Ringwraith: the Witch-king of Angmar. The latter is the terrifying fella that Éowyn strikes down on the fields of the Pelennor in "The Return of the King."

After that, we don't get any more names for the other seven. But we do get a few more tidbits and hints. "The Silmarillion" states, "Among those whom [Sauron] ensnared with the Nine Rings three were great lords of Númenórean race." Later in that book, it adds, "Men proved easier to ensnare. Those who used the Nine Rings became mighty in their day, kings, sorcerers, and warriors of old." While that second quote technically applies to what happened afterward, it does help us profile the Nine a bit more. Both before and after they receive their rings, most of them appear to be individuals who already are or are prone to become rulers, warriors, and magic-wielders. But as far as specific identities go, we're left with just a scrap of information about Khamûl and the rest remains a mystery.