The Untold Truth Of Frankenstein

When someone brings up Frankenstein, just about everyone has the same mental image: a hulking, gray-green leviathan of an undead man, probably with stitched-together body parts and bolts in his neck. He moans and groans and walks stiffly, with his arms outstretched before him. But this is not the image put forth in Mary Shelley's original novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Modern viewers of Frankenstein-inspired media have nearly a century's worth of film, television, and other media adaptations to thank for the pop culture phenomenon known as the modern Frankenstein. Each version varies, some sticking close to Shelley's original intention of a pitiable creature not meant to walk the Earth, some going for the shock and scare value of the terrifying undead killer. But all of them combined — stitched together like the parts of a dead man brought to life — have created not a monster, but a landmark of horror entertainment.

How did this happen? Here's the story of Frankenstein's long journey from foundational sci-fi novel to pop culture icon.

"It's alive!"

Everyone knows that when Dr. Frankenstein lowers the monster's slab down from the lightning and sees the creature start to move, he shouts, "It's alive!" It's a sound clip that has played over and over in countless films, been sampled in music, and even referenced in the 1968 horror film Rosemary's Baby. But in the book, which reads as a personal confessional from the man himself, Victor Frankenstein never once utters this phrase.

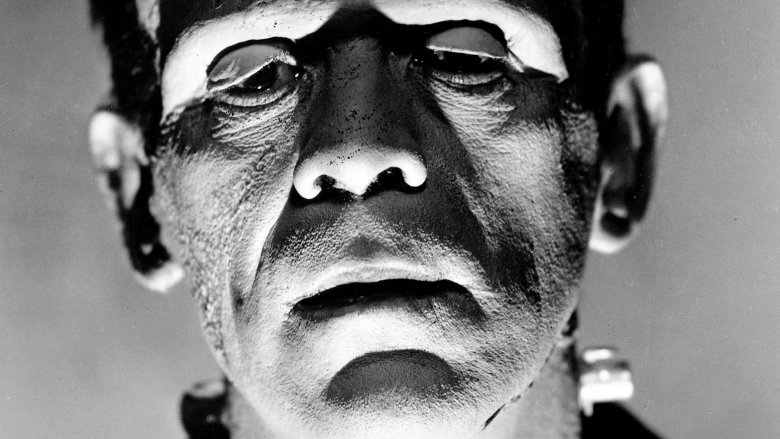

Its origin lies with James Whale's 1931 Universal Frankenstein film starring the famous (and infamous) Boris Karloff, where Frankenstein's first name is even changed to "Henry," instead of the harsher-sounding Victor. While the film does portray the monster as a sympathetic character, it breaks hugely from Shelley's original novel. Even in 1931, many film-going audiences would not have been intimately familiar with the 1818 proto-science fiction/horror story. The filmmakers took advantage of the ability to break away from its constraints to create something different but ultimately groundbreaking in the world of horror cinema.

It's (not) electric!

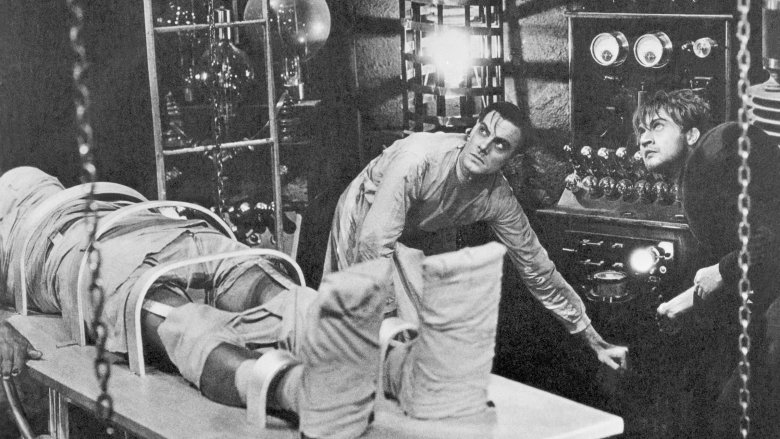

Another aspect in which the 1931 Frankenstein film diverges from the original novel is in the use of electricity to reanimate the monster. Though Frankenstein in the novel does claim to "infuse a spark of being" into the man he has stitched together, the methods through which he achieves this goal remain a mystery. Shelley seems to have been less concerned with how the monster came to be than with conveying the terrifying notion that a mortal man was able to create life from nothing.

Of course, movies are a visual medium, and audiences expect to see the monster come to life. Some speculation can be made that Universal chose to use electricity based on the understanding, discovered approximately 200 years prior by Italian doctor Luigi Galvani, that dead tissue can be provoked to move with the application of electricity. Obviously, no one has actually been able to bring someone back from the dead, but it makes a certain amount of sense that it would take something shocking to jump-start the human heart into pumping once again. Besides, lightning storms are dramatic, and drama is really what you want in a horror flick.

Frankenstein's silent creature

Even though Boris Karloff's rendition of Frankenstein's monster is the oldest one most people remember, it was not the first film version of the creature. There were a few Frankenstein adaptations made during the era of silent film, following years of stage adaptations. The first movie version in 1910 came from Edison Pictures and, like most films of that time period, was relatively short and took many liberties with the story. Most surprising to modern viewers is the appearance of the monster, with over-the-top makeup and long, wild hair. It's in keeping with theatrical traditions from which film had yet to break away, but it's also fairly faithful to Shelley's novel, in which the monster is described as having "hair of a lustrous black, and flowing."

Boris Karloff, then, was certainly a departure in appearance to Shelley's original monster. There would be a couple more Frankenstein silents: Life Without Soul in 1915, and the Italian Il monstro di Frankenstein (The Monster of Frankenstein) in 1921. Unfortunately, there are no surviving copies of either of these later silent films, so lovers of truly old cinema must content themselves with the 1910 version.

"Well... we warned you!"

Though its Gothic charms and moody atmosphere definitely hold up, modern viewers will likely not find 1931's Frankenstein to be particularly scary, especially compared with modern horror media. But during the Depression, film was still relatively new, and its limits were still unknowable. Audiences had not been treated to visions of monsters quite as scary as Frankenstein's — except for Bela Lugosi's Dracula earlier that same year. But because Frankenstein was so potentially shocking to audiences of the time, the filmmakers chose to do something they hadn't needed to with its vampiric predecessor.

The film opened with actor Edward Van Sloan walking out from behind a curtain to issue a word of warning to audiences on behalf of Universal Pictures producer Carl Laemmle that the film they were about to see might just horrify them. In an age where we do everything we can to extend our lives, the idea of coming back from the dead is perhaps not as terrifying, and the thought of "playing God" is less of a moral panic than it would have been in a more church-going era. But for so many, Frankenstein offered their first true taste of Hollywood terror, and audiences devoured it. Of course, it didn't hurt that the "warning" actually served to cleverly heighten the tension about what they were going to see.

Karloff the Uncanny

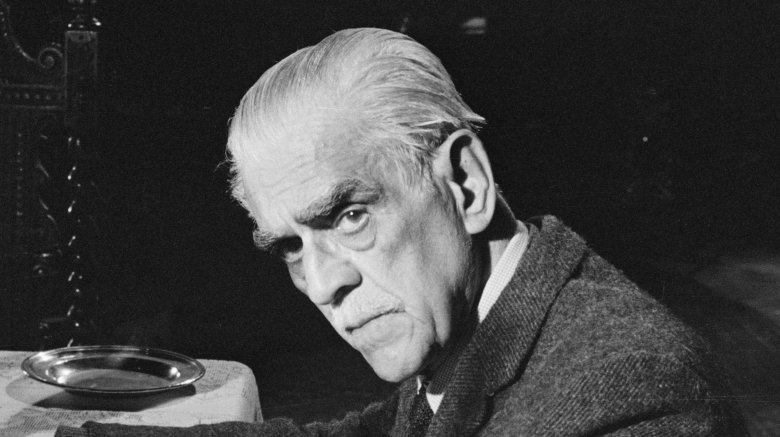

Before Frankenstein, Boris Karloff was not a well-known actor. Born in England and with a mixed English-Indian heritage, Karloff had chiefly acted in theater up until the '20s, when he took small roles in many films. When he landed the role as Frankenstein's monster — completely coated in makeup, propped up on risers in his boots, and his face sunken from the removal of his oral bridgework — he was nigh unrecognizable as a human actor. He had transformed into a great hulking beast of a man, and in order to preserve the mystery surrounding him, Universal producers opted to credit him in the opening titles simply with a question mark (the repeated cast list at the end does reveal his name).

By the 1935 release of the sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, he was already iconic, and would be credited, diva-style, by the single name "Karloff." He's now one of the best-known figures in horror film history, but he spent a lot of time in those early Hollywood years appearing in bit parts and as problematic yellowface characters until finally he was saved by the monster. He was also instrumental in the formation of the industry's first (and still active) union, the Screen Actors Guild — a passion inspired by the often unsafe working conditions on Frankenstein.

Bela Lugosi's tenure as Frankenstein's monster

The success of Dracula isn't the only way in which that film contributed to Frankenstein. Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi, so entrancing in his role as pop culture's most famous vampire, was originally considered for the part of Frankenstein's monster. Ultimately, he chose to turn that role down, thus paving the way for Karloff to take up the neck bolts. But because Lugosi was best known for playing monsters, he had a second chance at playing the monster again, opposite Lon Chaney, Jr., in 1943's Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man.

Chaney had played Frankenstein's monster in The Ghost of Frankenstein in 1942 (in which Lugosi played Ygor), and the Wolf Man in the 1941 film of the same name. Obviously incapable of playing both roles, especially considering that each required tons of makeup and prep time to achieve visually, Lugosi was brought in to fill the oversized shoes of the reanimated man. Chaney would continue to play both Frankenstein's monster and the Wolf Man for years to come, but Lugosi would step away from the role and into more sinister parts that suited his style.

Stiff arms, warm heart

Just because Lugosi didn't have a long stint as Frankenstein's monster doesn't mean he didn't have a memorable one. If someone walks around stiffly, their arms thrust out before them, they are instantly recognizable as "playing Frankenstein." And they have Lugosi, not Karloff, to thank for that iconic stiff-armed salute.

Another visual aspect that so many modern monster lovers take for granted is once again proven not only to be an invention of film and not the original novel, coming about in 1943, about 125 years after Shelley first published her book. In said book, Frankenstein's ungodly creature is cited as being superhuman in his movement and abilities, a far cry from how we picture the living dead today. It is hard to know what is scarier — the large, swift wild man of literature, or the shambling, stiff-limbed corpse of film that reminds us all of our imminent fate.

Hammer Horror and The Curse of Frankenstein

Audiences loved horror in the '30s, but enthusiasm generally waned during the Second World War. In the late '50s, British studio Hammer Film Productions decided to take a shot at monsters and produced The Curse of Frankenstein. With this film, they launched their Hammer Horror brand and offered a color film from their studio for the first time ever. Since that fateful 1957 release, they have been known for their horror, producing several Frankenstein derivatives and sequels, along with many Dracula and Mummy adventures.

Acting legend Christopher Lee quickly became the star of Hammer Horror, playing Dracula a number of times, but only after initially playing Frankenstein's monster in The Curse of Frankenstein. It is interesting to note that such well-rounded British actors as Lee and Karloff really hit their film stride starting with the non-speaking part of an undead wretch. They are both now beloved and revered men in film history, owing everything to studios taking a chance both on them and on a 19th century novel with ever-relevant themes.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

All these films of Hollywood past tend to take great liberties with Shelley's novel, utilizing her main themes but embellishing or omitting as need be. In the early '90s, much like in the early '30s, the success of an adaptation of Dracula, this one directed by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Gary Oldman, Keanu Reeves, and Winona Ryder, inspired a follow-up Frankenstein adaptation. Produced but not directed by Coppola, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein hews more closely to the original novel than its celluloid ancestors.

Like Bram Stoker's Dracula before it, this Frankenstein boasts a surprising all-star cast including Kenneth Branaugh (who also directed) as Dr. Frankenstein, Helena Bonham Carter as fiancee/adopted sister Elizabeth, John Cleese in a rare dramatic role as Professor Waldman, a tutor of Frankenstein's, and — perhaps most shockingly — the handsome Robert De Niro at his peak as the creature himself. Unfortunately, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein did not quite have the pop culture staying power that Bram Stoker's Dracula had, but it is still lauded as the most faithful film adaptation of the original novel thus far.

Guillermo del Toro wants to make a monster

Horror fans everywhere can rejoice at the rumor that visionary filmmaker Guillermo del Toro is dead set on doing his own adaptation of Frankenstein for modern audiences. He notes that no adaptation has really utilized the novel as it is, and it would be interesting to see how he chooses to stage his own offering. Of course, the director has a history of dream projects that never get off the ground, so don't take his desire to make Frankenstein as an invitation to buy your ticket.

It's no secret that Del Toro loves monster cinema of the past. His recent Creature From the Black Lagoon homage, The Shape of Water, is a veritable love letter to Hollywood's horror history, complete with a romanticism that many modern horror films lack. His distinct use of aesthetics and encyclopedic understanding of cinema make Del Toro a perfect director for films that are nostalgic and sentimental, while also reminding us that there are horrors in this world worse than the monsters who haunt our dreams. It seems there was never any doubt in his mind that Dr. Frankenstein has always been the real monster, just as humanity remains the villain time and again in Del Toro's films.

Frankenstein, TV star

Before the dawn of television, Frankenstein's abominable creation had already conquered literature, the stage, and the box office — it was only a matter of time before he stormed the small screen. There have been hundreds and hundreds of references and homages to the monster in countless forms, and television is no stranger to this strange man. Even when they aren't direct adaptations, Mary Shelley casts a shadow every time cult favorites like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and The X-Files play with the concept of reanimated lifeforms.

In the second season episode of Buffy titled "Some Assembly Required," Buffy and the "Scoobies" discover that someone is killing young women to harvest their body parts in a Bride of Frankenstein-esque attempt to make a mate for an already reanimated young man. A couple seasons later, Buffy has to contend with Adam, a man frighteningly cobbled together with various parts of vampires, demons, and technology, his name a reference to how Mary Shelley referred to Frankenstein's monster outside of the novel.

In The X-Files episode winkingly titled "The Post-Modern Prometheus," agents Mulder and Scully find themselves embroiled in the strange case of a woman twice impregnated by a mysterious creature created in a lab. These are only a few examples of countless to be found in television, proving that Frankenstein's monster has been shuffling his way into our hearts for centuries.

It was a graveyard smash

Frankenstein and his monster, with their origins in the formative literature of the 19th century, have infiltrated film, television, toys, sugary breakfast cereals and, yes, even music. It's hard to make it through October without someone, somewhere playing those familiar first strains of the most famous Halloween song: "I was working in the lab late one night..."

"The Monster Mash," performed by Bobby Pickett (who borrows the name "Boris" for his musical jaunt into haunting) paints a picture of a cozy home life shared between mad scientist, unsightly assistant, and ungodly reanimated monster who creates a new dance craze. But it isn't the sole use of Frankenstein in musical tradition. The upbeat, kind of corny Halloween party songs of the '50s and '60s gave way to the showy offerings of metal legends like Alice Cooper, who recorded "Teenage Frankenstein" and "Feed My Frankenstein" (featured in the movie Wayne's World) in the '80s and '90s, respectively.

Cooper leaned into the monster aesthetic, paving the way for countless rock musicians to embrace the B-movie beauty of the horrorshow. Metallica (who frequently use literary, folkloric, and all-around spooky themes for their music) recorded "Some Kind of Monster," which frontman James Hetfield allegedly described as a song about a Frankenstein creature. As the final lyric says, this monster lives.